|

|

|

|

|

Articles 2 (1966-1967)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Three Notes with Albert Ayler: Impressions of the New York Scene by John Norris Coda, April./May, 1966, pp. 9-11 - Canada

John Coltrane and The Jazz Revolution: The Case of Albert Ayler by Frank Kofsky Jazz, September 1966, pp.24-25, October 1966. pp. 20-22 - USA

Whither Albert Ayler? by Henry Woodfin Down Beat Vol. 33 No. 23, 17 November, 1966, p. 19 - USA

The New Jazz by Paul D. Zimmerman & Ruth Ross Newsweek, 12 December, 1966, pp. 50-57 - USA

AA! AA? Yeah, AA! by Ted Joans International Times, No. 5, 12-25 December, 1966, p. 6 - UK

The New Jazz—Black, Angry, And Hard To Understand by Nat Hentoff The New York Times, 25 December, 1966, pp. 10-11, 36-39 - USA

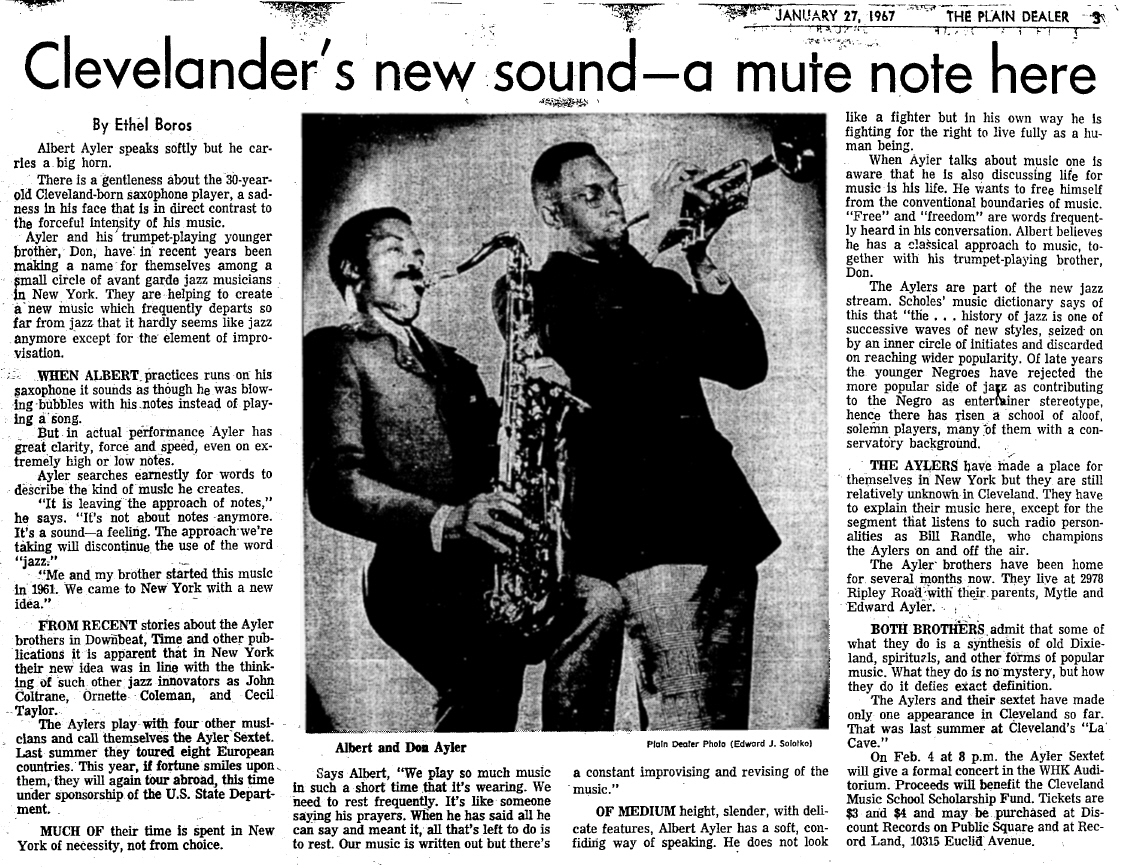

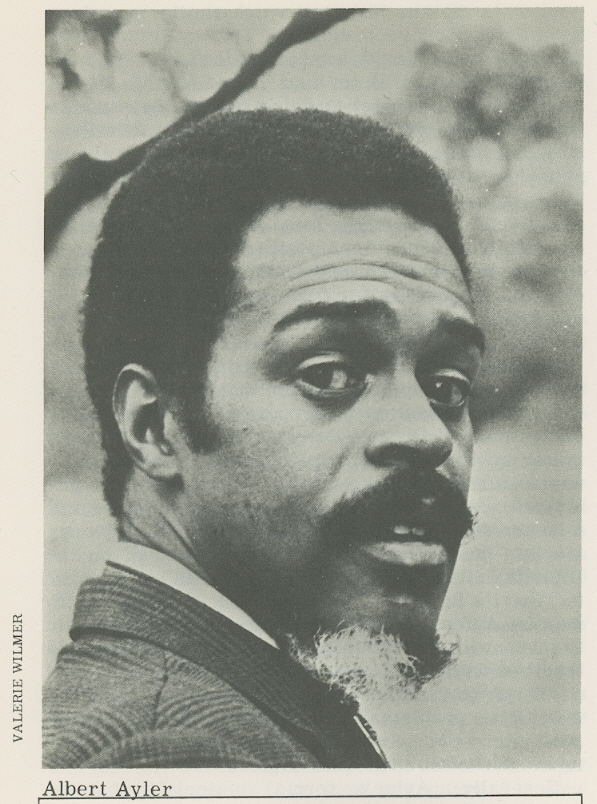

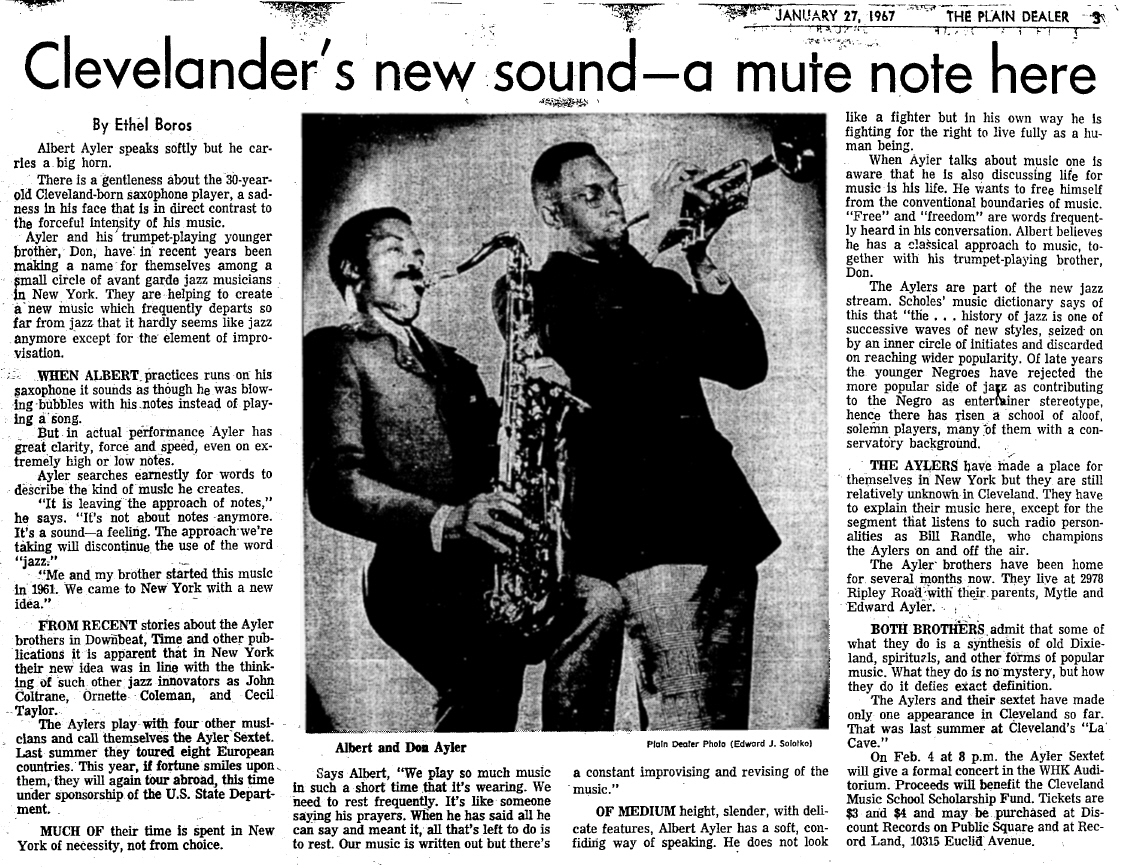

Clevelander’s New Sound - A Mute Note Here by Ethel Boros Cleveland Plain Dealer, 27 January, 1967 - USA

