|

|

|

|

|

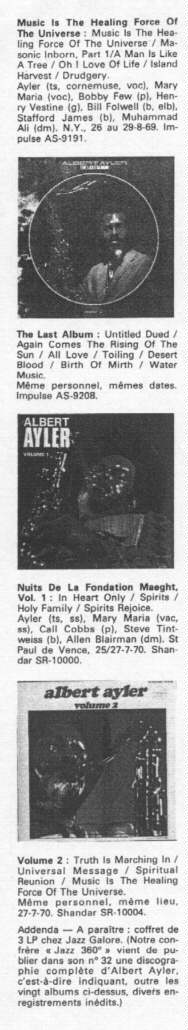

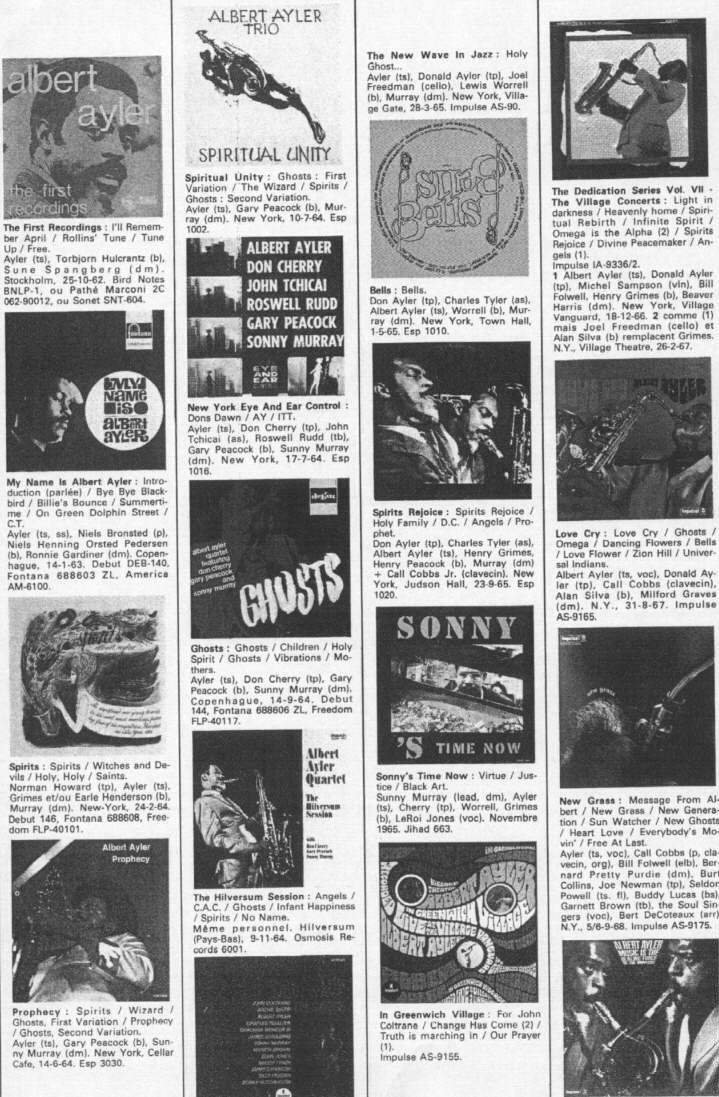

Articles 9 (1980-1989)

|

|

|

|

|

|

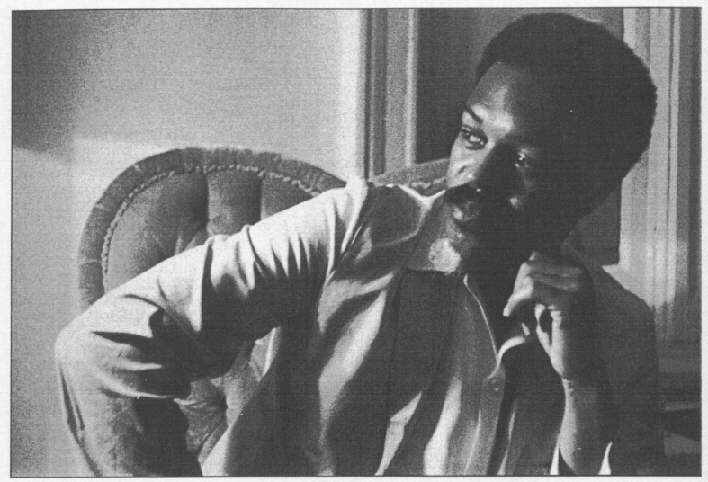

L’Enfer d’Ayler by Valerie Wilmer, translated by Christian Gauffre Jazz Magazine, December 1980, pp. 22-29 - France

Swing low on high: Albert Ayler resurrected by Bob Blumenthal The Boston Phoenix, 11 January 1983 - USA

. . Truth Is Marching In by Bill Smith and Brian Case The Wire, No. 3, March 1983 - UK

Untitled response to ‘.. Truth Is Marching In’ by Mike Hames The Wire, No. 6, March 1984, pp. 27-28 - UK

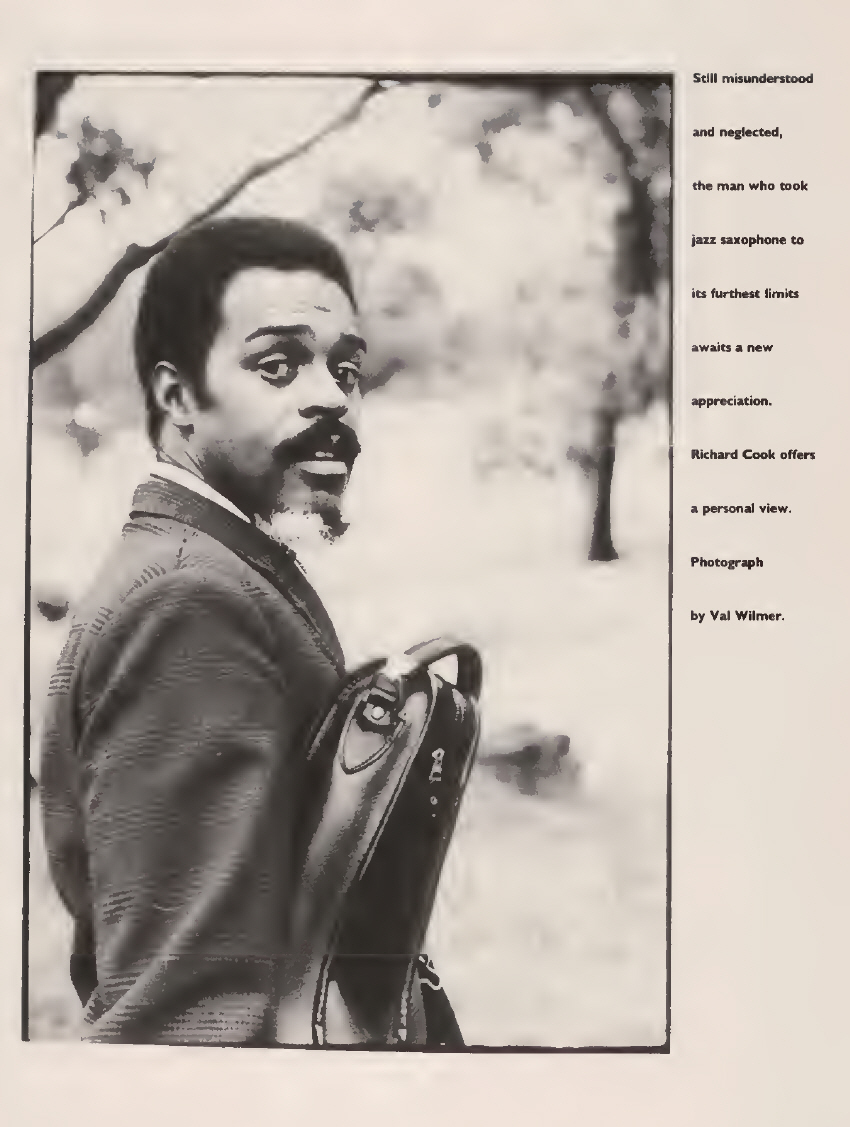

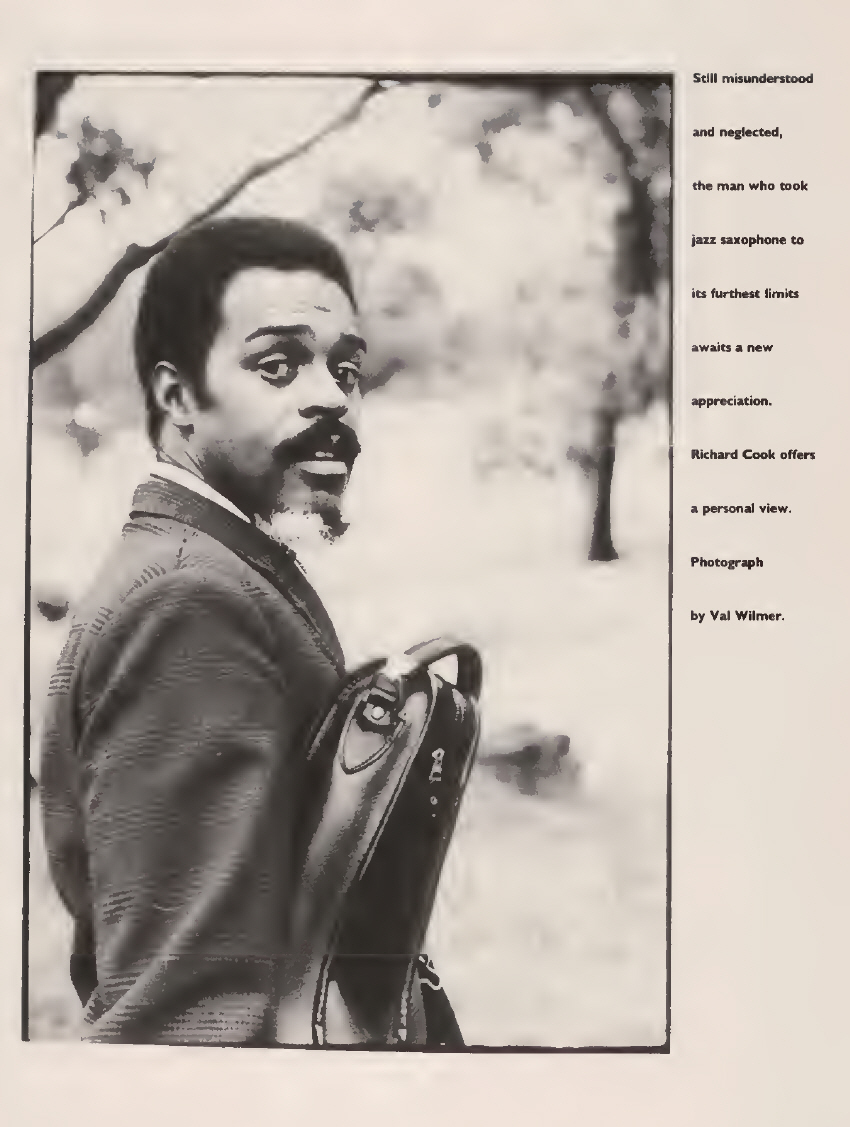

My Name is Albert Ayler by Richard Cook The Wire, No. 58/59, January 1989, pp. 60-63 - UK

