|

Spiritual Unity

Down Beat (Vol. 32 No. 15, July 15, 1965 - p. 29-31) - US

TWO VIEWS OF THREE OUTER VIEWS

Albert Ayler

SPIRITUAL UNITY—ESP Disk 1002: Ghosts: First Variation; The Wizard; Spirits; Ghosts: Second Variation.

Personnel: Ayler, tenor saxophone; Gary Peacock, bass; Sonny Murray, drums.

Rating: no stars

Byron Allen

BYRON ALLEN TRIO—ESP Disk 1005: Time Is Past; Three Steps in the Right Direction; Decision for the Cole- Man; Today’s Blues Tomorrow.

Personnel: Allen, alto saxophone; Maceo Gilchrist, bass; Ted Robinson, drums.

Rating: *

Giuseppi Logan

THE GIUSEPPI LOGAN QUARTET—ESP Disk 1007: Tabla Suite; Dance of Satan; Dialogue; Taneous; Bleecker Partita.

Personnel: Logan, tenor and alto saxophones, Pakistani oboe; Don Pullen, piano; Eddie Gomez, bass; Milford Graves, drums.

Rating: no stars

It’s clear to me that Ayler is from the avant-garde institution. But there is good and bad avant-garde.

From the beginning, Ghosts: First Variations is satirical comedy. In order to make this more successful, it seems he would apply the “fog horn” sound in a fuller context, at least making it parallel with itself. This track sounds as if it is an attempt at putting the listener on.

After the first chorus, Ayler does something—I don't know quite what he is trying to do—but it sounds kind of like a baby crying for candy with a whining ball in its mouth—wanting to play music and not wanting to, while holding a musical instrument.

After a bewildering solo by Peacock—who I didn’t know had such want-to-get-away-from-it-all, high-minded, uninhibited aspirations—Ayler returns, this time turning the clock back (counterclockwise)—all the way back—to folk- country, Ozark, real 1920s Texas hillbilly musical gyrations. Then they go back to the melody and fade out. If the townspeople hear this, I’m sure that when the second variation of Ghosts is played, there will certainly be a ghost town. No one left but. . . .

The Wizard is angry tonight, and from all indications he has the rest of the group boxed in. He and Gary. I wonder what the drummer would do with some precisioned sound, like a melodic instrument in hand. I like Murray best of all, but I also like Peacock for being a diehard.

There are a lot of unexplored territories in music (at the moment, that is) without going into areas that leave us earth people so far behind, or far away, or without leaving us so far “in.” It must be awful to study for years to get away from the gravitational pull of inhibitedness to find there is nothing at the heights to which thou hast extended thyself.

Ayler seems to have a nice full tone on Spirits, but it’s hard to tell. Is he playing with a mouthpiece? I heard Roland Kirk play without a reed and get sounds like this, but he had a conception of melody and chords. I don’t have the spirit to listen to more of this one.

I’ve heard Peacock play “conventional,” so I know he can play more to my liking and that he knows chords, cycles, etc. A gig is a gig? If this thing isn’t quarantined, we’ll all be in the garment center pushing wagons.

Ghosts: Second Variation is about the same as Variation No. 1. Ayler is really stretching out here, and I’m convinced he doesn’t know or care anything about conventional music.

A baby can do this if it can produce the air for the sound. A baby is free. Ayler is free. Free as a bird. Ayler is free of everything except melody and Father Time (the march of time itself—clock and cadence). He sounds like a very frustrated person. He is also playing a very controversial music. At this point it’s not worth the paper it takes to review it. Too far out. He passed the moon and the stars.

The Allen record is a little better.

The bass does string and bow calisthenics on Time, so I don’t suppose he was tuning up. Allen enters, playing a horizontal line that has nothing to do with chords or anything being played by the others except an occasional cadence. If these guys are going to play in time, then they should play some chords. This would at least form a design, but this is drama beyond conventional description.

Bass calisthenics and then drum calisthenics. But at least the drummer plays some good rolls. Then the alto comes back, and they’re really trying to get something going. Whew! This track is trying.

On Three Steps, Allen comes closer to playing something than Ayler does. Allen’s tone is kind of “mousy,” but he doesn’t squeak. Robinson sounds all right on drums.

Gilchrist stretches out on Steps, but he doesn’t seem to know where he’s going—or does he? I can’t hear where he’s making any steps in a musical direction. I wonder if he ever heard of Ray Brown or Oscar Pettiford? Or even the more recent “spare bass” style exemplified by Scott LaFaro, Richard Davis, Charlie Mingus, Steve Swallow, and Ronnie Boykins, to name a few. After these spare bass players put you on, they play extraordinary combinations of “in” and “out” stuff; however, their put-on (I may be exaggerating a bit) is mathematical (precisioned) because it’s right in some chord (it sounds such).

Cole-Man begins with a bombardment of synchronized rhythm section and horn ensemble before the three men battle it out. I like to hear some point of rest, unless the idea is to leave one hanging in suspense near the cliff’s edge. Allen almost gets going here, but this music is ugly. There is enough of that in the world, even for those who seek perfection.

Robinson really pushes to make Blues go, but the bassist pushes a lot of strange buttons. Allen, however, plays some nice folk hollers. This is the best track, but the album as a whole passed this earth person and most of the stars.

The Logan album is the worst of the lot.

Taneous begins with a free-for-all conglomeration of noise, sounds, and tempos, with the drummer playing a synchronized cadence. I suppose this is an alto being blown into or blown around. A good grip on the instrument might have enhanced the aim. Piano follows the alto with a futile attempt to get some jazz going. Nothing happens. The bass follows with seemingly no idea of what to express; then the piano joins, in the same context. Finally Logan enters riding oboe, I think. The drummer does a few gymnastics, and they all join in for a free-for-all outgoing.

Pianist Pullen plays the introduction to Bleecker, laying a nice carpet for Logan’s rendezvous with Satan on the oboe. The oboist doesn’t like much that’s conventional, and when he does, he reminds me of Jackie McLean on a freedom excursion. In other words, Logan is not original when “in.” When “out,” it’s out for the sake of being out.

Contrasted with Logan’s oboe, Pullen’s piano solo is unusually pleasant, while drummer Graves keeps something going on, seemingly mostly for the sake of filling in. But when Pullen plays some block chords, Graves plays a nice roll on his hi-hat, which makes for a professional bow-out.

