|

ALBERT AYLER

HOLY GHOST: RARE & UNISSUED

RECORDINGS (1962-70)

REVENANT 9XCD

To all the worshippers in the Church of Albert Ayler, the holy rollers and the bug-eyed acolytes; to all the neophytes and sceptics, the critical naysayers and money lenders, listen up: the tablets just came down from the mountain.

Many moons in the making (ever since Dean Blackwood and the late John Fahey established the Revenant label back in 1996, in fact, with a dream to release a series of unanswerably heavyweight documents that would rescue the reps of some of the heaviest, but most marginalised, American musicians of all time, from Charley Patton to Cecil Taylor), Holy Ghost is an attempt to construct a “monument in sound”, as the packaging states, to a musician who built an entire new universe from sound, one that seems to expand rather than contract the further you travel into it, that becomes less knowable the more familiar you become with its cosmology. Which is to say that while Albert Ayler in our time is without doubt the most charismatic and mythologised jazz (let’s call it that, for the sake of convenience) musician of his time, he is also the most ineffable, the least tangible, his music the most cryptic, even now, three decades on from his death in 1970, and even as his own pronouncements on it in his own time seemingly made it the most straightforward. Compared to the kind of spiritual and intellectual fence-sitting that ultimately damned the lysergic philosophy, crackerbarrel mysticism and blissed-out universalism that underpinned, or were bolted on to, much of the music of his time, black and white, the spiritual and political messages in Ayler’s music were crystal clear. As he once wrote, referring to a vision he had of himself and his trumpet-playing brother Donald running from flying saucers, “It was revealed to me that we had the right seal of God Almighty in our forehead”; and in his own mind the music he made was nothing less than a channel through which Man would hear the Word of God. Simple. Except it wasn’t, of course. For Albert, and for us, that clear signal was compromised, jammed and distorted by the fact that he was living and working during the era of Vietnam, civil rights, the be-in and the happening; his singular music co-opted, often by forces outside his control, into both the multikulti hippy culture then emerging from New York’s downtown East Village (check the sub- Rick Griffin artwork with which his first Impulse! recordings were packaged) and the essentialist programmes of the Black Arts movement based way uptown in Harlem. But mainly, the message was garbled beyond all understanding because Albert Ayler also happened to be one of the most advanced musical minds on the planet, dreaming up new techniques and extending established musical practices into uncharted realms in order to play a Holy other kind of blues (which is why he wasn’t, for instance, Vernard Johnson, the ‘Soul Winner’, a gospel saxophonist whose music reverberates with the same kind of ecstatic dementia that animates Ayler’s own playing, but which is couched entirely in the vernacular of the Pentecostal church). And it is at a unique point, somewhere between the twin imperatives of delivering the ancient redemptive message and striking the aesthetic advance, that Ayler’s music churns and writhes, sucking us in as it attempts to resolve the multiple tensions contained within it: between purity of form and expression; truth and freedom; collective effort and individual ego; cosmic transcendence and physical limitations; political manifesto and religious exegesis.

And so it goes with Holy Ghost, whose contents are housed inside a biscuit-tin sized “spirit box” moulded from black plastic and inscribed with markings that are possibly of Islamic origin, although there are no clues as to their possible significance. Some of those contents are pure ephemera: a mundane message scribbled on a piece of hotel notepaper, a pressed dogwood flower, a flyer for an appearance at the notorious New York jazz dive Slug’s Saloon. These are holy relics, significant only because they are facsimiles of things once touched by Ayler’s hand, as opposed to carrying any clues as to the quality of his presence, the nature of his vision, the methods he developed to realise it, or the cataclysmic decisions he took regarding his music in the short time - just eight years - that he had to document it.

Attempts to address some of those pressing concerns are made in the series of essays (biographical, myth-poetic and polemical), witness statements and affidavits, musicological investigations and discographical arcana that make up the 200 page clothbound hardback book at the centre of the box. Strangely, the book devotes most space to Marc Chaloin’s blow-by-blow account of the time Ayler spent in the suffocating embrace of the Scandinavian jazz community in the early 60s after he’d left the army, and only addresses in passing the crucial question of what might have been going on in his head when he made drastic changes to the shape of his music while at the height of his creative powers in 1965 and then again in 1968.

And finally, there at the bottom of the box, in a recess like a priest hole, are the tablets themselves, nine discs containing seven hours of music and two hours of interviews and conversation, all taped between 1962-70, between Albert Ayler’s first and last documented recordings. (Most surreal moment on the interview discs: Ayler fingering Tom Jones for ripping off one of his tunes.)

It should be noted that some the music here has been heard before, albeit for the most part in inferior or misleading editions: the 1964 live recordings taped by poet Paul Haines at the Cellar Cafe in New York with bassist Gary Peacock and drummer Sunny Murray, and the Copenhagen recordings made the same year by the same trio augmented by trumpeter Don Cherry; as well as the 1966 live tapes made in Berlin with an entirely new group. It should also be noted, however, that the ‘familiarity’ of this music doesn’t diminish its impact one iota. Even now, being fully aware of all the extensions to Ayler’s original concept of a free spiritual music that have been made over the past four decades, often by individuals far removed from the traditions that fed into that concept, it still sounds utterly unique, utterly compelling, simultaneously familiar and alien. But for this acolyte, at least, the most compelling passages in this particular book of revelations lie elsewhere.

The first music we hear was made in 1962 in a Helsinki radio studio in the company of a group led by local guitarist Herbert Katz. The repertoire consists of Ayler’s favourite jazz standards, “Summertime”, “On Green Dolphin Street”, “Sonnymoon For Two”, and Katz’s quartet play with the kind of drop-dead cool, small hours insouciance that was defined for all time by Miles Davis’s group on Kind Of Blue; a music that responds to the weight of the emotional world by shrugging immaculately tailored shoulders deep in the urban night. Such an aesthetic couldn’t have been further removed from Ayler’s, who was already extending the kind of complex saxophone language that Sonny Rollins had developed out of similar material into a realm where it was starting to lose its earthly shape, the lines morphing at their outer edges into strange, ectoplasmic emanations. The music that follows these three short pieces consists of a 20 minute performance made for Danish TV for which Ayler sat in with The Cecil Taylor Unit featuring Sunny Murray and saxophonist Jimmy Lyons. And although it was taped just five months later, the intellectual, emotional and sonic realms it describes feel light years distant. In fact, what has happened is that Ayler has found himself teleported into a dimension where everything, from the molecular level on up, is unutterably different from anything he has experienced before, and yet what’s strange is that this new dimension feels intuitively right. The universe represented here by the 1962 Helsinki recordings is primitive, carbon-based and ruled by the pull of gravity. But the Taylor Unit revealed to Albert a new context, a new way of being free from the kind of physical laws that pulled music back to earth, impeding its transcendent ascent to the heavens and back. For Albert, the revelation was all contained within the simultaneously complex and intuitive interplay between Taylor’s chromatic pianism and the patterns Sunny Murray conjured from two drums and a cymbal, an approach to jazz-time that, as Val Wilmer has put it, made rhythm lose its meaning; or put another way, with Murray behind the kit the material reality of jazz-time suddenly collapsed into anti-matter relativity. This was the equation Albert had been searching for to prove his own tacit understanding of the jazz equivalent of Relativity Theory, and it was one he applied to the music he would produce with the groups he led featuring Murray throughout 1964, the aforementioned examples of which dominate the first two discs here.

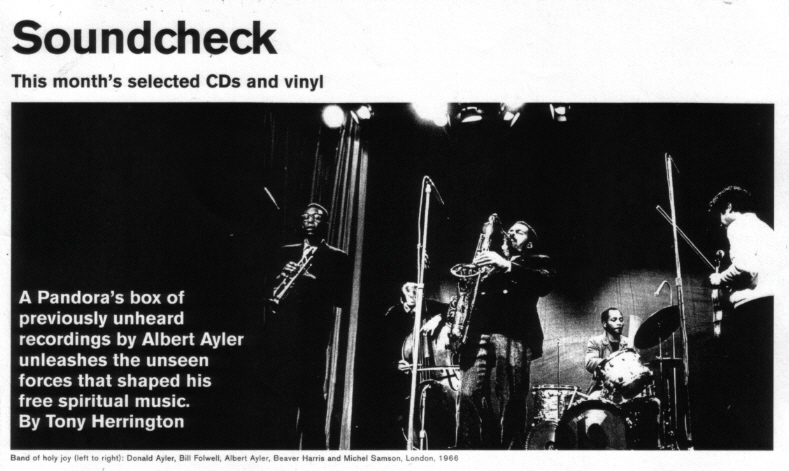

The third and fourth discs contain two recordings of a new Ayler group taped at La Clave, a folk music club that would later host some of The Velvet Underground’s most legendary sets, in his hometown of Cleveland, Ohio on 16 and 17 April 1966, and hearing these performances back to back with those taped two years earlier it feels like a shift of seismic proportions has occurred in the conceptual designs and constructions of the music. It wasn’t that way in reality, but unfortunately there is no music here to complement that already archived on the Spirits Rejoice and Bells albums, both taped in 1965, which documented the slow dissolution of the ideas the saxophonist was working through in the 1964 trio and quartet, and the formulation of a new approach to his group music, one that was forced on him, as Holy Ghost's compiler Ben Young suggests, by the eventual departure of Peacock and Murray, and the need to accommodate a number of very different forces that were introduced into the music. Those forces included a parade of different drummers, beginning with Ron(ald Shannon) Jackson and continuing with Beaver Harris and Milford Graves, all of whom responded to the challenge of Ayler’s new blues by putting the funk back in it (that is, the very stuff that had been sucked out by the vacuum caused by Murray’s knitting-needle rhythms); as well as Albert’s brother Donald, whose role was to lead the new ensemble parts, laying out the monumental, hymnic themes of new compositions such as “Our Prayer”, while violinist Michel Samson, a Paganini for the ESP set, spun thick webs of harmonic expansions and inversions, creating a new atonal centre within the music.