*

Jazz Magazine (December 1980, p. 22-29) - France

L’ENFER D’AYLER

Alors que la plupart des grands disparus de l'histoire du jazz sont, à force d'articles et de rééditions phonographiques, honorés à la façon de monuments que l'on visite, le saxophoniste Albert Ayler, mort il y a tout juste dix ans, semble être encore tenu à l'écart. Comme si sa musique continuait de gêner et devait être interdite au public...

|

|

|

|

«Mon cœur était ailleurs. J’avais rencontré Albert Ayler quelque temps auparavant et c’était le seul musicien avec qui j’avais encore vraiment envie de jouer.» (Gary Peacock, Jazzmag 114, janvier 65.)

|

|

|

«Pourquoi diable ce Bells juxtapose-t- il ainsi les plus excessives audaces instrumentales et les plus plates expositions d’un thème? Tout se passe en fait comme si ces deux termes fondamentaux du jazz: le thème (exposé, reprise et variations) et l’improvisation, au lieu d’être, comme il est coutume depuis toujours, liés, enchainés, mêlés l’un à l’autre, se trouvaient ici radicalement séparés, comme deux éléments incompatibles, de densités différentes, qu’une centrifugeuse aurait radicalement dissociés, l’improvisation, matière souple et fluide, restant en suspension à la surface, tandis que le thème, chose pesante et grossière, constitue le dépôt. (...) Cette dissociation, assez éloignée du n’importe quoi, propose une nouvelle formulation du jazz: en voilà assez pour assurer l’apport de ce disque. Il faut d’autre part ne pas oublier que les révolutionnaires sont d’abord des naïfs, et que toute invention a, à un moment ou à un autre, la couleur du ridicule.» (P. CarIes et Jean-Louis Comolli, no 122.)

|

|

|

|

|

Lorsqu’on repêcha le corps d’Albert Ayler dans l’East River, le matin du 25 novembre 1970 au pied de la jetée de Congress Street, à Brooklyn, le monde de la musique venait de perdre un iconoclaste et la culture noire avait gagné un nouveau martyr (...). Albert Ayler était le dernier innovateur d’une lignée remontant audelà de Buddy Bolden, il fut aussi l’un des plus calomniés. En 1966, au sommet de sa notoriété, il fit une tournée en Europe et enregistra une émission pour la télévision britannique. La B.b.c. fut horrifiée. Les responsables mirent les films sous clé, comme l’Inquisition l’aurait fait pour des écrits de sorcellerie et, plus tard, les firent détruire avec d’autres programmes jugés «inutilisables» ou «sans importance». (...).

Ted Joans, poète et ex-trompettiste, a raconté comment il avait entendu Ayler pour la première fois. Assis au bar d’un club de jazz de Copenhague, il attendait qu’Ayler et son groupe — Don Cherry à la trompette, Gary Peacock à la basse et Sunny Murray à la batterie — commencent de jouer. A côté de lui, le clarinettiste Albert Nicholas était en train de discuter des mérites respectifs de diverses anches avec deux jeunes musiciens locaux: «Je me tournai pour dire quelque chose à Albert Nicholas et, à ce moment-là, ils commencèrent: une explosion sonore sans précédent. Leur son était très différent, si rare et si sauvage — c’était comme si l’on avait crié fuck dans la cathédrale Saint-Patrick pendant la messe de Pâques. Les mains d’Albert Nicholas tremblaient, il renversait de la bière partout. (...) C’était comme le gigantesque raz de marée d’une musique qui faisait peur. Elle submergeait tout le monde. Quelques Danois réagirent en sifflant grossièrement, d’autres crièrent aux musiciens de se taire. Je restai là, pétrifié... Leur musique n’avait rien à voir avec tout ce que j’avais pu entendre auparavant.» (...).

Albert Ayler était né le 13 juillet 1936 à Cleveland, dans l’Ohio. Il était l’aîné de deux fils. Donald Ayler, qui devait par la suite jouer de la trompette avec lui, était de six ans son cadet. Un troisième enfant, une fille, mourut à la naissance. Son père, Edward, jouait du saxophone dans le style de Dexter Gordon et avait une certaine réputation sur le plan local; il chantait et jouait également du violon. La famille habitait Shaker Heights, un quartier résidentiel agréable, où Noirs et Blancs se mêlaient. Les enfants Ayler grandirent dans un climat de ferveur religieuse et dans le respect des valeurs de la petite bourgeoisie noire. En 1966, Beaver Harris habita quelque temps chez eux, après avoir joué avec les deux frères dans l’auditorium de la station de radio W.e.w.s. «Sa mère, dit le batteur, était quelqu’un de très mystique, aux opinions bien arrêtées, et active dans l’église. Ils croyaient en beaucoup de valeurs spirituelles.»

D’après sa mère, Myrtle, dès l’âge de trois ans «Albert soufflait dans tout ce qu’il trouvait». Dès qu’on diffusait des big bands, il allait se placer près de la radio, saisissait un tabouret, portait un des pieds à sa bouche et «jouait» avec Lionel Hampton ou Benny Goodman. Edward Ayler, frustré par sa propre incapacité de faire une carrière musicale, commença de lui apprendre à jouer. A l’âge où la plupart des enfants traînent dans la rue, jouent au baseball, Albert devait rester chez lui pour travailler. Son premier instrument fut le saxophone alto, et l’enseignement de son père dura quatre ans. Au terme de cette période d’apprentissage, ils jouaient en duo, le dimanche, à l’église. Lloyd Pearson, un saxophoniste qui dirige un orchestre de jazz-rock à Cleveland, connaissait Ayler depuis le jardin d’enfants. De deux ans son aîné, il se souvenait de lui quand il était en dizième, alors qu’il donnait des concerts en solo sur un instrument qui était presque plus grand que lui.

Albert Ayler se souvenait d’avoir été amené par son père aux concerts d’Illinois Jacquet et Red Prysock, deux saxophonistes qui savaient «chauffer» les foules. Chez lui, on écoutait surtout des disques de Lester Young, Wardell Gray, Charlie Parker, et aussi bien de Freddie Webster, un trompettiste de Cleveland dont les rares œuvres enregistrées devaient, plus tard, influencer le plus jeune des Ayler.

A dix ans, Ayler commença d’étudier au Conservatoire avec Benny Miller, musicien qui avait joué avec Charlie Parker et Dizzy Gillespie. Il y resta sept ans, et c’est là que sa prodigieuse technique allait se développer. A la John Adams High School, il était toujours premier soliste de l’orchestre de l’école — il jouait aussi du hautbois. Alors qu’il était dans la fanfare de l’école, il se fâcha un jour contre la musique écrite et, alors qu’on le réprimandait, déclara qu’il pouvait très bien se passer de partition. Le chef de la fanfare l’y autorisa, mais ajouta: «Si tu joues une note de travers, tu es renvoyé». Bien sûr, remarquait fièrement Edward Ayler: «Il ne joua jamais de travers!».

|

|

|

|

|

«Quand à New York nous avons entendu Ayler pour première fois, ce fut un problème...» (Lacy)

|

|

|

|

«Le moins que l’on puisee dire, c’est qu’ici les critères classiques d’appréciation ne nous sont plus d’un très grand secours. Le point de vue énergétique remplace le point de vue esthétique...» (Jean-Louis Chautemps)

|

|

|

|

AYLER EN EUROPE (19?)

«Ce n’est pas tant le refus, le rejet du jazz traditionnel,

mais plutôt la distance par rapport à lui qui importe ici.» (Chautemps)

|

|

|

|

«Quand la musique change, les gens changent aussi. Il y a longtemps que, dans le jazz, la révolution a eu lieu. Mais, cette année, quelque chose vient d’arriver. Partout les gens demandent: que se passe-t-il, que se passe-t-il?

Il semble qu’aujourd’hui le monde cherche à se détruire. Et pourtant beaucoup de gens parviennent à juger le monde avec un regard objectif. Ils voient la méchanceté, l’hypocrisie, l’injustice, et le dur travail que doit fournir l’être humain pour gagner très peu de chose. Si seulement nous voulions bien penser à ces choses, en pénétrer notre conscience intérieure — spirituelle — nous comprendrions qu’il nous faut livrer une bataille sans fin (avec nous-mêmes), avant de triompher de tous les obstacles, avant d’avoir acquis le désir véritable de changer.

La musique que nous jouons aujourd’hui aidera les gens à mieux se connaître et à trouver plus facilement la paix intérieure. L’inspiration nous est à tous nécessaire. Elle peut venir d’un mot, d’un paragraphe dans un livre, d’une peinture, d’un poème, d’une chanson, de nombreuses choses, en somme. Mais, en vérité, rien ne peut vraiment arriver si l’on n’est pas prêt.

La musique que nous jouons est une prière, un message venant de Dieu. Nous partageons tous une même émotion, mais cette émotion se manifeste différemment selon la personnalité de chacun. Pour notre malheur, le décor peut provoquer en nous des émotions vulgaires, telles que l’envie, la convoitise, le ressentiment et le mépris.

Nombre de personnes ne sont pas touchées par le Saint-Esprit. Le Saint- Esprit nous conduira tous, un jour, à travers le monde.

Voyer l’histoire du jazz: Bolden, Armstrong, Bird, Monk, Coltrane, Taylor, Ornette, etc., tous avaient leur façon propre de voir les choses, de nouvelles idées, l’espoir d’une esthétique nouvelle qui ne connaîtrait pas la destruction, que, ni le pouvoir, ni les structures établies ne seraient à même de tuer. (...) La liberté n’est pas le privilège d’une seule génération; c’est une conquête qui doit être chaque fois entreprise de nouveau. La liberté est victoire...» (A. Ayler, no 125.)

|

|

|

|

|

A la même époque, Albert commença de s’intéresser au golf. Il dirigea l’équipe de l’école à une époque où c’était encore un jeu réservé exclusivement aux Blancs et où les seuls Noirs tolérés sur les terrains étaient caddies ou chargés de l’entretien. Les nombreux trophées qu’il remporta trônent toujours sur la cheminée de ses parents, et ses succès dans ce sport «ségrégué» lui valurent un prestige considérable. (...).

A quinze ans, la réputation d’Ayler dépassait déjà le cadre de l’école et de l’église. Pearson monta un orchestre, Lloyd Pearson and his Counts of Rhythm, dans lequel il jouait du ténor et Ayler de l’alto; les deux adolescents commencèrent à se dérouiller dans des jam-sessions locales. Le Gleason’s Musical Bar était l’endroit où les musiciens de passage allaient chercher leurs sidemen, et faire partie de l’orchestre de ce bar, dirigé par le guitariste Jimmy Landers, constituait une étape importante. C’est là qu’Ayler rencontra Little Walter Jacobs, harmoniciste d’Alexandria, en Louisiane, qui avait mis au point une approche chromatique unique en travaillant avec Muddy Waters. Il joua dans plusieurs clubs locaux avec lui, puis Walter l’emmena en tournée. Pearson faisait également partie du voyage. «Quand il obtint cet engagement, il était tellement surexcité qu’il pouvait à peine y croire, se souvient Edward Ayler. Il est revenu à la maison en hurlant: «Ils me prennent avec eux, ils me prennent, moi!»» C’était, néanmoins, une expérience éprouvante pour un jeune bourgeois: les autres musiciens étaient de grands buveurs, des bluesmen «campagnards» du Sud profond, des gens presque illettrés. Son salaire était si maigre qu’il devait emporter sa nourriture. «Cette façon de vivre était complètement nouvelle pour moi — boire beaucoup et jouer très dur. Nous voyagions toute la journée, et quand nous arrivions enfin, nous sortions nos instruments et jouions».