There is an ensemble goulash and then accompaniment for Logan, who bows out gracefully with all participating harmoniously. Quite a relief. The title is quite appropriate, assuming this is a party on Bleecker St. in New York’s Greenwich Village. An “out” orgy.

Tabla Suite and Dance of Satan begin with oboe (?) and bass up front, with Graves playing sticks across the bass’ strings. The pianist seems to be cleaning off his instrument’s strings at this point. Rhythm is being played on the body of the bass, while Graves plays on the strings, seemingly below the bass’ bridge. Logan enters on oboe (?); piano enters playing in 7/4 with Logan, but it doesn’t stick to a set rhythmic pattern—seems to overlap. Smoke-screen 7/4 (can’t exactly tell what it is).

A musical instrument didn’t necessarily have to be used for this music, because such an instrument is a precision instrument constructed for a definite purpose. As very little is definite here, a bamboo cane, water hose, or a rubber ball with a hole in it would have sufficed. Then one could place all this in a category of its own—not jazz, not miscellaneous jazz, but something like miscellaneous (musical) vibrations.

Dialogue is basically a four-part, go-for-yourself thing. The pianist is very agile and flexible, however.

For some unknown reason, I could take Logan under specific conditions. But he better get out of that smoke-filled room, walk out on Bleecker St., and catch some air.

(K.D.)

Kenny Dorham

Albert Ayler

SPIRITUAL UNITY—ESP Disk 1002: Ghosts: First Variation; The Wizard; Spirits; Ghosts: Second Variation.

Personnel: Ayler, tenor saxophone; Gary Peacock, bass; Sonny Murray, drums.

Rating: see below

Byron Allen

BYRON ALLEN TRIO—ESP Disk 1005: Time Is Past; Three Steps in the Right Direction; Decision for the Cole- Man; Today’s Blues Tomorrow.

Personnel: Allen, alto saxophone; Maceo Gilchrist, bass; Ted Robinson, drums.

Rating: see below

Giuseppi Logan

THE GIUSEPPI LOGAN QUARTET—ESP Disk 1007: Tabla Suite; Dance of Satan; Dialogue; Taneous; Bleecker Partita.

Personnel: Logan, tenor and alto saxophones, Pakistani oboe; Don Pullen, piano; Eddie Gomez, bass; Milford Graves, drums.

Rating: see below

These three records are best heard as a document from the center of contemporary jazz, not as finished, definitive performances. The music, however, is not merely experimental. It is fundamental to the lives of the many men making it. The ability to form rounded judgments of the music seems less appropriate than the ability to suspend that judgment willingly. The focus must be on the aperture of one’s ear. Criticism of the usual sort (especially ratings) would be a burden all around.

The records sat around my house for a long time before I would let them get to me. And yet my immersion in making similar music is what sustains my days. How could these records be so close, so valuable to me, yet seem so unlistenable, so unattainable?

Let us begin with what is clearest. There are moments in this music when something happens so strongly together that there is a flash of brilliance and a lingering radiation. The best musicians get it brightest, oftenest. But all groups get it sooner or later; it is a condition of playing this music.

It also is clear that there are painful passages of alienation, note-swept, dry. The music bubbles like black broth and is just as repellent, just as empty of music. How can these extremes be possible? What is happening to allow them?

The primary thing is this: many men are suddenly laboring very hard to find a new language that will express a new grace within the human condition. It is the labor that strikes us most. The lack of clarity of the language defines only the certainty of the toil.

When one senses that toil, one also senses those celebratory passages in which the work carries its own weight and the men ride it like hussars. But it is the toil, the necessity to toil, that comes first, and only after that can the music, sometimes, flow.

Now, are we to buy records just to listen to sweat? There is no answer except: here are the records at the listener’s disposal.

It is not remarkable that so many men want to labor together so fiercely. (There are dozens in New York, dozens elsewhere, many of whom sound much the same.) It would be remarkable if any of these records sold over 2,000 copies. Society does not want to share in this particular act of labor. The work is too unproductive, in the understood sense, too liable to error, too hard. Society will wait till the work straightens itself out and then maybe take a peek. Meanwhile, society will water the lawn, perhaps the best thing to be done. Certainly critics aren’t going to help matters by clearing away underbrush impeding the progress of short men.

The following remarks are written, then, as a musician, not as a critic. They are opinionated and intuitive; they spring from varied and contradictory tastes; and they have, I am confident, no corroborative rationale.

In the music of the Allen trio there is an evenness, not the usual intensity. The pieces generally begin and end well but often run into serious trouble along the way. No listener, however, could doubt that feelings pass between these men like circles pass through circles on water. One is present at the unfolding of the language.

The worst difficulties are textural. As in much of the new jazz, the textures are little more than textures (like the feel of a fabric, not its detailed construction). As such, they have only coloristic interest. When the textural phrases are shorter, the music becomes more interesting. Contemporary classical music learned this lesson the hard way, too, but a while back.

And formal problems: the solos seem out of place and too long sometimes—I mean especially the drum solo in Blues and the bass solo in Cole-man.

There are constantly recurring stylistic oddities. In the midst of so much melodic freedom, the rhythmic and metric rigidity is boring. This is similar to the texture problem.

Gilchrist is an inventive and dramatic bassist (lots of plot). He sustains without complexity—a rare talent.

Robinson is a good group player, but I don’t find his work outstanding.

Allen is more openly indebted to the mainstream from Charlie Parker than are most avant-garde players. There is the desire to go beyond, but no tangible rebellion against, the old school. His boppish licks sound good, in a way; they are an affirmation of the old in the midst of the search.

On the whole, this music is not far out. At its best, it sounds quite natural, wholly at one with its makers, unaffected, unmannered—a direct song, like all good music. It is not of the highest inspiration, but it is strongly felt music.

One must be careful not to expect thunderbolts. The new jazz is far enough along so that capable players can make coherent nontonal music at will. Anybody can do it who wants to, in fact. It takes no super-feeling, no super-talent, no super-training—just immersion and belief. I feel that there are hundreds of musicians who could have recorded Three Steps, although this may not be so.

Again, this is not a record of rare moments, but of everyday life-activity in which rare moments, naturally, occur.

The Logan disc has some of the best new jazz (from Pullen) and possibly some of the worst (from Logan).

Tabla begins with a texture dominated by the piano strings being plucked and stroked. This accompanies Logan’s laboring, wheezing oboe. The textures that this group has found are even less detailed, more coloristic than those of Byron Allen. The result is more hypnotic than musical and does not want repeated hearings. I ask more detail, more note choice, more thought. Some sections—the end of Taneous, for example—require different ears. There is a kind of LSD delight in the play of sound for its own sake. But music is more than that.

