|

|

|

|

|

Concerts 4

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cleveland, 4 February 1967

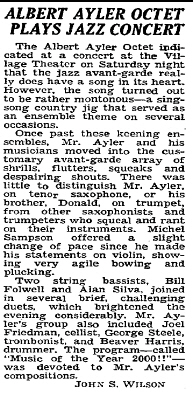

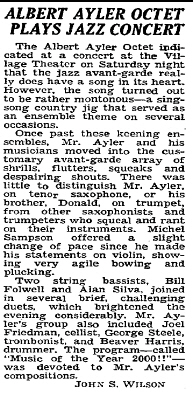

Village Theater, New York, 25 February 1967

Newport Jazz Festival, 30 June 1967

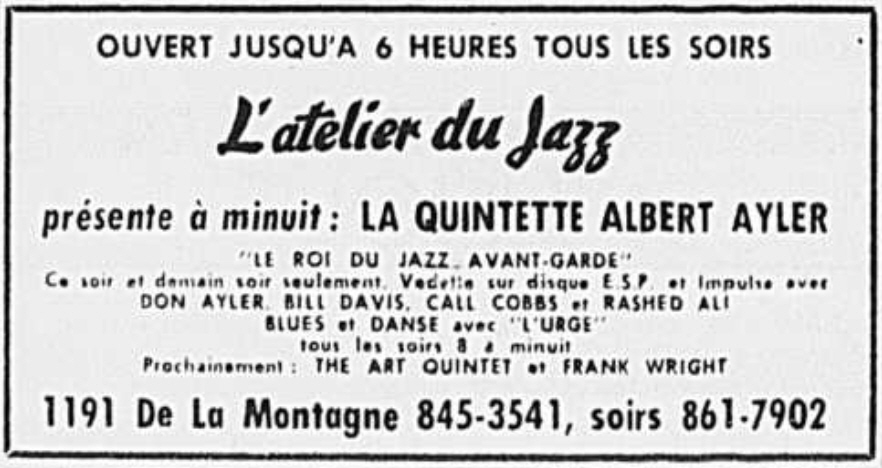

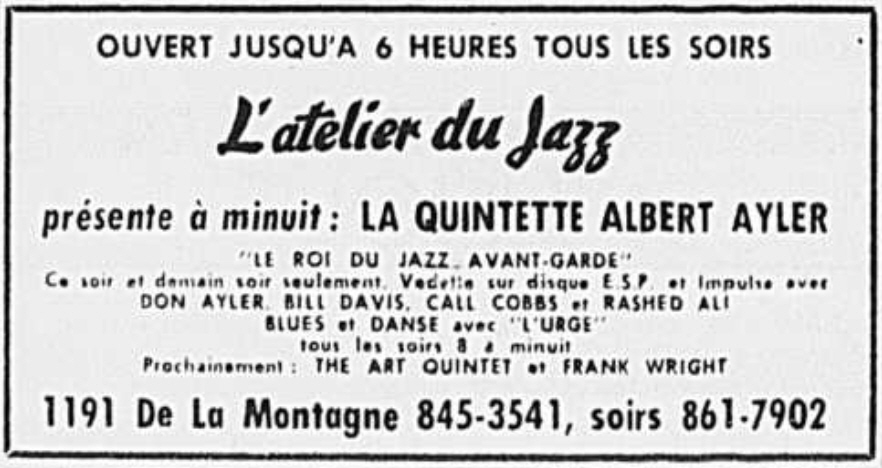

L’ Atelier de Jazz, Montreal, September 1967

Second Buffalo Festival of the Arts Today, 9 March 1968

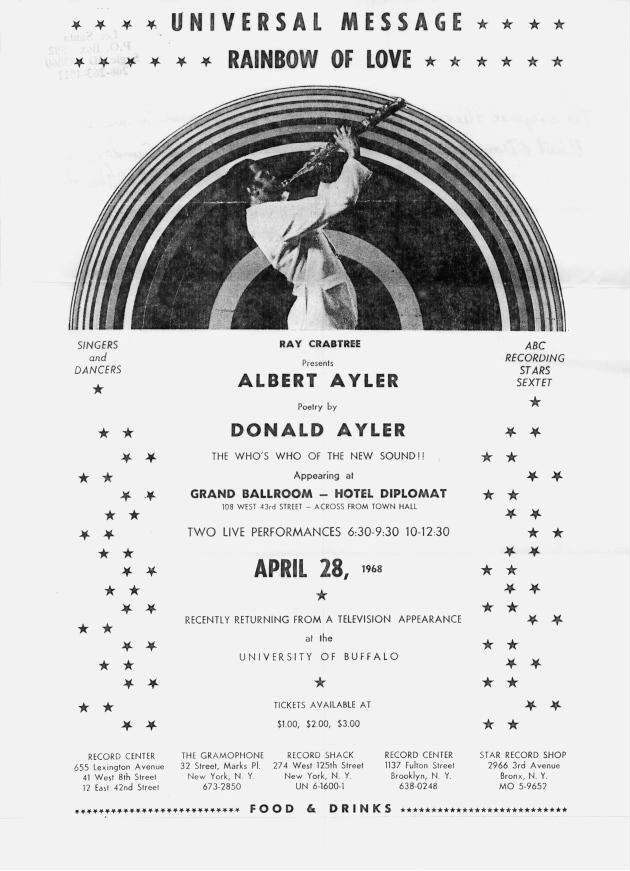

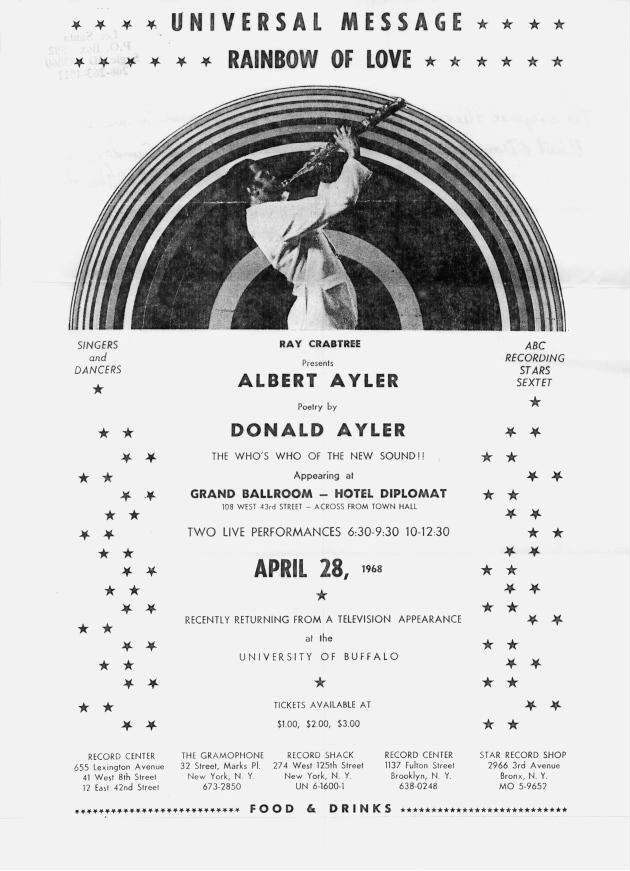

Hotel Diplomat, New York, 28 April 1968

Café au Go Go, New York, July 1968

Slugs’, New York, 21 September 1968

Fondation Maeght, St. Paul de Vence, France, 25 and 27 July 1970

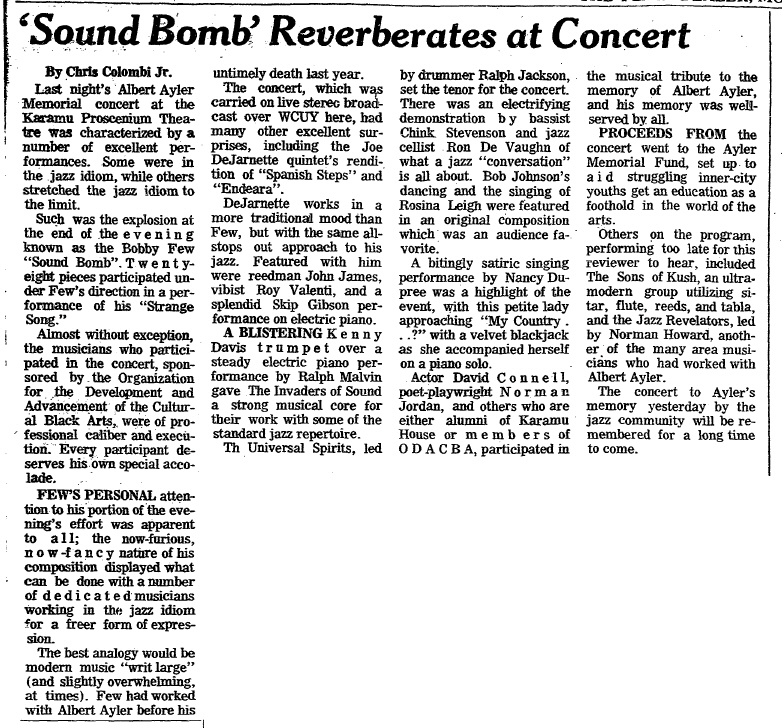

Albert Ayler Memorial Concert, Karamu House, Cleveland, 11 April 1971

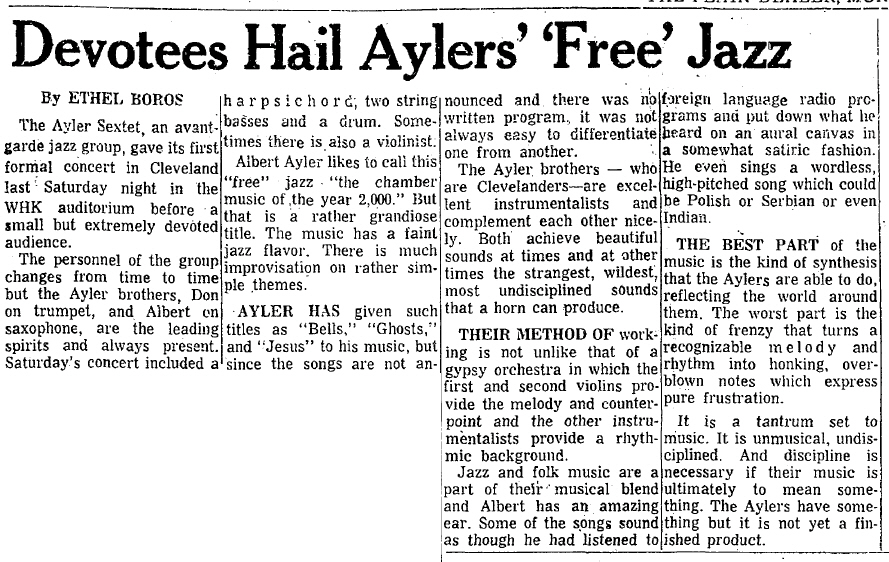

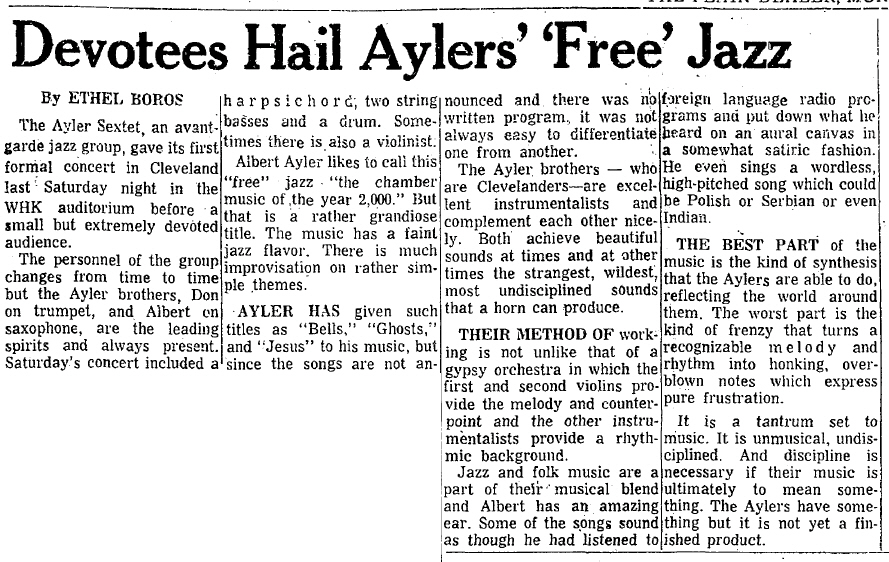

Cleveland, 4 February 1967

Cleveland Plain Dealer (6 February, 1967, p. 19)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Coda (May, 1967, p. 34)

The Albert Ayler Sextet in Concert - Cleveland - February 4, 1967

Nothing really went right for the concert. Local radio stations were not very co-operative in featuring announcements, though the performance was for the benefit of the local Music School Settlement and all sorts of free advertising is given to other less artistic and valuable functions. One of the newspapers did print an interview with Albert and Don which was originally to have been done a year ago before their last Cleveland appearance. This article was typically uninformed, but its tone was favorable. In addition, the original date set for the concert had to be changed in order to eliminate conflict with a celebration for football hero Jim Brown.

But the greatest disappointment for me, in looking over the audience in an auditorium that accomodates 1400 was the paucity of people - only about 100 dragged themselves away from the television sets or white blues singer John Hammond or whatever kept the many who told me they would be there - away. And there was publicity at surrounding colleges such as Ann Arbor and Detroit.

The problems didn’t end here. Albert originally wanted Henry Grimes and, of course, violinist Michel Samson, who has been working with him since the last appearance in Cleveland, where they met.

The group finally crystalized with William Folwell (bass), William “Beaver” Harris (drums), Call Cobbs Jr. (harpsichord), and Clyde Shy (bass) added to replace Samson.

Albert and Don, along with Shy and Harris played a concert at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, the night before and received three standing ovations from over 600 students. This again suggests the very real possibilities for the New Music on college campuses. The Andrew Hill concert in Ann Arbor last month was also reasonably well attended considering certain problems involved there.

With Samson unable to join the others in Cleveland, the sound of the sextet was noticeably thinner than tapes of recent European performances and a soon to be released afternoon at the Village Vanguard. Poor amplification did not allow much of the basses or harpsichord to be heard, so the complete textures so necessary to an understanding and appreciation of Ayler’s concept were missing. But the love that Albert generates through his songs can overcome even these difficulties.

