|

Music Is The Healing Force Of The Universe The Inconsistency of |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

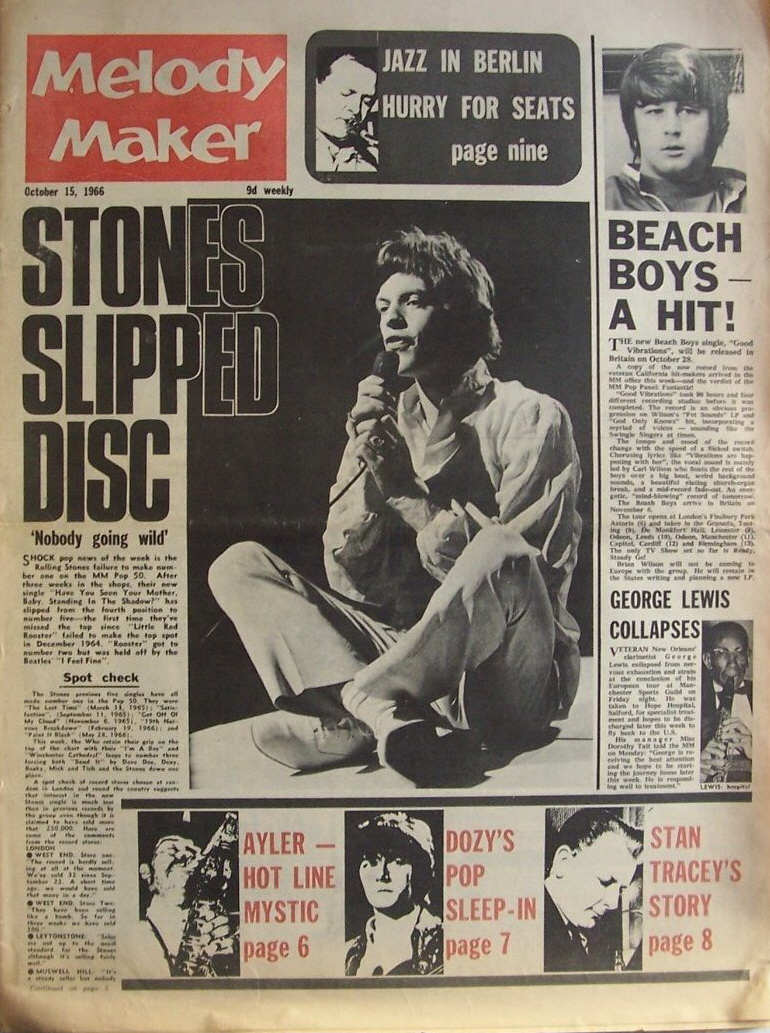

Ayler: Mystic Tenor With A Direct Hot Line To Heaven? Val Wilmer’s interview with Albert Ayler from Melody Maker, 15 October, 1966. The Truth Is Marching In Nat Hentoff’s interview with Albert and Don Ayler from Down Beat, 17 November, 1966, - pp.16-18, 40 Michel Samson: I don’t really try to play jazz - Bert Vuijsje’s interview with Michel Samson from Jazzwereld No. 11, March 1967. The Road To Freedom Daniel Caux’s interview with Albert Ayler. Originally published, as ‘My Name is... Albert Ayler’, in Chroniques de l’art vivant No. 17, February 1971, pp. 24-25 - English translation from The Wire No. 227, January 2003, pp. 38-41. Going Outside by Sunny Murray, as told to Robert Levin, from The East Village Other Vol. 5, No. 43, 22 September 1970, pp.15, 22. Sunny Murray: Interview - Spencer Weston’s interview with Sunny Murray (transcribed by Bob Rusch) from Cadence, June 1979. Bernard Stollman - The Man from 5D John Kruth’s interview with Bernard Stollman, an amended version of which Avonturen in de New Thing (Adventures in the New Thing) Rudie Kagie’s interview with Michel Samson from Jazz Bulletin 83, June, 2012. English translation by Kees Hazevoet. ___

|

|

|||

|

|||

|

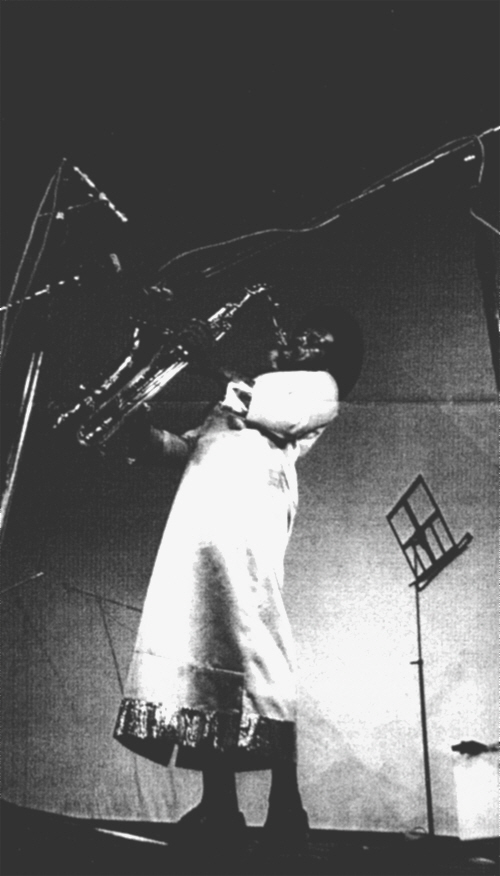

AYLER: NEW YORK VALERIE WILMER WHEN his records “Bells”, “Ghosts” and “Spirits” first hit the market with the impact of an erupting Vesuvius, Albert Ayler’s amazing tenor saxophone was variously described as being “like an electric saw buzzing” and “the ugliest sound yet to emerge from the avant garde”. Ayler, an affable 30 year old, doesn’t see it that way. _________________ SILENT SCREAM “But now it’s peaceful. It’s more like a silent scream.” __________ PEACE “That’s all I’m asking for in life and I don’t think you can ask for more than just to be alone and create from what God gives you. Because, you know,” he leaned forward confidingly, “I’m getting my lessons from God. I’ve been through all the other things and so I’m trying to find more and more peace all the time.”