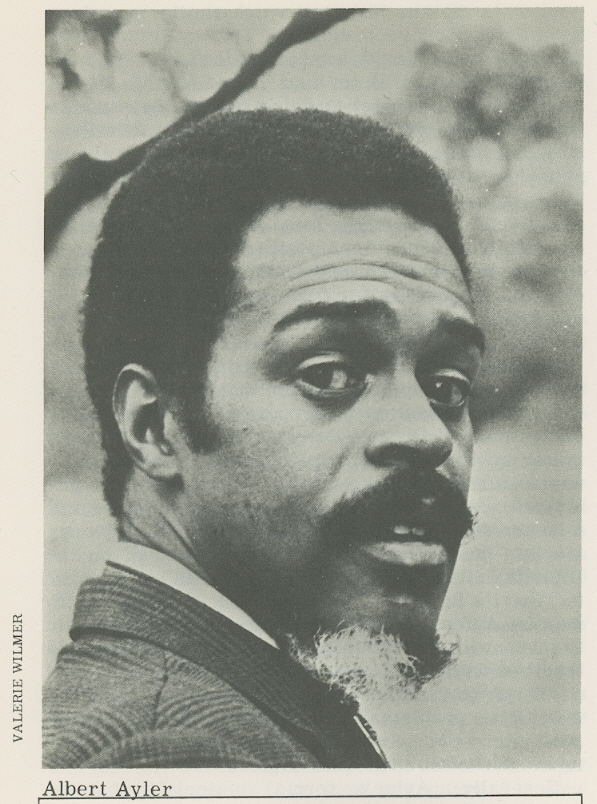

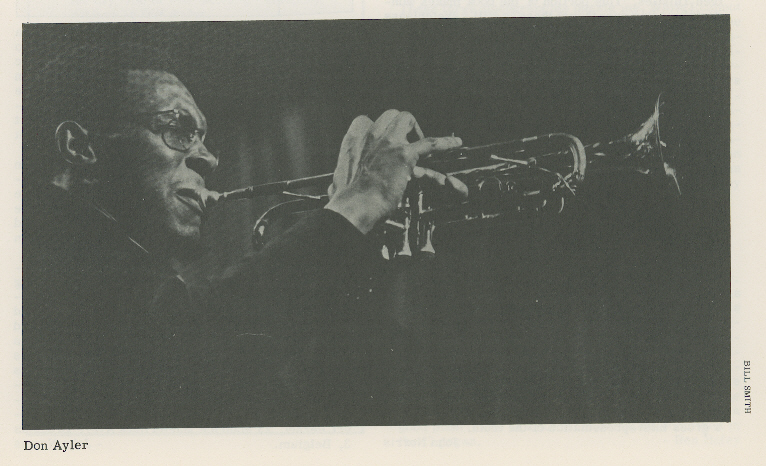

The Ayler Enigma by Alan Barton Jazz Journal, February 1967, pp. 10-11 - UK

La Musique Contre Nous by Yves Buin Jazz Hot, No. 228, February 1967, pp. 26-27 - France

Untitled by Albert Ayler International Times, No. 10, 13-26 March, 1967, p. 9 - UK

Albert Ayler on record: Free Spiritual Music - Part 1 by Stu Broomer Coda, May 1967, pp. 2-5 - Canada

The New Music Scene by Elisabeth van der Mei Coda, May 1967, pp. 28-30 - Canada

Coltrane Is Given a Jazzman’s Funeral Here The New York Times, 22 July, 1967, p.13 - USA

*

Coda (April./May, 1966, pp. 9-11) - Canada

three notes

with

albert ayler

Impressions of the New York Scene

by John Norris

The self-strangulation of jazz has been in the hands of the entrepreneurs for a long time - to the point now where many people really believe that jazz is on its last legs. Possibly this may be true - for the businessman - but for the music it seems to be far from accurate. If the music that was heard recently on a four day visit, is any indication it would seem that jazz is receiving a blood transfusion the like of which it hasn’t experienced for a long, long time.

Without any shadow of a doubt, New York City is pulsating to the sounds of a new music - music that one can hear any day of the week if one has the dedication to seek it out and to become involved with what the musicians are doing. The musicians are struggling to make a living - Slugs and Astor Playhouse concerts can hardly be described as lucrative engagements - but they show a determination and dedication to music that is gratifying. The new music has received little real encouragement from those people best able to expose it and the public at large, in New York would seem to be still generally unaware of what is happening. The release of John Coltrane’s Ascension album (Impulse A-95) and the reorganisation of his band may help considerably in drawing in a wider listening audience. Already a musician such as Archie Shepp is reasonably established. So too is Cecil Taylor but they still don’t get New York club engagements. The owners relying on “safer” musical combinations (such as Mingus, Monk and Rollins - all of whom faced the same dilemma several years ago.)

The “Titans Of The Tenor” concert at the Lincoln Center’s Philharmonic Hall on February 19 demonstrated very clearly the wide gap between what is happening musically and what the jazz audience is prepared to accept. The culmination of this concert was the 40 minute set by John Coltrane’s band - that included Don and Albert Ayler and Pharoah Saunders. The music played was unbelievable. The intensity emitted from the other musicians’ horns made Coltrane’s offerings sound sedate in comparison. The music began with a long, Spanish tinged bass solo from Jimmy Garrison before the music exploded with Coltrane’s familiar “My Favorite Things”. And yet what he played was not exactly the same. He has added a new dimension to his soprano work. It is fuller, more highly vocalised and the impact of his music was helped by the backing, which exploded all around him. Rashied Ali, his new drummer, has to be seen to be believed. His left hand provides an incessant flurry of accents delivered so fast his hands are a blur and the continuous explosive barrage of percussion was unrelenting. J. C. Moses, in comparison, was able to contribute but little and yet he blended well with Rashied’s more complex playing. In addition to this battery of sound, further rhythmic excitement was projected by the other hornmen using tambourines, shakers, maracas etc. It was an insistent and propelling rhythm that sustained itself throughout the solos of all the musicians. Pharoah Saunders’ tenor work was astonishing. His whole solo was in such a high register it sounded like a violin. Following on from Coltrane’s soprano statement it was fascinating to hear.