Bill Folwell is a young bassist who was one of the original members of the UNI trio with Perry Robinson and Tom Price (see Henry Grimes, “The Call” ESP 1026). Henry Grimes is often a replacement. Folwell was unable to appear at Antioch the night before because of another interest. He was acting in an Arthur Miller play in Brooklyn. William “Beaver” Harris is a former member of the Archie Shepp Quartet and plays a lot of drums. He again demonstrated how important the percussion is to free music. As Larry Rutter wrote in Guerilla in reference to Coltrane’s music: “Drummer is the soloist/ Horns are the rhythm. . .”

Clyde Shy, the other bassist, is an old friend of Don’s who played in the group at La Cave last year and also at Antioch, taking Folwell’s place. In Cleveland he displayed his unusual approach to playing. Sometimes he used the instrument like a guitar, fingering and playing three or four strings at once, building up a frenzy of sounds.

As part of a bow to the older generation in the avant-garde, Call Cobbs Jr. was included playing a harpsichord supplied by the music settlement. Cobbs has had a memorable career but not much attention. He was an accompanist to Billie Holiday in 1936, and played in the bands of Johnny Hodges and Lucky Millinder among others. His style now includes the free use of chords outside of a harmonic context and a flurry of notes ringing beyond the chords.

I was given a list of songs numbering 12, which I read to the audience, but it seemed that only about six or seven were played and one (most interesting?) was repeated. Bells found its way in, as did Angels and Spirits Rejoice, may run together into a concerto of Ayler’s “variations on a theme” of folk and simplicity. The new song that stood out from all the rest was entitled All. Albert, his face screwed up with tension and suffering cried into the microphone, uttering sounds of vocal anguish from the roots of his soul. Don played a simple line which along with Beaver Harris’ percussion figures produced memories of certain movies featuring an African locale - Tarzan, and all that. This song (?) was done twice to the small but appreciative audience including the usual sampling of musicians, hippies, and even a few teeny-boppers (who maintained their cool for two and a half hours! !).

Perhaps it was the size of the hall or the small audience, but somehow the overall musical performance seemed quieter, less furious, less peaceful, than it has been before. Perhaps there will now be a period of adjustment, before the next development in Ayler’s music, which has gone through several stages. The development is closely connected, too, with Albert’s co-conspirators. Their personal movement and direction affects his approaches though he is still very much the leader and innovator.

Now, justly, some attention is being given to Ayler and there is the certainty of recording for a major record label and thus keeping a group together, as the number of gigs also increases.

Ayler’s music may now go into an incubation period where current ideas will be refined and new ideas generated.

- Jon Goldman

*

Village Theatre, New York, 25 February 1967

The New York Times (27 February, 1967, p. 32)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Village Voice (9 March, 1967, p. 16)

SPACE FRIENDS

by Michael Zwerin

Public relations has come to the avant-garde. Last week, I received two press releases in the mail. The first, under the letterhead, “The Ornette Coleman Trio—Ornette Coleman, violin, alto and tenor saxophone, trumpet; David Izenzon, bass; Charles Moffett, drums,” announced a “major presentation of the current season. The Ornette Coleman trio will appear in a joint concert with the Philadelphia Woodwind Quintet …at the Village Theatre on March 17.” The other proclaiming “For Immediate Release—from the New Music Feature Service,” invited me to a concert, also at the Village Theatre, on February 25. It was signed, via Xeroxography, “Albert Ayler.”

I went. Public relations, however, ended with the release because the concert looked like a total economic disaster. The theatre was maybe 10 per cent filled and a good deal of those seemed to be the Ayler family. The 25th was a very cold night and the prices were an absolutely frigid $3, $4, and $5. There had been little advertising other than the posters in front of the theatre, which has a capacity of about 2500. Whoever booked it was an optimist with a poor memory because only two months ago, when Ayler played the Village Vanguard, even that little room was far from packed. Audiences seem to stay away from Albert Ayler—a shy, sad-looking little man who has something to say.

The Albert Ayler Octet—Albert Ayler, alto and tenor saxophone; Donald Ayler, trumpet; Michel Sampson, violin; Beaver Harris, drums; Bill Folwell and Alan Silva, basses; Joel Friedman, cello; and Call Cobbs, harpsichord. Beforehand, in the lobby, Cobbs said he wasn’t playing because he had just found out there was no harpsichord in the place. “The music wouldn’t sound right on a piano,” he explained. So strike him, and add George Steele on trombone.

Also add Mary Parks on MC—an avant-garde chick. “Good—evening—space friends,” she said, her golden gown sparkling reflections no doubt from Venus, “tonight—we—will—hear a—concent—of—music—of the—year two—thousand.” With free punctuation she got the concert started 45 minutes late, not apologizing for the delay either. I thought of John Cage’s line about “the importance of being on time for anyone involved with the art of music.” But there’s a logical unreality to Albert’s music—kind of like a Ray Bradbury story—which seems to penetrate people even before he starts playing and the waiting was perfectly okay with everybody.

The tunes, all written by Albert, have names like “Light in Darkness,” “Heavenly Home,” “Spirits Rebel,” and “Truth is Marching In.” They are fiercely tonal, resembling primitive marches or folk songs, and use only three chords, if that many. Improvisation is abstract, spaced by recapitulation of the theme, usually played Germanically by Don Ayler’s trumpet along with a Liszt - cadenza - gone-wild on Sampson’s fiddle. Albert solos most of the time—on some tunes the others do not play at all other than behind him or on the ensembles.

Scot LaFaro revolutionized the jazz bass before he was killed in an automobile accident in the late ‘50s. Instead of just walking , he played swift, complex, melodic obligatos and since then many bass players have delusions of violins. They began using the bow more often and, whether arco or pizzicato, forever lean way over the instrument, both hands near the bridge, eeking the most unlikely harmonics from their instrument. Truly astounding. The only trouble is that, with the increased importance of percussion in the new jazz, the audience usually can’t hear their cascades of notes. At the Village Theatre, though, the trouble was stupid balance, unfortunately common with the avant-garde, because Beaver Harris is one of the better free drummers, keeping a pulse, no matter how abstractly, and keeping it with sensible dynamics.

Anyway, Folwell and Silva made a hell of a visual impression, scooting all over their instruments. I’m pretty sure they were playing very impressive stuff. As a matter of fact, a couple of duets between them, with everybody else tacited, were very lovely and exciting. And one tune featured Albert plus only the cello and two basses. It was cloud-like and dewy music. Albert, who did not squeak on this one, was brilliant in his abstractions, instinct supplying all of the criteria needed. And the three strings were empathetic to perfection.

Now, about Albert’s squeaks … Squeaking is nothing new of course. Illinois Jacquet and Flip Phillips did that years ago. It’s a way of transmitting energy—but it’s too easy a way and I mistrust it. Besides, it hurts my ears. Albert’s squeaking is the low-point of his playing. He starts doing it without continuity and stops abruptly without form—an insert, out of context. Few tenor players can get around up there as he can, but if he wants to hear those sounds, why not take up the piccolo or something.

Donald Ayler’s trumpet playing impresses me as being pure chance—no choice—a random combination of fast-flipping valves and embouchure adjustments. Every solo sounds alike. He rarely holds a sustained note. When he does, however, a pleasant sound comes out (I mean that as a compliment). More of that would have been nice.

Albert’s music is strangely warm and loving. The freneticism I once minded so much seems less pronounced now than two years ago. Maybe I’m better tuned to him—or possibly he has matured some. Either way, I was wrapped up in the music and stayed till the end of his concert, something I’ve never wanted to do before.

But without more artistic handling, Albert will continue to be only the obscure underground hero he now is. That’s a shame too, because, given the chance to hear it, a lot of people could find his music important.