But here at least, the La Clave recordings are where Ayler first begins to make overt the links between his concept of group music and a reconfigured model of that which ruled in the cradle of jazz, New Orleans, at the turn of the century. And how bizarre is that, in New York City in the mid-60s, the absolute apex, geographically and temporally speaking, of American modernism? That the most revolutionary musician of his generation should suddenly turn away from the breakthrough concepts he has made in the company of some of the other most radical musicians of the time, to frame, or contain, his signature sound within a structure that, were it a photograph, would be a dog-eared image of a sharecropper standing in front of a ratty wooden shack on some Godforsaken Deep South cotton plantation?

But if elements of this music felt sepia-tinted, it was all simultaneously coated with thick layers of cosmic dust. Just as Ayler’s solos draw a line connecting the raw vocalised cry of R&B saxophonists like Illinois Jacquet with images of 31st century Afronauts feeling the spirit in the temples of a sanctified Alpha Centauri, on the La Clave recordings Jackson’s drums tear a wormhole in time, shifting the location of the music dramatically up and down what Amiri Baraka would refer to as the changing same of the Afro-American blues continuum. Prefiguring his later work with Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman’s Prime Time and his own Decoding Society, Jackson reroutes the kind of parade ground snare drum rhythms laid down by Paul Barbarin on The Young Tuxedo Brass Band’s 50s recordings of traditional New Orleans funeral dirges and march themes, and the syncopated proto-fonk patterns developed out of Barbarin’s rhythmic innovations by Earl Palmer, through a mindset permanently altered by exposure to the multidirectional polyrhythms developed by Elvin Jones and Rashied Ali in John Coltrane’s groups.

Listening to the collectively improvised passages on the La Clave versions of “Truth Is Marching In” and “Zion Hill”, the “dense, multiple erupting thicket of sound - and feeling”, as Nat Hentoff once put it, you instinctively grasp what Donald Ayler was getting at when he gave instructions on how to listen to this music: “[Don’t] focus on the notes. Follow the sound, the pitches, the colours, you have to watch them move.” And from there it is just a short leap of the imagination to understanding how this music, heard in exactly that way, could feed into the mentality of an entire generation of autodidactic outsiders, from The Blue Humans to The Dead C and beyond, who had little purchase on the kind of black music traditions that Ayler’s music connected with, however obliquely, but knew of the potential for revelation through noise.

Ron Jackson’s out of time (in both senses of the phrase) approach to jazz rhythm was abstracted to the nth degree by Milford Graves, as demonstrated on two of the great finds of this set, a recording of the Ayler group’s appearance at the Newport Jazz Festival in July 1967, and a tape of its performance at John Coltrane’s funeral just three weeks later (the fidelity of this latter tape is beyond lo-fi, but when Albert starts to scream-sing towards the end of the six minute medley of “Love Cry”, “Truth Is Marching In” and “Our Prayer”, the emotions being expressed couldn’t be more clear had they been taped in 24 bit digital surround sound). On the Newport recording, Graves’s drums are so far forward in the mix they sound like the lead instrument, carrying the rest of the group in their wake, rather than driving it on in the style of Jackson. But on the version of “Our Prayer”, it is Ayler who grips the imagination. Here he plays alto, and transposes the pitch of the instrument into the knife-point attack of a ney or shenai. But he moves this needling sound through such extreme registers that the fidelity, the envelope of the recording, is barely able to contain the expanse of the soundfield staked out by what might be the most amazing section of music he ever produced.

From here Holy Ghost tracks the slow dissipation of Ayler’s music through the last two years of his life, via previously unheard demos for the notorious 1968 Impulse! ‘crossover’ album New Grass, which, despite Ben Young’s comments in the track notes, sound as wack as the actual record, and are even more lame than Archie Shepp’s contemporaneous efforts to get on the good foot; and an informal performance recorded in the South of France in the summer of 1970, which finds Ayler coming full circle, working with a new group of musicians that are so far behind him in terms of his musical conception it’s like hearing Jimi Hendrix jamming with The Dave Clark Five. This period of Ayler’s life, both personal and musical, even now follows a perplexing narrative, elements of which the saxophonist elaborates on during the two long interviews contained on the final two discs that were conducted in the South of France also in the summer of 1970, and which are full of philosophical queries, ontological investigations, spiritual prognostications and digressions on the logistical problems he had in diffusing his music via the kind of record company machinations that had diverted and distorted the course of black music ever since the dawn of phonography.

But then, dropped in among these tawdry epistles, a revelatory document. In January 1969, Albert reconnected with his estranged brother Donald at New York’s Town Hall in a group led by the trumpeter that was modelled on the one Albert had abandoned the previous year. Of the two pieces from that concert included here, the first, “Prophet John”, sounds like some kind of summation (as early as 1964 Albert had been announcing, “I’ve been feeling the spirit for some time now; already it’s getting late”) and might just be the most apocalyptic ten minutes of music ever recorded. The opening trumpet fanfare is levelled in the direction of Jericho, and the rest of the track, a cataclysmic combination of ferocious percussion onslaughts from drummer Mohammad Ali, whooping sounds of alarm from the saxophones of Ayler and Sam Rivers, and massive distortion caused by the inadequacies of the recording device, sounds like the walls themselves being razed to the ground.

Writing in March 1967 in International Times, Ayler wrote: “The only way I can thank God for His ever-present creation, is to offer Him a new music imprinted with beauty that no one, before, had heard.” Here is some of that music. For all to hear.

*

Creem Magazine (November, 2004) - USA

Albert Ayler: Holy Ghost

By Brian J. Bowe

When saxophonist Albert Ayler died in 1970, his obituary in Down Beat said his playing "bore little resemblance to any other jazz, past or present." And 34 years later, his playing is still unlike anyone else's. A new box set, Holy Ghost, provides more evidence of that than anyone should need.

The folks at Revenant are known for their lush packaging, and Holy Ghost is no exception. The box (which is a gorgeous spirit box cast from handcarved original) contains 10 CDs of rare and previously unreleased recordings. Along with the discs comes a 208-page full-color hardbound book featuring new essays by Amiri Baraka, Val Wilmer, other Ayler scholars. It also comes with sacred Ayler relics (a small flower in an envelope, reproductions of photos and letters, and some reprints of the great literary chapbooks published during the his time and featuring some of his contemporaries).

The recordings are drawn from radio and TV sessions, studio demos, private recordings, and live concert footage, all of which give testament to the breathtaking breadth of Ayler's talent. His saxophone playing featured extreme vibrato, powerful playing around the melody (although sometimes returning to the melody). It's like a high-energy New Orleans funeral march or klezmer music from Space-Africa.

In many ways, his playing comes off as the logical extension, the next step after John Coltrane (although the influence went both ways between those two giants). With titles like "Spirits Rejoice," "Free Spiritual Music" and "Judge Ye Not," the music has an overtly holy bent, drawing from spirituals but taking them to new levels of Pentecostal outness (as though Ayler was playing his saxophone in tongues). It reeks of spiritual and physical liberation, and it helps cause feelings of both.

Not only was Ayler a jazz innovator, though. He was also one of the prime influences on the MC5 - an influence that can be easily heard when Ayler's work is compared to MC5 improv freakouts like "Black To Comm" or "Starship."

In the accompanying book, there's an account of a conversation between poet Ted Joans and clarinetist Albert Nicholas that shows why the Five found Ayler's approach so appealing.

"I turned to say something to Albert Nicholas," said Joans of an Ayler performance with Don Cherry, Gary Peacock and Sonny Murray. "And then like an unheard of explosion of sound, they started. Their sound was so different, so rare and raw, like screaming the word 'FUCK' in Saint Patrick's Cathedral on crowded Easter Sunday…The entire house was shook up. The loud sound didn't let up. It went on and on, growing more powerful as it built up. It was like a giant tidal wave of frightening music. It completely overwhelmed everybody."

Holy Ghost is overwhelming, too. It's overwhelming in its size, its breadth, its packaging, and its price. But really, it's a small price to pay for salvation.