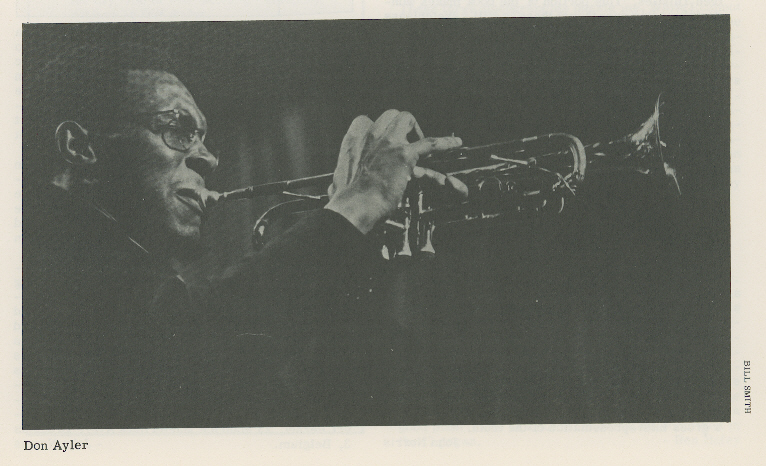

With Saunders and Albert Ayler, the new music has two musicians of diverse but powerful voices. Ayler’s intensely vocal music was beautiful to hear - his tone is virile but sad, and he often moves into voluminous mutterings before returning to relative calm. His brother, Don, is a trumpeter the like of which is rarely heard. His solo work is a violent cleansing of his soul. He practically fights over the instrument as a continuous stream of notes pour forth. Despite the speed of his playing, he manages to emit notes rather than noise. Effective once, as was heard at this concert, his solo work does seem limited, however. He sounded better when he returned with his brother for a remarkable duet.

Their music is hard to describe - in much the same way that it is hard to listen to at first. The thematic material is often naively simple but Albert Ayler plays with facility beyond the legitimate range of the instrument and what he produces are not just freak effects.

Carlos Ward is Coltrane’s new alto saxophonist - a musician who may well make his mark on jazz. He suffered a little in comparison with the other musicians but soloed effectively.

This piece of music by Coltrane’s augmented band, was all solo music. There was no attempt made to produce any real group music. Probably there wasn’t time, for the Ayler’s were only invited to appear a couple of days before the concert. Apparently Coltrane had been trying to persuade the promoters to book Ayler’s own group, but when this failed he solved the situation by inviting them to play with him. It was a fitting climax to a concert that had proved noteworthy in many respects.

Zoot Sims had opened the proceedings with a rhythm section of Roger Kellaway (pno), Bill Crow (bs) and Dave Bailey (dms). Sims seemed slightly below par on this occasion and his sound failed to project into the vastness of this auditorium too clearly. It was pianist Kellaway who took the honours with his solo on The Man I Love.

After three tunes Sims was replaced by Clark Terry and Bob Brookmeyer, who delivered a succinct version of “Straight No Chaser”, in the course of which both hornmen trotted out their favorite licks in their best manner.

It was the first appearance of Coleman Hawkins that produced the first really worthy music of the evening. Stately in appearance, with long grey beard in the manner of an ancient prophet, Coleman Hawkins blew one exclamatory note of In A Mellotone and demolished all that had preceded him. He then dug in and built a long authoritative solo that was noteworthy for its deliberate and forceful direction. Very few of the characteristic Hawkins arpeggios were present and he really produced some beautiful music. This was a jazz master clearly demonstrating that he had no intention of giving way to anyone.

Following intermission, Sonny Rollins came on stage with Yusef Lateef as an additional guest. Lateef opened up with a good solo and then Rollins took over. He proceeded to play a variety of tunes for some fifteen minutes while he walked around the stage, used the wall to alter the tone of his notes, ducked and avoided the spotlight, played behind the accompanying musicians and only occasionally utilised the microphone. It was a good performance and obviously Rollins feels that the visual aspects of his presentation are an asset to his presentation. The music he played seemed somewhat static however. He never once built up to anything that remained in one’s mind. What he played could be summed up as a brief sample of a shuffled together Sonny Rollins Songbook. John Hicks (pno), Walter Booker (bs) and Mickey Roker (dms) were the supporting musicians and they never emerged into the spotlight with the exception of Walter Booker.

It was Coltrane’s music that captured the heart and mind. It left the audience in a state of shock. Few seemed prepared for the barrage of music that soared over them and they remained seated, unable to applaud, even after the musicians had left the stage and the lights had come up.

Albert Ayler’s music produced the most startling and satisfying music of the visit and what he has accomplished is comparable to Ornette Coleman’s breakthrough in the late 1950’s. This man’s music is so completely individual, and yet so strong, it can completely engulf the listener. It can also offend mightily because a casual listen might give the impression of absolute nonsense. Ayler has been playing Monday night concerts at the Astor Playhouse, a small intimate theatre in the Village, not far from the Five Spot. The concerts are presented by ESP-Disk, a record company that has helped considerably in the documentation of the new music.