*

Down Beat (18 May, 1967 - pp. 24-25)

Albert Ayler

Village Theater, New York City

Personnel: Donald Ayler, trumpet; George Steele, trombone; Albert Ayler, tenor and alto saxophones; Michel Sampson, violin, viola; Joel Friedman, cello; William Folwell, Alan Silva, basses; William (Beaver) Harris, drums.

This concert was the first time I heard the Ayler brothers in person.

Before going, I reread the interview with the Aylers that Nat Hentoff did (DB, Nov. 17, 1966) because I wanted to check the two major impressions I’d had when I first read the article: l, the Aylers had been unusually articulate about what they were trying to do musically, and 2, they both expressed an interest in, and a knowledge of, New Orleans jazz. The few times I’d heard them perform on records had not led me to believe that they knew where they were going or had ever heard any jazz other than their own.

A chance to share either revelation or misery with someone else became possible when an artist, Phil Featheringill, agreed to go with me. (Older jazz fans will recall that Featheringill once operated a jazz record shop in Chicago and had his own label, Session, during the ’40s.)

Featheringill and I, jazz fans whose involvement predates the swing era, have always had a similar feeling about old and new jazz. In the midst of the moldy fig v. bopper controversy, we didn’t take sides—to us, an essential of jazz was the freedom it allowed a creative artist to express himself now, the way it is.

After hearing Ayler, we still agreed.

The group had a valid “sound” of its own. It’s still experimental, far from perfect, and sometimes tedious (as in this concert’s overlong performance of, I assume, Truth Is Marching In), but the over-all feeling we both had was that we had experienced moments of high stimulation and excitement.

I recalled the comments made by the brothers during the aforesaid interview. “Don’t focus on the notes,” said Don in explaining how to listen to the music.

“You have to relate sound to sound inside the music and try to listen to everything together,” Albert added.

In this connection a curious thing happened. While the group was playing Light in Darkness, Featheringill nudged me and said, “Try listening with your eyes closed.” Upon following this suggestion, I began to understand what Don AyIer meant when he said, “Follow the sound, the pitches, the colors. You have to watch them move.”

The entire program featured Ayler music. Printed sheets distributed to the listeners listed 10 compositions by Albert and three by Don, but only eight were played. Since no announcements were made, I’m not sure what the titles were, but for the record, Albert’s numbers listed were Jesus, Light in Darkness, Change Has Come, Heavenly Home, Space Race, Ghost!!, Spirits Rebel, Truth Is Marching In, Passing Through, and Divine Peace Maker; Don’s were Our Prayer, Spiritual Love, and Peace.

Two-thirds of the concert was actually performed by a septet. The harpsichord player, Call Cobbs, listed on the program, failed to appear. For the last three numbers, trombonist Steele joined the group.

Absent from the music was the nihilistic impulsiveness that has been saxophonist Ayler’s on some of his recordings. His harsh sounds are being replaced by a much more lyrical approach. His brother, with whom he is in close musical alliance, performs with thought waves that emulate, but also offer contrast to, Albert’s playing.

But the most significant facet of Albert’s current group is the rapport and inspiration between the horns and the strings. Albert is able to achieve a saxophone timbre that is near a violin’s.

Sampson is a young Dutch violinist who joined the group last summer. He is a classically trained musician and was a soloist with the Cleveland Symphony Orchestra before his current association with Ayler. His work is especially effective on the viola, an instrument tuned a fifth lower than the violin. Sampson’s best playing came in duets with the horns.

There also were fascinating improvised solos by cellist Friedman.

Albert used two basses, and when he was not soloing, he seemed to devote his time listening closely, with an appreciative smile, to the bass duets. Bassist Folwell, like Sampson, is a classical player. He played almost exclusively arco, while the other bass player, Silva, alternated pizzicato and bowing. Rarely have I been as intrigued by the use of strings in a jazz context; Ayler’s music somehow seems right for their use.

Drummer Harris, who has played frequently with Archie Shepp, has been with the Aylers for several months. Although he is one of the new drummers of the Milford Graves-Sunny Murray school, he amazed Featheringill and me by playing in the swing idiom on his one solo.

As expected, Albert played frequently in the upper register of both tenor and alto—Featheringill remarked, “We used to call those ‘freak tones’”—but the result was not jarring: he didn’t shriek. One got the impression that the unfamiliar sounds could become quite pleasant when one is used to them through exposure. Only a saxophonist with mastery of his instrument could possibly play in this register with the control evidenced by Ayler.

Some of the group’s work is based directly on the traditional polyphony of the old New Orleans brass bands. The front line of the two brothers and violinist Sampson playing collectively is apt to cause a listener to disbelieve his ears for a moment and think he is hearing a New Orleans parade band.

In fact, the sources for Ayler’s music are likely to come from almost anywhere. There was Eastern European folk- dance music (polkas and schottisches) and mariachi music, as well as the marching band sound.

It was encouraging to a couple of old-time jazz listeners to know that where it’s at is still within reach.

—George Hoefer

*

Coda (May 1967)

. . .

Two concerts took place in the Village Theatre, on New York’s Lower East Side. Albert Ayler played a concert on February 25. His group varied from quartet to octet. Most of the program was played with the familiar combination, brother Don on trumpet, Beaver Harris on drums, Michel Sampson on violin and Bill Folwell and Alan Silva on basses. Again, the medley of catchy Ayler tunes where Ayler’s own solos on tenor and now also alto saxophone, made the biggest impression. Actually, only Sampson, and in a more restricted sense also Harris, seem an adequate match for Ayler’s force. Duets between tenor and violin were exciting, sometimes delicate, sometimes flamboyant. Don Ayler’s trumpet is strong, but sometimes I wish he would be more delicate. His imagination seems to be continually stretching in the same direction.

Actually, we heard some of the most interesting music of the evening when the group changed to a quartet with the two bass players and Joel Freedman on cello. Ayler’s force is not primarily in overall concepts of form or conducive leadership, and I thought it strange that he seemed better able to create music of a logical form and musical expression in this combination rather than in the group he works with most of the time. I should mention the beautiful bowed duets between Silva and Folwell.

At the end was a piece involving all the afore-mentioned musicians plus an unannounced trombone player, whom I was not able to hear because of lack of amplification. A high point of this last work was a three-voiced improvisation between Ayler, Freedman and Sampson where it was again evident how well a combination works when Ayler contributes his dynamic force and Freedman and Sampson their very precise and direct following of Ayler’s musical line of thought.

. . .