*

Down Beat (17 November, 1966 - pp.16-18, 40) - USA [also available as a pdf download:: pages16-18 and page 40.]

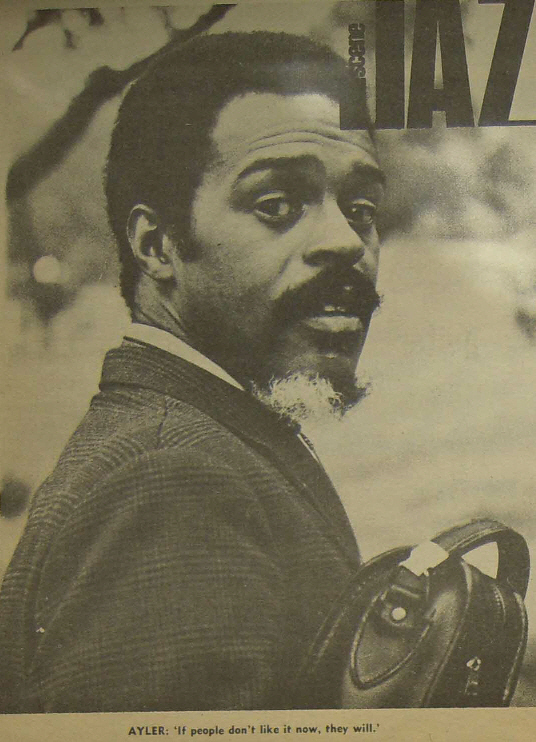

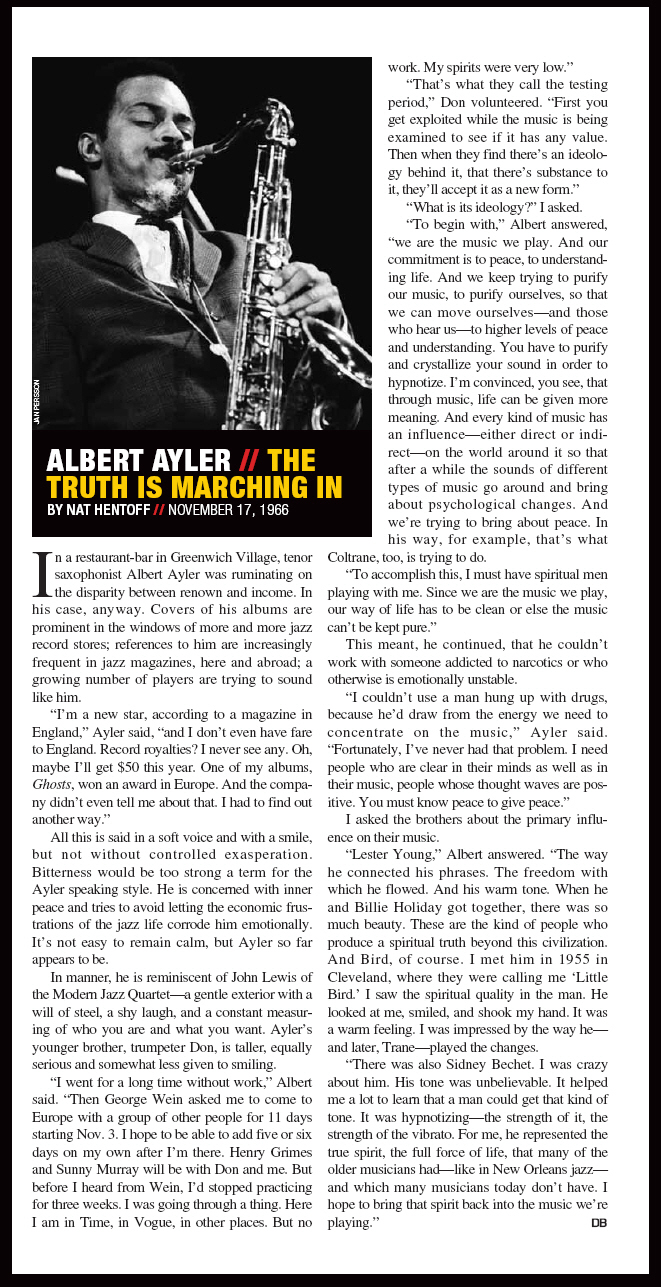

Albert Ayler - The Truth Is Marching In By Nat Hentoff

IN A RESTAURANT-BAR IN Greenwich Village, tenor saxophonist Albert Ayler was ruminating on the disparity between renown and income. In his case, anyway. Covers of his albums are prominent in the windows of more and more jazz record stores; references to him are increasingly frequent in jazz magazines, here and abroad; a growing number of players are trying to sound like him. THE ELDER AYLER brother was born in Cleveland, Ohio, July 13, 1936. DON AYLER, born in Cleveland Oct. 5, 1942, was taught alto saxophone by his father. While studying at the Cleveland Settlement, he switched to trumpet when he was about 13. *

An abridged version of this interview was also published in Downeat in May, 2009: |

|

|

*

[This interview with Michel Samson originally appeared in a Dutch magazine (.pdf available here). The following translation was kindly provided by Kees Hazevoet.]