Ayler passa deux étés sur la route avec Little Walter and his Jukes, mais, au début, l’harmoniciste lui reprocha son incapacité à tenir une note, ce qui plaisait beaucoup à leur public. Le jeune saxophoniste travailla dans cette direction et ils furent bientôt sur la même longueur d’onde. Il considérait qu’ «avoir passé quelque temps parmi ces gens aux fortes racines» avait joué un grand rôle dans son évolution. Pour Ayler, le passé, de manière évidente, participait du présent: «Blues et rythme — comment peut-on éviter ça? Il a fallu passer par là pour en arriver à ce que nous avons maintenant».

Puis Lloyd Price, chanteur de La Nouvelle-Orléans, emmena le jeune saxophoniste en tournée; ensuite, pendant quelque temps, avec Pearson, il traîna au Barbershop de la 55e Rue, un endroit fréquenté par les «durs» et les proxénètes locaux. (...)

A sa sortie de l’école, Ayler avait formé un orchestre de rhythm and blues, mais son existence fut brève. Il passa un an à l’université, mais, par manque d’argent, renonça à ses études et s’engagea dans l’armée. (...) On donna à Ayler le surnom de «Little Bird» à une époque où les autres saxophonistes de Cleveland s’efforçaient plutôt de «hurler» et de jouer sur le temps — une attitude qui n’était guère étonnante dans la ville natale de Bull Moose Jackson. Ayler et Pearson concentraient tous leurs efforts sur l’étude des accords et cherchaient à élargir leur répertoire. «Al jouait comme Charlie Parker et tous les autres, il pouvait jouer beaucoup de thèmes différents, des ballades, etc. Ensuite, des gars ont dit qu’il ne savait pas jouer, mais je me le rappelle quand il a commencé, et qu’il jouait n’importe quel standard, comme si c’était tout simple. Avant qu’il parte, il en savait plus que tous les autres.»

Ayler avait vingt-deux ans quand il entra dans l’armée. Il y resta trois ans, dans les Special Services Bands. Pendant six à sept heures par jour, il faisait de la musique de concert, et le reste de son temps était libre, il le consacrait au développement de ses propres idées: «à essayer de trouver une nouvelle façon de jouer qui serait bien à moi».

Beaver Harris, qui devait par la suite enregistrer et «tourner» avec lui en Europe, le rencontra à l’époque où ils étaient tous deux en garnison à Fort Knox, dans le Kentucky. Il était également attaché au Special Services, mais pas en tant que musicien; sa préoccupation essentielle, à cette époque, c’était le baseball. Quand il avait quartier libre, il pouvait se mêler aux musiciens, parmi lesquels on comptait Stanley Turrentine et Chuck Lampkin, batteur qui joua avec Gillespie au début des années soixante. (...) «Nous nous entendions toujours bien, dit Beaver Harris, ce qui n’était pas le cas avec d’autres musiciens. Il n’arrivait pas à communiquer avec Stanley Turrentine. Stanley était une «pointure», quelqu’un qui avait travaillé avec Charlie Parker, Dexter Gordon, Gene Ammons, Lockjaw Davis... Il avait donc plus d’expérience qu’Albert, plus de ce qu’on pourrait appeler la soulité. C’est une qualité qu’on ne peut pas mesurer chez un Noir, tous l’ont plus ou moins, mais certains musiciens jouent de telle façon qu’elle est dominée par leur technique. C’est ce qui arrivait parfois à Albert, alors que Stanley était strictement un musicien soul».

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pendant quelque temps, Ayler et Harris jouèrent ensemble, ils donnèrent quelques concerts à Louisville, la ville la plus proche, avant que le saxophoniste s’embarque pour l’Europe. Il était en garnison à Orléans, mais allait souvent à Paris, où il jouait dans divers clubs. Son intérêt pour la musique militaire — Il connaissait toutes les marches», dit Beaver Harris — fut aiguisé par les fanfares militaires françaises. Il s’attacha plus particulièrement à l’hymne national, «la Mayonnaise», comme il l’appelait. Par la suite, il se rappela cette période, qui avait contribué à la mise en forme de sa pensée musicale, en enregistrant Spirit Rejoice, un thème qui présente certaines ressemblances avec cette marche. C’est à cette époque qu’Ayler passa de l’alto au ténor. (...) «Il semble que ce soit sur le ténor qu’on éprouve tous les sentiments du ghetto. Sur cet instrument, on peut vraiment hurler et dire la vérité, déclara-t-il à Nat Hentoff. Après tout, cette musique vient du cœur de l’Amérique, l’âme du ghetto». Il visita le Danemark et la Suède, pays qui s’est toujours montré hospitalier pour les musiciens noirs. Il n’est pas surprenant que ce soit d’abord là que ses experiences aient été considérées avec respect; il envisageait d’y retourner aussitôt après sa démobilisation. Libéré en 1961, en Californie, il rencontra le comédien Redd Foxx. Les musiciens locaux le rejetèrent, comme ils l’avaient fait avec Ornette Coleman douze ans plus tôt; mais comme Erroll Garner, qui l’avait entendu à Amsterdam le soir où Don Byas avait été «converti», le comédien lui dit: «Joue ce en quoi tu crois».

De retour à Cleveland, ses tentatives pour mettre en œuvre ses idées révolutionnaires furent accueillies avec incrédulité par la plupart des musiciens. La première réaction de Pearson fut de penser que l’armée lui avait dérangé l’esprit et qu’il n’avait pas touché à son instrument pendant toute la durée de son engagement. «Je me suis dit: Merde, il est devenu complètement toqué!». A cette époque, tout le monde improvisait sur les accords — si on ne le faisait pas, les gens disaient qu’on ne savait pas jouer. Il était rejeté par le public, par les musiciens... Tout le monde riait de ce style, parce qu’ils n’avaient jamais entendu ça.

Pearson cacha sa surprise à son vieil ami, le laissant même jouer avec son orchestre pendant quelques jours, mais, appartenant à un milieu culturel où le sacré et le séculaire sont des domaines séparés, il était assez troublé par la façon qu’avait Ayler d’inclure des spirituals dans son répertoire. Pour lui, les spirituals étaient incongrus dans un night-club. Joe Alexander, alors le plus important saxophoniste de la ville, trouva, lui, qu’il était encore plus déplacé pour Ayler de vouloir jouer avec lui au soprano et de refuser les changements d’accords. (...)

Ayler décida qu’il avait assez de la «mentalité stupide» de ses compatriotes. Il dit à sa mère qu’il devait aller là où les gens comprenaient sa musique, même si, à l’époque, il y arrivait tout juste lui-même. «La musique n’était pas formulée tout à fait clairement dans ma tête. Je la jouais, mais elle venait lentement, pas immédiatement, comme maintenant». Il économisa pour pouvoir retourner en Suède, et, pendant les huit mois qu’il y passa, travailla dans un orchestre commercial. Néanmoins, chaque fois qu’il le pouvait, il allait jouer à The Old City ou dans le métro, pour les enfants: «Ils entendaient mon cri» disait-il.

Le propriétaire d’une petite compagnie entendit lui aussi son cri, par hasard. Le 25 octobre 1962, Bengt Nordstrom convainquit Ayler d’entrer dans son studio, où il fit ses premiers enregistrements pour la firme Bird Notes, devant un public de vingt-cinq personnes. (...) Trois mois plus tard il était invité à Copenhague pour enregistrer une émission pour la radio danoise. (...) C’est à cette époque que Don Cherry fit une tournée européenne avec Sonny Rollins. Le groupe comprenait également Henry Grimes et Billy Higgins. Ayler vint les trouver en coulisse à la fin du concert. Avec Cherry, ils allèrent au Jazzhus Montmartre, où Don Byas et Dexter Gordon jouaient. Le trompettiste fut invité à se joindre aux saxophonistes vétérans pour un ballad medley, puis Ayler proposa une version de Moon River qui étonna tout le monde. Cherry rapproche l’impact de ce morceau de celui que lui fit Ornette Coleman la première fois qu’il l’entendit. «C’est une chose qui, bien qu’étant entendue pour la première fois, semblait être familière».

A son retour en Suède, Ayler avait joué avec Candy Green, joueur de cartes professionnel et pianiste originaire de Houston, Texas, qui avait enregistré avec le chanteur de Blues Gatemouth Brown. Deux fois par jour, dans un petit restaurant, le saxophoniste retournait à ces «racines», pour gagner de quoi payer son loyer. A son retour du Danemark, il dit à Green qu’il ne pouvait plus «entendre» cette musique, parce qu’il venait de jouer avec Cecil Taylor. Sunny Murray, qui était venu en France avec Taylor, se souvient de leur première rencontre au Montmartre: «Personne ne voulait lui donner de travail, et ça le déprimait. Quand il est venu écouter l’orchestre de Cecil, il s’est mis à crier: «J’ai enfin trouvé quelqu’un avec qui je peux jouer! Je vous en prie laissez moi jouer!» Alor on a dit: «Qui est-ce celui-là?» Je ne l’avaisjamais vu, mais Cecil l’a ensuite engagé». L’association d’Ayler avec Taylor fut de courte durée, car il y avait peu d’engagements. Ils travaillèrent ensemble au Take Three, à Greenwich Village, avec Jimmy Lyons à l’alto, Henry Grimes à la basse et Murray à la batterie. Coltrane et Eric Dolphy, qui jouaient tous les soirs au Village Gate, tout proche, venaient régulièrement les écouter. On commença à entendre Ayler un peu partout dans New York.