- Elisabeth van der Mei

*

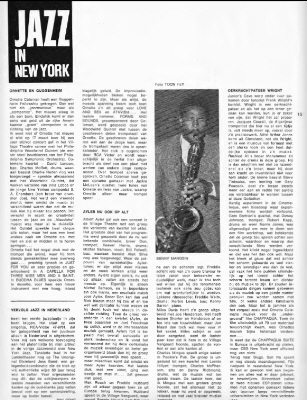

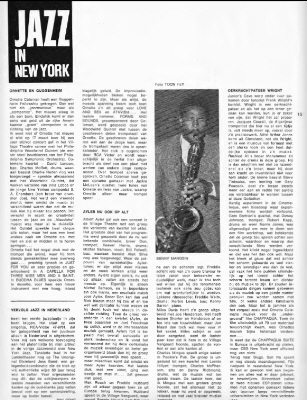

Jazzwereld (No. 13, July-August 1967, p.15)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Translation courtesy of Kees Hazevoet:

Jazz in New York

By Frens van der Mei

Ayler now also on alto

Albert Ayler also gave a concert at the Village Theatre [earlier in the review, Van der Mei writes about an Ornette Coleman concert at the same premises; KH], with a group that varied from a quartet to an octet. The main part of the program was played by the by now well-known combination, brother Don, trumpet, Beaver Harris, drums, Michel Samson, violin, Bill Folwell, bass, to which bassist Alan Silva was added. Again the potpourri of catchy Ayler-tunes; there are always new ones and the old always sound different. As always, Ayler’s own solos, now also on alto, are the most striking. Properly speaking, only Michel Samson, and to a lesser degree also Harris, is a musical match for Ayler. Although brother Don can surely blow loud, he could at times be a bit more subtle, as his thinking is nearly always going in the same direction. When the group changed into a quartet (Ayler, the two bassists and Joel Freedman on cello), the music became more interesting. Ayler’s forte certainly isn’t overall conception and strong leadership and I found it surprising that the music of this combination showed to be more lively and better organized than with his usual group….but perhaps that was because we heard more Ayler. The last piece, with an octet, wasn’t very successful….it just didn’t fit well.

*

Newport Jazz Festival, 30 June 1967

The New York Times (2 July, 1967 - p.34)

. . .

The last two groups in this brief historical review—the Modern Jazz Quartet and the Albert Ayler Quintet—were sufficiently contemporary to perform simply as they are. Mr. Ayler, an avant-garde saxophonist, who mixes odd, off-key melody and simple little chants with violently discordant explosions, brought the program around full cycle.

There were strong points of similarity between the playing of his group and that of Olatunji’s African percussion ensemble (which included three saxophones and a trumpet), which opened the evening with performances intended to suggest one of the root sources of jazz. Mr. Olatunji’s primitivism was so sophisticated and Mr. Ayler’s sophistication was so primitive that they seemed to occupy the same piece of ground in the jazz spectrum.

(from a review of the Newport Festival by JOHN S. WILSON)

*

Down Beat (Vol. 34, No. 16, 10 August, 1967)

THE UNDISGUISED NEW THING was represented solely by the Albert Ayler quintet. The leader, playing both tenor, alto, and soprano saxophones, is an original—there can be no doubt that he plays the way he does because he feels it.

The group sounded at times like a Salvation Army band on LSD, with Michel Sampson’s expert, sophisticated, wholly non-jazz fiddling adding a diabolical note. They closed the Friday night show with a set unusually succinct and varied (in terms of selections played, at least) for an avant-garde group. Sincerity, alas, has never yet sufficed to make notable art.

(extract from a review of the Newport Jazz Festival by

DAN MORGENSTERN and IRA GITLER)

*

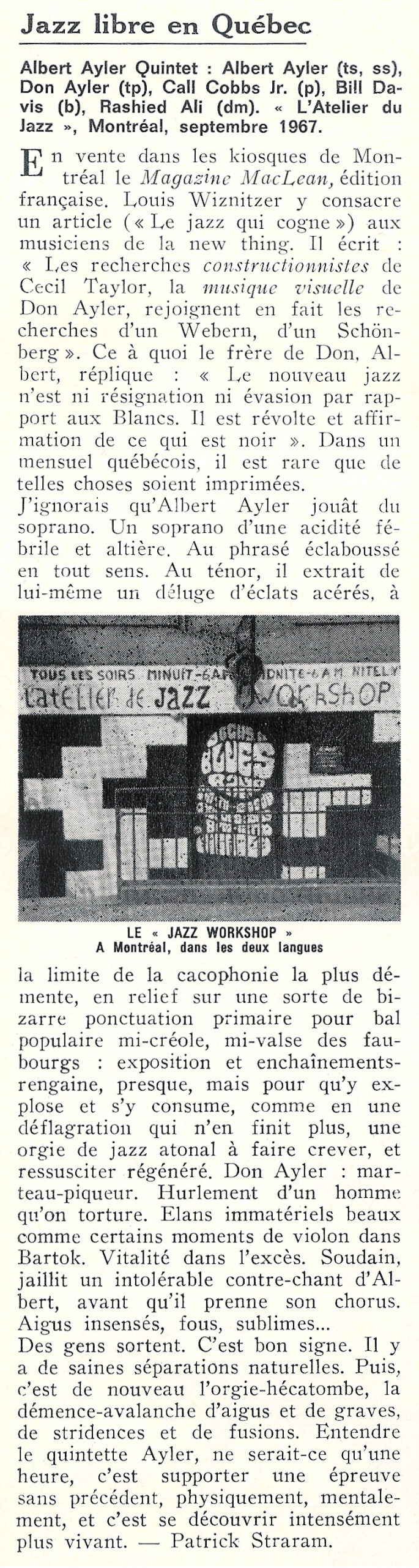

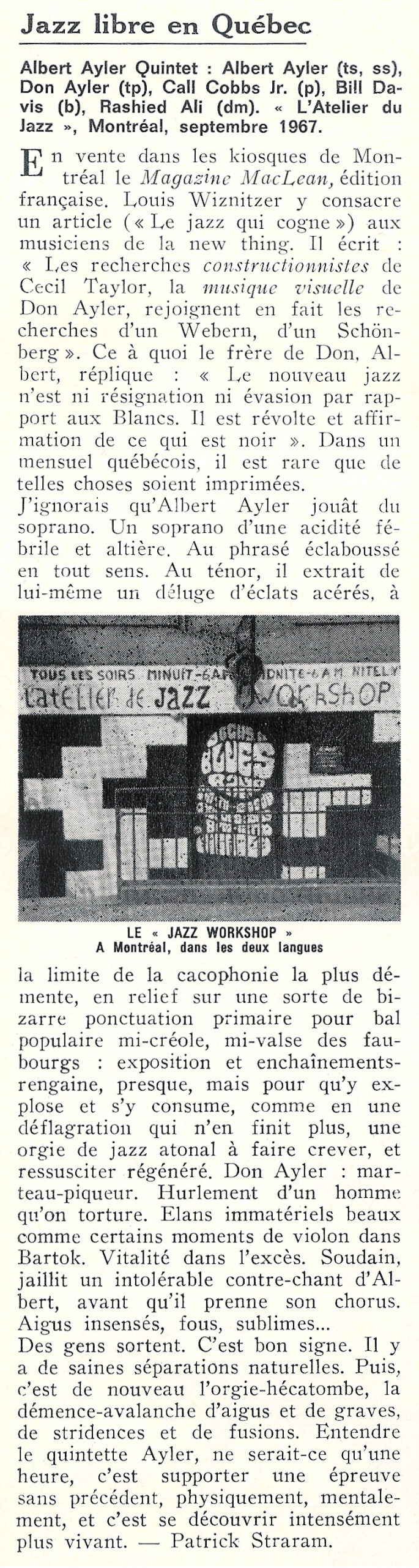

L’ Atelier du Jazz, Montreal, September 1967

La Presse (Montreal) (Saturday, 26 August, 1967 - p.27)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Le Devoir (Montreal) (29 August, 1967 - p.10)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

La Presse (Montreal) (2 September, 1967 - p.34)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jazz Magazine (November 1967, pp.12-13)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Coda (No. 272, March/ April 1997)

Breakfast in Montreal: Albert Ayler in Canada

by Stuart Broomer

In the late summer of 1967, I went with my band of the day from Toronto to Montreal where we were to play in a Michael Snow performance at Expo '67, Canada's World's Fair. We arrived at night, the day before our accommodations in a vacant college dorm would be available. One band member had a friend in the city, and we arrived late on his doorstep. It was going to be crowded, with five of us sleeping on the floor in one small room. Imagining the sleeplessness before me, I decided to go exploring, thinking that just walking around somewhere unfamiliar would be more fun than trying not to wake other people.