*

Coda (No. 318, November/December 2004, p. 16-19) - Canada

AYLER RESURRECTED,

A LOOK INTO REVENANT’S

ALBERT AYLER: HOLY GHOST

BY ART LANGE

The mysterious circumstances surrounding Albert Ayler’s death in November 1970 have never been solved, though his legend—focusing on the enigmatic intensity of his music and the reputed spiritual purity and innocence of his message and motivation—has increased in stature to the point where he is now considered the patron saint of pure-sound Free Improvisation, with disciples as stylistically, conceptually, and generationally diverse as Roscoe Mitchell, Peter Brötzmann, and Mats Gustafsson (among a host of others) continuing to spread their vision of the Word. Acknowledged as one of the most iconoclastic (and according to his detractors, nihilistic) forces within the turbulent jazz world of the 1960s, which often took inspiration from and simultaneously fed back into the radical political and social climate of the time, Ayler recognized the power of his music, even if he seldom knew how to wield it effectively, and he identified the musical (and implicitly spiritual) relationship between himself, John Coltrane, and Pharoah Sanders in a famous statement: “Trane was the father, Pharoah was the son, I was the holy ghost.”

Revenant Records has adopted this quotation as the symbolic creed of its lavish, nine-CD boxed compilation, Albert Ayler: Holy Ghost (RVN 213): included among the ephemera—a replica of a handwritten postcard, a photo of the child- prodigy saxophonist, a reduced-size poster from Slug’s, and booklets of related material—is a small plastic envelope holding four pressed petals from a dogwood tree, the tree from which, it is said, Christ’s cross was cut (though the suggestion of Ayler as martyr actually mixes their metaphors, since the Holy Ghost was/is believed to be incorporeal spirit, without form). Symbolism notwithstanding, it is the substance of this set which is intended to re-affirm Ayler’s lofty position within the hierarchy of all jazz and not just the historically grounded New Thing of the 1960s, by adding a bounty of musical riches—some previously only rumored to exist, others said to have been destroyed—to the available, albeit small, canon. Yet though this “new” material helps to clarify some of the speculation and misinformation about Ayler and specifically the evolution of his music, it also raises questions that perpetuate the mythology surrounding him.

The paucity of authorized Ayler recordings can be explained by several factors: from the point of his discharge from the Army in 1961, at age 25, he had less than a decade of life left; he spent significant time in Europe and Scandinavia, where his earliest recordings were made for labels with limited visibility, resources, and distribution; American record companies were wary of the seemingly chaotic sounds issuing from the Black avant-garde (and Ayler was the most extreme of all) until they brainstormed ways to market them as part of the “hip” counter-cultural revolution and/or manipulate and dilute the music and its extramusical significance with conservative, accessible productions; and Ayler himself was young, idealistic, and inexperienced regarding the business of music. His “official” recording career can be divided into three parts—the Scandinavian LPs, originally for Bird Notes and Debut (not to be confused with Charles Mingus’ ’50s label of the same name), which were reissued in the U.S. on GNP Crescendo and Arista/Freedom; the ESP LPs; and the Impulse LPs. None of these are included in the Revenant box. Some of what we are given here may have already been passed around among hardcore collectors in multi-generational dubs of questionable sound quality, other selections may be receiving their initial release. I confess that I’ve never been an Ayler “completist,” so I’ve not encountered any of this material before. Revenant has apparently invested in refurbishing of the source tapes where possible, so the sound varies from quite good (considering its origins) to disappointingly poor. More on that later.

While bemoaning the fact that there are no performances here of Ayler alongside John Coltrane or jamming with Ornette Coleman (though tapes of both are said to exist), collectors will not doubt covet most his collaboration with Cecil Taylor. Ayler first met Taylor in 1962 as the latter’s trio, with alto saxophonist Jimmy Lyons and drummer Sunny Murray, was playing in Stockholm. He felt the pianist was a kindred spirit, asked to sit in with them, and was forthwith added to the group—at least for a television appearance in Copenhagen on 16 November (a week before the trio, sans Ayler, played and was recorded at the city’s Café Montmartre). This surviving soundtrack (the visual portion apparently has been lost) is all that has so far come to light of their time together, though Ayler continued to appear intermittently with the Taylor band back in the States during 1963 and possibly early ’64. In his session-by-session commentary (part of the 208-page hardcover book included in the box), project supervisor Ben Young opts that “...this 23-minute performance is the first recording from anywhere in the jazz spectrum of a long-form improvisation with no overt synchronization—of time, structural harmony, or song.” While the strict definition of synchronized harmony, according to accepted Western theory, may not be broad enough to include the relatively key-free playing that Lyons and Taylor engage in, both here and in the Café Montmartre performances, let me suggest that their practice of flexible linear counterpoint—a few steps beyond the improvised-by-ear, harmonically complementary contrapuntal lines of the Lennie Tristano sextet’s 1949 “Intuition”—assumes a moment-to-moment attention to opportunities for related (however briefly it occurs) and unrelated interaction, and those places where their alignment seems least “synchronized” now may be heard as a simultaneous overlapping of no longer “dissonant” but, rather, extended harmonies. The new lesson this music, like Ives and Cage, teaches us is to hear harmony in a fresh way.

Ayler’s contribution, meanwhile, is not along the lines that Lyons and Taylor have worked out between them. He is, in a sense, playing even freer, with less attention to melodic/harmonic interaction with Taylor, and is instead using the piano and Murray’s drums as a rhythmic trampoline upon which he can bounce deep honks and contrasting figures of sound. Alternating between high and low registers, he stretches and elaborates motifs (was that a hint of “Cocktails for Two” flashing by?), sustaining a level of energy as his solo’s sole unifying force. His second solo has a grinding, growling, abstracted r&b intensity, reminding us of his pre-Army experiences touring with blues harmonica wizard Little Walter. This is brilliant music from start to finish, the equal of anything Taylor had recorded up to this time and, if not the first indication of Ayler’s mature path leading to the great ESPs of 1964, his first opportunity to interact with musicians comfortable with and fluent in his expanding vocabulary of freedom.

To put this performance into a fuller context, we must take a step back in time. Prior to the release of the Revenant box, the earliest Ayler recording to receive wide circulation was that of the seven performances of standards (plus one free piece entitled “Free”) from 25 October 1962, including “I’ll Remember April,” “Tune Up,” and “Moanin’,” issued initially in two volumes by Bird Notes. These show Ayler using dissonant and/or tonally distorted variants of pitch with phrasing that so deconstructed the familiar song form he befuddled the pickup rhythm section for the date, bassist Tobjörn Hultcranz and drummer Sune Spängberg. (Ayler was apparently dissatisfied with the results too, which often sound like a wayward rehearsal and led some critics at the time to complain that Ayler could not play his instrument properly.) Now, however, a three-tune session form 19 June 1962 with Ayler accompanied by a straightahead Finnish quartet led by guitarist Herbert Katz (who adds his own attractive, if mainstream, solos) reveals a fuller measure of the saxophonist’s abilities—and, by extension, the concept he was attempting—at the time. Here, Ayler maintains a hard tenor sound, perhaps approximating that of Sonny Rollins, without the extreme tonal distortions to be heard in the Bird Notes session of four months hence. On Rollins’ “Sonnymoon for Two,” his lines are constructed around a chromaticism that stretches the harmony but does not ignore it, and his phrasing does not break with the tune, as he would attempt to do in October. His sense of pitch and timbre is even less exaggerated on “Summertime” (which would reappear, of course, as a Picasso-like masterpiece of expressionist abstraction on the 1963 My Name Is Albert Ayler session), and he deftly alters dynamics to good effect. Finally, on “Green Dolphin Street” he begins with leaping phrases and tart but not inexact pitches sounding briefly but uncannily like Eric Dolphy, then builds to freer phrases that fit within the bar lines or cut across them without losing their implicit feel, eventually smearing notes, squawking, bending pitches, and squeezing scales into glisses. The hint of Dolphy is an intriguing one here, and suggests that though Ayler could have followed his example as a fruitful direction for harmonic exploration of conventional material, he rejected it in favor of the extreme sound-oriented techniques which would be put to even more stark, concrete use once he stopped trying to abstract standard material. Though the extreme techniques he was employing, strange and uncomfortable to many, caused Ayler to be branded a “primitive” by conservative critics, the evidence of this earlier step in a still-evolving process makes it ever more apparent that Ayler was in search of an original design, and though not his ultimate direction, this stage of his development would prove influential to subsequent explorers like Anthony Braxton, who was likewise inspired to re-orient himself to tunes “in the tradition.”

All of this is strong evidence that, as verbal reports from friends in Cleveland attest, Ayler could play standard material with perfect competence if he chose to do so. As if this is not proof enough, Revenant also provides us with a bonus, unannounced seven-minute CD containing two of Ayler’s 1960 (!) rehearsal performances with the 76th AG Army Band. These are now the earliest Ayler extant, on which he plays lead tenor, hewing closely to the melody of “Tenderly,” and playing rudimentary four-bar fills in a stiff big band rendition of Les Brown’s theme song, “Leap Frog.” The quality of Ayler’s playing here is that of a promising amateur, and he obviously woodshedded a great deal between 1960 and ’62, where we pick up the trail; nevertheless, these surprising examples, plus the assumption that Little Walter and bandleaders around Cleveland would not suffer a musical illiterate, refute the complaints that Ayler could not play in a mainstream fashion or with legitimate technique, and illuminate the lengths to which he went to develop an original style.