Ayler’s music is, essentially, group music. The combination of his tenor sax, his brother’s trumpet and altoist Charles Tyler produced a sonorous sound combination of great richness. It is strange that musicians who have such fantastic command of their instruments produce music of extreme simplicity. The themes that Ayler uses are nearly all drawn from the “folk” repertoire of children’s songs, familiar in part to nearly everyone. It is what they do with them that is so astonishing. The music that they play is sometimes startlingly like New Orleans jazz. There is more than a trace of parade style music and the interaction of the three horns produces music similar in approach. An even more startling comparison of this can be heard in Ayler’s recording of Witches and Devils (Danish Debut - English Transatlantic TRA130).

At the Astor Playhouse, Ayler used Joel Freedman on cello and Ronald Jackson on drums as well as Tyler and his brother. The lack of a bass player was never noticed and Freedman’s cello work often became a fourth ensemble voice. Another important aspect of Ayler’s music is that the rhythm is carried by every member of the band and so the necessity of “time” being marked down is no longer there. The role of the drums has altered considerably. Jackson used his entire kit to accent, emphasise and go with the music of the hornmen. Because this music is so volatile and humanly expressive, the tempo is rarely constant throughout a piece - hence a wide variety of moods, feelings and impressions are produced.

This music is in the process of destroying a lot of worn out ideals. By itself, it is something of intense beauty.

Slugs, a neighbourhood bar on the lower east side, has been a regular setting for many of the newer musicians for about a year now. It has served as a workshop as well as a place in which some small measure of exposure can be gained. It’s informality is shaped by the regular patrons - who care little about the music - but it has meant that the music is unaffected by the restrictions of managers nervous of offending the ivy league set. It is a bar that is attended by jazz people - people able and willing to accept the music as it is. Burton Greene is one of the small handful of pianists able to make any contribution to this new music scene. His debt to Cecil Taylor can be heard clearly and yet he demonstrated his ability to build something of his own from within that framework. He was heard in a trio setting. His tenor saxophonist, Frank Smith, had left early. Steve Tintweiss, his bassist, is yet another astonishing young musician now playing jazz. He has a remarkable ear and a beautiful conception. Obviously much more will be heard of him. Dave Grant, the drummer, was an able percussionist. Greene’s piano work will be heard soon on a number of ESP records and his musical sense of humour enabled him to take Twelfth Street Rag and develop it into an exceptional musical composition of his own creation.

Charles Mingus was at the Five Spot and had Paul Bley on piano, Dannie Richmond (dms), Charles McPherson (alt) and Eddie Pierson (tpt). Bley’s ballad solo was the high spot of the two sets heard, along with Mingus’ always superb bass work and his ability to get his musicians to work together. The music never really took off though. It was routine rather than inspired.

The Dom, across the street from the Five Spot, is where Tony Scott presides over massive jam sessions. Ostensibly his group is a quartet - with bassist Henry Grimes being the musical strongpoint. Eddie Marshall is the drummer and on the two occasions we were there a variety of pianists sat in. Don Friedman and Jane Getz produced the best music. The high point was Scott’s duet with Albert Ayler on Summertime. Ayler, using Scott’s tenor, played unison lines with Scott, the latter in the high register of his instrument. It was here, too, that Tony Scott let Ric Colbeck play three notes with Albert Ayler and then decided to ask whether he was a member of Ayler’s group. Scott is trying hard - and the club is attracting people. As a jazz musician he still demonstrates his enthusiastic acceptance of what is happening even though his own contributions remain of lesser interest.

Jazz music appears to be opening up all over New York. All it needs is room to be heard.

[The original pages are available below.]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Back to Articles main menu

*

Jazz (September 1966, pp.24-25, October 1966. pp. 20-22) - USA

John Coltrane and The Jazz Revolution: The Case of Albert Ayler

by Frank Kofsky

[Part One] [Part Two]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Back to Articles main menu

*

Down Beat (Vol. 33 No. 23, 17 November, 1966, p. 19) - USA

whither albert ayler?

BY HENRY WOODFIN

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IT IS OBVIOUS that the new jazz is here to stay. Few young musicians who feel drawn to jazz will be attracted to anything other than today’s avant-garde. In light of this, it is the critic’s central task to try to determine the viable directions the music is taking. It is not the critic’s proper job to engage in partisan tactics on the behalf of some style to which he is personally attached and consign all other methods to the rubbish bin.

The current devotion to “political” and pejorative ranting on the part of both critics and musicians has, perhaps, its own value. But in the meantime, the tasks of explication and evaluation remain.

The development, then, of the new jazz probably depends on the emergence of some dominant figures who will determine its course, as such figures have in the past. Without the presence of such players, the new jazz may well founder in a sea of competing alternatives, none of which may achieve realization if there is no one to pull them together and realize some common style that can be consolidated by the talents of lesser musicians.

The strongest contender for this position seems to be tenor saxophonist Albert Ayler. With this in mind it is worthwhile to consider where he comes from and to attempt to discern where he may be going. With someone who has recorded as seldom as Ayler, and whose public appearances have been so few, the difficulties of assessing his work are considerable.