With the approximate address of a club I knew might have interesting music, I set out. I didn't know what I'd find, but it was one of those rare moments that happen only in youth. The band that was playing was Albert Ayler's.

Now that would be one kind of surprise, maybe even better, for someone who'd never heard of Ayler, but at the time I was convinced that he was among the most important musicians on the planet. In the previous two years I'd written a couple of pieces to that effect for Coda, a long review of Spiritual Unity and an article on all his records available at the time. His playing had contributed much to my thinking about music. I'd heard some of his key sidemen live -- Sunny Murray, Henry Grimes, Charles Tyler -- but I'd heard Ayler only on record. So it was a special instant, when even the fear of insomnia seemed in some special synch with the universe, one of those rare and generous moments when the world feels like it's been staged just for you.

I can still feel my surprise at seeing his name on a hand-lettered sign on the street, but my recollection of the club itself is sketchier. It was an after-hours coffee house, a few steps below street level. The band was already playing, the music seeping outside, but when I went through the door Ayler's tenor hit like a wall, not violence or anger or any of those things, but a wall of impossible sweetness. At midnight there was only a scattering of people there, and I sat down close to the stage.

The band was a quintet with Ayler's brother Don on trumpet and Call Cobbs playing an apartment-size piano. I recognized Rasheid Ali on drums. I'd met him a year before when I'd gone to Detroit to hear Coltrane. The bass player, unfamiliar to me by both sight and sound, turned out to be one I'd never heard, or heard of, either before or since, named, I'm almost positive, Bill (not Steve, not Art, and not Richard) Davis. I'm not sure now if the band didn't outnumber the audience even at the start of the night, when the club was as crowded as I would see it.

The music was extraordinary. I know I'd heard better Ayler bands on records, but Ayler's sound was one of the great musical truths, so huge and bright and various and alive, the most fully human -- and humanly full -- sound I've ever heard from a musical instrument. He was playing alto, too, that night, with an incredibly broad, almost cavernous tone. Don Ayler, it's true, shared few of his brother's talents, but he played trumpet as if everything else had been sacrificed to sheer sound, a great metallic blaring that seemed to carve the air into blocks then shunt them around that low-ceilinged room. There's much to be said for a musical conception large enough to include very different levels of skill, and Ayler's conception was one of those. I've never heard a recording that did justice to the parade band sound of the brothers playing Albert's simple themes together, the concordances and divergences tangible in the air.

I introduced myself between sets. Ayler knew the articles I'd written about him and was pleased by them. He thought that people could hear the music better "outside the empire." Coltrane had died only a few weeks before, and his presence could be felt in the way Albert and Rashied played that night (the loss had not yet come to mean all that it would, though, for Coltrane was a principal link between the art and the business of jazz). Albert told me that the last time they'd talked, Coltrane had declared himself the father, Pharoah Sanders the son, and Albert the holy ghost. It was a kind of statement that could send me running, but from Ayler it seemed plausible. There was no arrogance in it, only his wonder at the scale of the music he was playing. It was a way of finding language to give the music its rightful dimension. He had a sense of his own ascendancy, telling me confidently and modestly, as if the avatar of outside were a job, that he had to keep working at it as he felt Pharoah Sanders gaining on him.

The performance ended around 4:30. By the end of the last set, I was an audience of one, something that's made it hard for me to line up ever since. We left the club and went for breakfast, the sun just coming up. It was really just a pleasant conversation, but there were things Ayler said that I remember still, and one in particular stands out.

He asked about the instrumentation of my group, and registered surprise that there was no bass player. He remarked that you had to have a bass player in New York, otherwise people would "think it was weird." It struck me then, and strikes me still, as one of the most valuable things anyone ever told me about jazz. What I felt was Ayler's resentment of the nagging, even ridiculous constraints on making music in the jazz business. Even for Ayler to hope for acceptance, it was important that the band "look like" a jazz band. It might help explain why, in his brief career, he had gone from playing with the very best bass players (Grimes, Gary Peacock) to touring and sometimes even recording with ones who mattered little to the music, or how he went from those beautiful performances with strings to what "looked like" conventional groups. That night in Montreal the band had the instrumentation of a bop quintet. This isn't to say that Ayler didn't have bands where one or even two bassists were an essential and vital element, only to say that Ayler's view of the audience required a bass player whether or not he felt any musical reason to have one.

The first important band he'd played in, Cecil Taylor's, had managed without one, but that, after all, had been in Denmark, far away from "the empire." When he recorded the first session for Love Cry within a few days of that Montreal performance, he used Alan Silva, a fine musician who played the instrument as little like a "bass" as possible. That sense of continuous constraint may have made it easier for Ayler to shift to the electric fusion settings of the later Impulse records. In a sense, perhaps, the continued presence of the veteran Cobb, who had played with Johnny Hodges and Billie Holiday, was a literal sign of jazz history, part of a complex bargain Ayler had made between his ideas of music and audience. Given that view, the electric harpsichord that Cobb played on Ayler's records may refer ambivalently to a longer musical history.

Copyright © 1999 Stuart Broomer

*

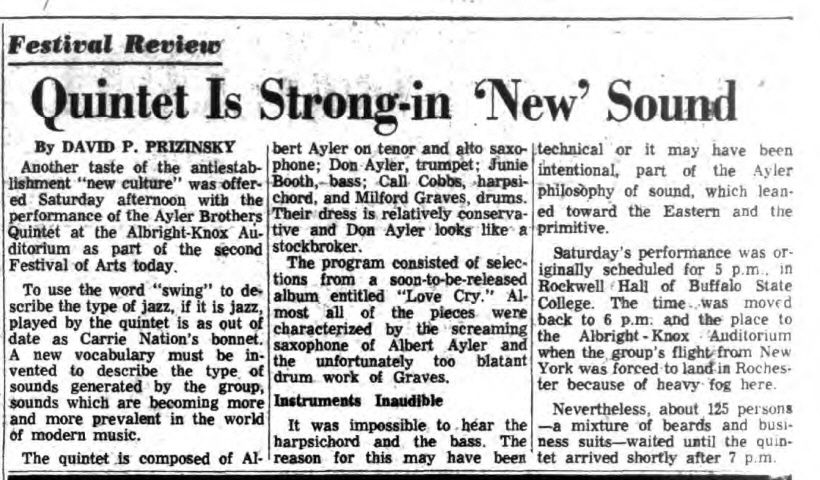

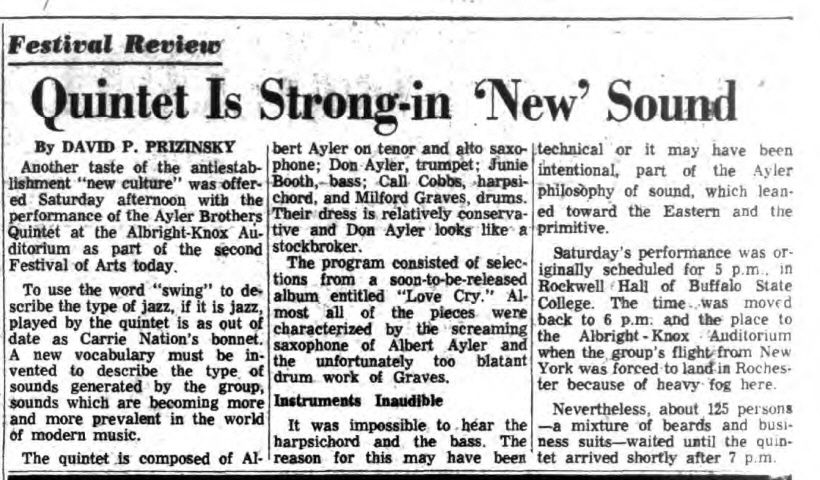

Second Buffalo Festival of the Arts Today, 9 March 1968

Buffalo Courier-Express (10 March, 1968)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hotel Diplomat, New York, 28 April, 1968