That style can be sampled in full bloom on the previously unreleased takes from the June 1964 Cellar Café gig that provided the material for the ESP album Prophecy. Most impressive, perhaps, is Ayler’s sound. Descriptions of his huge, room-filling tenor saxophone tone are approximated here by a big sound that resonates from the bottom, where he lingers, to the top register. He is no longer using familiar material, but his own simple themes which, though jettisoned over the course of the performance, initiate the emotional environment as Ayler spontaneously shapes his gestures into the true form of the piece. Though he is working within a new system of improvisational design, there are still momentary surprises retained from his more conventional playing—a brief blues inflection in “Saints,” and even the slight inference of a casual swing phrase in the theme statement of “Ghosts” before an episode of low-end vehemence. For many critics and listeners, this is the finest period of Ayler’s career, reaping the freshness of his new discoveries, unhindered by formal constraints, and assisted by an equally formidable rhythm section (bassist Gary Peacock and Sunny Murray) that enhanced the uniqueness of Ayler’s methods, rather than distracting from them.

A Copenhagen club date three months later gives us six Ayler originals, this time with Don Cherry’s added presence. (These performances were part of a 2002 single-CD release, The Copenhagen Sessions, on the Swedish Ayler label.) If anything, Ayler’s playing is reaching for more extremes, lifting into the upper register more often for punctuational screeches and sustained microtonal wails. Notwithstanding the off-hand casualness of Ayler’s introduction, “The next tune is called ‘Vibrations’, these “tunes” ignore song form and reveal the saxophonist shaping sound more concretely, occasionally repeating sing-song fragments in ironic paraphrase of orthodox melody, exuding a belief in sound as sanctified transformation. As with some martyred saints of the Catholic church, it’s hard to distinguish between pain and ecstasy in Ayler’s yearning howl, though his tenor saxophone soliloquy in “Mothers” (related to “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child”) has the directness of a preacher elevating his sermon into impassioned vocalization. Cherry’s cornet is an engaging counterbalance—relying on his experiences with Ornette, he does interact with the tenor saxophone in moments of mutual improvisation—and his lyricism is shadowed closely by Peacock’s bass. The lack of songlike artifice in these and the Cellar Café pieces gives rise to the notion that though some listeners may have felt that Ayler’s music was too complex to be accessible, his concept was that by rejecting song structure he was simplifying the music, making it more direct and winnowing it down to its essence, pure sound-feeling, that should ideally communicate more easily to everyone.

The next stage of Ayler’s evolution represented here is his 1966 quintet, beginning with two full CDs-worth of a live Cleveland concert (from a club called La Cave...is there a pattern here?) that found brother Donald Ayler taking over the trumpet role, the boisterous Ronald Shannon Jackson on drums, and marked one of violinist Michel Samson’s first appearances with the band. The material had changed once more, too, now featuring more of the short, catchy melodies that Ayler hoped listeners would go out of the concert humming to themselves—a march (“Spirits Rejoice”), an open, flowing aria shared between violin glisses, double-stops, and trills and the tenor saxophone’s hoarse, yet restrained expressionism (“untitled minor waltz”), and Donald’s melodramatic “Our Prayer.” But, rather than sounding hermetic, the simple themes have been inflated to anthem-like proportions through emphasis and repetition; the music is more theatrical with arrangements—shorter solos, repeated motifs (“Our Prayer” imbued with a “Three Blind Mice” motif—how much simpler can music get?), more varied with instrumental colors and ensemble textures. The rousing solos are more compact though no less intense—Donald’s trumpet blaring, sputtering, and raising pitch-by-pitch from sheer urgency with almost no range or contour, like a man at a punching bag, and guest tenor saxophonist “Reverend” Frank Wright following Albert’s example by chewing and spraying fractured notes. Though the music’s coarse, propulsive ensembles, tumbling rhythms, and high-energy sound projection may alienate as many listeners as it seduces, the presentation seems closer to the extreme, if egoless, drama found in the Holiness church as well as the roughest of rural roadhouses, calling to mind Ayler’s desire (as told to Nat Hentoff) to play “...folk melodies that all people would understand.”

The band sounded better, and is captured in better sound, at the concerts in Berlin and Rotterdam during the same November 1966 tour of Europe that has produced recordings from Lörrach, Germany and Paris. As opposed to the Cleveland tapes, Bill Folwell’s bass is now audible, and Samson is more comfortable within the ensemble, his violin amplified properly so that his important contribution is equal to the others, coloring the music, droning, soloing with greater nuance, and caressing the horn lines. At the Rotterdam concert, beaver Harris, the new drummer, attacked the drums with a violence unimaginable during Sunny Murray’s reign, reconfiguring the group dynamic in keeping with the more dramatic ambiance of the full ensemble. But the band’s heaven-storming potential seems to have reached fruition seven months later at, of all places, a Newport Jazz Festival appearance. With Milford Graves behind the drumset, there is a palpable boost of energy that inspires a looser, freer exchange of individual components—Samson flies over his fingerboard with a wider-than-usual range of details, Ayler vocalizes with abandon, brother Donald’s trumpet blasts puncture the ensembles, and the sounds blister the air. Again, the horns’ exaggerated vibrato and the barrage of drums reinforce the oft-quoted parallels to the raw, immediate, folk and spiritual-inspired origins of New Orleans brass band music.

Consensus has it that Ayler’s career was in decline from the time he signed with Impulse Records. Most of Love Cry, the first release on the label, was recorded at the end of August 1967, and consisted of abbreviated versions of classic themes like “Ghosts” and “Bells.” But John Coltrane had died earlier that summer—remarkably, Revenant includes a six- minute segment (or was this the complete performance?) of Ayler’s band performing at Coltrane’s funeral, a regrettably muffled but nonetheless moving plaint with Ayler’s cries of loss most audible—and much of the New Music scene was wondering how to proceed. Ayler’s band appeared less and less frequently, and he sat in with other groups on occasion. There are tapes here of his guest appearances with Pharoah Sanders in January 1968, where Sanders alternates between outside blowing and articulating melodies from his own Impulse album Tauhid and Ayler attacks like a shark, and on alto alongside saxophonist Sam Rivers in brother Donald’s group from January 1969, though the sound quality is so congested that it’s difficult to distinguish details within the squall other than trumpet flourishes and cymbal splashes.

Ayler’s second release on Impulse, New Grass, was considered by many to be a commercial sell-out, an over-produced attempt to market Ayler to the young, rock audience by layering free saxophone and “Love Generation” platitudes atop a pop/r&b groove. Impulse producer Bob Thiele was blamed for the debacle, but there is an interesting review of the album by Black writer Larry Neal that condemns not the concept, but the way it was handled. Neal cites that the vocals are weak and the rhythms merely bland (i.e.: white) approximations of authentic r&b. Was Ayler a pawn in Thiele’s game? The answer may not be as obvious as it seems. For one thing, remember that Ayler had fond memories of his time playing with bluesman Little Walter and the popular r&b bands around Cleveland during his apprenticeship. It has also been pointed out often that Ayler’s extreme techniques—from guttural honking to overtone screeching—are an extension of the r&b tradition of exaggerated sax gestures, a style of playing which was hugely popular during the 1950s, and Ayler was no doubt a fan of players like Big Jay McNeely, Earl Bostic, and Arnett Cobb. Then there’s the hurdle of Ayler’s spirituality. There are those who would canonize Ayler as a pure, innocent agent of transcendence and a Higher Calling, and which finds the sacred and secular incompatible. Yet there is a strong (and thoroughly analyzed and documented) connection between Black church music and the blues. Further, though Ayler displays his deep spirituality both in a short interview excerpt from 1966 (on one of the two CDs of interviews included here) and in a reprint of his apocalyptic essay published in a 1969 issue of The Cricket (edited by Amiri Baraka, Larry Neal, and A. B. Spellman), in over 90 minutes of interviews from July 1970—four months before his death—Ayler comes across as gleeful, gabby, and anything but a spiritual mystic. Nor is there any trace of the depression that was attributed to him in his final days, no dark thoughts, no paranoia. There is almost no mention of spirituality, God, or the Bible; instead, laughing frequently, he talks about wanting to play Bach on the saxophone, equates Ornette and Charles Ives, and says he loves Horace Silver. Even more to the point, he doesn’t complain about Impulse or Bob Thiele wanting him to record more commercial music—he is happy about the money he was paid, in fact brags a bit, and is concerned about his future earning potential, looking for festival gigs, and upset that Sinatra and Tom Jones might be stealing his ideas for songs (okay, perhaps there was a bit of paranoia in his thinking).