The prearranged material is bad enough to offend, in some cases revealing a simplistic and uncomprehending musicality. For instance, the return to E minor, in Bleecker, is simply not the way to organize this music. The cliched use of triads, modality, regular rhythms, endless melodic repetitions result here in a distortion of these conventional materials. This sense of willful distortion is at times so strong—as at the end of Dialogue—that one wonders what bizarre put-down is this of what by whom? If the music attempts this discomfort, it succeeds. Even if taken as exorcism—as in Satan—I wonder if Logan means to purge or enrage me. Perhaps these are the same? And maybe, too, I would feel less assaulted if Logan were a more accomplished player.

It is true, though, that one hears Logan’s overcoming of seemingly impossible obstacles. And one never questions his reality.

Pullen plays an exciting solo in Dialogue. His work is very rangey, very notey, yet he goes far beyond mere contour into an enormous hive full of life. He is not consistent enough, however, to lift Bleecker out of the pit.

Gomez has a terrific high sound. It’s hard to believe he isn’t playing a smaller instrument (he isn’t). He is a sensitive player, a good soloist.

Graves, a good drummer, does not shine here.

The Logan quartet is best in uncharted seas, and even there it succumbs sometimes to a rambling search just below the mark of musical survival.

Ayler’s music, like Logan’s, also contains distortion, but it is not a perverse force. And it is slightly wry, and slightly like Eric Dolphy’s saying, “Can you touch the beauty in this ugliness?”

Ayler makes a great wobbling noise. Notes disappear into wide, irregular ribbons, fragmented, prismatic, wind- blown, undetermined, and filled with fury. Though the fury is frightening, dangerous, it achieves absolute certainty through being, musically, absolutely contained.

Ayler seemingly rarely hears one note at a time—as if it were useless ever to consider the particles of a thing. He seems to want to scan all notes at all times and in this way speak to an expanded consciousness. And the consistency in this outpouring is a reference point from which his music takes shape.

The second variation of Ghosts contains a solo that has no counterpart in intensity except maybe in the best of Archie Shepp.

Murray is in evidence mostly through the very fast common pulse he lays down for everyone.

Peacock is of the finest, consistently creative; on Spirits he plays a wonderful solo.

All of Spirits is well shaped; in fact, it is the best musical experience to be found among these three records. In it the organization goes beyond the momentary detail. And Ayler sounds like torture here, but self-torture, an often desirable, or at least necessary, thing. Somehow he has us share it.

Ayler’s music, as well as most avant-garde music, is, at best, difficult to listen to. It is nevertheless a very direct statement, the physical manifestation of a spiritual or mystical ritual. Its logic is the logic of human flesh in the sphere of the spirit. Could it be that ritual is more accessable to some listeners than it is to others?

To those of us who think our brains are the center of the universe, this music will appear formless and antirational. The avant-garde is, in fact, rebelliously and stubbornly antibrain. When that repugnance of the brain goes away, the music will broaden.

Meanwhile, the musician asks: These men—are they real? Answer: Yes.

(B.M)

Bill Mathieu

*

Jazz Monthly (September, 1965) - UK

ALBERT AYLER TRIO—SPIRITUAL UNITY:

Albert Ayler (ten); Gary Peacock (bs); Sonny Murray (d)

New York City—July 10, 1964

Ghosts—First Variation : : The wizard : :

Spirits : : Ghosts—Second Variation

ESP Disk 1002 (45/3d.)

“ESP” IS A NEW American label started as a platform for the young avant-garde musicians of New York, and this particular release presents us with some of the most spectacular and intransigent examples of the new movement in jazz we have had in a long time.

Albert Ayler has worked with Cecil Taylor and seems to have absorbed a lot of Taylor’s approach; he has been leading his own band on record fairly regularly and has toured Europe with his group in the past year, though of course he didn’t play in this country. All this time he has been working in close association with Peacock and Murray, and the three of them have developed a remarkable singleness of purpose. I have been listening to Ayler’s records on odd occasions for some time now, and I think I can say that this present album is the most satisfying and comprehensive statement of his position yet. It won’t please everybody though. Ayler’s ideas seem to start with a rejection of all pre-set terms, in melody, harmony and rhythm alike and on all these tracks, after toying with a few paraphrases of his brief, simple, rather folky themes he plunges off with his colleagues into a pretty well uncharted area of total improvisation where everything, chord sequences, bar lines and melodic continuity, goes out the window in this quest for what I suppose is as well described in Ayler’s terms—spiritual unity—as any others. It’s a difficult and complex thing to attempt, and Ayler seems to care nothing for trying to make it immediately pretty either. He has a hard, strange tone and amazing speed on his instrument, though here again orthodox techniques are rejected in favour of a rather blurred, inexact articulation and pitch. Phrases relate to each other only against the background of the overall construction of the piece, in other words over the length of the track in the combined work of all three men.

All this, I realise, could be construed differently, and no doubt there will be shouts of Fake going up all over the place, but for what it’s worth my own opinion is that Ayler has made a considerable breakthrough in jazz. I am convinced he is no charlatan, and I hope soon to be able to examine his work at greater length than can be permitted in this section. For the moment it will have to be sufficient to say that there’s an awful lot happening on this record, not all of it easily intelligible either, but for anyone who feels that there must be branches of jazz that are rather more than just a sophisticated adjunct of the theatre and the bar if jazz is to have any kind of universal appeal this album is recommended as being well worth acquiring.

JACK COOKE

*

Jazz Journal (September? 1965)

The New Direction?

SPIRITUAL UNITY—ALBERT AYLER TRIO:

(a) Ghosts; First Variation; (a) The Wizard (13½ min)—(a) Spirits; (a) Ghosts; Second Variation 19 min)

(E.S.P. Disk 1002 12inLP 45s. 3d.)

PHARAOH—PHAROAH SANDERS QUINTET:

(b) Seven By Seven (25 min)—(b) Bethera (27½ min)

(E.S.P. Disk 1003 I2inLP 45s. 3d.)

THE BYRON ALLEN TRIO:

(c) Time Is Past; (c) Three Steps In The Right Direction (19 min)—(c) Decision For The Coleman; (c) Today’s Blues Tomorrow (24½ min)

(E.S.P. Disk 1005 I2inLP 45s. 3d.)