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

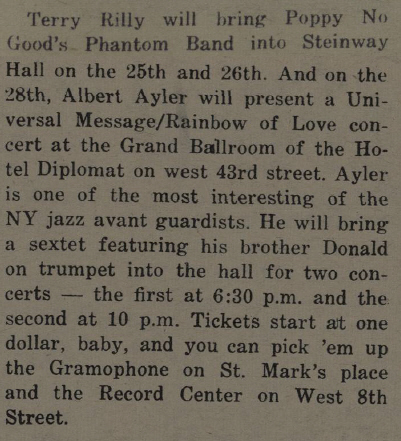

The East Village Other (Vol. 3, No. 20, April 19 - 25, 1968, p.15)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jazzwereld (No. 19, August 1968, p.19)

[Click the picture below for the full page.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Translation courtesy of Kees Hazevoet:

Jazz in New York

By Frens van der Mei

Ayler’s voices

As he never works in New York, every now and then he organizes a concert hmself, with all the difficulties that come with it. The organisation of the event didn’t go smoothly, it shouldn’t be the job of an artist, but the music was stunning. At the moment, Ayler uses many voices in his music. He had four female singers, who didn’t sing words, only sounds, incorporated in the music as instuments. Only brother Don was on stage during the entire concert.......there were three different bassists......four different drummers......who each took their turn and of whom I didn’t know anyone, all unknown musicians, who fitted in Ayler’s music in different ways. I tried to find out their names, but most of the time Albert didn’t know their name himself......”doesn’t make any difference.....they feel my music so I play with them”. And there was the Ayler magic. Said someone in the audience: “Wow, that guy only needs to play one note to get me excited”. Many melodies, almost no solos, seemingly unorganized music, which nevertheless leaves a feeling of unity in the end.

*

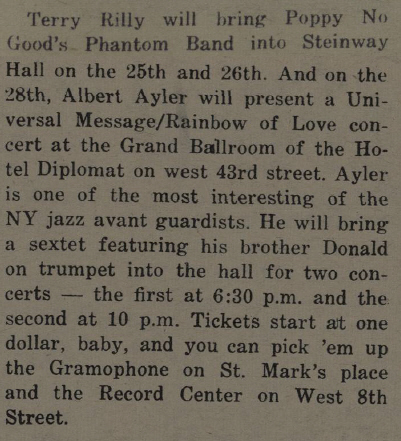

Café au Go Go, New York, July, 1968

The East Village Other (12 July, 1968 - p.13)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Coda (November/December 1968, p. 39)

. . .

Ayler . . his last gig in New York was at the Cafe A Go-Go, once an all jazz club (remember Getz Live At The Go-Go) but lately an all rock affair. Prodded by my allies in the New York underground press, urging the local pop barons to present New York’s avant garde musicians, Ayler was given a week to try his thing out . . . the result was not as glorious as I had expected . . Frankly, Ayler did not do as well as he could have, but this is mainly the fault of the combination with which he played - it was not strong enough to defend this experiment. I have told you before that it is virtually impossible, economically, to keep a group together in New York and Ayler’s choice for this occasion was not a very happy one. Call Cobbs on piano is sweet and docile but does not contribute to the excitement. Beaver Harris is too clean, too straight a drummer for Ayler and Bill Folwell is definitely not the class bassist Ayler needs, especially when Folwell insisted on playing an electric bass on which sound gradation, so important in Ayler’s music, is nearly impossible. But, as always, Ayler himself was glorious and people did get turned on to him himself and sometimes I wished he would just play alone . . . Brother Don is not in the group at the moment for reasons I could not get explained from either of them. “We just want to get away from each other for a while”, Albert said.

Don is forming his own group at the moment, which includes Noah Howard, alto; and Donald Strickland, bass clarinet. Haven’t heard them yet, but hope to soon.

. . .

- Elisabeth van der Mei

*

Jazzwereld (No. 22, February 1969, p. 11)

[Click the picture below for the full page.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Translation courtesy of Kees Hazevoet:

Jazz in New York

By Frens van der Mei

Don Ayler on alto

Don Ayler played on a Saturday afternoon [in Slugs]. That’s when people play, who club owners don’t dare to hire for a whole week. Unfortunately the organization was completely lost. Half the group didn’t show up, so I couldn’t hear the music that I had been wanting to hear for quite some time. I couldn’t verify the many stories about a fantastic new pianist and bass-clarinetist. Rashied’s brother, Mohammed Ali, was the drummer and he is just as fierce as his brother, just as energetic, in the category of exciting drummers, very super fast with the hands. Don played his piercing trumpet and I must say that it didn’t have much form. He also plays alto now and sounds like a derivative of his brother.

To make good on things, Albert Ayler was also present and as we hear so little of him, it is always a special occasion, organized or not. Albert also plays bagpipes now and the sounds he makes on it are hard to describe. Don: “It doesn’t make sense to try and keep a group together… Whenever there’s a chance to play, we’ll just play… and see what happens”. Example of a fatalistic attitude, quite common in these circles. It wasn’t total chaos, but “creative disorder” in which moments of great music alternated with utter nonsense…, but those special moments!

*

Fondation Maeght, St. Paul de Vence, France, 25 and 27 July, 1970

Jazz 70

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jazzwereld (September 1970, pp. 3-4)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