Michel Samson: I don’t really try to play jazz By Bert Vuijsje Ornette Coleman’s concert at the Concertgebouw, October 30, 1965, had an unexpected ending. After playing alto for five numbers, Ornette took his violin and, besides David Izenzon and Charles Moffett, two other musicians joined him on stage. One of them – trumpeter Nedly Elstak – we knew, even though we didn’t expect to see him in this company. The other, a boyish violinist with the appearance of a kibbutz inhabitant, was a complete unknown to most fans in the hall. After the concert I was told that the mysterious musician’s name was Michel Samson, that he was Dutch and said to have studied with Yehudi Menuhin in Rome. A year later he was seen on the European jazz scene again, this time as a member of the Albert Ayler Quintet. During the Berliner Jazztage, I had the opportunity to talk with him for about an hour. Michel Samson was born in 1944 in Rijswijk [a small town near The Hague] and began studying the violin when he was five years old. Six years later he received a grant from the Dutch government to study in Germany. Next came studying with Yehudi Menuhin in Rome, where the composer Gian-Carlo Menotti heard him play at a festival and arranged a grant for him to study in New York with Ivan Gelamian, “the most famous pedagogue of the violin in the West”. Third stream not the real brotherhood Shortly before the concert in Amsterdam, Michel Samson met with Ornette Coleman in Paris. “I was interested in contemporary music, hence also in contemporary jazz, and I knew that Ornette Coleman was interested in the violin. Therefore we were interested in each other. He invited me to join him in Amsterdam. After that concert I went back to America; I wasn’t at all looking for a career in jazz or anything like it. In April 1966 I was in Cleveland for a concert with the Cleveland Orchestra and Albert Ayler was playing in a club at the time. I called him and went to a rehearsal and I’ve been playing with him ever since. We don’t work regularly and my concert career can continue as planned. During the upcoming winter season I have engagements in America again and I’ve also become a professor, violinist in residence they call it, at the Farleigh Dickinson University in New Jersey.” Combining classical music and avant-garde jazz is rather unusual. Doesn’t his double career cause problems with his ‘classical’ connections? “No, I can explain to them that my profession is entertainer. It is true that only very few classical musicians have any feeling for the new jazz. Only Leonard Bernstein sometimes comes to listen to Ornette or Albert. The third stream doesn’t mean much to me. A large orchestra that is just put there to let some jazz guys play with it, that is not the real brotherhood. In daily life, classical musicians don’t even speak the same language as jazz musicians. In fact, I don’t like modern western music any longer. The way Karlheinz Stockhausen occupies himself with electronic music, there is no time for that anymore. In concerts, I prefer to play standard works; Beethoven, Brahms, Bach, Mozart. I don’t really try to play jazz. I do, however, imagine how a jazz violin should sound: but I don’t feel like a pioneer... like, how am I going to integrate the violin in the negro music or something like that. My contribution to the whole is what’s important.” Peace interpreted poetically Albert Ayler often uses the word ‘peace’, but Michel Samson emphasizes that their music has nothing to do with political protest. “Peace – you should take it poetically, not politically. It shouldn’t be seen as some kind of a beatnik tag, with a badge or something. It’s bigger, goes further than that. You can look at Albert’s music as some kind of church music. The titles of his compositions are quite religious, I’d say. Our music is a religion, of course, the majesty of the arts. Albert also sees it like that. He never plays with addicts for instance, people who cannot give their energy to the music, but have to give it to some other pseudo-important thing. We prefer to play in a concert hall rather than in a club; the atmosphere is purer there anyway. In America, there are only few musicians who view their music as pure. I really only know two, Albert and Trane; the others mostly play in clubs, in Las Vegas. For instance, at the moment they are trying to promote John Handy. Even though he plays free, you still hear some commercial background. It’s like doing what’s fashionable, it isn’t beautiful, not really felt.” Inspiration not very important The reproach that the new jazz is lacking in form doesn’t affect him much. “It is a free form. Coleman employs a rhythmic form, Trane a melodic form and this [i.e. Ayler’s] is a form in the shape of freedom, to play a solo in which everybody is listening to each other. In fact, chords come down to the same thing. Chords are taken too literally by bebop people. If you would interpret chords poetically... Take Mozart for instance, in classical music there also are forms, but the greatest composers always reigned majestically in interpreting those forms as freely as possible. If you would take our form literally, it would become a very complicated form. All these compositions would become more or less the same and it is possible to catch it in exact terms. In that sense it is connected with the classical form of chords in a chorus. Planned chaos? That sounds very distant from peace to me. Chaos as peaceful as the one created by us can only exist when there is real peace, that you take a solo and people silently stand by listening. It happens intuitively because it’s a unit. It’s about listening rather than thinking of chords. We listen to each other rather than thinking of where to put our hands. It is like a conversation, sometimes there are days that you don’t talk much. If I don’t feel like it, I just don’t solo. It’s not about inspiration, but about entirely different things. If for instance your hands are cold, your inspiration may perhaps suffer from the material battle, but generally speaking I don’t consider inspiration to be very important. One of the things that strikes me about Albert is that he never struggles with technique. Albert has a fabulous technique, nobody but he can make such long strophes on a saxophone .” Everybody in New York plays free The fact that today many musicians are involved in avant-garde jazz isn’t considered to be positive by Michel Samson. “With everybody making records for ESP, people like Ornette and Trane and Albert have become less unusual, while in fact they are still equally exceptional. All those people who have recorded for ESP aren’t as great as Ornette. You know, everybody in New York is now playing free. It’s fashionable like LSD. In Europe there only are copycats. When Piet Kuiters imitates Cecil Taylor everybody likes it, but in America that’s impossible! Piet Kuiters came to New York with Tchicai; nobody came to listen, only the Danish consulate. When I’m in New York, I only listen to Ornette and Trane and to Pharoah Sanders and Don Cherry”. [Originally published in Jazzwereld No. 11, March 1967.