However, his recording of Summertime provides a good starting point.

It is clear that his technique of melodic development comes, stylistically, directly from the work of Sonny RoIlins and Thelonious Monk. Ayler carefully restructures the George Gershwin melody into a plaintive statement of exacerbated lyricism. He never really leaves the melody; rather he concentrates on a shaping of its contours that amounts to an exploration of its rhythmic and lyric possibilities.

Nevertheless, the presence of a conventional post-bop rhythm section hampers his efforts. The pianist tries to guide him harmonically in irrelevant directions, and the drums only accent futilely, for the obvious fact is that Ayler’s rhythmic manner comes from John Coltrane. He requires a non-timekeeping rhythm section that will provide a thick backdrop of percussion around which he can weave a line that sings with his vibrato and cellolike timbres.

On his ESP trio date drummer Sonny Murray and bassist Gary Peacock give him the type of accompaniment he needs—Peacock plays contrarhythmically and contramelodically to Ayler’s line while Murray’s drums lay down an independent quasi-melodic pattern with which Ayler interlaces his improvisation.

With this sort of sympathetic backdrop, Ayler displays his full talent. The almost hypnotic quality of his harsh, brooding tone and line sets up an emotional ambience of deep, nearly shattering desolation. Spirits and the second version of Ghosts are admirable exhibitions of his skill.

However, it is also apparent that Ayler does have certain problems.

The highly tense emotional atmosphere of the improvisations seems to incline him to rather gratuitous howls and snorts that do not, as similar devices in the hands of Rollins do, further the consistent development of his variations. Rather, they seem like fill-ins to cover the momentary failure of inspiration or planning. They work as fillers, much as the fast runs of arpeggios to which the less skillful—and some of the more adept as well—bop players resorted.

Similar problems of full articulation are to be found in the concert recording Bells. Ayler’s work here seems again fragmentary, although this is offset by those fragments that succeed in consistency and lyricism.

Certainly the merely emotion-charged howls and shrieks Ayler contributes can be considered as errors of the still- maturing musician playing in an atmosphere thick with intense feeling. Nevertheless, one must ask of any performer that his performance be clearly expressed and worked out. The only alternative is John Cage, and I don’t think that is Ayler’s way.

The direction that seems more promising for him—and it demands talent and control—is to work further with the technique of “free” improvisation.

Such a procedure requires that both Ayler and his fellow performers achieve the highest sensitivity to each other and their respective styles. It has been the failure of stylistic congruity that has damaged the attempts at “free” jazz from Ornette Coleman to Coltrane. However, considering the relative novelty of the method, it is still too soon to expect any but the most halting of successes. But it does seem that this sort of approach is the only one that can save the jazz musician from the pitfalls of the repetition of the past and the inarticulate grunt.

Of course, an examination as cursory as this cannot take account of many of the major problems facing both Ayler and the other new jazzmen. For instance, without its traditional audience-base in the Negro community, will the new jazz end as only an imitation of modern concert music? Already its audience is now, in the main, made up of disaffiliated intellectuals and their various hangers-on, and this trend is probably not reversible in any creative manner. Also, the despair and anguish of the music may, in the long run, lead to a deadly narrowness of expression.

But Ayler seems to have a better chance than many of his contemporaries to avoid these perils.

His sense of form has already been well displayed, and it is doubtful that any musician with this feeling for structure can be content with formlessness. His rhythmic skills are not yet fully developed, but the rhythmic deftness of his playing and the ways in which he moves, like Coltrane, through and around an implicit time lead one to think he may be able to go beyond the facile, often arhythmic, work of so many of Coltrane’s followers. The lyricism of his work shows he can do more than echo the agitated emotions of his contemporaries.

Ayler may achieve an art which contains love and hate, despair and fulfillment, tragedy and comedy. If he succeeds, he will, indeed, be an artist to reckon with.

RECORD REFERENCES:

Fantasy 6016: My Name Is Albert Ayler—Summertime

ESP 1002: Spiritual Unity—Spirits and Ghosts

ESP 1010: Bells

Back to Articles main menu

*

Newsweek (12 December, 1966) - USA

THE NEW JAZZ

BY PAUL D. ZIMMERMAN & RUTH ROSS

THE

NEW

JAZZ

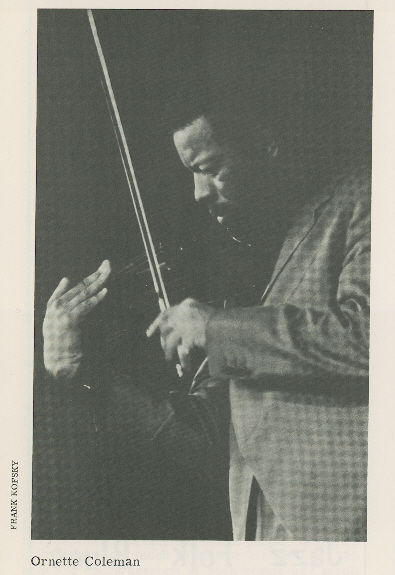

On Nov. 17, 1959, a bearded prophet from Texas named Ornette Coleman carried his white plastic alto saxophone into New York’s Five-Spot Café and blew the jazz world to pieces. The molten, unchained improvisation of Coleman and his waistcoated trio of young musicians confused many listeners and even infuriated many jazzmen. Some walked out in disgust. English critic Kenneth Tynan cried, “They have gone too far.” But Leonard Bernstein leaped to the stand to embrace the new musicians, and advanced jazzmen such as conservatory-trained John Lewis proclaimed Coleman the apostle of a new age. The most violent, ambitious revolution in the history of jazz had begun.