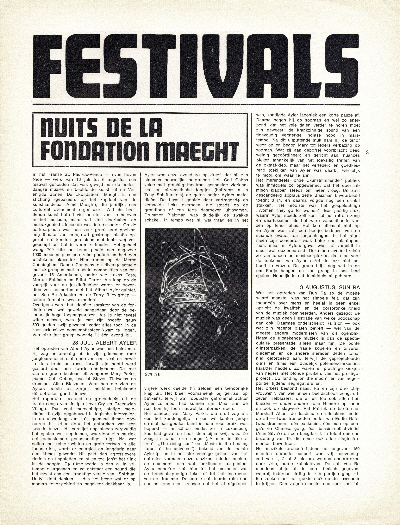

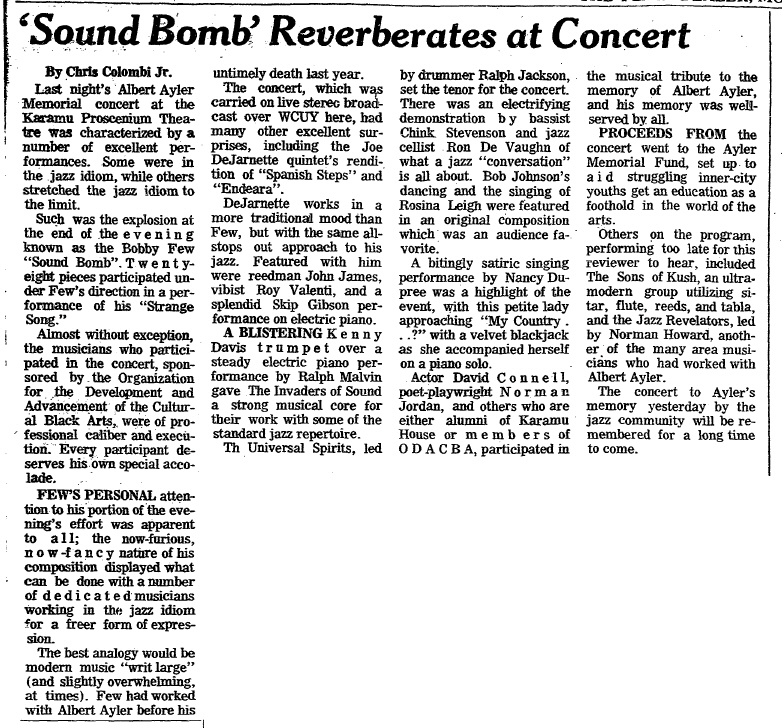

Albert Ayler Memorial Concert, Karamu House, Cleveland, 11 April, 1971

The Cleveland Press (2 April, 1971)

Who was Albert Ayler?

Bernard Lairet is a freelance writer and a knowledgeable enthusiast of jazz music.

By Bernard Lairet

Was Albert Ayler more famous than George Szell? There is a question which may well astonish most of you, for I would wager that you never heard of Albert Ayler, and I’m not a betting man.

One of Cleveland’s own, though almost unknown in his home town, he was buried quietly at Highland Park Cemetery. His body had been found in the Hudson River, New York. He was 34.

The announcement of his premature death at the height of his creativity, stunned well-informed musical circles in far distant corners of the world.

Last November, a Japanese friend showed me a luxurious Japanese magazine which had devoted a detailed study of 30 pages to Albert Ayler, and he was surprised that Cleveland and the U.S.A. neglect so many of their most prolific and most important creators.

TO AFFIRM that Ayler was more widely known than George Szell is by no means an empty wager. George Szell was, without a doubt, a most exceptional artist with remarkable qualities, and it is certainly not my intention to challenge the success of an unquestionably distinguished career.

One can nonetheless concede that Szell was without revolutionary musical genius, and was therefore probably of less significance to the long range evolution of music than was Albert Ayler.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

JAZZ GREAT? This photo of Albert Ayler appears on the inside cover of one of his albums.

EUROPEANS seem to possess a highly cultivated sense of critical analysis which is coupled with the greatest respect for jazz music. However, in the land of its origin, this musical form suffers from a regrettable lack of attention.

More than 20 well known American jazz-men (among whom are Kenny Clarke, Johnny Griffin, Art Taylor, Phil Woods) have chosen to live in Paris where, in late 1969, in a single month, a French record company recorded a series of more than 30 albums of young avant-garde American jazz musicians on a tour of Europe.

ALBERT AYLER made his recording debut in Denmark before realizing an extraordinary group of albums in the U.S.A. on the ESP and Impulse labels.

To appreciate Albert Ayler means first to ignore the barriers behind which most conventional musical ideas take refuge.

Such is the problem with which each avant-garde artist is confronted; How to gain acceptance for a work which defies the norm, one without clear reference to the classic rules?

Ayler has completely overturned many of the principles of modern music and spoken a somewhat more complex language—one which has been successively labeled free jazz, new thing, new jazz, and currently, new music.

BUT THIS LANGUAGE of his was deeply rooted in jazz and possessed an intense expressive power capable of frightening those listeners who expect music to be a simple background cushion of agreeable sounds.

Yet, during several performances in New York at which children were present, they were delighted by this music, their spirits as yet unhampered by the norm of acceptability.

There is little doubt that Albert Ayler’s music is the key to future developments. But even though it has succeeded in captivating a great part of the world, here it will be necessary to wait before all his influences become evident and enjoy total recognition.

The Organisation for the Development and Advancement of the Cultural Black Arts is seeking $5000 to start a scholarship fund in honor of Saxophonist Albert Ayler.

The money will be for musically talented, underprivileged black youths. A fund-raising concert will be held Sunday, Apr. 11, 3 p.m. at Karamu House, 2355 E. 89th St. Admission is $5, for patrons, $25.

For information call ODACBA, 621-7135 or Mrs. Ralph Jackson, 587-2478.

*

Cleveland Plain Dealer (12 April, 1971)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Cleveland Scene (22-28 April, 1971, p. 8)

jazz

By BERNARD LAIRET

Holy Week for jazz fans began Easter Sunday. At Karamu House the ODACBA sponsored Albert Ayler Memorial Program was a spectacle of extraordinary quality from which burst forth the fantastic “Bobby Few and his Sound Bomb,” 28 musicians - 5 tenors, 4 altos, 1 baritone, 4 trumpets, 1 trombone, 1 flute (electric fortunately), 5 bassists, 1 cellist, 3 drummers, 1 percussionist, 1 conga!! As the curtain opened, merely the sight of them was so impressive, even disquieting, that it aroused a “Wooh!” of stupefaction from the audience. The Sound Bomb performed only one number, a composition of Bobby’s - the vibrant “Strange Song” - articulated in three parts, with three distinct themes, simple orchestration, but producing an astoundingly rich and completely original sonority. Few was able to play only a few notes on the piano, having the orchestra to direct wherein he executed a delightful ballet of gestures.

Beginning with a gigantic crescendo of cymbals and gongs, the first theme, a slow 3/4 tempo, was quietly introduced by bowed basses, then stated by the trombone and the baritone sax. The second theme resembled a kind of ping-pong like exchange in 7/4 time between the above-mentioned instruments and the rest of the orchestra. The third was a simple chromatic ascent and descent, played in unison, at a more and more accelerated cadence, increasing gradually in force to a roar, a cataclysm opening the door to the “free” expression of the band and the soloists. Few would indicate, at irregular intervals, one of the three themes by way of a riff or point of reference. It is, of course, extremely difficult to describe the performance, all its unexpected discoveries, the unceasing variations in the level of resonance, the changes in rhythm, and especially to give an idea of the stature of the soloists. Bassist Ali Jameel, trumpeter Kenny Davis, tenor player Bob Spangler, and alto saxophonists John Abrams and Don Manuel were particularly outstanding. I have been able to follow the very rapid evolution of young Don Manuel who already shows a completely individual style reminiscent of no one, and about whom I will wager much will be said in a very few years.

Bobby Few seems to have found quite a viable vehicle which generated real enthusiasm among the participants. However when you read these lines, he will have chosen to pursue the passionate and uncertain adventure of a European tour with Frank Wright, and will not be able to continue this promising experience. Indeed, that same evening, it was with Frank Wright, Norris Jones on bass and Muhammad Ali on drums that he took part in another concert at the WHK auditorium. You may be surprised by the new techniques of the avant-garde musician - the galloping cascades of Bobby Few’s fingers across the keyboard, or the overtones, shrill harmonics, and low “honks” of Frank Wright’s saxophone. You may not immediately assimilate their new language, or may be stunned by its paroxysmal quality. But one has to be captivated by their conviction, their visible joy, and fascinated by the freshness of their inspiration.

*

Jazz Hot (No. 273, June, 1971, p. 25)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|