|

|

|

|

|

«Leur musique était réjouissance...Son disque nous a permis d’aller plus loin, plus vite, de gagner du temps...» (Steve Lacy, 1971)

|

|

|

|

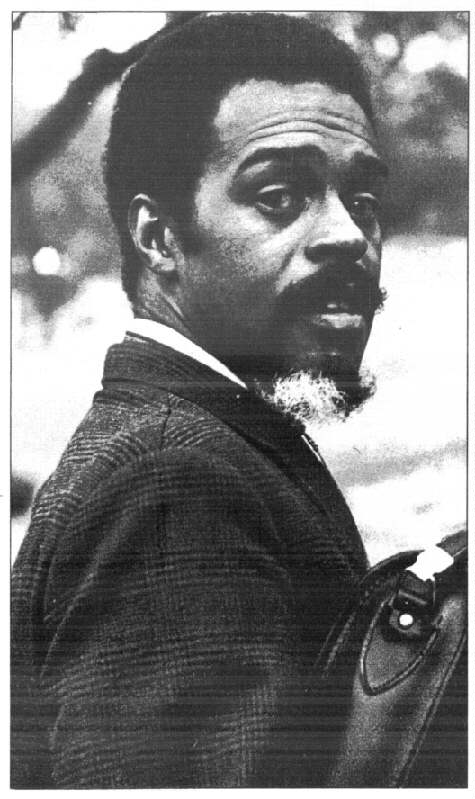

SAINT PAUL DE VENCE. JUILLET 1970: AVEC MARY MARIA ET STEVE TINTWEISS

«Je me souviens qu’en 1965 nous écoutions sans cesse son disque en trio,

Spiritual Unity... C’est après que quelque chose s’est cassé dans ma musique.» (Lacy)

|

|

|

|

A L’EPOQUE DES «SPECIAL SERVICES BANDS» (9 NOVEMBRE 1958)

«Il est évident que ce que nous lisons dans la musique d’Ayler — effets de rupture,

violence, dérision, etc. — n’est pas forcément ce qu’Ayler lui-même pensait y mettre.» (Jean-Louis Comolli)

|

|

|

|

«J’aimerais jouer quelque chose — comme le debut de Ghosts — que les gens puissent fredonner. Je veux jouer les airs que je chantais quand j’étais enfant. Des mélodies folkloriques que tout le monde pourrait comprendre. J’utiliserais ces mélodies comme point de départ et plusieurs mélodies simples se déplaceraient à l’intérieur d’un même morceau. D’une simple mélodie à des textures complexes, puis de nouveau à la simplicité et, de là, jusqu’aux sons Ies plus complexes, les plus denses.»

(A. Ayler)

|

|

|

«Qu’un type comme Ayler, après avoir longtemps cherché et souffert, ait pu être enregistré et entendu, c’est la preuve que tout reste possible. Mais il faut être toujours en éveil, et ce n’est pas facile. La révolution n’est jamais une chose confortable.» (Lacy, 192.)

|

|

|

«Nous essayons de rajeunir ce vieux sentiment du New Orleans que la musique peut être jouée collectivement et dans une forme libre. La force du timbre de Bechet, par exemple, la force de son vibrato, c’était fascinant. Il représentait pour moi le véritable esprit, la pleine force de la vie, ce que possédaient nombre de vieux musiciens et ce que n’ont plus les musiciens d’aujourd’hui. J’espère replacer cet esprit dans la musique que nous jouons. Nous essayons de faire maintenant ce que faisaient au début des musiciens comme Armstrong: leur musique était réjouissance. Et c’était la beauté qui apparaissait. C’était ainsi au début, ce sera ainsi à la fin. Un jour tout sera comme il doit être.» (A. Ayler)

|

|

|

|

|

A cette époque, certains de ses compatriotes de Cleveland commencèrent à s’intéresser à ce qu’il faisait. Frank Wright, bassiste à l’origine, commença à jouer du ténor dans un style proche du sien, ainsi que Mustafa Abdul Rahim, qui était un camarade d’école de Donald Ayler. L’une des premières haltes d’Ayler lors de son retour aux Etats-Unis fut la maison du trompettiste Norman Howard. Ils avaient grandi ensemble dans le même quartier, avaient joué ensemble, avant qu’Ayler parte à l’armée. C’est là, également, qu’il rencontra, et joua avec, Earle Henderson, qui était à l’époque un pianiste autodidacte particulièrement agressif. (...)

Néanmoins, il était evident pour Ayler que son avenir était ailleurs que dans cette ville du Midwest. En dépit du fait qu’il avait une femme et un enfant à Cleveland, il déménagea pour New York en 1963 et prit un appartement dans une maison appartenant à sa tante, sur Saint-Nicholas Avenue. Les saxophonistes Charles Tyler et Errol Henderson — qui jouait alors de la basse — habitaient dans un immeuble de la 130e Rue, à la hauteur de Lenox Avenue, avec d’autres jeunes musiciens de Cleveland et, plusieurs fois par semaine, Ayler traversait Harlem pour aller jouer avec eux. (...)

Ole Vestergaard Jensen, qui est à l’origine du disque d’Ayler pour Debut, se débrouilla pour le faire enregistrer dans les studios Atlantic. «Spirits», qui fut réédité ensuite sur Freedom sous le titre «Witches and Devils», contient quelques-uns des moments les plus majestueux d’Ayler et marque sa première apparition phonographique avec des musiciens de son envergure. (...) C’est vers cette époque qu’Ayler et les autres musiciens de Cleveland commencèrent à rendre régulièrement visite à Ornette Coleman dans son appartement en sous-sol de Washington Square. Il s’y produisit un échange d’idées considérable, et un «riche ami blanc» d’Ornette Coleman enregistra même la musique produite à l’occasion d’une de ces rencontres. Coleman, sur cette bande, .joue de la trompette, Ayler du ténor, Charles Tyler du saxophone en ut, Norman Butler de l’alto et du violoncelle et Henderson de la basse. Le «riche ami blanc» ajouta sa touche personnelle en jouant de la guitare, et c’est lui qui, finalement, mit ces bandes à la disposition d’un petit nombre d’initiés. Bien que ces enregistrements «pirates» circulent parmi les collectionneurs, enrichissant ainsi leur connaissance et leur compréhension de la musique, leur existence pose un problème. Comme le dit Henderson: «La musique que nous avons faite cet après-midi-là est maintenant un produit qui circule dans toute l’Europe, rapportant de l’argent à certains et une jouissance esthétique à d’autres, ça ne fait pas de doute. Néanmoins, aussi regrettable que cette situation puisse être en ce qui concerne la répartition des bénéfices de cet enregistrement, et le mépris envers les artistes que manifeste cette opération, c’est le seul enregistrement existant d’Albert Ayler avec, à la trompette, Ornette Coleman...». Mais, pendant son séjour à New York, Ayler ne se contenta pas de s’associer avec de jeunes musiciens. Il joua notamment avec Call Cobbs Jr, un musicien plus âgé, qui louait, lui aussi, une chambre dans l’immeuble de Saint-Nicholas Avenue. Cobbs (qui avait été l’accompagnateur de Billie Holiday et avait joué avec Lucky Millinder et Wardell Gray) est le pianiste d’autres bandes enregistrées à New York pour Debut. Les thèmes, rien que des spirituals, sont interprétés par Ayler au soprano, accompagné de Cobbs, Grimes et Murray. Plus tard, la même année, Ayler fit écouter ces bandes à Bernard Stollman qui s’apprêtait à constituer son catalogue de musique d’ «avant-garde» sur Esp et avait déjà accepté de l’enregistrer. Stollman fut choqué en entendant jouer des spirituals de cette façon, comme l’avait été Lloyd Pearson. La réaction d’Ayler fut de sourire doucement. «J’imagine, raconte Stollman, qu’il se disait que je comprendrais un jour». Mais ces bandes ne furent pas publiées.

En juillet 1964, contre l’avis de Cecil Taylor et d’autres musiciens qui pensaient que les artistes devaient, exiger un prix correspondant à leur talent, Ayler fit ses premiers enregistrements pour Esp. «Je pensais que mon art était si important qu’il fallait que je l’expose. A cette époque, j’étais musicalement dans un autre monde. Je savais qu’il fallait que je joue cette musique pour les gens». (...) En dehors du fait que Coltrane aida Ayler sur le plan financier, les rapports entre les deux hommes étaient très particuliers. Ils se parlaient sans arrêt, communiquaient par téléphone et par télégramme, et Coltrane était très influencé par son cadet. L’un de ces derniers vœux fut que Ayler et Ornette Coleman, l’autre influence importante de la fin de sa carrière, jouent à son enterrement. Les frères Ayler interprétèrent Truth is Marching in, accompagnés par Richard Davis et Milford Graves. Coltrane intervint pour faire obtenir à Ayler un contrat avec Impulse, mais ceci se produisit après qu’Ayler lui ait envoyé «Ghosts» et «Spiritual Unity». Peu après, Coltrane enregistrait «Ascension». Il appela Ayler et lui dit: «Je viens d’enregistrer un album et je me suis aperçu que je jouais comme toi». Réponse d’Albert: «Ne crois pas cela, tu as joué comme toi-même. Simplement, tu as éprouvé ce que je ressens et aspiré à une unité spirituelle».

(...) Ayler parlait tout le temps comme s’il avait eu une prémonition de sa mort. Avant même d’avoir signé un contrat avec Abc-Impulse ou d’avoir été reconnu et salué pour ses innovations, il rappelait le temps qu’il lui avait fallu attendre: «C’est un peu tard maintenant, il y a des années que je sens en moi cet esprit». Beaucoup de critiques approuveraient cette déclaration, car il la fit en 1966, alors que ses œuvres les plus complexes étaient déjà enregistrées. Il était passé rapidement de la complexité à la simplicité, éliminant tout ce qui n’était pas essentiel plus rapidement que tous les artistes qui l’avaient précédé. Comme s’il avait su que sa vie serait brève. — Valerie Wilmer (extrait de «As Serious As Your Life». Copyright 1977 by Valerie Wilmer — Quartet Books, 27 Goodge Street, Londres WIP 1FD, Angleterre. Traduction: Christian Gauffre.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Music

Swing Low on High

Albert Ayler resurrected

by Bob Blumenthal

“The ’60s were a period of musical upheaval, but time has separated the true innovators from the charlatans.” Surely, you’ve heard that one before. It seems that jazz didn’t have charlatans until Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor gave them license. Thank goodness their ranks are thinning. Time has made it harder to dismiss Coleman and Taylor, and Coltrane was always an innovator—after all, he could swing and play the blues.

For many, tenor saxophonist Albert Ayler is still the head mountebank of the avant-garde. His crooning, transmogrified tones, his stubbornly simple, even corny “folk” tunes, his thoroughgoing rejection of the beat and the chorus structure, his preoccupation with peace and love in song titles and interviews (so at odds with the sound of his music), and his sudden shift in the late ’60s to commercial formats all make Ayler an easy target. Swing Low Sweet Spiritual (Osmosis), the third addition to the Ayler discography to appear in the past 18 months, will give the doubters another opportunity to gloat. As one who will defend Ayler’s profound and essential contribution to free music, even I must admit to being disappointed with what should have been a made-to-order recital.

In early 1964, on the date of his first great recording session (reissued as Witches & Devils on Arista-Freedom but now out of print), Ayler also taped six spirituals and quasi- spirituals with a quartet completed by Call Cobbs on piano, henry Grimes on bass, and Sunny Murray on drums. Afro-American religious songs have been explored often by jazz musicians (James Moody cut a stirring “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen” in 1955), but hardly so exclusively. And in 1979, many listeners were stunned not only by Archie Shepp’s sensitive playing on Goin’ Home (SteepleChase), but also by the record’s gospel program. Given Ayler’s proclivities for melodies that suggest communal prayer songs, and given his cosmic outlook, Swing Low Sweet Spiritual is both in character and potentially more acceptable to listeners grounded in musical verities.