The rhythms of jazz have always been the rhythms of revolution, a personal revolution beyond all ideology and dogma. They were created by the American Negro who could find freedom only in such private and personal rhythms. Ironically, this was his greatest cultural gift to his country and became the most characteristic expression of that country. The history of jazz itself is a history of personal revolutions—the clear, classic, galvanizing trumpet calls of Louis Armstrong; the proud, complex elegance of Duke Ellington; the melodic eruptions of the Bird, Charlie Parker; and now Coleman’s searing self-revelations that triggered what has come to be known as the New Thing. The New Thing is the dominant movement in jazz today, enlisting the energies of a whole generation of remarkable young Negroes and reflecting, as jazz always does, the surrounding tensions of urban America.

Fury:Its forms have been hammered out by the urgencies of a new Negro sensibility—which can produce the anguished sensitivity of a James Baldwin, the civilized sagacity of a Ralph Ellison, the proud dignity of a march on Washington—or the blind fury of a Watts riot. Racial pride, black consciousness, the frustrated anger of the exploited, the cry for equality and dignity and the demand for artistic legitimacy are the new music’s themes. “The jazz revolution is not a programmatic black-power movement,” critic Nat Hentoff points out. “It believes in soul and law and freedom. There’s almost a touching belief in music as a cleansing, purifying, liberating force, as if jazzmen were the unacknowledged legislators of the world. They all want to change the social system through their music.”

The esthetics of the new music is also its politics—freedom. The new jazzmen have ripped jazz from its formal moorings. Like their contemporaries in painting, theater, films and poetry, their art has become nothing but itself—pure sound, spontaneously created under the pressure of feeling and thought—not variations on a theme, not ruminations on a harmonic structure, but pure melody driven by inspiration. This is the music of Coleman and of older men such as pianist Thelonious Monk and tenor saxophonist John Coltrane, who in 1957, he says, “had a vision of the new music but I didn’t know how to realize it. It’s taken various men to make it manifest.” Some of these men are saxophonists Albert Ayler, Pharoah Sanders, Marion Brown and Archie Shepp, the brilliant pianist Cecil Taylor, and composer-pianist-leader Sun Ra whose “cosmic philosophy” and mystical mumbo-jumbo cannot conceal a unique musical talent.

The new jazz is as personal as street cry and as highly organized as the most sophisticated concoctions of the classical avant-garde. Last month at Slugs’ Saloon in New York’s East Village, listeners packed back to the doors heard Ornette Coleman’s trio play the New Thing at its best. From Coleman’s new golden horn, golden sound in endless streams painted the house. Hoots and hollers, dizzy skidding scales, instant, fresh melodies, slashes of sound—then quiet, sweet lamentations in crying harmony with bassist David Izenzon while drummer Charlie Moffett beat out the pulse of this complex new organism. But, always, there was freedom—each man his own composer, creating and listening in a triple loneliness. There were no set harmonies, only the harmonies of crossing train tracks, of melodies that embrace and go their own way. “My music has its own law and order,” says Coleman. “I don’t have to create from the old patterns.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

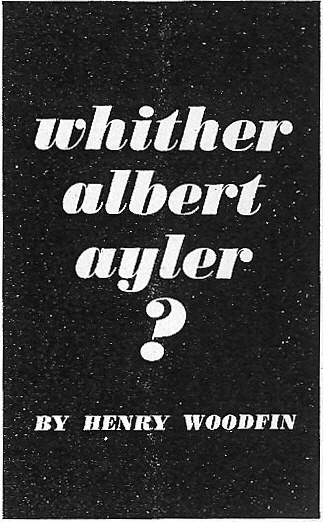

—Jill Krementz

Izenzon and Coleman: ‘I feel I can add to American culture’

|

|

|

|

Hurt: He first started framing this new order in the 1950s in California and paid in blood and pain to enforce it. “The style being played in those days was more or less new melodic lines built on old chord structures. When I started composing my own melodies right on the spot,” recalls Coleman, “they kept throwing me off the bandstands. I wondered what I was doing wrong. But the only thing that was really wrong was that the guys didn’t know what I was doing. I remember four very famous jazzmen in Los Angeles let me play with them. Five seconds later they all walked off and left me alone before 500 people. I kept wondering why I shouldn’t play the way I want as long as it didn’t harm anybody. I was very hurt.”