The point is that, although it may have been Thiele’s idea (or that of some bean counter at the record company) to begin with, Ayler was certainly willing, possibly anxious, to record in a “simpler,” more popular style in order to reach a larger audience. At first, he wanted to do it on his own terms; he played two weeks of preparatory gigs at a rock club, the Café au GoGo (apparently not recorded, alas) and brought pianist Call Cobbs, regular bassist Bill Folwell, and studio r&b drummer Bernard “Pretty” Purdie (probably at Thiele’s request, since he was not the drummer at the rock club gig) in to lay down demo tracks for the album. The four tracks we have at hand were rejected by Thiele, who brought Ayler back into the studio to re-record with a group supplemented by a batch of studio pros. These demos are curiosities, rehearsal takes with unfinished arrangements and minimal rhythm section involvement, of banal songs Ayler co-composed with Mary (Maria) Parks. Though wanting to sound like a suave soul singer, Ayler stumbles through the lyrics of “New Grass,” and what’s interesting about “Thank God for Women” is not the message, but the music—an endlessly repeated theme that sounds like a paraphrase of Monk’s “Friday the 13th” over a boogaloo beat. On an untitled blues, however, Ayler’s tenor saxophone howls in a manner eerily close to his 1962 style of playing, as if nothing has been lost and he could return to any point of his career at any time.

The final music here, four previously unissued small club quartet performances (no Mary Parks) recorded during the time Ayler appeared at the Foundation Maeght, St. Paul-de-Vence in France (first released on Shandar), four months before his death, finds Ayler playing extended solos once again, ornamenting the melodies of “Mothers” and “Children” along arpeggiated, sometimes modal contours. More interestingly, on three untitled pieces Ayler seems to be reverting back to an earlier (circa ’64) approach, on one subverting Call Cobbs’ romantic, harmonically conservative piano with intense upper-register overtones, and imposing an aharmonic improvisation onto a Sephardic-sounding melody on another. (The original cassette tapes have deteriorated or been sloppily edited, but the music is listenable.) Ben Young, supported by a quote from bassist Steve Tintweiss, feels that Ayler didn’t want to exhibit his newer pieces for fear of being bootlegged and losing royalties and so offered a free-blowing jam, yet it’s ironic that the last music we have from Ayler is neither visionary nor compromised, but the flamboyant, exhilarating, intently personal manner of improvising he made his mark with, and is now established as a continuing force in creative music.

There are conflicting accounts of Ayler’s final days. Some acquaintances felt he was relatively optimistic about the future (as he sounds on the July 1970 interview tape), others say he was deeply depressed and suicidal. Rumors about his death range from the accidental to the possibility of a mob hit. It’s impossible to speculate on what the future of his music might have been had he lived—perhaps a more successful “back to the roots” concept (imagine Ayler squealing alongside Maceo Parker backed by the James Brown band, or riding Sly and Robbie’s riddim, or mixed up with George Clinton’s menagerie) or maintaining his Free Jazz innovator status (at 68, he could be soloing next to Peter Brötzmann right now). Legends require not only a comet-like impact, but also a large amount of ambiguity and mystery. We still may not know all of the answers, but at least we have more of the story than ever before.

Albert Ayler: Holy Ghost is available from

Revenant

P.O. Box 162766

Austin, TX 78716

www.revenantrecords.com

*

The San Jose Mercury News (5 December, 2004) - USA

A startling rediscovery of a jazz original

ALBERT AYLER'S MUSIC DELIVERS JOLT ON 9-CD SET

By Richard Scheinin

One of the most exhaustively researched and lovingly produced jazz packages of recent years has just been issued by Revenant Records, a small independent label. The nine-disc set is called ``Albert Ayler: Holy Ghost.''

Coincidentally, ``Revenant'' means ``ghost'' or, according to Webster's, ``a person who returns, as after a long absence.'' The definition applies, eerily, to Ayler, a startling musician -- the Jimi Hendrix of jazz -- whose brief, mercurial career ended in 1970 when his body was fished out of New York's East River. ``Holy Ghost'' documents the musical evolution of the saxophonist and free-jazz icon, drawing on radio and television sessions, live concert and demo tapes and private recordings, most previously unissued or sporadically bootlegged.

Ayler (pronounced EYE-ler) was 34 when he died. No one knows what happened to him, whether his death was an accident, suicide or, as rumored, the result of foul play. His unresolved, mysterious death fit the arc of his life: Ayler played mysterious music.

Still, it carried his audiences into a world of delirious joy. For listeners hungry for something new, for music with a jolt, Ayler, 34 years dead, could be the medicine they need. I assure you, there is nothing like it. His music has as much impact as rap, punk or metal, and it is soulful, phenomenally so. It is a music of essences, rooted in the black church, blues and the broadly smeared expression of earlier jazz masters, including Sidney Bechet.

Influenced Coltrane

Largely forgotten, Ayler was profoundly influential during his short life: One of his greatest fans was the saxophonist John Coltrane, whose late-period explorations were influenced sharply by the younger player. Many of today's saxophonists, aping late Coltrane, don't even realize how closely they really are aping Ayler.

He wrote ringing, anthemic melodies with such titles as ``Truth Is Marching In,'' ``Spirits Rejoice'' and ``Ghost.'' These songs have an ancient, timeless feeling about them; on first hearing, there is a sense of already knowing the melodies, which draw on spirituals, parade marches and folk tunes.

Ayler would play these songs with a massive sound that often incorporated a swooning, almost drunken vibrato. Then his band would break into a collective roar -- a giant hosanna, waves breaking over waves, with Ayler blasting, moaning, glissing and gurgling on tenor, throwing out thick brush strokes of sound, coming at you on a bed of continuously spreading rhythms.

Like Coltrane, Ayler was a quester, a spiritual striver whose music can be heard as a march toward God, at a time when jazz was becoming a subversive, mystically inclined ``energy music.'' A religious man who grew up playing his horn in a Cleveland church with his musician father, Ayler spoke often about music as universal energy, an expression of the Holy Spirit.

Picking up on this theme, Revenant has housed the nine discs of ``Holy Ghost'' in a ``spirit box,'' molded from plastic to resemble a hand-carved funerary box of onyx. It holds a 208-page book with essays by Amiri Baraka, Val Wilmer, Ben Young and other free jazz chroniclers; career and recording chronologies; testimonials from artists who knew and played with Ayler; photos, memorabilia, even pressed forget-me-nots in a wax envelope.

The final two discs are of two hours of interviews with Ayler. In 1964, he is gentle and affable. In 1966, he is in a dark mood, consumed with the book of Revelation, warning, ``It's getting late now.'' In 1970, he defines improvisation as the ``expression of one's feeling through suffering pain.''

The package from Revenant -- a label founded by the late guitarist John Fahey, another iconoclast -- is over the top. But so was Ayler's music. He liked to say that his music wasn't about notes; it was about sounds and feelings -- and, oh man, did he have feelings. Certainly there were musicians and listeners, many of them, who cringed at Ayler's unhinged sounds, thought him unschooled, a primitive, a lunatic, a faker.

For some, Ayler's music still grates. I have always found it to be embracing and a challenge, matching melody with chaos, expressing a fierce beauty. Ayler's was a heart of peace inside a battle cry. Listening to him is like having your subconscious unpeeled, so that you enter a secret, roiling expanse of rage, desire, then intense calm. It's simultaneously soothing and unnerving to go there. His ``Sixties'' music continues to define our times.

In the beginning

The earliest recordings on ``Holy Ghost'' are 15 minutes of Ayler playing standards with a U.S. Army band in 1960 when he was stationed in France. But the set really starts with Ayler two years later, at 25, performing on a Helsinki radio show with a local, straight-ahead rhythm section. He plays ``Summertime'' and ``On Green Dolphin Street,'' bridging bebop and free jazz, sometimes sticking to the chord changes, sometimes riffing modally, sometimes veering toward the swoops and wide vibrato that would become his calling cards. Always, there is blues feeling; Ayler toured with Little Walter at 17 and referred to his music as ``the real blues . . . the new blues.''

Later that same year, in a Copenhagen television recording session by pianist Cecil Taylor's band, Ayler steps up to the microphone with braying low notes, squeals, flutterings -- the blues gone mad. This 23-minute segment already has been labeled the ``missing link'' in the documentation of long-form improvisation in free jazz. The music was no longer about chord changes, cyclic harmony and all that. It was about texture, vibration, new systems of organization and rarefied intuition.

But I prefer what unfolds beginning in 1964, in sessions by Ayler's own trio at a Manhattan club called the Cellar Cafe. Now we hear that sense of overwhelming spirituality, transmuted through Ayler's unforgettable melodies, the prickly, prodding bass of Gary Peacock (better known in recent years as Keith Jarrett's band mate) and the saturating drums of Sonny Murray.

When trumpeter Don Cherry joins the group in Copenhagen, there is absolute liftoff. Tangling with Cherry, Ayler's horn is yelping, bellowing, trilling across wide intervals: Coltrane sounds very much like this, three years later, on a famous live recording of a tune called ``Leo.''

If you can handle the varying sound fidelity on ``Holy Ghost,'' which ranges from poor to acceptable, there are all sorts of highlights as the music moves forward. Ayler plays with future Coltrane drummer Rashied Ali, who has a heavier attack than Murray. And in 1966, Ayler forms a quintet with his trumpet-playing brother Donald; their connection is symbiotic.