The results are fascinating, as much for what isn’t there as for what is, but only partially satisfying. A rolling gospel tempo is established for “When the Saints Go Marching In,” and Ayler, in a rare soprano-sax solo, serves up bluesy, undulating lines that would fit comfortably in a traditional New Orleans ensemble. Elsewhere the tempo is rubato, the mood is dirge-like in the manner of Ayler’s slow originals, and the primary concern is with melody statement. Cobbs, far more cogent than in the rollercoaster harpsichord accompaniment he would later provide Ayler, plays some reflective introductory choruses, and Grimes fills out the saxophone statements with patches of stately abstraction; Ayler, however, dispenses with variations almost totally, preferring instead to bring his massive, vibrato-laden tone to bear on the familiar themes.

Such conservatism highlights one of the most personal and overpowering tones in jazz. The spreading low notes and veering squeals, the abrupt and extreme shifts in register and dynamics, the mammoth breath control and unrelieved intensity all come together here and receive reinforcement from the material. If Ayler has always suggested a Wailing Wall supplicant in a fit of trance-like frenzy, the music offers focus and foundation for his lamentations, a recognizable context for talking in tongues. Without dampening his fervor, these spirituals locate it historically, making it sound anything but contrived. In terms of both Ayler’s musical and extra-musical pronouncements, these tracks are a testament to his conviction.

They may not be much more, however. Once past the initial theme statement, there is little of the nuance or invention of Goin’ Home, little of the cataclysmic rush of the best Ayler. Shepp, the other great post-Coltrane saxophonist of the ’60s, does so much more with “Deep River,” “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” “Goin’ Home,” and “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” because his embellishments are not merely textural. This is surprising, since Shepp is a radical by intellectual choice, a model of willed deviation. Yet he sounds both comfortable with and inspired by the spirituals, whereas Ayler, a far less self-conscious and analytical player, doesn’t allow himself the leeway he takes with his own compositions. Perhaps the material, including two takes of “Old Man River,” not exactly indigenous black music but fitting nonetheless, was too rich (Ayler’s musical career began at age 10, when he played funerals in a band with his father). Something inhibited his use of the accompanists, for Cobbs and Grimes embellish in spurts, at a remove from Ayler’s theme statements, and Murray’s contribution is minimal. This leaves Ayler and the melodies, and however promising the pairing of musician and repertoire may seem, it isn’t enough.

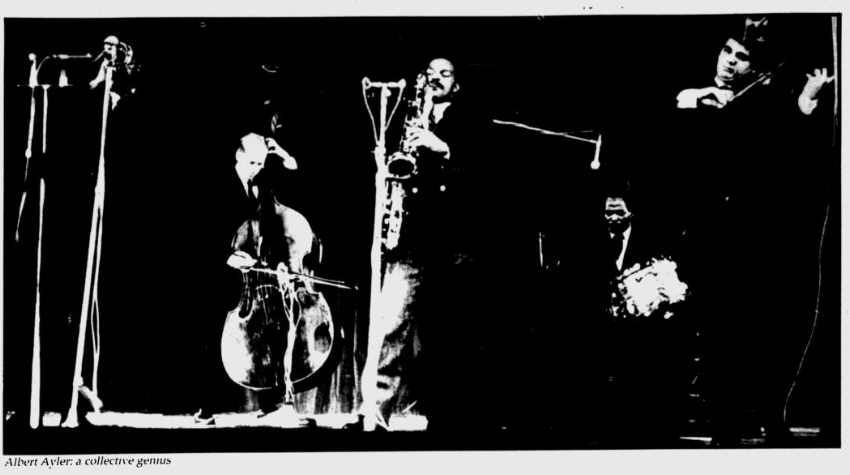

What’s lacking is the enveloping collective engagement that Ayler’s bands had perfected by the end of 1964, and which they were to maintain until Ayler’s rock deviation of 1968. Swing Low Sweet Spiritual implies what other recently unearthed Ayler performances make explicit: that his was a genius that depended upon, as much as it inspired, a similar abandon in his accompanists. This point is made best on Osmosis’s previous release, The Hilversum Session, which was taken from a radio broadcast at the end of a 1964 European tour by the definitive Ayler quartet, with Don Cherry on trumpet, Gary Peacock on bass, and Murray’s drums. The band rails and soars, as it had two months earlier on Ghosts (reissued by Arista-Freedom as Vibrations, now deleted) and two months before that (minus Cherry) on Spiritual Unity (ESP/Base). Here we confront all three hallmarks of Ayler’s style: tonal distortion, melodic naiveté, and tumultuous group improvisation; and the music is magnificent.

I am particularly struck by the sonic barrage Peacock and Murray unleash in tandem with Ayler, since this interaction (with each player tugging and pulling in unprecedented ways) is one of Ayler’s supreme innovations. Most of the best writing about Ayler, including Ekkehard Jost’s in Free Jazz and Martin Williams’s in Jazz Masters in Transition (both books recently reprinted by Da Capo Press), stress that the saxophonist’s solos are filled with phrases (Jost calls them “sound-spans”) that can be heard as thematic variations on his composed melodies. Although phrase shapes do often remain consistent, and the pattern of distortion may be systematic, it has struck me as misguided to focus on Ayler’s solos for melodic content when their fascination is rhythmic. And to hear Ayler for the rhythmic trailblazer that he was, the croonings and honks of his tenor must be surrounded by the splintered dissemblings of Peacock’s bass and the cymbal-centered whoosh (vocally reinforced) of Murray’s drums. Murray and (for a brief time) Ayler worked with Cecil Taylor, and the pianist’s role in liberating jazz from fixed meter cannot be underestimated; but Taylor always overwhelmed his sidemen, and his early Units never attained the three-pronged balance of Ayler, Peacock, and Murray. These were the men with impulses compatible enough to replace the beat with raw energy; it was they who moved rhythm from the audience’s feet to its spine.

Don Cherry completes the quartet by adding touches of restraint and fragility without allowing the others to overwhelm him. His playing on The Hilversum Session is by turns direct and dense, and he shadows Ayler expertly on the theme statements. Having previously worked with Coleman, Coltrane, Lacy, Rollins, and Shepp, Cherry was well prepared for the challenge of a major saxophonist, and his time with Ayler completed his apprenticeship. The years with Ornette Coleman did serve as Cherry’s basic formative experience, but even so committed a Cherry fan as Ekkehard Jost might reconsider the influence of Ayler’s childlike, universal melodies on Cherry’s later work.

These melodies assumed an even greater importance two years later, when Ayler returned to Europe with his reformed quintet. This group, heard on last year’s Lorrach/Paris 1966 (hat MUSICS), was no match for the earlier band, despite the strong support of bassist William Folwell and drummer Beaver Harris. Don Ayler was simply a skittering trumpet facsimile of his brother, without the poise or eloquence of Cherry; and the seesawing of Dutch violinist Michel Sampson’s leads froze the music. Yet there is added exhilaration in the melody statements, a level of ecstatic abandon Albert achieved with Don that accommodated even Sampson. These ensembles were now central to Ayler’s music, spreading to greater lengths, incorporating various Ayler tunes in medley fashion, resurfacing constantly between solos.

The emotional charge of these melodies as played by the Ayler bands is the most ineffable of Albert Ayler’s achievements, for the songs create an aura of spirituality that validates such titles as “Holy Family,” “Spirits Rejoice,” and “Angels.” This aura has moved many of those listeners and musicians (including John Coltrane, whose final period was shaped by Ayler’s example) who sound like displaced flower children when attempting to articulate Ayler’s importance. Don Cherry may have said it most succinctly when he called “Ghosts,” Ayler’s most famous tune, “mankind’s national anthem.” For all the talk of a new and enlightened consciousness in music, it was Ayler, his band, and his tunes that left a body of work so primal it seems to exist on another plane. Perhaps time will reveal this charlatan as a saint.

(Osmosis and hat MUSICS are available from New Music Distribution Service, 500 Broadway, New York, New York 10012.)

Back to Articles main menu

*

The Wire (No. 3, March 1983) - UK

.. THE TRUTH IS MARCHING IN

Two life-long ALBERT AYLER enthusiasts - Bill Smith and Brian Case - remember the legendary, lost tenorman.

THIRTEENTH OF February, 1966, a new era of enlightenment began. The overjoy of one’s first child. A girl. A celebration of some magnitude would begin.

Nineteenth of February, 1966 - The Lincoln Centre - NYC. The people’s section of Philharmonic Hall was filled, so we were forced to purchase the expensive seats. Front row centre. Titans of the Tenor, was the title of the show. Coleman Hawkins, Yusef Lateef, Sonny Rollins, and then Carlos Ward, Pharoah Sanders, John Coltrane, Jimmy Garrison, Rashied Ali, J C Moses and Don and Albert Ayler. This era, in the popular American press, was being proclaimed as dead. JAZZ IS DEAD.

Philharmonic Hall is quite what you’d expect, built for a Symphony, but not expecting the 40-minute symphony that ensued. The music was truly unbelievable. From Garrison’s flamenco opening, the music built and, as the confidence of the players strengthened, as their spirits became of one accord, so the music transcended ‘My Favorite Things’ and exploded into vocalised shout/song/holler. Sanders scream surrounded by Ali flurry. Coltrane knowing that this was a ‘new’ song. Albert so beautiful, singing praise so virile, me no longer a virgin, taken by a new power so real that most everything afterwards would seem not to happen. The truth is marching in.

‘This piece of music by Coltrane’s augmented band, was all solo music. There was no attempt made to produce any real group music. Probably there wasn’t time, for the Aylers were only invited to appear a couple of days before the concert. Apparently Coltrane had been trying to persuade the promoters to book Ayler’s own group, but when this failed he solved the situation by inviting them to play with him. (John Norris - Coda).

The silence at the performance end exploded into amazed appreciation.

Monday nights was Albert Ayler night at the Astor Playhouse - a small, funky old theatre in the Village. Now we could hear him in total. The players in the band are almost a description in themselves. Albert and Don Ayler, Charles Tyler (alto), Joel Freedman (cello) and Ronald Shannon Jackson (drums). It’s such a warm feeling that one gets from old theatres, the slightly tatty environment being a comfortable parallel with one’s life. It feels, that for the first time the parameters of jazz are being redefined, for although Ornette’s and Coltrane’s saxophone music have made positive steps away from boredom, they still rely, in this period, a great deal upon the tradition. Here is a new music, not necessarily in notation, but in spirit. Time is free-floating rhythm, escaping from clockwork meter, throwing off the last confinement of European traditions. A pure American music. Already there are comparisons by critics, having as they do to link everything with past standards, that it is based in European folk rounds. I still search for this mythological European music that is so volatile it makes the soul tremble.

Just around the corner was Slugs, a lower East Side neighbourhood bar. Much of the new music was being performed there. Spit and sawdust, I guess, would be a description. In NY State waiters are required by law to wash their hands after using the toilet. There seems to be no washbasin. Had gone there with Elizabeth Van der Mei and Albert, just for a beer. The Burton Greene quartet is the music. The saxophonist is Frank Smith, a white tenor-player, sounding already so much like Albert. A musician leaps up from the audience, knife thrust forward, ready to damage the imitation, wanting only to hear the master. The truth is marching in.