*

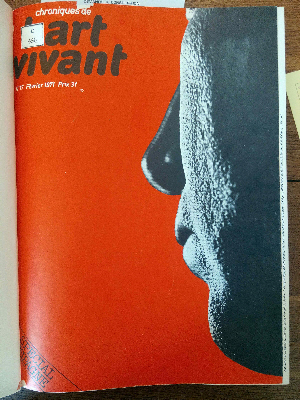

The Wire (No. 227, January 2003, pp. 38-41). Originally published in Chroniques de l’art vivant (No. 17, February 1971, pp. 24-25). |

|

|

|

|

The road to freedom This interview with Albert Ayler was conducted by Daniel Caux on 28 July in Saint Paul de Vence in the south of France, the day after the second of Ayler's two Nuits De La Fondation Maeght concerts, and four months before his body was found in New York's East River. On the tape, Ayler's voice has a strange, compelling quality, as he discusses his childhood and early career in tones that float between innocence, bewilderment and excitement. This is the first time the interview has appeared in English.Transcription and edit: Edwin Pouncey. Photos: Philippe Gras/Eye Control. |

|

|

First of all could you tell us when and where you were born, and speak about your family, your parents? |

|

|

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

|

*

BERNARD STOLLMAN - THE MAN FROM 5D

Strange things happen whenever I visit Bernard Stollman. He lives in an enormous sprawling apartment complex near the East River. I always get lost and inevitably wind up calling him from a pay phone (if I can find one that works), as I might be the last person in Manhattan not to own a cell. Even the panhandler on the corner who looks like the inspiration for the cover of Jethro Tull’s Aqualung has one. The last time I went to interview him I was writing an article for Signal to Noise on Albert Ayler (who Stollman is credited with “discovering”). And of course I got lost. The only thing I can seem to remember about his place is his apartment number – 5D. Bernard without a doubt is the man from the Fifth Dimension. And I’m not talking about that perky 60’s group who wanted to whisk you away in their “beautiful balloon,” although Stollman, as Sun Ra enlightened us sad earthlings, knows very well that “Space Is the Place.” There is something at once pragmatic and alien about Bernard. He always wears the same clothes - white shirts, gray pants and black suspenders. He lives minimally with just the essentials - a desk, phone, fax, computer, couch, a couple of African fetishes hanging on the wall and a pile of CD’s - mostly ESP stock and a handful of books (his favorite being Alice In Wonderland). Stollman is tall and bald with intense blue eyes. This time I’ve come to interview Bernard about his recently resurrected label, ESP Records. His catalog of free jazz and sixties radical folk rock is now back from oblivion. As I said, weird things happen whenever I visit him. The last time I interviewed Stollman I got home and discovered there was nothing on the tape but undecipherable gobbledygook – Pakistani pig Latin from cab-drivers lost on Avenue D. It was then I recalled an old episode of Seinfeld in which Elaine has a psychiatrist boyfriend who wields a strange control over her. She tells Jerry she thinks he is a “Sven-jolly.” Jerry corrects her, saying it’s pronounced “Svengali.” But it turns out that Elaine was right. There is indeed such a thing as a “Sven-jolly!” And Stollman is living proof. Since I was a teenager, buying his weird records, this mystical prankster has had a hand in shaping (or should I say warping) my consciousness. As Bernard is a lawyer I’ve considered suing him. First of all, I risked life and limb sneaking the Fugs’ records into our house. If my dad ever caught an earful of Sanders’ twisted anarchist lyrics he would’ve opened up Sam’s Club size can of whup-ass on me that I’d never forget. In fact, if I hadn’t become obsessed with ESP I perhaps might have grown up to become the accountant my dad had hoped for and gone into the family business and would’ve had my taxes done by now (April 12th) instead wasting my life playing mandolin and banjo with Peter Stampfel (of Holy Modal Rounder fame and an ESP alumnus) and writing articles for esoteric magazines like Signal To Noise.

The story of ESP began in 1964 in the basement of an Israeli coffeehouse called the Cellar Cafe at 90th Street and West End Avenue during a three night music festival called ‘The October Revolution.’ Although it was rumored that Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor had a hand in producing the event, neither were to be found. “It was a who’s who of improvisational music, that included Sun Ra and Marion Brown and Burton Greene,” Stollman recalled. At the time Bernard lived in the neighborhood and stopped down each night to the jam-packed café to hang out and dig the music. “I think they held it at the Cellar because the word was out that Stollman was interested and they wanted to lure me in,” Bernard chuckled, recalling Paul Bley playing an out of tune upright piano while Giuseppe Logan blew clarinet, standing in the doorway while Archie Shepp, (who was under contract to Impulse Records at the time) floated about, checking it all out. “There was no amplification of any kind. No heat or lights,” Bernard recollected. “I had gathered they burned candles because the electricity had been turned off.” After his transcendent performance, the intergalactic bandleader Sun Ra invited Stollman over to his loft in Newark. Entranced by his otherworldly sounds Bernard obliged and asked Sun Ra to record for ESP. Stollman was so taken with bassist Ronnie Boykins’ playing that he spoke to him in private and offered to record him for ESP as well. “He said ‘I’ll let you know,’” Bernard recalled. “Eight years later he called, and said ‘Bernard, I’m ready to record!” Stollman said with a chuckle. “Then Ronnie assembled his group of superb musicians and did a fairly laid back album at Marzette Watts’ studio.” “They say fools rush in where angels fear to tread,” Bernard said rolling his eyes. “I was just a naïve individual who saw that something must be done. These people needed to be recorded or their work would be lost. They were in their prime. While Impulse Records recorded John Coltrane they were totally loath to go near the new generation. There was a big gap. Nobody would touch them and yet they were ripe, mature and ready to go,” Stollman explained. “I walked in on it and did forty five albums in eighteen months.” Stollman recorded Pharaoh Sanders’ Pharaoh’s First for ESP in September 1964, describing the tenor saxophonist as “hostile, suspicious and surly. He chatted with the engineer about how he wanted to the mikes set up. They did the session. I paid them and they left and I didn’t see them again for thirty five years!”