The first gig -- you get to hear it -- happens at La Cave, a club in Cleveland. Dutch concert violinist Michel Samson, a walk-on who became an Ayler regular for the next year or two, dives straight in, identifies tonal centers, double-stopping, sliding and underscoring the tunes, which now become bold declarations. Donald proclaims them, over and over, as Albert decorates his songs with Pentecostal filigree.

The music becomes tight, stripped down, as the brothers riff, and the rhythms grow more straightforward. Rhythm was important to Ayler: ``All music must have the roots, like of Louis Armstrong -- must have rhythmic truth,'' he once said. Here, drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson pushes with rockish rhythms, or New Orleans-like rhythms, while the front-line instruments -- violin, trumpet and tenor -- fly up to commune at ever higher frequencies.

If you could get inside a swarm of butterflies and hear the massed sound of the thousands of beating wings, it might sound like this. Ayler might have likened the sound to the beatings of angel wings.

It's often said that the jazz avant-garde killed the jazz audience, because the music grew too intellectual. But this music is blood and guts. If jazz traditionally has been about tension and release, Ayler's music is largely about release. It's cathartic.

Jazz history

At the 1967 Newport Jazz Festival, the band came on after the Modern Jazz Quartet -- in the rain, like Hendrix at Woodstock. Ayler's best drummer, Milford Graves, was on hand and the music practically levitated; you hear it, feel it, on these recordings. You also get to hear Ayler, brother Donald, Graves and bassist Richard Davis performing at Coltrane's funeral in New York in 1967.

There are disappointments: a long, unfocused concert segment with Pharoah Sanders at Harlem's Renaissance Ballroom in 1968; embarrassing demos for Ayler's goofily misguided R&B album, ``New Grass,'' on the Impulse label, also in 1968; a Town Hall concert from 1969, with Donald Ayler as leader, that sounds like a distant field recording and is only of historical interest.

But ``Holy Ghost,'' overwhelmingly, pulls history back into focus. It sets Ayler back on his pedestal, alongside Coltrane, Taylor, Ornette Coleman, Sun Ra and other revolutionary jazz figures. The music speaks eloquently, though Ayler, in the two discs of interviews, never quite articulates what his music was about. For long stretches, somewhat obsessively, without fielding a single question, he plows through the story of his life, sounding agitated, anxious to cram it all in.

He comes across as a good soul, but, toward the end of his life, something had tipped. He wants to be upbeat but can't help sounding rueful: ``I never go where I should be going,'' he says at one point. Life didn't work out for Ayler, but he left us his music, a holy gift.

`Albert Ayler: Holy Ghost'

Nine discs of rare and previously unissued recordings

Label: Revenant Records

Price: About $95 at most outlets

*

The Portland Phoenix (16 December, 2004) - USA

A tale of two saints

Albert Ayler and Lenny Bruce get boxed

BY JON GARELICK

Saint is a tough gig. But when you’re an artist who dies young and misunderstood — unappreciated, broke — that can be your posthumous luck, good or bad. What you represent tends to overshadow what you did. Such is the stuff legends are made of.

The jazz-saxophonist Albert Ayler was born in Cleveland in 1936; his body was found floating in New York’s East River in November 1970. The comedian Lenny Bruce was born Leonard Alfred Schneider on Long Island in 1925 and died of a morphine overdose in Los Angeles in August 1966. Both men were influential, trailblazers, visionaries. And they knew it. Long before Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, Ayler spoke about "the message" his music delivered. The message wasn’t about social transformation; it was musical and spiritual. A new nine-CD box set from Revenant, Albert Ayler: Holy Ghost, draws its title from a statement attributed to Ayler: "Trane was the father. Pharoah was the son. I was the holy ghost." Lenny — represented by the new Shout! Factory six-CD compilation Lenny Bruce: Let the Buyer Beware — is quoted in the box’s booklet: "I’m not a comedian. I’m Lenny Bruce."

Although he was younger than the practitioners of the first wave of "free" jazz — Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, and Cecil Taylor — Ayler was equally influential. It’s difficult to imagine Coltrane’s form-busting late work — from Ascension on — without Ayler. When you hear tenor-saxophonists "overblowing" in extended passages of altissimo, that’s usually Ayler coming to you via Coltrane — the holy ghost, as it were, through the father. Ayler favored New Orleans–style marches and folk-song forms, hymns, simple melodic structures as opposed to beboppish complex harmonic patterns. There’s some debate in the 208-page hardcover book included with Holy Ghost as to whether Ayler could play chord changes. The bassist Gary Peacock, who played on some of Ayler’s best recordings, says he just didn’t care about them.

What Ayler did care about was energy, "vibrations," spirit. His upper-register workouts were endurance tests — physical as much as musical, for player and audience. The musicians quoted in Holy Ghost talk about his stamina, his volume, his shredding vibrato, his preference for hard plastic reeds as opposed to cane, metal mouthpieces rather than plastic, all meant to enhance projection rather than abet nuanced articulation.

Plenty of performances included in Holy Ghost give a good idea of the physical presence of Ayler’s sound. On a live recording from 1968 (from disc five), Ayler is playing with Pharoah Sanders’s band — a medley of Sanders’s hard-boppish blues "Venus" with the more spacious, modal "Upper and Lower Egypt." Sanders’s tonal warmth and scale-based patterns make his themes and solos immediately accessible to a post-Coltrane audience, even when he breaks into Ayler-like vibrato-laden split tones and shrieks. Ghost book annotator Ben Young gives a good play-by-play analysis here, sorting out Sanders from Ayler as well as an unidentified alto player and a third, unidentified tenor. Ayler’s solo begins at around the 13-minute mark. Working the vampish "Egypt" theme, he projects in a high, hard, whistle-like altissimo and sustains it. Young rightly calls this a "parody" of the theme. Sanders’s "out" excursions are raspy, throaty, wind-driven. Ayler’s are unbroken streams that seem to pour directly from his solar plexis. What’s more, as Young points out, Sanders’s upper-register exclamations serve as orgasmic, extended climaxes to solo statements; for Ayler, those passages, like "Egypt," were the solo statements, sometimes fully fashioned melodies, delivered with peerless control. Other saxophonists might go into the stratosphere for expressionist effects, but Ayler lived up there.

Despite its opulence, the Ghost box is not a starters’ kit. For the sake of their pocketbooks, if nothing else, Ayler novices are recommended to search out his individual recordings on ESP-Disk, especially Spiritual Unity, with bassist Gary Peacock and drummer Sunny Murray. ("I remember when I was in Paris, I listened to that daily. Daily," emphasizes Steve Lacy in the notes.) There’s also the beautiful double-disc set from Impulse Live in Greenwich Village, which benefits from superior recording quality and an almost chamber-jazz decorum, especially in the use of strings (cellist Joel Freedman and violinist Michel Samson).

What’s on Ghost for the Ayler fan in addition to seven discs of rarities, alternate takes, and previously unreleased material is two discs of interview material, on which he sounds sweet, manic, melancholy, and painfully sincere. Some material, such as his fabled performance at John Coltrane’s funeral, or a wild and woolly performance with his brother Donald’s band, is of more historical than musical interest. But a 23-minute performance with Cecil Taylor’s band (with Peacock, Murray, and alto-saxophonist Jimmy Lyons) is a revelation; Ayler’s gestural rhythmic patterns are the perfect complement to Lyons’s Bird-like classicism and of a piece with Taylor’s overall conception. Young calls this "the first recording from anywhere in the jazz spectrum of a long-form improvisation with no overt synchronization — of time, structural harmony, or song" — the beginning, in other words, of free jazz. There’s some beautiful work with Cherry (Ayler’s preferred trumpeter before bringing in his brother Donald), and more with the Ayler/Peacock/Murray trio, in which one hears that Ayler was as sensitive to ensemble delicacy — the weblike cymbal work of Murray, the touch and tone of Peacock’s melodic embellishments — as to sonic juggernauts. The box also includes facsimiles of family photos, a chapbook by poet Paul Haines, a handbill from the New York jazz bar Slug’s, and an envelope of dried, pressed flowers — Albert’s earthly relics.

WHEREAS AYLER DURING HIS LIFETIME was known among jazz fans, Lenny Bruce by the time he died had become a minor international celebrity. His big break came when he tied for first place in an Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts radio-show competition in 1948. (The performance is included on the Shout! set). By the end of his career, he’d appeared on Steve Allen’s Tonight Show, sold out Carnegie Hall, made headlines for obscenity busts, and been refused admittance to Great Britain as an "undesirable alien." It’s difficult to disagree with the contentions of most of his hagiographers that Lenny was hounded to death by the cops. It didn’t help that — in his mania — Lenny’s performances devolved into legal briefs and the reading of court transcripts. Posthumously, Lenny has become the poster boy for artistic free speech, and there’s virtually no comedian since Richard Pryor who hasn’t thanked him for paving the way.