By now, in New York, Albert’s reputation is building strong controversy, and he will, of course, be challenged by the jazz standards. One afternoon, at the Dom, a small club opposite the Five Spot, on Saint Marks Place, the tournament will begin. Tony Scott, a liberal bopper, runs the club. He has a rhythm section on this day, consisting of Henry Grimes (bass) and Eddie Marshall (drums). Pretty classy. The song is ‘Summertime’. Albert’s tenor is borrowed from Tony Scott, but the higher register unison lines are crystal clear, and soon - as was often the case - he is alone, singing his beautiful song. The truth is marching in.

I saw Albert only twice after this, once a year later at the London School of Economics, in England, where he was being filmed by the BBC. A show of ‘animal music’ that was never broadcast. And then in June of 1967, at last recognised, he appears at the legendary Newport Festival. Albert in two-tone beard, white suited, shining in stage lights. The truth is marching in.

In November 1970, Albert Ayler was found murdered, his body floating in the East River, NYC. The Truth Is Marching In.

Bill Smith

ALBERT AYLER: Swing Low Sweet Spiritual (Osmosis Records 4001)

Recorded: Atlantic Studios, NYC - 24th February, 1964.

Side One: ‘Going Home’; ‘Old Man River’; ‘Nobody Knows The Trouble I’ve Seen’. Side Two: ‘When The Saints Go Marching In’; ‘Swing Low Sweet Spiritual’; ‘Deep River’; ‘Old Man River’.

Albert Ayler (ts, ss); Call Cobbs (p); Henry Grimes (b); Sunny Murray (d).

ALBERT AYLER: Lorrach/Paris 1966 (Hat Musics 3500)

Recorded: S W German Radio - 7th November, 1966, and Radio France - 13th November, 1966.

Side One: ‘Bells’; ‘Jesus’. Side Two: ‘Our Prayer’; ‘Spirits’; ‘Holy Ghost’. Side Three: ‘Ghosts’; ‘Ghosts’. Side Four: ‘Holy Family’.

Albert Ayler (ts); Don Ayler (tpt); Michael Sampson (vln); William Folwell (b); Beaver Harris (d).

ALBERT AYLER QUINTET: At Slug’s Saloon, Vol One & Two (Base 3031, 3032)

Recorded: Jan Werner- lst May, 1966.

Side One: ‘Truth Is Marching In’. Side Two: ‘Our Prayer’, Side One: ‘Bells’. Side Two: ‘Ghosts’.

Albert Ayler (ts); Don Ayler (tpt); Michael Sampson (vln); Lewis Worrell (b); Ron Jackson (d).

Given the fact that practically all of his best work - Spiritual Unity, Spirits, Ghosts and the recently released Prophecy and Hilversum Session - was recorded in 1964, one goes first for the legendary spirituals album, and is massively disappointed. I suppose one expected those near-pentecostal freak-outs that occur on his own hymn-like originals, the tenor hysterically howling in the aisle while the group maintains the sobriety. Ayler here sticks reverently to the tunes and is dull. His soprano nowhere approaches the passion shown on My Name Is Albert Ayler, and is often out of tune, while his tenor - apart from some busking in the vibrato and whimperings at the close of a phrase - is careful rather than caring. All the duet sections with the corny Call Cobbs remind one of an Edwardian recital of ‘In A Monastery Garden’, one posing with a roll of sheet music, the other with rosewater on his hair. Murray is inaudible - he often was - and the only drama and adventure comes from Grimes, who succeeds in giving the leader some momentum.

As a missing piece of the jigsaw, Swing Low Sweet Spiritual has the fascination of finding, perhaps, Cecil Taylor doing his best on ‘The Girl With The Flaxen Hair’; as music, unfortunately, it isn’t up to much. What did Ayler think he was doing here? Probably looking for a ready-made armature to house his improvisations - an old form which would carry the burden of black American history and conventional spirituality for him. It’s lonely being far out. Mingus and later, the Art Ensemble and Air, managed to roll out the whole heritage within a number; Ayler never really reconciled his antique forms with his wildly contemporary improvisations. The tragedy is that before he became self-conscious about it, letting the music follow its head, he made the most artistic sense.

None of his post-1964 idioms came near the intensity of which he was capable. New Grass, the attempt at a crossover into r&b and soul, was frequently daft, while the collaboration with Mary Maria was disastrous. The other albums here come from Ayler’s collective period in which the Moorish-Balkan pat-a-cake structures buckle in the middle to release famous breaks. There is nothing here that you don’t already know from Love Cry and Greenwich Village - except that Paris variations on ‘Ghosts’ sound as if the group is desperate to ring the changes on all those predictable swoons and ceremonials. One is not surprised. Ayler must have known that he had painted himself into a corner as far as improvisation was concerned. Most of his solos sound like Ornette on violin, brutally high ululations that register little beyond a one-dimensional fury.

Of the two collections, the Lorrach/Paris is the better recorded. The ensembles on the familiar ‘Bells’, ‘Our Prayer’ and particularly ‘Holy Ghost’ are charming - and consequently at odds with the uniformly end-of-tether solos. Sampson is clear for a change, and comes on like Barry Guy on violin on ‘Bells’ to good effect, whereas the At Slug’s Saloon recording reduces him to whiskery whistlings. There’s quite a bit of murk at Slug’s, and a lengthy conversation across ‘Bells’. One finds oneself grateful for the odd divergence in intonation or placing in both lots of routines.

Albert Ayler has been dead 13 years. His best work still shakes the heart like nothing else, but we are talking about five albums from a single year, and a few great moments. He hadn’t lost it, any more than he couldn’t find it, as ‘Bye Bye Blackbird’ and ‘For John Coltrane’ prove, but he was possibly so driven by the knowledge that he had found a route to the spirit that nobody wanted that he dissipated his power looking for popular formats.

Gary Giddins maintains that Ayler’s synthesis ‘blanched in a flower power compromise’. It blanched in something all right. It’s a problem of our times.

Brian Case

*

The Wire (No. 6, March 1984 pp.27-28) - UK

In response to The Wire’s two previous Albert Ayler pieces, Mike Hames reveals the true circumstances of the saxophonist’s death, and reassesses his controversial experiments with soul, R&B and gospel music.

ISSUE THREE OF The Wire raised some points that need answering. Firstly, Bill Smith asserted that Albert Ayler was murdered. Many have assumed this to be the case, because there was no inquest and nothing was said by his family. It was therefore assumed that his family did not know the cause of his death. Shortly before that third Wire was printed I published the following as an addendum to my book of discographies:

THE DEATH OF ALBERT AYLER

Mary Parks, second wife of Albert Ayler who performed with him under the name Mary Maria, wrote to me about the circumstances of his death. She did not reveal these at the time, because she did not want to embarrass his family, but now feels that the rumours that have circulated should end. The circumstances of Albert Ayler’s death were extremely harrowing for everyone concerned. Only after much meditation and prayer has Mary been able to write to me about these matters. The following account is based on what she wrote.

The strains of surviving as a musician in New York seriously affected the mind of Albert’s brother, Donald. Their mother blamed Albert for introducing Donald to the musician’s life. She and Donald continuously pressed Albert to look after Donald. Albert helped in several ways, but he did not want Donald to live with him or play with him. After two years of aggravation from his brother and demands and threats from his mother Albert could no longer cope. Although Donald was finally receiving hospital treatment after a nervous breakdown, Albert could not be convinced by Mary that the situation would end.

Albert told Mary that his blood had to be shed to save his mother and his brother. He even told her how he wanted the rights to his music to be divided after his death. She rang his father but he didn’t seem to believe it. Mary’s sister then tried to dissuade Albert from taking his life and he promised to think it over.

One evening he said again to Mary, “My blood has got to be shed to save my mother and my brother.” Later that night he smashed a horn across the TV set and left the house. Mary called the police in desperation but they were unable to find him.

Albert Ayler’s body was found floating near the pier in the East River. The police told Mary that they checked with the coastguard who said they believe Albert took a ferry boat and jumped overboard near the Statue of Liberty—if it had been elsewhere the tides would have taken his body out to sea.

OTHER MATTERS

1. TRUE COMPANIONS

In the same issue of The Wire Brian Case raised some points which I wish to put in another light.

Something I find psychologically interesting is the fury of some critics and fans that Albert Ayler didn’t play in 1966-8 or 1968-70 as he did in 1964 or 1965. It is true that his 1964 recordings had the most dramatic impact on the world of music—and rightly so—but Brian is so blinded by their brilliance that he is unable to write rationally about his other work.

Brian even seeks to blame Albert’s truest companions. I would like to point out that from all accounts Call Cobbs was a nice human being—not ‘corny Call Cobbs’. Together with the (elsewhere) maligned Bill Folwell he was an honorary member of Albert’s family and a real support to him. Musically he was no Earl Hines—but then Albert didn’t require that. He played what Albert asked him to and was his longest associate. Both Call and Bill were humble enough willingly to step aside if Albert required and could get better players.

Brian asks what Albert thought he was doing on the 1964 spirituals session with Cobbs. I don’t know, but I understood that he didn’t want it issued at the time.

Brian calls the collaboration between Albert Ayler and Mary Maria (Mary Parks) a ‘disaster’. In human-terms the ‘collaboration’ offered Albert a haven of peace from his troubles. Mary also helped Albert’s career by staging concerts— including one of those subsequently released by Impulse. Musically she contributed to compositions on the New Grass LP, but only three titles with her singing were released during Albert’s lifetime and two posthumously. If Brian had read Val Wilmer’s As Serious As Your Life he would have realised that Mary was only occasionally added to gigs. Besides that, Albert made all his own decisions. Mary told me that she was not even introduced to the musicians she was playing with. For this reason she is not certain but she doesn’t believe that Bobby Few, Stafford James and Muhammad Ali had played with Albert before the sessions which produced the LP Music Is The Healing Force Of The Universe.

However, it should be noted that at the Fondation Maeght in 1970 Mary sang and played soprano sax on over half the pieces on the first day—none of which have been released. Harald Schönstein, reviewing the concert in Jazz Podium (October 1970), praised the intensity of her soprano work and then said ‘as a singer Mary Maria is no less exciting. She commands an expressive voice and knows how to use it’. Eugene Chadbourne in Coda (July 1974), reviewing the issued material from the following concert, says that the title ‘“Music Is The Healing Force Of The Universe”—with a lovely vocal from Mary Maria—is really where Ayler gets everything possible together and heals you.’

Of the records Brian reviewed (the 1964 spirituals & live sessions from 1966), he expects ‘near pentecostal freak- outs’, ‘Hysterical howling’, ‘wildly contemporary improvisations’ and ‘intensity’, but complains when he gets ‘famous breaks’, ‘end of tether solos’, and ‘brutally high ululations that register little beyond a one-dimensional fury’. One might be forgiven for asking if Brian prefers his fury two-dimensional or three?

2. THE LATER RECORDINGS

The remainder of these notes will look at what Albert said about his work up to 1966 and information and thoughts about his later career.