THE GIUSEPPI LOGAN QUARTET:

(d)Tabla Suite; (d) Dance Of’ Tatan; (d). Dialogue (18¼ min)—(d) Taneous; (d) Bleecker Partita (27¼ min)

(E.S.P. Disk 1007 12inLP 45s. 3d.)

In the final analysis, music must possess beauty. In this simple and somewhat platitudinous statement lies a fact that must remain uppermost when considering New Wave jazz. Although all of us are accustomed to the beauty of Armstrong, Hodges and Hawkins, there are many varieties. First reaction to the work of Thelonious Monk is proof enough. His angular line and unusual chords appear, on first hearing, to be its very antithesis yet, as the listener attunes to his language, he becomes aware of Monk’s quality and taste.

Similar adjustments must be made in listening to the music found on Bernard Stollman’s E.S.P. label. The four records reviewed here offer a wide range of styles, from a modal approach in the Coltrane pattern to the most ferocious type of free form. These records also draw attention to the very important fact that, while the free form jazz musician in search of harmonic freedom opens the doors to moments of great invention, he becomes more vulnerable to barren passages. His predecessor used the chord structure as the conversationalist uses grammar. It was the foundation on which all his extemporizations were built and, when inspiration failed, he had an immediate point of reference. No such refuge is available to the form player, who finds himself stranded if his stream of melodic creation dries up.

This fact is brought into stark relief on the album by the Guiseppi Logan Quartet. This talented reed player achieves an incredible pitch of emotion on Taneous and has moments on Bleecker Partita that are truly haunting. Too often, however, he runs short of inspiration as his solos develop and is reduced to repetition. Neither is this helped by his rather inflexible, emotional range or his pre-occupation with Indian music. As with several of his contemporaries, Logan fails to solve the problem caused by the resistance that many ‘eastern’ melodies have to European harmonies, leaving the player with an uneasy hybrid. This is apparent on Tabla Suite which features Logan on Pakistani oboe. It is an unhappy track and his phrasing is so stilted that the very pulse of jazz is lost. Even gifted, young drummer Milford Graves can provide no real lift.

Taken as a whole, this is a loose jointed combo and it is Pullen who contributes—on Dialogue in particular—the most impressive solo work. He is obviously influenced by Cecil Taylor and manages to achieve the same fierce attack and overall legato feeling. Behind the pianist, Graves provides a terse, rhythmic backing and their partnership is the highlight of a record that fluctuates alarmingly.

The Albert Ayler Trio is far more consistent. The leader is a very aggressive tenor player who already shows signs of true individuality. The sheer speed of his playing is an achievement and he creates fierce, sweeping phrases that have much in common with a cellist’s continuity of line. There is no lacking of swing, however, and he is aided in this by fine work from Peacock and Murray. Ayler uses the trio as a contrapuntal unit and I cannot recall a drummer whose part has affected his colleagues less. Yet paradoxically the three men sound far more unified than the Logan Quartet and the listener quickly finds himself oblivious of the component parts. The themes that Ayler has written for this album are strangely corny but a factor that will surprise many older readers is that, during the theme statements, his tone is reminiscent of Fess Williams. Ghosts has a specially trite melody but, like the remaining tracks, does not direct the subsequent solo to any great degree. Ayler attempts no real thematic development although there are moments when he plays related scales in the classic ‘sheets of sound’ Coltrane manner.

The Byron Allen Trio is more legitimately free form. The influence of Ornette Coleman is obvious and attention is drawn to the fact that Coleman is beginning to attract followers as prolifically as did Parker. Allen is one of the outstanding disciples and is obviously very serious about his music. Like Rollins he will not play simply for the sake of filling solo space and, because of this, his solos are prone to have in uneasy start while he achieves a conclusive direction. This is a good policy, for once in his stride he uses the affinity of thematic shapes as a structural bond and on The Time Is Past and Today’s Blues Tomorrow produces outstanding jazz. The former, in particular, features some fine playing at slower tempo. A great deal of the music on these four albums is taken at speed and this is not only Byron’s best performance but also a welcome contrast. The trio is also good. Maceo Gilchrist is a magnificent bass player and Ted Robinson a swinging and inventive drummer. They dovetail very successfully and one is reminded of Coltrane’s Blues To Bechet, recorded without pianist McCoy Tyner. Robinson heightens this effect by his Elvin Jones type rhythmic figures which serve Allen’s swaggering delivery perfectly.

The album by Pharaoh Sanders is a contrast to the remaining three. It gives the impression that the leader is faintly out of place in his own combo. Trumpeter Stan Foster, pianist Jane Getz and the remainder of the quintet function in an orthodox manner. Jane Getz, in particular, experiences the same trouble as did Walter Norris with Ornette Coleman. She provides all of the correct chords but there are many occasions when these clash with the alien harmonies that Sanders’ introduces for emotive reasons.

In spite of these seemingly damning reservations, this is a good album. There is only one number on each side and Sanders plays quite superbly throughout. His style uses elements of both Coltrane and Rollins. He favours the former’s extended examination of the material in hand and functions well in this modal style. There are moments, however, when sounds are used for their own sake and, at such times, the listener is reminded of Rollins in his present empirical mood. Both Seven By Seven and Bethera are good compositions by Sanders and in many ways this might represent the best introduction for the newcomer to this type of music.

Free form jazz has enjoyed a degree of blind acceptance in some circles and it is still difficult to apply durable standards. Although the jazz found on the E.S.P. label attempts to extend the concept of free blowing, it lacks the authority found in the music of Coleman, Taylor, Archie Shepp or John Tchicai. Nevertheless, all our young saxophonists have the ability to project a real and personal emotion in their playing. If there is a weakness it occurs in flaccid moments when everything is sacrificed for emotion. At these times of excess their playing is devoid of either beauty or purpose and it evokes an air of self consciousness that is hardly attractive.

In the main, however, there is a great deal of searing, passionate beauty to be found in these albums and their music fulfills most of the requirements of the jazz traditionalist. If it occasionally formulates its own standards we must not be surprised for this is jazz that, despite the example of Coleman, is still partly unsure of its ultimate aims. The records, available from most specialist shops at 45s. 3d. each, should be heard by all enthusiasts and I am sure that no lover of contemporary jazz would require the extra sensory perception, implicit in the label name, to enjoy the music they contain.

Barry McRae

(a) Albert Ayler (ten): Gary Peacock (bs); Sonny Murray (d) 10/7/64.