What Lenny Bruce: Let the Buyer Beware reminds us is that Lenny Bruce was actually funny — much funnier than the kind of bits that got him busted or gained him notoriety. Some of these pieces now survive (on Let the Buyer Beware and his Fantasy recordings) as historical documents — early performance art. "Are There Any Niggers Here Tonight?" and "How To Relax Your Colored Friends at Parties" pre-date Pryor, Eddie Murphy, Quentin Tarantino, and Randall Kennedy by a couple of decades, but some 40 years later, these pieces are little more than toothless preaching. Equally flat are pieces like "Religions, Inc." and "Christ and Moses," in which Lenny "exposes" the hypocrisy of religious crusaders and moralists.

What’s still fresh and funny on Buyer Beware is Lenny’s Jewish hipster flow, the spritz of his spiels, and the intimacy of his delivery. It’s difficult to think of any current stand-up comic who possesses his willingness to break form and engage in back-and-forth banter with an audience, who’d risk departing from the set-up-and-delivery of laughs for spontaneous free-association. To judge from the pieces here, most of which hadn’t been released before, that’s where the "danger" came from in Lenny’s performances — never being able to predict what he’d do or say next. He jumps on a pompous audience member for smoking a cigar ("What the fuck is it? Why is it that you live up to the image, man?") and goes off on a riff about Johnny Mathis getting hassled by a redneck in a Las Vegas bar for supposedly "offending" a white waitress.

Lenny was the first hipster comic. In an era of nervous schlemiels like Bob Newhart and Shelley Berman, a brainiac like Mort Sahl, or even his friend Jonathan Winters, Lenny’s finger-snapping punctuations along with the rhetorical flourish of his constant "Dig!" and Yiddish interjections ("emmis!") set him apart. He sees the world in terms of his Jewish childhood (his Aunt Mema is a constant reference) and show business. His take on the typical Warner Bros. prison movie, "Father Flotsky’s Triumph," encompasses his feelings about race, sexuality, and, of course, authority. His one side-splitting bit here is the classic "The Palladium," in which a mediocre comedian gets his wish to play a "class" room, London’s Palladium Theatre — and bombs.

Of course, it’s still shocking to hear Lenny casually and "appropriately" use the word "cocksucker" and realize, "This is what got him busted?" Or to hear him challenge the "lie" that Jackie Kennedy was "going for help" as she climbed over the back of the limo. Buyer Beware producer Hal Willner points out that Mel Gibson makes comedy like Lenny’s more pertinent than ever. Jon Stewart, Lewis Black, and the rest of the crew on The Daily Show can take care of The Passion of the Christ just fine, thank you, but compared with Lenny Bruce, they really are just nice Jewish boys.

*

SF Weekly (22 December, 2004) - USA

Albert Ayler

Holy Ghost: Rare & Unissued Recordings (1962-70) 10-CD Spirit Box

By Sam Prestianni

Holy Ghost is an extraordinary career-spanning box set of rarely heard material by revolutionary saxophonist Albert Ayler. But it may not be a must-have for even the most serious jazz collector. While the archival aspect of the package is noteworthy -- eight CDs of live performances, an assortment of historical ephemera (including two discs of interviews), and a 200-page book filled with biography, criticism, and anecdotes -- nearly half of the performances are literally unlistenable. Here's why: Though Ayler drew his melodies from tuneful African-American spirituals, old-time folk music, and New Orleans marches and dirges, his concept was largely about channeling freedom and life energy -- "Not about the notes," as he often said. Thus, on trademark tracks like "Spirits Rejoice" and "Truth Is Marching In," Ayler directs his quintet toward a kind of speaking-in-tongues fervor, the strength of which is both astonishing and hair-raising. But combined with the bootleg quality of many of the recordings, it's too often nearly impossible to hear. Sure, the listener can feel an unbridled power brewing beneath the noise -- and there are huge moments when Ayler's singular presence soars front and center -- but noise is the dominant trait here, and the gut response: Turn it off.

*

[Remco Takken is freelance muziekjournalist en radiomaker bij De ConcertZender - 2005] - Netherlands

Albert Ayler: Holy Ghost

By Remco Takken

Het zat heel eenvoudig inelkaar, in de saxofonistenwereld van de jaren zestig. John Coltrane was de Vader, Pharoah Sanders de Zoon, en Albert Ayler de Heilige Geest. Althans, zo zag Albert Ayler het zelf. Een nieuwe prestigieuze box met als titel ‘Holy Ghost’ laat horen hoe Ayler kwam tot deze gevleugelde woorden. Negen cd’s lang.

Het was 25 november 1970 toen Aylers dode lichaam werd gevonden in de New Yorkse East River. Hij werd slechts 34 jaar oud, zijn carrière als saxofonist besloeg slechts tien jaar. Tijdens dat korte leven had niet alleen de jazz een ander aangezicht gekregen, ook Ayler had inmiddels de nodige schepen achter zich verbrand. Van een hard studerende Sonny Rollins-epigoon werd hij free jazzblazer met een gospeltic. Van daaruit haalde hij de nietsvermoedende luisteraar iedere grond onder de voeten vandaan. Ritme, melodie en tijdsduur werden in het Albert Ayler Trio als een elastiekje aangespannen en weer losgelaten. Rond 1968 wilde Ayler de souljeugd naar zich toe trekken met een funky groep rond drummer Bernard Purdie en basgitarist Bill Folwell.

Verloren gewaande snippers

De onlangs uitgebrachte overzichtsdoos bevat vooral verloren gewaande snippers met historisch materiaal, veel (lange) interviews en meer. De stormachtige muziek tijdens de begrafenis van John Coltrane, een informeel en tot nu toe onuitgebracht concert in Frankrijk, een van de weinige opnames van Aylers geestelijk getroebleerde broer Donald, een concert in de Rotterdamse Doelen. Het is teveel om op te noemen.

Wat er niet op staat? In feite is volledig voorbijgegaan aan de reguliere platen, de albums die unaniem worden geroemd in alle jazz encyclopedieën. Naar ‘Spiritual Unity’, ‘Bells’, ‘Spirits Rejoice’, ‘Live In Greenwich Village’, of ‘Music Is The Healing force Of The Universe’ zal de geinteresseerde leek vergeefs zoeken. ‘Holy Ghost’ is de definitieve vervolmaking van Albert Aylers platenouevre. Alle composities die ook maar enigszins van belang zijn in Aylers relatief kleine oeuvre zijn aanwezig in onuitgebrachte live-versies.

Army Band

Ook de allereerste opnames die Ayler ooit maakte zijn te vinden in deze box. Deze nooitgehoorde eerste sessie uit het Amerikaanse leger dateert uit 1960, twee jaar eerder dan de opnames die al verschenen onder de titel ‘First Recordings’. Ayler was 24 jaar oud, hij stond op een kruispunt in zijn leven. De brave tenorsaxofonist van de 76th AG Army Band wilde uit het keurslijf stappen van Charlie Parkers akkoordendwang, maar vooralsnog speelt hij keurig mee op ‘Tenderly’ en ‘Leap Frog’. Hier kon toch niemand bezwaar tegen hebben, maar dat zou snel veranderen.

Saxofonist en jeugdvriend Lloyd Pearson herinnert zich Aylers terugkeer uit het leger, en bespeurde een enorme omslag in diens spel: “Ik zei: damn, the cat sure done got weird! Iedereen was bezig met akkoordenschema’s, en als je dat niet deed, dan vond men dat je niet kon spelen. Hij werd afgewezen door het publiek, door de muzikanten, door iedereen eigenlijk. Ze lachten om zijn stijl, omdat ze het nog nooit gehoord hadden.”

Domme mentaliteit

Om de in zijn ogen domme mentaliteit van de Amerikanen te ontlopen, vertrekt Ayler naar Scandinavië. Daar zou zijn vooruitstrevende muziek beter worden begrepen door het jazzminnende Europese publiek. Hij kan er goede opnames maken en verwante musici ontmoeten. De stormachtige groei die zijn spel in die tijd doormaakt is duidelijk te horen op de eerste cd in de ‘Holy Ghost’-box.

In het Finse Herbert Katz Quintet klinkt Ayler nog als een jonge hondenversie van Sonny Rollins: vrolijk, anarchistisch maar vooral swingend naast de vaardige gitarist-bandleider. De liedjes ‘Summertime’ en ‘On Green Dolphin Street’ zijn integer neergezet, duidelijk is dat de noord-europeanen zeer toegewijde bebop-adepten zijn.

Duikvlucht naar piepknor

Ayler maakt in de loop van 1962 een regelrechte duikvlucht van vrolijke clubjazz naar regelrechte ‘piepknor’, zoals vrije improvisatie destijds werd genoemd. Albert Ayler had de avontuurlijke trompettisten Bill Dixon en Don Ellis ontmoet, en is speciale gast bij het Cecil Taylor Quartet, een vrij improviserende avantgardegroep waarin Aylers latere drummer Sunny Murray meespeelt. Er is een goed klinkende opname van zo’n twintig minuten bewaard gebleven van een televisie-uitzending rond Cecil Taylors pianospel. Een mooie aanvulling op Aylers oeuvre als pionier van de free jazz.

Altsaxofonist Jimmy Lyons en drummer Sunny Murray vormen hier het hechte koppel waarvoor Cecil Taylor later een passend woord vond: ‘unit’.