Albert’s work and recordings did continually change, and it is worth remembering W. A. Baldwin’s description of him as a ‘conservative revolutionary’ when looking at what he said in mid-1966 to Val Wilmer (Melody Maker 15/10/1966 and Jazz Monthly, Christmas 1966) and to Nat Hentoff (Downbeat 17/11/1966). Brian romantically suggests that Ayler ‘was possibly so driven by the knowledge that he had found a route to the spirit that nobody wanted that he dissipated his power looking for popular formats’. I think the following extracts conclusively demonstrate otherwise.

‘You have to make changes in your life, just like dying and being born again, artistically speaking. You become young again through this process . . .’ (JM)

Around 1960 ‘it seemed to me that on the tenor you could get out all the feelings of the ghetto. On that horn you can shout and really tell the truth. After all, this music comes from the heart of America, the soul of the ghetto.’ (DB)

‘The scream (elsewhere ‘vibration’—MH) that I was feeling then (c.1964-5) was peace to me at the time. That was the way I had to go then. Whatever was inside of me, something was happening and I did not know exactly what it was. America was going through such a big change and I’d been travelling all over, seen it all, and had to play it out of me. But now it’s peaceful. It’s more like a silent scream.’ (MM)

‘Everyone is screaming “freedom” but mentally everyone is under a great strain. But now the truth is marching in, as it once marched in New Orleans. And that truth is there must be peace and joy on earth. Music really is the universal language, and that’s why it can be such a force.’ (DB)

‘For me, he (Bechet) represented the true spirit, the full force of life, that many of the older musicians had—like in New Orleans jazz—which many musicians today don’t have.’ (DB)

‘We’re trying to do for people now what people like Louis Armstrong did at the beginning. Their music was a rejoicing.’ (DB)

Although Albert was talking of the changes in his music up to mid-1966, ‘old timers’ like Albert Nicholas, Don Byas and Call Cobbs had heard the message by 1964 or earlier. Louis Armstrong himself invited Don Ayler to play at a later date. (Cadence, February 1979).

Now let’s turn to the recordings: I assume that what Brian and others complain about is that Albert’s solos are too short on his 1966-7 recordings and they are more limited.

They are right—Albert did decide to restrict his solos. ‘Before we were just playing and at that time there weren’t too many people that could do that . . .’ (JM) Having played the ‘vibrations’ of his early years Albert left others to do that and turned ‘to rejuvenate that old New Orleans feeling that music can be played collectively and with free form.’ (DB) Don said the listener should watch the colours (pitches) move. To me that means that the solos themselves should be seen as colours—an integral part of the composition in that they are contrasting colours to the themes. Therefore the solos do not fill the role of a ‘conventional’ free jazz solo and they are restricted. This artistic decision created some excellent music. The drama and explosiveness of ‘Bells’ and ‘Truth Is Marching In’ led people to expect the walls of all sorts of Jerichos to fall. I can’t think of a more ludicrously inappropriate description than the Gary Giddins quote that Brian seemingly approves that his music ‘blanched in a flower power compromise’.

1967 saw a further change in Albert’s music. The proportion of march themes was reduced on the Impulse LP Love Cry in favour of some engaging ballads on which Call Cobbs—who was then playing regularly with Albert—plays electric harpsichord. Enough of Albert’s traditional themes remains for the LP to be considered by some critics to be acceptable within the canon of Albert’s work! This is a fine LP, though it’s a shame that more longer pieces were not recorded.

In April 1968 Albert performed ‘Songs Of Zion-New Opera: Universal Message: Songs Of David’ with five singers. The music press appears to have ignored it. In August he performed at the Cafe Au Go Go with Call Cobbs (piano and organ), Bill Folwell (bass) and Beaver Harris (drums). He also sacked his brother permanently. I’ve found no subsequent reports of performances in America, though Mary Parks and Leroy Jenkins tell me they performed with him in August 1970. I’ve found no American broadcasts or private recordings that have circulated from after July 1967. Work was extremely hard to obtain there in the late ’60s.

Critics talk of a decline and a dissipation of expression and energy in this period. To argue against this view other than on the issued evidence and the unissued material from the Fondation Maeght is impossible, but may be misleading, because there is so little of it.

Certainly Albert’s music changed dramatically in format—and more than once. With himself as the only ‘horn’ Albert needed a keyboard player. Call Cobbs’ experience with Billie Holiday and Johnny Hodges and his church organ playing enabled Albert to play lyrically, return on occasion to his own Rhythm and Blues background and express his spiritual concerns through more conventional forms. But also—as Ronald Atkins noted (Jazz & Blues, June 1973)—he was ‘able, in a sense, to feed off the piano chords’ and yet make his 1970 “Spirits” solo . . . seem as abstract as his (1964) version’.

Shortly after the Cafe Au Go Go gig, Albert recorded New Grass on which Bernard Purdie replaced Beaver Harris. This is a straight ‘soul’ record with instrumentals, songs and even a brass section. Albert plays well on it and it is an enjoyable record. He told Val Wilmer in 1966 that he found more spirit in soul, blues, etc. than in modern jazz, but despite its merits this record shows that the conventions of both are limited.

Those who heard ‘the great revolutionary’ turning ‘populist’ and playing soul were equally disturbed by the 1969 LP Music Is The Healing Force Of The Universe on which Albert jams unsuccessfully with blues guitarist Henry Vestine, accompanies and sings on spiritual songs and plays the bagpipes. (Further material was issued posthumously as The Last Album.)

Had Albert sold out? If so, not enough for Impulse. In fact his contract terminated well before those of Archie Shepp or Pharoah Sanders. The company didn’t even have the courtesy to confirm the termination in writing. I understand that Impulse say it had expired naturally, but Albert believed it had two years to run.

Albert’s soul record presumably grew out of his Cafe Au Go Go gig, which I hear was enjoyable, yet I doubt if it was more than a temporary move. The music from the Healing Force sessions deserves to be taken more seriously. If Impulse had forgotten the blues jams, which were an afterthought and detract from the other music, it would have clarified things for the lazy—myself included.

Bobby Few, the pianist on these sessions, may have known Albert from Cleveland but the group may not have been a working group—though it does work on the record. The ‘rhythm section’ sounds more like Coltrane’s 1966 group than any group that Albert formed. (Rashied Ali’s brother Muhammad is on drums). On ‘Masonic Inborn’ where Albert plays bagpipes—an instrument Coltrane also played—one expects Coltrane and Pharoah to burst in at any moment. ‘All Love’ also has moments that are reminiscent of Coltrane and, since Albert appears to play with a softer reed, on ‘The Birth Of Mirth’ for example, he has to work up to his harmonics a la Coltrane rather than leaping to them directly as in earlier days. Nevertheless the music remains ‘pure Ayler’ and three tenor instrumentals in particular (all on The Last Album) are an important addition to Albert’s work.

As we have seen, Albert—like many others in the late ’60s—felt the need to use the human voice and express his spiritual concerns. Any in-depth look at Albert’s life and views would have to consider these beliefs that lay behind and were partly expressed in his and Mary’s songs—and of course the community from which they came. Unfortunately I am not in a position to do this.

We don’t know what his ‘opera’ was like or whether he performed additional works of a similar nature. The music he wrote to his wife’s words on New Grass was soul. The music he wrote to her words on Healing Force is different again.

There are two versions of these songs. I prefer the unissued versions from the Fondation Maeght, which are more relaxed and joyful and Albert and Mary are both in good voice. The 1969 versions are given more tension by the ‘rhythm section’ and could be considered complementary. Albert’s daring vocal conception is evident on both.

Whatever the critics thought of his recordings from 1968 and 1969 most reviewers were happy with the final recordings from the Fondation Maeght. On some of the unissued material Albert plays a fair bit of soprano sax. Both days produced great music—the whole suffused with a joyful warmth. Eugene Chadbourne was moved to write ‘Albert plays better than he ever did before on record’. Personally I’d hate to have to select his finest recording for he gave us so many and in such varied settings. Albert’s music changed, but his powers never diminished. The truth was still marching in and the audience knew it and—as Harald Schönstein said—‘swamped him with ovations’. Let it come in.

MIKE HAMES

Back to Articles main menu

*

The Wire (No. 58/59, January 1989, pp. 60-63) - UK

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

my name is albert ayler

I’VE BEEN wondering lately if anyone listens to Albert Ayler any more. Eighteen years after his death, the man who, more than anyone else, shocked and dishevelled the jazz of his time has become antique. If Ayler came along today, his currency would be, if not exactly commonplace, no more sonically disturbing than many of today’s extremists.

Borbetomagus exploit the edges of Ayler’s art with a relentlessness that might have fazed Albert himself. Last Exit would just drown him out. Yet no saxophone screamers or noise merchants have truly mastered Albert Ayler. He organised his music in forms and emotions which, for their candour and determination, have never been surpassed. But it’s no use trying to sell Ayler as a sensation. In his dark, mysterious recordings he is pursuing a different goal.

People who heard him remember Ayler with a mixture of affection and sadness. Anyone who lived through the new jazz of the 60s tends to look back on it with nostalgia, as they do on everything else that happened in that decade. The outrage and bewilderment which once accompanied that music have mellowed (the alcohol turning to sugar, perhaps).

Ayler has left little to remember him by, though. His records were comparatively few in number, and fewer still remain available. His masterpieces for the New York ESP label have been in and out of the catalogue, although it’s valuable that at least Spiritual Unity is once again being distributed. John Coltrane, who admired Ayler enough to incorporate elements of the younger man’s music into his own playing, is more ubiquitous than ever; Cecil Taylor is an honoured and still vitally creative force; Ornette Coleman is a grandmaster lionised by disciples, pushing onward with his fusions; Eric Dolphy has taken a posthumous place as an instrumental virtuoso. The great Black masters of the avant-garde have received at least something like their due. Albert Ayler remains on the fringes, a shadowy name more spoken of than listened to, and not much spoken of at that. Even critics, who once raged over the properties of Ayler’s music, have left him alone. He is scarcely perceived as an influence. His time has gone, and Ayler has almost gone with it.

It’s not that history has been rewritten. It’s that Ayler’s force has been rationalised away into a kind of dead zone. He was bad for jazz on too many levels to have survived as a primary agent. Even in his own lifetime, when the livid power of his early music led him nowhere in either critical or commercial terms, Ayler squared off his most radical tendencies. He came in hard and fast, and was broken quickly as a result. Cecil Taylor has proved to be as radical as Ayler, but his music grew more slowly and was in any case delivered in less confrontational terms.

Ayler was unprecedented in the manner of his music. At the time of his first (official) recordings in 1963, jazz had gone as far afield as Taylor’s “D Trad, That’s What”, Coltrane and Dolphy’s “Africa” and Coleman’s “Free Jazz” - imposing statements, but all comparatively digestible to adventurous contemporary listeners. My Name Is Albert Ayler, and the first records he made in New York, marched ahead of all of these. There is a case for

saying that we’ve moved no further since.