(b) Stan Foster (tpt), Pharaoh Sanders (ten); Jane Getz (p); William Bennett (bs); Marvin Pattillo (perc). 0/9/64.

(c) Byron Allen (alt); Maceo Gilchrist (bs); Ted Robinson (d). 25/9/64.

(d) Gluseppl Logan (ten/alt/Pakistani oboe); Don Pullen (p); Eddie Gomez (bs); Milford Graves (d). c. Sept. '64.

*

Coda (Dec. ’65 - Jan. ’66) - Canada

Spiritual Unity

ESP Disk 1002 M

The revolution that took place in jazz in the late fifties has given the music a possibility for a state of permanent change as each new artist with a capacity for self-expression emerges with a personal music. While Ornette Coleman’s views suggested great freedom for the improvising musician, his own music, in many respects, adhered to traditional practices. (This statement is made on the basis of Ornette’s recorded work which is now four years old. All reports suggest that he has grown tremendously in the interim. But these conclusions are not intended as an evaluation of Ornette’s music, but rather the affect that his stated ideas have had on musicians in their formative stages.) Though Coleman’s music, as any strong music will, has created ranks of imitators, his doctrines of freedom, which probably caused greater critical furor than the real content of his music, have given every musician an opportunity for a personal voice, an idea that critics who accept Coleman on the basis of “A jazz revolution every ten or twenty years” must surely find frightening. An example is pianist Cecil Taylor who has been performing longer than Coleman, but whose music has evolved considerably in recent years. Taylor is a musician capable of incredibly complex musical-emotional expression, quite beyond the original boundaries of Coleman’s own music. The repercussions of Coleman’s ideas can be seen in Albert Ayler, who, arriving only a few years after Coleman, is playing in a manner that few musicians and fewer critics could have imagined. His music can be described in a sense as a combination of Taylor’s and Coleman’s in that it combines the textural density of the pianist with the altoist’s use of timbres and pitches that have little to do with European formal music. The result is incredible.

The notes to Ayler’s first album (My Name Is, on Fantasy) quote John Coltrane to the effect that he had once heard himself sounding like Ayler in a dream but had never been able to produce it. This seems a good description of Ayler - an unconscious Coltrane, in that Ayler’s approach is multi-noted and moves in emotional realms usually untouched in art, though often reached for. But in musical, as well as emotional, terms Ayler is beyond Coltrane. While Coltrane hears and plays in terms of single notes, Ayler provides an outpouring of indivisible phrases, aural images that have almost tactile shape.

Like Taylor and Coltrane, Ayler plays a virtuoso music - music that demands control of the instrument in a personal direction. (It matters little whether Ayler is possessed of a “legitimate” technique (though I’m sure he is), for Ayler’s music is obviously contained - he plays clearly what he intends to play and playing things I doubt any other tenor saxophonist could touch - speed, range, sound, that are completely musical and completely beautiful. They are also absolutely his and since no one with any claim to sanity could ask an artist to do more than realize his vision with absolute certainty - which Ayler does, it doesn’t really matter it he can play like other people. (I am expounding on this for those who demand familiar terms of reference for a new artist, because they are unsure of their own faculties - their capacity to appreciate art, and to point out that - to the artist, their terms of reference are false, and reflect not on the artist but on themselves. Music tends to hold on to traditional references longer than other art forms because it is fundamentally an abstraction, devoid of natural references at the usual, superficial level of interpretation.)

Ayler’s personal technique as an artist, as opposed to a craftsman, is shown in the quantity of emotion conveyed to the listener in Ghosts, first variation. The listener however can be unconscious of Ayler’s accomplishment. I have heard the Ayler of this record compared to the Coltrane of Impressions, with the implication of sprawling performance. Yet Ghosts, first variation, the first experience to be registered as you play the record, is only five minutes long and that includes the fairly slow opening and closing statements, a bass solo, and a tenor solo that includes several textural changes. When I mention Ayler’s technique (facility, speed) I am not referring to the number of notes played (though this is almost without parallel in improvised music, the parallel being Cecil Taylor), but the amount of emotion perceived by the listener. I cited the brevity of Ghosts, first variation. I have several friends who play this record often and none of them complain of the shortness of side 1 (12 minutes) until it has been pointed out to them. Ayler has an incredible capacity for extending time by filling it so completely with music. In Ghosts he makes very swift emotional textural modulations that do not weaken the cohesiveness of the music, forming at will singular musical entities.

Similar events occur in the course of Ghosts 2, and this skill gives Spirits its beautiful structure. The Wizard is notable for its sustained intensity.

Ayler’s compositions serve an unusual role in his music. Ghosts and Spirits are like folk songs in their melodies, and drinking songs in their moods. (Ghosts is quite similar to the melody employed in TV commercials for Gallo wine. But Ayler has also employed Reveille and La Marseillaise in other records). In performance these melodies become absurdly broad in their humour while the subsequent improvisations seem insane (possessed) distortions of the melodies. Ayler may be trying to express everything with only simple melodic materials. If so, he is succeeding admirably. With these melodies, he also seems to be enacting the final exorcism of harmonic sophistication, and bringing an element of Beckett’s absurdity to music. The Wizard is a terse phrase which Ayler spits out four times, but at the end he tacks on a simple resolution that is hilariously effective when coupled with the rhythmic figure which he plays.

Ayler is well served by two accompanists who realize that Ayler’s momentum is sufficient to carry them (an unusual reversal of roles, also present in Taylor’s music. Traditional functions were obviously not formed with these two men in mind) and that their function is commentary. Sonny Murray sounds like breathing - pulse. A drummer prophesied in Billy Higgins’ best moments, Murray moves within his co-workers, Ayler and Gary Peacock, as a continuing sympathy.

Peacock has progressed at an amazing rate. In the past I have thought of Peacock as a very competent imitator of Scott La Faro, but the Peacock of Spiritual Unity has harnessed the cheap dexterity of old to a highly personal style. It would be impossible for the bassist to compete with Ayler on his terms of speed and volume, and Peacock carefully reforms the music to make strong emotional registrations of his own. There is an element of abstraction, a tension in his music, that one also hears in Tchicai and Cherry who have worked wtih this group on a Michael Snow film. Peacock’s rhythmic sense is now the strongest force in his playing, as he alternates sharp high phrases with buzzing low strings only to stop the open string while it is still vibrating with unusual care in rhythmic placement. This skill carries over to his accompaniments to Ayler.