Bernard was not a hands-on producer. His role was simply to provide the tools, the studio or whatever the musician needed to create and then get out of the way. “I didn’t want to be ‘the man,’” Stollman said with a laugh. “While I did attend some sessions, I often did not deliberately, because my presence could very well alter it somehow. I might intimidate someone. I wanted to be as unobtrusive as possible. So I didn’t attended sessions and I missed some extraordinary moments. It was just my sense that being there might not have been helpful.” Without any kind of creative supervision the musicians were ultimately on the spot to deliver. And whatever they played was then released by ESP. “I wasn’t going to second-guess the artist’s work. He’s the expert on his own music!” Bernard emphasized. “They could never say later on that they had some great ideas but that son-of-a-bitch producer got in my way. So the opportunity was there for them to wail. And that is just what they did!” “I didn’t realize it for many years but the label, ESP, was my art,” Stollman said. “The word ‘producer’ has always given me trouble. The artist produced everything! I am a coordinator.”

“Eventually ESP drew the interest of the Fugs, who were iconoclasts, the darlings of a new literary age,” Bernard said, recalling the first time he went to the Bridge Theater on Saint Mark’s Place to see Ed Sanders, Tuli Kupferberg and company. “You couldn’t hear them. It was just a roar of noise. The equipment was so dreadful. You couldn’t hear a word! They weren’t really making music really. It was poetry.” A few days later Bernard had lunch with Ed at the Paradox, a macro-biotic restaurant and suggested they create a pop music subsidiary of ESP but Sanders, Stollman was surprised to discover, deliberately wanted to be associated with Albert Ayler, Ornette Coleman and Sun Ra. “No one connected the free jazz players with the radical movement,” Stollman said. “It needed language before anyone woke up to what was going on. The sound of that music was absolutely the most radical sound of its time. But it went right over most people’s heads. Tuli Kupferberg’s ‘Kill for Peace,’ and Tom Rapp’s ‘Uncle John,’ had incredible lyrics.”

The Fugs had vehemently opposed the Viet Nam war as did Pearls Before Swine while the anarchist antics of the Holy Modal Rounders were the auditory equivalent of the Marx Brothers with a head full of acid. Ayler’s spiritual wail, Pharaoh’s apocalyptic skronk and Sun Ra’s universal sound of love created the perfect soundtrack for reading radical sixties manifestos such as Eldridge Clever’s Soul On Ice, Che Guevara’s Guerilla Warfare and Abbie Hoffman’s Steal This Book.

ESP’s philosophy was the antithesis of the record industry at the time - “The Artist Alone Decides What You Will Hear,” was their motto. Trusting their instincts and sense of aesthetics, Stollman handed over total control to his musicians. They chose the graphics for the album cover as well as the music within. And it all worked quite well for a while. With three records on the pop charts in 1968, two by the Fugs and One Nation Underground by Pearls Before Swine, ESP artists were not only outspoken and outrageous, they actually sold thousands of records! Bernard’s little cultural revolution not only raised the ire of the record industry, it would soon catch the attention of United States government. “My phones were tapped. One day I got a call from a lawyer. It was an innocuous conversation until he suddenly quoted a phrase from something I had said the day before. There was no way it could’ve been a coincidence,” Bernard imparted. “So he must’ve been among the crowd monitoring my conversation.”

Warner Brothers soon called looking to buy out the entire ESP catalog. Stollman suspected their true motive was not to further the music but to suppress the Fugs and the Pearls. “I didn’t have either band under contract except for those specific albums. If I record an artist I will not sign them to a long-term agreement. It’s antithetical to tie up an artist and suppress their creativity. They were totally free to go to Warner Brothers if they wanted. And they did! But they soon fell into a trap. From that day forward neither one expounded against the war. In terms of personal actions they continued to protest (Sanders and a slew of Yippies actually tried to levitate the Pentagon in 1968?) but as far as Warner Brothers were concerned, they kept a tight reign on them as artists. Country Joe McDonald and Phil Ochs were among the few musicians who were blatantly anti war at the time that enjoyed major label support.”

“Once I said no to Warner Brothers our record sales stopped cold overnight. The pressing plant began bootlegging the records. They pressed them and sold them to our distributors! There were no laws against it at the time! I was very dense and didn’t grasp what was going on,” Stollman explained. “I went down to the plant and looked for my album jackets. I had given them several thousand as a back up but there were none there! That was the end of that relationship. I got a trucker and went through this vast warehouse and collected all the stuff that wasn’t selling, mostly jazz records and albums by the Godz. Effectively I was out of business. The core of my business had been the pop records and that was gone.” By the end of 1968 Bernard let his staff go, gave up his office and began to operate out of his apartment. “I was profoundly dumb,” he confessed. “It was so obvious it was over but I just didn’t want to know.” For six years Stollman continued to tread water, accomplishing little while exhausting whatever money he got from his family. In 1974 with no hope left he closed ESP, and paid off his creditors (“who,” Bernard claimed “were the very same people who’d been stealing from me.”) “I was so mortified by the history of my label, I had seen it as such a failure that I hid from everyone. Nobody saw me. I didn’t go to record stores or concerts. The word was I had died. Actually I’d gone straight,” Stollman said, referring to a dreadful bureaucratic job he’d taken as an assistant attorney general representing psychiatric centers. “I just went to work every day for ten years at Number 2 World Trade Center on the 46th floor. Then in July 1991 two things happened. I turned 62 and was forced into retirement. I had a tiny pension and moved to a farm in the Catskills. In December of that year, I was in the depths of depression, going nowhere, when a German label called ZYX contacted me. They knew from nothing. They were a dance company who listened to a consultant friend of mine who knew our catalog back and forth. The records had never been out on CD before, so they put out every record I ever issued – 115 titles, with a 42 page color catalog which must have cost them a pretty penny. Suddenly we were back in business.” ZYX bought rights to Bernard’s catalog for six years, selling old ESP records on CD all over the world. The only trouble was they stopped paying royalties. “We’d get statements for five copies of this or that,” Stollman admitted. “Then we put out fifteen titles with a Dutch company called Caliber who went broke. They sub-licensed the records to an Italian company called Abraxas for three years. But for the last two years we haven’t received any statements or royalties from them. Artists say to me, ‘Everywhere I go I see my records. Where’s my money?’ But they don’t understand that people haven’t paid us the royalties. And there’s also bootlegging going on but it’s a compliment of sorts. Last spring our contract with Abraxas expired but they kept right on pressing the discs. How do we stop them? Now we have to go to federal court with their American distributors who have been part and parcel to it. They released records by Albert Ayler and Tom Rapp but haven’t paid us a dime. The only thing we can do now is to re-issue our catalog as fast as we can.” Stollman and his small staff of three currently operate out of his one bedroom East Side apartment. The digitally re- mastered discs they are in the midst of compiling are far superior, sonically speaking, then what’s out there. Combining old albums by Albert Ayler (Bells and Prophecy) Pearls Before Swine (One Nation Underground and Balaklava) and Sun Ra (Heliocentric Worlds Vol. 1 & 2) as twofers, the new releases also feature additional material including extra tracks and interviews. There are also new unreleased tapes from the vaults by Albert Ayler – Live on the Riviera as well as Sun Ra’s Heliocentric Worlds Volume 3.