AYLER WAS already 27 when his first New York recordings were made. He was born in Cleveland, Ohio in 1936, and like so many of his generation of musicians he served a rhythm and blues apprenticeship. His crucial association in the 50s was with Little Walter’s band: Walter Jacobs played harmonica in a brutal, cleaving style that was not so different from Ayler’s saxophone multiphonics (Albert played alto then, and switched to tenor while in the army in 1958). He built his early reputation in Europe, following his discharge, having found little appreciation in the US for his gathering conception. My Name Is Albert Ayler was recorded in Denmark, a chaotic assemblage of standards and one free piece, culminating in an unholy rendition of “Summertime”. The song becomes an extravagant, blaring music, the saxophone humping up and down over the uncomprehending rhythm players.

This first session sounds like a prelude to something awesome. Ayler’s music burst in 1964. His records from that year arc transfixing in their power and intensity. But it’s a personal, not an impossible music. “We play folk tunes from all over the world, like very, very old tunes,” he said, much later. Seeking the source of Ayler’s music was compulsory activity: it’s as though people couldn’t believe a man had the gall to play the way he did, so they had to determine his previous incarnations. Albert was detected in pygmy music, in New Orleans dirges, in gospel hollers and raw country blues; his bands were compared to old marching bands, ancient European folk ensembles, military brass sections. One could make a case for all of these, but it obscured the fact of Ayler himself, a middle-class black who played an excellent golf game but had the street .smarts to be friendly with his neighbourhood hustlers. Driven with missionary fervour, he seemed ready to overthrow the notion of the jazz tradition. The music wasn’t some kind of folk accident but the product of a single, furious inspiration.

What did this inspiration sound likc? The records remain a stunning experience. The greatest of them might be Spiritual Unity, made with Gary Peacock (bass) and Sunny Murray (drums), released by ESP. Allegedly, the engineer set the tapes rolling and fled the studio when he heard the music begin. Everything about the record is extraordinary. The sleeve, an illustration by Howard Bernstein, depicts a naked protean figure cradling a saxophone. On the other side, bleached portraits of the players are placed between the forks of the symbol Y, “the rising spirit of man”. A booklet given away with the first copies of the record includes a commentary by Paul Haines, the poet best known for his libretto to Escalator Over The Hill. He calls Ayler’s sound “that of a diseased pearl”.

The first sound on the record is a shock: the tenor saxophone blurting out the beginning of a melody line, out of a clear pitch, before bass and drums fall in beside it. “Ghosts” was Ayler’s most enduring melody, and he played it for the rest of his career. There are two versions on Spiritual Unity, opening and closing the record. The theme itself has the simple appeal of a rhyme; it sounds as though it might have been composed on a bugle, as many of Ayler’s later themes also suggest. But from there the trio move into dimensions of vast complexity.

Ayler’s solos assault a passive listener. Everything in his sound is extreme: the mountainous volume, suddenly feathering off into small crying sounds, the tone he gets, cracked from the inside, touching all the false registers of the horn, shrill and hoarse at the top, bottoming out into a cavernous low honk; the phrases blasted out until his lungs are empty. In the second version, “Ghosts” becomes an exorcism of something unnameable in the saxophonist’s music. The terror in this performance lies in the way an exultant if ominous mood is annihilated by Ayler’s solo, a marathon of split tones, bellowing cries and herculean crescendoes. He hammers on and on. It isn’t a quest for fulfilment, like Coltrane’s music. These are the throes of something already achieved. Something fantastic seems to fly out of the music, a moment of collective hysteria that subsides as the tenor dies out.

Albert Ayler isn’t the only remarkable thing about Spiritual Unity. The record also marks the end of the jazz rhythm section. Sunny Murray dispenses with timekeeping and plays a continuous, flashing line of cymbals and tapping snare interruptions - gently, almost wispily, creating an amazing contrast to the leviathan weight of Ayler. Gary Peacock follows his own line, a blur in the middle, roving between the two measures and offering his own dense form of counterpoint.

It’s at once a complete ensemble music and a vehicle for a gigantic personality. “The Wizard” and “Spirits” are, basically, more of the same, although the internal logic of “Spirits” will prove that Ayler wasn’t charging randomly into his music. There is a marvellous moment about half-way through the first “Ghosts”, when the trio seem to pause for an instant before collectively gathering themselves and moving onward.

AYLER’S MUSIC receives its most striking portrayal here, and in the companion records Witches And Devils, Vibrations (alias Ghosts), and The Hilversum Session, the latter two involving Don Cherry as a foil who stands slightly apart from Ayler, offering his own, raised-eyebrow improvisations to the strident sounds around him. “Mothers”, from Vibrations, is a stark dirge which none of Ayler’s critics could take seriously: played remorselessly straight, the saxophonist using a vibrato that shivers like a fevered body, it points towards his next direction.

In 1965, Ayler formed a group with his brother Don on trumpet and Charles Tyler on alto sax. The principal change came in the source material, which seemed to come from some archive of fusty old tunes. Sometimes the group will just play the melodies, as belligerent, blustering recitalists: the vernacular was weirdly out of step with the other jazz in Ayler’s hearing, and only he could have done it. Bells, released as a one-sided record for ESP, is a compelling example of this group in concert. Ayler had already attempted a major work with other horns in the massive New York Ear And Eye Control, commissioned for a film by moviemaker Michael Snow. Ayler asserts himself through the near-chaos by force of personality. In the film, where the soundtrack suddenly booms in after several minutes of silence, the music accompanies a series of static images until the closing sequence, where Snow films each member of the group talking in close-up while their playing thunders on.

As powerful as the music of 1965-66 was, with the European tour which included the violinist Michael Sampson, and an American recording with the young Ronald Shannon Jackson, the impact of Ayler’s earlier music had already begun to dissipate. Earlier! Only two years separates Spiritual Unity from the concerts in Lorrach/Paris 1966. In that period, with Coleman and Taylor largely absent from the studios, much debate centred on Albert Ayler. But it was going on in a tiny margin of the music. Unlike John Coltrane, who had studied and learned from Albert’s manner, Ayler was struggling as much as any stranded bebopper under the onslaught of rock.

That may account for the way his music turned, a notorious change at the time, but one which now seems less amazing, given the ongoing fusions of the last two decades. New Grass and its following music stuck him with what Ian Carr calls “a nice little blues/gospel backing band”. The music’s brief tracks and vocals slip past harmlessly. But when you reflect on what the same man was doing a few years before, it seems absurd.

IT’S A long time ago now. Albert Ayler’s death in February 1970 seems to have been at his own hand, his body found floating in the Hudson River. As swiftly as his career ran its course, so did his philosophy move towards the end. “It’s not about notes any more, it’s about feelings,” he said at the beginning. “All my music is purely music of love.” “I really meditate on the universal thoughts, I can’t be restricted to an earthly plane.” “I must communicate with their spirit that comes within the soul and the heart.” “I saw in a vision the new Earth built by God coming out of heaven.”

There’s danger in seeing him as a mystic, as mystifying as his music could be. Ronald Shannon Jackson remembers him carrying an aura around with him, an indefinite sense of otherness. But if we see him as some kind of Black shaman, a man “speaking in tongues”, as Nat Hentoff described Coltrane and Sanders, we marginalise him again, into the eccentric, exotic limbo which too much difficult Black music has been conveniently sent to.

How else to appreciate him? As harbinger of revolutionary anger? As much as Ayler embodies the zeal of the new jazz of the 60s, he is set apart from most of his contemporaries by the lonely force of his vision. The easy interpretation of his music is “rage”, a description often used by such different personalities as John Coltrane and Archie Shepp. But the message of Spiritual Unity isn’t so easily expelled. It’s a turmoil of communications.

The vividness of that music is undiminished. People have screamed through saxophones ever since without getting to the grain of Ayler’s heart and mind. He was the most pragmatic of jazz artists: “Never try to figure out what happens, because you will never get the true message.” That is rashly taken advice, but at one level it suggests a way to understand Ayler’s music. Ever since he first appeared, people have tried to explain him away. Maybe he does reach back into the oldest, deepest roots of the music. But he gathered and expressed those echoes with a force and purpose which were and are unswervingly modern. It has always been held against him. He deliberately revived nothing of the jazz past; maybe that’s why, in this revivalist era, he is slipping further into neglect, his challenge unanswered.

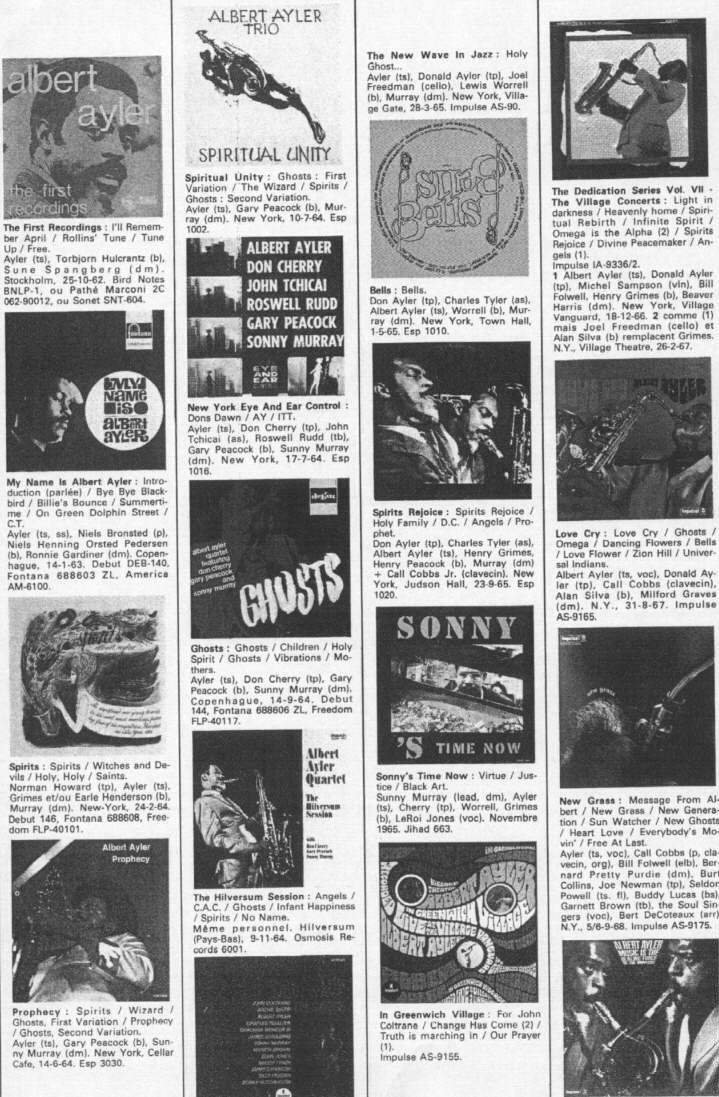

RECORDS

My Name Is Albert Ayler (Fantasy)

Spiritual Unity (ESP)

New York Ear And Eye Control (ESP)

Witches And Devils (Arista Freedom)

The Hilversum Session (Osmosis)

Spirits Rejoice (ESP)

Bells (ESP)

Lorrach/Parish 1966 (hat ART)

In Greenwich Village (Impulse)

The Village Concerts (Impulse)

New Grass (Impulse)

Love Cry (Impulse)

RICHARD COOK

*

Next: Articles 10 ()

or back to Articles main menu

|

|

|

|

Home Biography Discography The Music Archives Links What’s New Site Search

|

|