The packaging, art work and photographs, is excellent, unusually imaginative. The liner notes take the form of a booklet, “Ayler, Peacock, Murray, You and the Night and the Music”, by Paul Haines, a beautiful document at once expressionistic and expository, certainly the most perceptive writing to ever grace a record.

Finding another record with the depth of expression, the music, of this one would be difficult. The music demands in return a depth of involvement unprecedented in the form, but its much more than worth it.

STU BROOMER

(used with permission, © Stu Broomer/Coda Magazine)

*

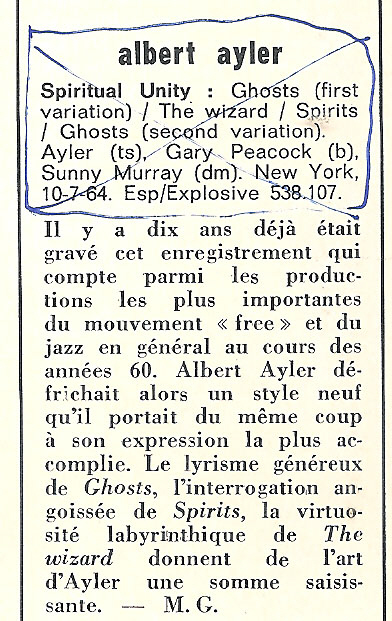

Jazz Magazine (No. 135, October 1966, p.55) - France

albert ayler

GHOSTS : Ghosts - Children - Holy Spirit - Ghosts - Vibrations - Mothers.

Albert Ayler (ténor et alto), Don Cherry (trompette), Gary Peacock (contrebasse), Sunny Murray (batterie).

Copenhague, 1964.

Fontana DEB 144 - 33 t - 30 cm.

____________________________________________________________________________________

SPIRITUAL UNITY : Ghosts (First Variation) - The Wizard - Ghosts (Second Variation) - Spirits.

Albert Ayler (ténor), Gary Peacock (contrebasse), Sunny Murray (batterie). New York, 1964.

E.S.P. (Monestier) 1002 - 33 t - 30 cm.

____________________________________________________________________________________

SPIRITS REJOICE : Spirits Rejoice - Holy Family - D.C. - Angels - Prophet.

Albert Ayler (ténor), Don Ayler (trompette), Charles Tyler (alto), Henry Grimes et Gary Peacock (contrebasses),

Sunny Murray (batterie). Dans «Angels», Call Cobbs (clavecin). Judson Hall (New York), 1965.

E.S.P. (Monestier) 1020 - 33 t - 30 cm.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Hymnes, sonneries, hurlements, marches et comptines, couinements, pleurs (d’enfants apeurés), prêches, ritourrnelles, et bien d'autres choses encore, il y a tout cela dans les enregistremcnts d’Albert Ayler — et l’on peut déjà dire qu’ils s’adressent à tous. A tous parce qu’ils ne contiennent aucun de ces médiocres messages d’origine restreinte et de portée limitée... Non, Ayler n’est pas un artiste «engagé»; il ne parle pas au nom des autres; il n'évoque pas leur silence ou leur fureur. Il lui suffit d’exprimer — avec les mots qu’il se forge — ses propres frayeurs. Et puis ses obsessions, fantômes actuels, fantômes-souvenirs. Différentes les unes des autres, quatre versions de Ghosts nous le montrent comme un aimable névrosé pour qui son saxophone et les rengaines les plus grotesques se transforment en instruments de sublimation. Espoir de surprises, poésie de l’instant et de la coïncidence, refus de prouver, d’affirmer ou de convertir, et, du même coup, naît une musique totale parce que délivrée de toute utilité. Une rnusique, enfin, qui ne veut rien dire. Une musique, en tout cas, de divertissement.

Mais d’autres musiciens sont là, autour d’Ayler, à ses côtés ou derrière lui. Don Cherry, par exemple (Ghosts), qui ajoute à l’ensemble un lyrisme presque incongru, une poésie autre, un élément contradictoire. Et ce Call Cobbs, qui joue du clavecin (!) dans Angels (Spirits Rejoice), qu’est-ce, sinon un instrument de confusion? Avec soin et joliesse, il improvise des phrases mièvres, choquantes, et semble loin, très loin, ailleurs, apparaissant plutôt comme le résultat d’une hallucination auditive, comme un rêve, celui d’Ayler lui-même qui se débat ou cherche à le rejoindre. La musique qu’il joue, sa nature même, sa situation au regard des autres musiciens, tout est prévu pour le laisser à l’écart, catalyseur et non-acteur. Essentiels, en revanche, apparaissent les contrebassistes, véritables héros de l’aventure aylerienne. Partout, sans cesse, on les entend. Les cordes sont frottées, grattées, pincées, caressées, tordues, détendues, nouées, et Gary Peacock s’impose, qui n’est plus seulement un disciple de Scott LaFaro, mais un des plus grands inventeurs de sons et de mélodies sur cet instrument presque roi aujourd’hui. En duo, avec Henry Grimes, son jeu tout en velléités lyriques ne laisse pas d’évoquer le dialogue LaFaro-Haden (Ornette Coleman, Free Jazz). C’est dans Spiritual Unity que son rôle semble le plus décisif, le plus évident. L’unité y est atteinte, d’emblée, effaçant la notion de trio. Quel que soit, d’ailleurs, l’enregistrement, Peacock s’y découvre eomme un partenaire idéal d’Ayler, le seul sans doute capable de lui répondre avec lucidité, le seul qui puisse apaiser ou préciser sa panique en forme de vibrato. Et puis, dernier sommet du triangle, il y a Sunny Murray qui enveloppe l’ensemble de ses chocs et se glisse entre les sonorités dominantes. Avcc une douceur inouïe, il montre que les tambours et les cymbales de ce jazz-là ne sont pas toujours synonymes de terreur ou d’explosion. On lui doit plutôt de donner à la conversation basse-saxe une dimension nouvelle; d’une figure plane, il fait un volume diffus et sans cesse agité de mouvements internes. Il provoque, gêne, contrarie ou trouble, renchérit, ou s’efface soudain afin de souligner. Souvent, même, il parle d’autre chose, de lui, en un complexe contrepoint; jamais il ne dit «chabada», et sans doute serait-i1 incapable de jouer comme certains batteurs plus illustres que lui: son défaut est de ne pouvoir jouer que comme Sunny Murray. Sa manière «chaotique», au-delà de la tradition, de l’experience (des autres) et du souvenir, est un moyen de n’être que lui-même.