The new ESP catalog will also include unreleased live sets by Chet Baker, Art Blakey, Charlie Parker and Billie Holliday as well as a box set of live performances by Miles “We’re working with Greg Davis, Miles’ oldest son, as well Evelyn Blakey on these projects,” Stollman pointed out. In an age stifled by Neo-cons controlling Congress as well as the jazz series at Lincoln Center, the return of ESP is a welcome antidote to a painfully sober era. With luck (and more than a little money) perhaps Mr. Stollman can help ignite America’s consciousness once more and pave the way for another generation of great explorers of the outer fringe. JOHN KRUTH *

[This interview with Michel Samson originally appeared in a Dutch magazine (.pdf available here). The following translation was kindly provided by Kees Hazevoet.]

Adventures in the New Thing By Rudie Kagie In 1965 he played with Ornette Coleman and from April 1966 with Albert Ayler for a year and a half. But the Dutch violinist became interested in other things and said goodbye to Ayler and his music. To capture his memories, Rudie Kagie visited him in his present hometown of Louisville, Kentucky. ‘The violin’, says Michel Samson (1945). ‘Everything I know about politics, history, art – about everything, I know because of the violin. From age five onwards that instrument has completely dominated my life.’ On American record sleeves of Impulse and ESP his surname is consistently spelled wrong. Sampson really has to be without p (although correction would by now only create confusion, because the error has been repeated on almost all cd reissues). The invitation from Samson to come and look him up in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky, dates back from a previous meeting in Amsterdam twelve years ago. It took a while to materialize. Diehard fans of the New Thing of the 1960s will perhaps remember Michel Samson as the white, clean cut, always dressed in black suit, Dutch young man who – outwardly unmoved – accompanied the free tenor improvisations of Albert Ayler (1936-1970) on violin. As a pioneer, Samson deserves more than just the footnote in the history of the avant-garde that he has been allotted – just take the reproach in [Dutch newspaper] Het Vrije Volk, which, after the concert in the Doelen, Rotterdam, accused him of ‘lust-murdering the violin’ – even though he considers the year-and-a-half during which he handled the bow at Albert Ayler’s side as a musical aside. He has done more important things in his life, he says. He talks passionately about his painting, in which he now invests a lot of time. In the car, during the drive from the airport to his home on the Fairhill Drive in Louisville, it already becomes clear that past fame barely occupies him. Gee, is Donald Ayler, the mentally unstable younger brother who played trumpet in Albert Ayler’s band, already dead for five years? The obituary had escaped Samson’s notice. What he does remember: ‘Let’s practice soundwise’, the strange Donald used to say. Nerves of steel It took half a life before Michel Samson understood why his father insisted that his son had to become a concert violinist. The violin was the instrument that would change everything for the better. His father – painter and draftsman of portraits for court records in [Dutch newspaper] De Telegraaf – was Jewish, his mother catholic. ‘That I had to take violin lessons was a post-war revanche, an attempt by my father to salvage the honour of family members that had been deported’, reconstructs Michel Samson. ‘No instrument more Jewish than the violin. Almost literally a weapon. Comparable with bow and arrow. When you hold a violin for the first time, you feel the great tension of the strings. To play the violin well, you got to have nerves of steel. An uncontrolled movement can be heard around widely. The violin is a time bomb.’ Ever since his childhood, Samson says, he has been driven by ‘a great appetite for all kinds of music’. He didn’t want anything but to please his father, his father who thought practising to be more important than regular teaching. He withdrew his three children from school in order to teach them himself – until the school inspector rang the bell and return to the classroom was inevitable. Love for jazz was fed by jazz records from the collection of the American embassy. Besides, young Michel Samson had noted that, during the 1950s, the winners of important classical competitions for violin and piano always originated from either America or Russia. If he really wanted to accomplish something in music, he had to travel the world, away from The Hague. Perplexed In those years, musical masters of world fame weren’t as unapproachable as today. In 1961, Michel Samson (who was 16 at the time) called up his big example, Yehudi Menuhin, at the Amstel Hotel in Amsterdam. ‘Come along tomorrow morning when I’m rehearsing Brahms with the Concertgebouw Orchestra’, the maestro told him. The invitation resulted in an unforgettable experience. Samson: ‘I waited for Menuhin at the artists’ entrance of the Concertgebouw, went upstairs with him and had to wait until the rehearsal was over. When he came back, he made me play Bach’s Chaconne in front of the people who were with him. After that he made everybody leave the room and told me what I was doing wrong in his view. That was on a Wednesday. The next Saturday he was going to perform at the Kurhaus in Scheveningen [near The Hague]. If I’d pass by before the concert, we could talk some more and I could demonstrate the progress I had made. While we were sitting together in a room, all of a sudden the door flew open. Menuhin’s impresario looked at me furiously and yelled: “Out you! This man here is like a child, he doesn’t realize that he has to play Brahms in a few moments!”. The great Menuhin was perplexed, with a face asking ‘what’s going on here?’