Dronken rondzwalkende noten

De publieke doorbraak van Albert Ayler als bandleider, componist en saxofoonvernieuwer laat nog even op zich wachten. In juni 1964, een maand voor de historische monosessies van de elpee ‘Spiritual Unity’, maakt de Amerikaanse dichter Paul Haines een opname van een concert dat later ettelijke malen op plaat en cd zal verschijnen.

Dat een deel van dit materiaal nu opnieuw, en wederom in een iets andere configuratie in de ‘Holy Ghost’-box is uitgebracht, kan worden gezien als een zwaktebod. De rechten van de ‘Spiritual Unity’-sessie ligt bij het label ESP- Disk’, dat geen medewerking verleende aan de uitgave van de cd-doos. Samensteller Ben Young moet gedacht hebben dat het remasteren van een uitgemolken live-opname de meest galante manier was om tóch op een legale manier iets te kunnen uitbrengen van de belangrijkste periode uit Aylers leven.

Het ‘Cellar Café Concert’, ook bekend onder de titels ‘Prophecy’ en ‘Albert Smiles With Sunny’ is hoe dan ook mooi om naar te luisteren. Het zijn niet alleen de eerste opnames van een Albert Ayler die zichzelf eindelijk gevonden heeft. Het trio waarmee hij speelt is met een gerust hart ‘definitief’ te noemen: Gary Peacock is de bassist die zich op de gekste momenten losmaakt van thema, akkoorden en melodie, Sunny Murray is de vrije geest achter de drums.

In het bijgevoegde hardcover-boek ‘Holy Ghost’ is een interessante passage opgenomen over het vrijzwevende saxofoonspel van Ayler in 1964. Daarin wordt gesteld dat een klein aspect van Aylers muziek nog altijd open staat voor nader onderzoek. Bestaat de in het Cellar Caféconcert steeds terugkerende ‘dronken rondzwalkende noot’ niet eigenlijk uit een frase van verschillende tonen in één? Wat is het toch met dat gekmakend langzame vibrato? wordt het hier ingezet als een afgeraffelde triller? Alleen al als studiemateriaal van geflipt saxofoonspel, om te vergelijken met de emotionele uitbarstingen op het studio-album ‘Spiritual Unity’, bevat dit concert onschatbaar materiaal.

Financiële armslag

Na het plotselinge succes van deze muzikale wervelstorm is er in het najaar van 1964 genoeg financiële armslag om het trio uit te breiden met een in avantgardekringen vermaard trompettist. Don Cherry was bekend van zijn werk met Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane en Archie Shepp. In de jaren tachtig komt zijn naam op opvallende wijze terug in het nieuws: hij is de vader van zangeres Neneh Cherry.

Cherry doet mee tijdens een Europese tournee waarvan postuum het een en ander op plaat en cd verschijnt. De tweede cd uit de nieuwe Aylerbox bevat een Deens concert met Cherry dat eerder al verscheen onder de titel ‘The Copenhagen Tapes’. De opnames zijn zeer de moeite waard vanwege de korte, maar zeer intense momenten van gelijktijdig samenspel tussen Ayler en Cherry. De foto’s van dit duo in het bijgevoegde boek zijn afkomstig van Ton van Wageningen. Hij was aanwezig bij een vergelijkbare sessie in Nederland, waarvan opnames later uitkwamen onder de titel ‘The Hilversum Session’.

Zwart racisme

De vroegste vormen van ‘free jazz’, ‘free music’ of ‘the new thing’ hadden een duidelijke connectie met de zwarte burgerrechtenbeweging. Het was een uiting van de tijd, ook free jazz maakte deel uit van het vocabulair van de ‘protestgeneratie’ in de jaren zestig. Een bijverschijnsel van de ‘black power’-achtige denkbeelden van zwarte jazzmuzikanten was de weigering nog langer met blanken te spelen. In de Holy Ghost-box is een jam te horen met pianist Burton Greene, uit het midden van de jaren zestig. Niet veel later zou Greene, een blanke jood, het steeds verstikkender klimaat van de New Yorkse ‘vrije’ muziekscene ontvluchten. Tot op de dag van vandaag woont hij in Amsterdam.

Deze vorm van zwart racisme heeft een hoorbaar negatieve invloed op de muzikale kwaliteit van een van de sessies in de box. Op een nooit eerder verschenen plaatkant van het Pharoah Sanders Ensemble (met Ayler) speelt een nogal houterige drummer, Roger Blank. De originele slagwerker van deze groep, Bobby Kapp, was goed ingespeeld. Helaas had hij niet de gewenste donkere kleur om mee te mogen doen op een elpee voor het Jihad-label van de militante dichter Amiri Baraka.

In Cleveland, op 15 april 1966 om precies te zijn, mocht de Nederlandse violist Michel Samson meedoen in Aylers groep. Dat viel niet bij alle vaste bandleden in goede aarde. De zwarte altsaxofonist Charles Tyler weigerde in een ‘gemengde’ groep te spelen, en keerde direct huiswaarts.

Merkwaardige bezetting

Albert Aylers groep, met onder andere broer Donald Ayler op trompet en Ronald Shannon Jackson of Sunny Murray als drummer, was in 1965 uitgegroeid tot een kwintet, maar eindigde aldus met een klassieke violist in plaats van een tweede saxofonist.

De avontuurlijke muziek van deze merkwaardige bezetting vormde de kern van de klassieke Impulse-elpee Albert Ayler ‘In Greenwich Village’. Het is ook de belangrijkste reden om het ‘Holy Ghost’-retrospectief aan te schaffen: de schijfjes 3 tot en met 5 zijn helemaal gewijd aan de ‘violenbezetting’. De enkele songs die al eens eerder (op een bootleg) zijn uitgebracht, klonken nooit eerder zo goed. Een extra verrassing naast de bijdragen van violist Michel Samson is het gastoptreden van een Ayler-leerling: tenorsaxofonist Frank Wright, in Cleveland. In dit stadium van zijn carrière leek zijn geluid nog precies op dat van zijn meester. Het meegeleverde boekje geeft waterdicht uitsluitsel over het ‘Who’s Who’ tijdens de saxofoonduels.

Jazzrockprobeersels

Hoe je het ook bekijkt, de Impulse-elpee ‘New Grass’ uit 1968 blijft Aylers meest controversiële plaat. Critici boorden de poging om soul, rhythm and blues en jazz tot een spirituele eenheid te vormen volledig de grond in. Fans van het eerste uur keerden Ayler de rug toe, en veel nieuwe fans heeft het album niet opgeleverd: ‘New Grass’ verkocht voor geen meter.

Op de zesde schijf van de nieuwe cd-doos staan ruwe demoversies van een aantal stukken die bedoeld waren als een nieuw begin in Aylers carrière. Al snel wordt pijnlijk duidelijk dat er flink is gerotzooid met het uiteindelijke (gehate) eindproduct. Inderdaad, Mary Parks, alias Mary Maria, schreef de wat naïeve pseudo-religieuze teksten, en ja, voor het eerst sinds 1963 houden de muzikanten netjes de maat, spelen ze een bluesschema en is de muziek als geheel goed te volgen.

Echter, zo duf en onlogisch de plaat ‘New Grass’ klinkt, zo sympathiek zijn de originele demo-versies van augustus 1968. Het valt te hopen dat er in de archieven van GRP Impulse nog originele meersporenbanden te vinden zijn met alle oorspronkelijke muzikale bijdragen van zangeres Maria Mary, rocksichord-toetsenist Cal Cobbs en drummer Bernard Purdie. Het is hartstikke leuk materiaal, toegankelijk, dat wel, maar met een gekke twist. De veelbeschimpte, want bescheten klinkende sixtiesproductie die uiteindelijk werd uitgebracht kan dan eventueel als bonusvulling worden meegegeven op een apart cd’tje.

Vooruitziende blik

De fatale afloop van Aylers leven betreft niet alleen zijn mysterieuze dood. Tijdens zijn laatste grote concert in Frankrijk kwam hij bewust met oud repertoire, en veelgespeelde songs. Waarom deed hij dat? Eindelijk kon hij laten zien waar hij voor stond; er kwam een groot pubiek, er zouden tv- en geluidsopnames worden gemaakt. Ayler wilde zich niet geven. Niet omdat hij het einde voorvoelde, en slechts wilde terugblikken. De tenorsaxofonist was bang dat hij opgelicht zou worden met al die dure film- en opnameapparatuur om hem heen. Achteraf zou hij gelijk krijgen. De twee albums opgenomen bij Fondation Maeght zouden keer op keer worden heruitgebracht, zonder dat de muzikanten er een cent voor terugzagen.

Aylers vooruitziende blik maakt het ons helaas onmogelijk te bepalen waar hij met zijn muzikale carrière heen in wilde in de jaren zeventig. Hij zou 1971 niet halen, en nog steeds is de doodsoorzaak onduidelijk. Contrabassist Steven Tintweiss noemt in het Holy Ghost-boek de nieuwe composities waarmee de saxofonist bezig was, maar laat in het midden om wat voor muziek het gaat.

Brutale losheid