Ce trio, on le voit, refuse le passé — celui des autres — afin de mieux actuaIiser les émotions (et non les leçons) de son enfance. On a dit d’Ayler que ses premières manifestations publiques eurent lieu aux cours d’enterrements. Là, aux côtés de son père, il découvrit les fanfares, la peur de l’inconnu (Ghosts, Spirits), un espoir de douceur et de consolation (Angels, Mothers), le mystère (The wizard). Sa musique, aujourd’hui, reste celle d’un enfant et son plus bel enregistrement n’est-il pas celui qu’un poète américain a sous-titré ainsi: You, the night and the music (Spiritual Unity) ?

Certains se posent la question: Ayler est-il un fumiste? Mais «il n’y a, comme l’écrit E.M. Cioran, que l’artiste dont le mensonge ne soit pas total, car il n’invente que soi.»

— P. C.

Back to Record Reviews: Ghosts or Spirits Rejoice

*

Jazz Hot (1966 ?) - France

SPIRITUAL UNITY

Ghosts, first variation • The wizard •

Spirits • Ghosts, second variation.

ESP 1002 (30 cm - 29,90 F) ****

Albert Ayler (ts); Gary Peacock (b); Sonny Murray (dm). New York, 10 juillet 1964.

SPIRITS REJOICE

Spirits rejoice • Holy family •

D.C. Angels • Prophet •

ESP 1020 (30 cm - 29,90 F) ****½

Don Ayler (tp); Albert Ayler (ts); Charles Tyler (as); Henry Grimes et Gary Peacock (b); Sonny Murray (dm); Call Cobbs (clavecin sur “Angels”). New York, Judson Hall, septembre 1965.

Albert Ayler dérange parce qu’il empêche les gens d’être intelligents. Sa musique parait demander une coopération, une interprétation au public — ce qu’on ne s’est pas empêché de faire à Paris — comme si elle était trop limpide et nécessitait l’obscurcissement critique. Tantôt naïf (“douanier Rousseau”, Malson), tantôt dérisoire (“Samuel Beckett”, Wagner), tantôt ridicule (“Médrano”, Ténot), tantôt dangereux (“Hargne raciale”, Koechlin), tantôt vulgaire (“le caca”, Gilson). Personne ne sait qui il est. Lui non plus. Sa musique est vraiment trop simple. Puissent ces deux disques trouver l’écho qu’ils méritent, surtout “Spirits Rejoice” captivant d’un bout à l’autre, très varié (la Marseillaise, une pièce pour clavecin et un morceau de rock and roll); le climat de “Spiritual Unity” apparait curieusement plus abstrait, vraisemblablement parce que la formule du trio aboutit à une interaction plus profonde qui doit, pour être véritable, et c’est le cas ici, s’établir sur plusieurs registres. II y a de “Unity” à “Rejoice” un pas important qui ne tient pas tant à la nature de soliste d’Albert Ayler qu’à une conception musicale en constant renouvellement. Les critiques qui sont faites à Ayler dénotent la plupart du temps une position d’accusé; elles lui prêtent, au-delà de la musique, plus d’intentions qu’il n’en a véritablement. Les improvisations linéaires des frangins, on s’y habitue vite et on a le temps de penser à ce qu’on va dire quand ils auront fini. Par exemple une tentation surréaliste, qui ferait du jazz un spectacle. Mais là encore c’est signaler sa présence et sa culture d’auditeur européen plus prompt à faire jouer des mécanismes d’éducation, à confronter les idées reçues aux nouvelles qu’à faire effort de compréhension véritable même si les données du problème Ayler sont difficiles à découvrir et même si elles sont à inventer.

Essayer de prendre le personnage avec toutes sec caractéristiques? Originaire de Cleveland, c’est-à-dire du ghetto de Nough où la guerre raciale éclate chaque été, de famille pauvre, Al Ayler a dû décider un jour, comme ça, qu’il deviendrait le plus grand saxophoniste de jazz, un peu comme Cassius Clay le plus grand boxeur. Il a tout mis en oeuvre, par tous les moyens. D’abord conquérir New York, jouer avec les plus modernes, Cecil Taylor en tête, ne pas se laisser avoir, ni par les Blancs ni par les Noirs ; ensuite trouver un truc infaillible (il avait déjà plus d’un tour dans son sac: plus de phrasé détaillé tout en restant près de l’harmonie, une grande insistance sur les agglomérats sonores, etc.) et il crée ses “themes”, peut-être en Europe. D’ailleurs les Américains réagissent tout à fait différemment devant “Ghosts” ou “Spirits Rejoice”, eux qui ne connaissent pas “En passant par la Lorraine” et dont les fanfares municipales diffèrent sensiblement des nôtres. Les amateurs de jazz seraient-ils devenus si fatigués à l’heure de la nouvelle figuration pour ne pas participer à un spectacle musical qui prendrait racine dans une musique campagnarde dont les éléments nous sont si familiers depuis l’enfance qu’on y est depuis longtemps indifférent? Enfin c’est la période ESP, avec “Bells”, en public, point culminant. Ornette Coleman n’a qu’à bien se tenir. Al s’ennuie à Cleveland mais dès qu’il vient à New York il a envie de rentrer car “les gens sont vraiment trop pleins de haine”. Il semble que sa carrière internationale soit plus qu’amorcée.

L’image qu’il donne de lui-même varie entre l’apôtre évangélique prêchant la paix des âmes (We play peace), le gars de campagne rusé, finaud, presque opportuniste, conscient de son pouvoir d’impact sur le public, et le musicien d’avant-garde qui a tout inventé, maudit, constamment exploité et méprisé. Dire que toutes ces impressions se dégagent de sa musique serait tenter une exégèse; mais supposer que ses préoccupations sont d’ordre “esthétique” au sens où nous l’entendons, c’est-à-dire réflexion sur un ordre, une hiérarchie de valeurs abstraites, en est une autre, encore plus audacieuse.