. Sometimes there was a strange inconsistency in his playing. If he hadn’t prepared himself well enough, he had difficulty handling his bow. Shortly after, Michel Samson went to Baden-Baden with the Lorelei Expresse to take part in a summer course for young violinists, where he received tutorage from his Polish-Mexican role model Henryk Szeryng. One year later he obtained a Dutch scholarship and went to Rome to study at the Academia di Musica da Camera to study with the Argentinian violinist Alberto Lysy and, through him, with many other great names. ‘In Rome I met with the Living Theatre, who were performing their play Mysteries and Smaller Pieces. Towards the end, Piet Kuiters strolled on stage with a saxophone and improvised until the audience left when they understood the play was over. Kuiters wasn’t really a saxophonist, but a pianist. I loved that free jazz. If you enjoyed hanging around there, you automatically became a member of the Living Theatre. What Piet Kuiters had been doing on saxophone, I was doing with the violin – I filled up the part at the end of the performance. ‘In Trieste an interesting incident happened during an episode called The Plague. The actors spread through the hall and acted as if dropping dead. They were carried away on stretchers and piled on top of each other. That growing pile of people offered such a horrifying sight that someone called the police: this couldn’t be, this shouldn’t be. The police indeed arrived, but when the actors were summoned to get on their feet, they just kept lying. The officers started to beat and club them. Typically 1960s’. A boy’s dream While being away from Rome for a short holiday, Samson seized the opportunity to attend the first concert by Ornette Coleman in the Netherlands during the nightly hours of October 29, 1965 at the Amsterdam Concertgebouw. Just like he previously had approached Menuhin, he now contacted Coleman. And successfully so, witness the (anonymous) review in the [Dutch newspaper] Algemeen Handelsblad: ‘The atmosphere of the finale was one of a happening. Ornette Coleman grabbed his violin, another violinist joined the trio, together with bassist Izenzon they executed a serious remodelling as well as a fascinating background for Dutch trumpeter Nedly Elstak, who joined the group at Coleman’s request’. A boy’s dream came true, Samson says while looking back at this historical concert. In a phone call to impresario Lou van Rees’ office that afternoon, he learned that Coleman was staying at the Krasnapolsky Hotel. He admired the musician that improvised on a plastic saxophone, but was even more intrigued by rumours that the great Coleman had also taken up the violin. ‘I thought it would be fantastic to play free jazz with him on the violin. During the late afternoon I went to the Krasnapolsky Hotel. At the bar I wrote a note for him, explaining that I was a violinist and would like to meet him. Ornette was sitting in the restaurant, read the note that the waiter gave him and waved to me to come over. Later, in his room, he asked “Would you like to play something?”. I played some Bach, solo, which he liked a lot. Then he asked me the most important question someone ever asked me: “Can you play something that is in your head?”. I had never thought about that before. ‘He invited me to come to the concert that night. There would be an entrance ticket for me at the counter. I had a balcony seat. After the first set Coleman took the microphone and asked : “Michel are you there? Why don’t you come down, man, and play with us?”. While the audience applauded I came down the stairs of the Concertgebouw to play with him. An amazing experience. Of course Coleman wasn’t a great violinist. He just scratched away, but I thought it was great that he did it. Much later I found out that it had already been done long before. The way the composer Count Gesualdo da Venosa applied Greek musical theory to his madrigals was more way out than Ornette Coleman – and that was during the Renaissance!’. Warm and sweet ‘I wanted to go to America, because that’s where it was happening. At the time, the most important training institute was the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. All violinists winning at international competitions were from Curtis, not from Juilliard. If you were admitted to Curtis, training, food and shelter was paid for. Late in 1965, I went to New York by ship of the Holland-America Line. I paid for the trip by playing four times aboard the Nieuw Amsterdam. Twice first class and twice second class. ‘I arrived in New York, December 18. Right away, I could stay with the theatre critic Michael Smith of the Village Voice. The Living Theatre had given me a list of people I could contact once I was in New York. It was like one large family. At the time, everybody was very warm and sweet. The fact that I looked good may have helped, as many of these contacts were gay’. (Michael Smith published parts of his diary, full of sex and drugs, from the hectic 1960s on the internet. On December 19, 1965 he noted: “Two young Dutchmen, Oliver Boelen and Michel Samson, friends of Rufus’s, were in the living room when I woke up. [....] I invited them all to come to Judson for the matinee. [....] Joyce held up her cup to ask if a wanted more wine. I said not. She is talking to Gordon. The Dutch boys want to stay at Joe’s but he doesn’t want them to. Gordon drove Joe, Lee and me to the Village in his Porsche. He went home and they came up. Charles took Oliver and Michel to his house to sleep.”) Michel Samson continues: ‘Max Tak – a violin freak, who could fix things for Dutch artists – worked at the Dutch consulate in New York. Through him I could audition with Ivan Galamain, a big name who had produced well-nigh all big stars of the second half of the 20th century. Galamain also taught at Curtis and arranged for me to be admitted there. Meanwhile and thanks to Max Tak, I regularly had gigs. ‘The writer, Peter Bergman, who I had met through the Living Theatre in New York, called me at the Windermere at 92nd Street where I was living. His father was about to open a men’s fashion shop in Cleveland, Ohio. Peter thought it to be a good idea for me to play some at the opening. I could use the money and at the same time I could choose a new wardrobe at that shop. ‘That’s why I was in Cleveland on Saturday April 16, 1966 where, as I had read in the newspaper, Albert Ayler’s quartet would perform at the La Cave jazz club. During the afternoon I went there and found Albert rehearsing with local musicians and, of course, his brother Donald on trumpet. I introduced myself and said that I had played with Ornette Coleman in Amsterdam. “Do you have your violin with you?”, Albert asked. From that moment on we hit it right away. That night I played in his band and the following night again, at the same club. Obviously, I was wearing my new suit that I had been allowed to choose at the fashion shop the other day’. ‘After the concert Albert said: “We’ll play at Slugs in New York on May 1st, will you be there with us?”