Curieux le manque d’écho et d’influence de sa musique? A New York Frank Wright, beatnik blanc barbu et chevelu, beaucoup plus près des Fugs ou du Living Theater que de la musique des Noirs (*), et qui selon Le Roi Jones “vole” la musique d’Ayler; à Paris, Portal qui joue “Ghosts” avec Vitet comme affirmation de son avant-gardisme, prêt à toutes les expériences, caricaturise ce qui est déjà caricature. Ayler ne peut qu’avoir une influence épisodique car il ne rénove en rien la pensée musicale du jazz. Oui c’est un soliste d’exception, que Coltrane et Cecil Taylor tiennent en haute considération, qui a libéré bien des idiosyncrasies, a favorisé bien des renouvellements dans l’improvisation, a découvert bien des ressources, et aussi encouragé bien des snobismes. Oui, à ce niveau Ayler est d’une importance extrême et ses tempêtes auront apaisé bien des consciences. Il a apporté, peut-être avant Coltrane, une fantastique leçon d’énergie, fondamentalement nécessaire, régénérant les bases de l’idiome-jazz. En cela chaque saxophoniste qui commence son chorus lui est redevable; comme lui il essaiera de jouer comme si ce devait être la dernière fois. Mais ce n’est pas sur cette démence dans l’expressivité, sur cette énergie qu’il faut s’interroger mais sur sa direction et sur ses fondements. Est-ce parce que cette musique contient sa propre contestation qui nous fait nous interroger sur son utilité? Alors aurait-on un sentiment de gratuité, d’autant plus inquiétant qu’il serait contradictoire avec le besoin qui a donné naissance à la musique, ou de régression dans l’imagination musicale qui peut paraitre primaire et sans susceptibilité de varier de registre? Mais peut-être qu’un jour Ayler deviendra un vrai révolutionnaire, un Garde Noir, et ira chercher son inspiration dans le jazz, le “vrai”, ce qui après tout ne serait pas un comble.

Daniel Berger

Back to Record Reviews: Spirits Rejoice

*

Musica Jazz (1967(?)) - Italy

LP da 30 cm. - “Spiritual Unity”

- ESP/DISK 1002 (Distr. Bluebell).

L. 2400 + tasse.

Albert Ayler (ten.), Gary Peacock (cb.), Sonny Murray (batt.).

New York, 10 Iuglio 1964.

Ghosts: First Variation

The Wizard

Spirits

Ghosts: Second Variation

La distribuzione in Italia di questi dischi, che avviene con molto ritardo rispetto all’annuncio dato nell’ottobre dello scorso anno, è comunque un avvenimento di grande importanza. Negli ESP è contenuta una buona parte del jazz di stretta attualità, e chi voglia tenersi al corrente non li può ignorare: basti dire che il catalogo comprende, tra gli altri, i nomi di Ornette Coleman, Paul Bley, Giuseppi Logan, Bob James e Sun Ra.

Albert Ayler, sotto un certo aspetto, è forse l’uomo di punta di questa pattuglia, se si ammette che una simile definizione, al limite cui si è giunti, abbia ancora un senso. La sua musica, come ha ben detto Alberto Rodriguez, si pone deliberatamente contro il razzismo della società bianca: è una musica che vuole essere ascoltata “non come ricreazione o relax, ma intenzionalmente come fastidio e disturbo”. Per questa via, i suoni ch’egli costruisce possono giungere a far male “quasi fisicamente” ed a conseguire una “inorecchiabilità totale”. Una sua affermazione, riportata anch’essa da Rodirguez, va particolarmente raccomandata alla meditazione degli amatori di jazz, perchè pone per via indiretta un interrogativo al quale, in un futuro abbastanza prossimo, bisognerà pur dare una risposta: “C’è la musica e ci sono gli esseri umani. Questo è tutto. Io non suono jazz. Mia madre non ha messo al mondo un musicista di jazz, ma un essere umano. Questo è ciò che io suono: musica umana”.

Ciò posto, è evidente che quando Ayler incise, tre anni or sono, il microsolco in esame, si trovava press’a poco sul palo di partenza. In questi brani s’intravvede ancora un’architettura, perfino un’esposizione tematica chiara, ed Ayler ha una bella voce strumentale ed una tecnica superlativa, e i suoi compagni collaborano con lui su un piano di parità, intrecciando un dialogo continuo e serrato. L’audizione di “Spiritual Unity” va vivamente consigliata: a chi capitasse di ascoltare senza preavviso le più recenti fatiche di Ayler, potrebbe venire il dubbio che il saxofonista non sia capace di suonare. Se non sbaglio, a suo tempo si usava una terapia analoga per chi pensava di mandare Picasso a scuola di disegno: lo si prendeva per mano e lo si portava davanti ad un quadro del periodo rosa.

Franco Fayenz

*

Jazz Monthly (No. 179, January 1970) - UK

SPIRITUAL UNITY:

Albert Ayler (ten); Gary Peacock (bs); Sunny Murray (d)

New York City — July 10, 1964

Ghosts (First variation) :: The wizard :: Spirits :: Ghosts (second variation)

Fontana SFJL933 (28/7d.)

AN AVANT-GARDE classic re-released at give-away value! Or a classic give-away of avant-garde values? If I’d never heard ESP-Disk 1002, I might think that the 5 seconds of electronic whistle 10 mins. 10 secs. after the start of Side two was a neo-avant-garde embellishment, but perhaps it’s just been inserted on my copy to see if my attention had wandered. It hadn’t but the rather obvious fact that the music is easier to follow than five years ago doesn’t increase its value, so the fence I’m sitting on must have moved.

This being said, any attempt on my part to review this record will tell more about me than about the record (but, if you want to take the plunge and find out, you may be relieved to learn that it only lasts 29½ minutes). First of all, I have no use for any mystique surrounding this or similar music, despite the LP title — the entire sleeve-note consists of the words “The symbol “Y” predates recorded history and represents the rising spirit of man”. Well now, I always understood it to be a primitive representation of the female sexual organ and, since any music worth assessing by jazz criteria should have a strong erotic content, the rewards here are disappointing. On this level, Ayler sounds like an impotent exhibitionist compared, for instance, with his source and inspiration Sonny Rollins. And on a rhythmic level (which is obviously closely connected) Ayler shows here, as in his latest LP of alleged rock-and-roll, that his sense of timing is more — shall we say — elastic than his accompanists! And the lack of variety or — shall we say — singlemindedness which causes him to quote from Ghosts during Spirits and from The wizard during Ghosts 2, limits him emotionally. The only thing that worries me is that the last two sentences also applied to the few men who have been accepted as major jazz innovators; whether this category will include Ayler depends solely on the consensus of practising musicians, so don’t write to me about it.

BRIAN PRIESTLEY

*

Jazz Magazine (No. 220, March 1974) - France

|