. Of course I was! I haven’t kept a count, but I think we performed together some 30 to 50 times in total’. (In the liner notes of the Impulse album Albert Ayler in Greenwich Village, Nat Hentoff quoted Albert Ayler: “From the beginning, we hit it off musically. Michel, too, is a man who spent a long time searching for peace’.) An endless number of joints An exciting time, you may perhaps think. But according to Samson it wasn’t that exciting at all. Of the legendary jazz club Slugs, he mainly remembers the ‘pretzels and peanut shells on the floor’. For the rest, time mainly passed with smoking an endless number of joints. Before morning rehearsals at the aunt’s home in Harlem (where Albert and Don usually spent the night dozing in a chair), Samson was picked up at the nearby subway station, as it was too dangerous for him to walk in the neighbourhood with a violin case all alone. The rest of the day they strolled the streets of Manhattan, ‘hoping that a crumb would fall their way’. ‘We brainstormed endlessly about commercial success. Albert didn’t intend to cause confusion. He wanted to make it and be part of the establishment. This came with a certain degree of opportunism. I think that me being part of the band was because having a white violinist from Europe made it easier to gain a foothold with record companies and jazz clubs. Becoming famous was part of the 1960’s. The Beatles and The Rolling Stones were the great examples. ‘Albert wanted to tour in Japan and was considering to incorporate Japan-like themes that the Japanese would like. At the time, Art Blakey and all those boppers were beginning to make real money in Japan, not in Europe. Albert relentlessly tried to get access to the mighty producer and impresario John Hammond, the man who could arrange a contract with CBS. At long last we got an interview, but Hammond thought nothing of what Albert was doing. Instead, Hammond gave me a contract. ‘I think it had to do with him being the brother-in-law of Benny Goodman, who had been a good friend of Béla Bartók and the famous Hungarian violinist Joseph Szigeti, a Bach specialist. Somehow it clicked between us. John Hammond has helped me a lot getting studio gigs. As long as it earned me money, I didn’t mind. ‘Through Hammond I came in touch with John Handy, an alto saxophonist who was selling quite well at that time. Miles Davis came over to listen when we played at The Dome. After the concert, Miles came to me and almost wanted to punch me in the mouth. He thought I was disloyal to Albert. “Why are you playing that boogaloo fuckin’ music man?”. Miles thought John Handy was a complete zero. The opportunist side ‘A removal began to arise between Albert and me. I shouldn’t be allowed to play with John Handy. He was jealous. As for myself, I got increasingly fed up with the pseudo-religious and would-be philosophical bullshit that Albert came up with. The rhythm section was constantly changing. The dialogue would go: “Well, man, Sunny [Murray].... he doesn’t have that energy, man...”. One month later it was: “Well, Beaver [Harris], he is a funny cat, but he doesn’t have that energy”. The musical judgment had nothing to do with knowledge or rationality. Or it was expected that the sidemen would take a very humble stance. ‘I didn’t suffer from that. I didn’t need to be humble, I could as well have come from another planet. It was just approaching the end, at all fronts. Albert Ayler’s music woke up something in me that didn’t need to be woken up anymore. I thought it was leading nowhere’. That Samson always felt like an outsider in Ayler’s bands, also shows between the lines in the only interview with Samson from that time which has been preserved. (Even the very detailed archive of newspaper clippings of the Public Library in New York doesn’t have any references). After a concert with Ayler at the Berliner Jazztage 1966, Bert Vuijsje interviewed the violinist for an hour for [Dutch magazine] Jazzwereld (No. 11, March 1967). Significantly, the headline read: “I don’t really try to play jazz”. The interviewee spoke passionately about the great classical composers, but he hardly mentioned jazz at all. It was clear how he felt about the direction his future should take. Michel Samson now: ‘The last time I played with Albert was at the Newport Jazz Festival 1967. When, in 1968, that R&B album New Grass came out, I already couldn’t care less. After John Handy, I quitted jazz completely. This also had to do with a growing aversion against the opportunistic side of myself. I had other interests. I wanted to paint, perhaps a career as conductor’. ‘I indeed began doing these things. I was assistant-conductor with several American orchestras and also conducted Dutch orchestras. I never became an American citizen. From 1981 to 1985, I lived in the Netherlands, where I was deputy leader of the violas with the Omroeporkest (Radio Orchestra). However, the woman with whom I was married at the time and the children couldn’t settle in the Netherlands and we went back to the USA. For 15 years, I taught at the University of Louisville. In 1997, I became a violin dealer, that is to say: European representative and partner of Bein & Fushi in Chicago. I always did the visual arts as a side line. Every now and then the past knocks at his door: is he perhaps the Michel Sampson who played violin with Albert Ayler in the 1960s? Sometimes he gives an interview for a documentary or a book about that period. Many times he has been asked to revive the musical revolution of Albert Ayler on stage at a festival or in a recording studio. ‘I never responded to those requests’, he says. ‘It is gone. It is meaningless to try and repeat something that is so much connected with a certain time period’. [Originally published in Jazz Bulletin No. 83, June 2012 *

|

||

|

Home Biography Discography The Music Archives Links What’s New Site Search

|

||