Coleman’s whole effort as a musician and a man has been to put this hurt behind him, and a thousand other hurts— his Jim Crow, dirt-poor Texas youth, his vicious beating in Baton Rouge in 1949 by locals who resented his music, his brutal bandstand snubbings. “The present begins when I start playing my music,” he says. “We have to create a present that justifies what we are and what we do. I do that in my music. Living in the present without letting the past affect you is the hardest thing you can imagine. A white American can wake up in the morning without having any past on his mind. But I can’t, at least not yet. Persecution stays in the memory.

Barrier: Coleman, 36, has survived his past unembittered. He jokingly calls his life “the American nightmare” and “a very, very sad story,” but there have been rewards, too. “I’ve gotten the most ridiculous letters from people who put down my music,” he recalls, “and later they come up to me and hug me on the street.” But his ultimate aspiration, to make a lasting contribution to the culture of a color-blind America, is as distant as ever. “White people tend to see me as a Negro first, then as a human being. That creates a barrier. I feel I can add to American culture and help uplift it. I don’t want to be condemned by white people who are worrying about Negroes in general. If they can’t look for the pure human values first, they ought to move out to another planet.”

Some of the new musicians, however, insist on their blackness as part of a larger movement to reappropriate jazz as an exclusively Negro art. “Black music,” says fiery, Negro poet LeRoi Jones, “is the music black people make. It’s a translation of the black man’s experience into music.” Jones’s definition pointedly excludes all white jazzmen who, he thinks, can only play a tepid imitation of the real thing. “Stan Getz makes a million and Lester Young dies in poverty,” he says. “Barbra Streisand steals from Lena Horne. Leonard Bernstein was at my house one night. I asked him why he made more money than Duke [Ellington]. Did he think he was a better conductor than Duke, a better arranger than Duke, a better composer than Duke? I told him he didn’t even dress as well as Duke. And he got up and walked out. The white man puts a straw in our brains and sucks out the juices. He makes our music his own the way a thief makes your money his own: he takes it.”

White musicians, who have always viewed jazz as a cooperative effort in which white and black borrow from each other liberally, reject Jones’s divisive terminology. “What does he think Bix Beiderbecke was doing?” asks veteran clarinetist Pee Wee Russell. “Beiderbecke listened to everyone and everyone listened to him and they took it from there. The real greats in jazz never had any feeling about ‘black music’ or ‘white music’.” Bassist David Izenzon, one of a handful of white musicians who play the New Thing, answered Jones this way: “I have a few thousand years of tradition to contribute myself. Since I’m white and Jewish, perhaps a Jewish guy is going to realize when he sees me up on the stand with black musicians that this new music has something to do with him.” “The white man has to prove himself in any Negro context,” says trombonist Bob Brookmeyer, who plays in the new, integrated Mel Lewis-Thad Jones Band, “and that’s the way it should be. In this respect, the Negro gives the white man a better shake than the white man ever gives the Negro. I don’t care much for being a white person. There isn’t much to be proud of.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

—Charles Shabacon

John Coltrane: ‘It goes deep’

|

|

|

|

Crutch: Even most black musicians won’t endorse Jones’s musical apartheid. Jones proclaims, “We are a nation of musicians,” but trumpeter Miles Davis who has always worked with whites, disagrees, saying: “We just don’t have no natural rhythm. I tried my damnedest to get some rhythm out of two black cats I know and I’ve got two hernias to prove it. In fact, I only know five drummers who can keep time. They ought to get off that black stuff. It’s a crutch.” Coleman agrees: “It’s a lot easier to yell than to make good music. Today every black guy with a horn says he’s avant-garde. That’s a lot of crap. He may be black but that doesn’t mean he’s avant-garde. It’s the same for electronic composers. They’re not all avant-garde geniuses. Hell, anyone can blow a fuse.”

Edge: But Jones’s appeal is not to the black musician’s logic, but to his growing racial pride. The new jazzman no longer considers himself a Stepin Fetchit entertainer but an artist with the right to the respect paid any artist, white or black. “You can feel this new pride in the spirit of the music,” notes critic Hentoff. “You can see it in the way these guys come out and play. There’s nothing deferential about them. They seem to be saying ‘Keep quiet and listen’.” Archie Shepp, the 29-year-old tenor saxophonist whose sound cuts through the listener like the edge of a broken bottle, shares Jones’s belief in jazz as an educational force that tells the Negro who he is, where he came from and where he must go. “My music says poverty,” snaps the goateed Shepp. “It’s designed to move my people to change their condition. My music must revive in the mind of my people the image of the rain forest with all the dignity that was always there. My music tells my people to stand up and liberate themselves and that I stand with them.”

Behind this cry for revolution lie more practical demands—the chance to play, the need for money and recognition and the age-old contention that jazz is as worthy of public support as classical music. “When you talk about a civic orchestra or symphony, nobody expects them to make money,” says Shepp, who had to feed a wife and three children on an income of $3,000 last year. “It’s only when a nigger enters the picture that he has to make money.” Cecil Taylor agrees: “The day before we left for Newport last year we were rehearsing at the home of a café owner in New York. When his wife heard us she told him you can’t permit this. Had we been a string quartet, she would have considered it a cultural feather in her cap to have us practicing in her building.”

Taylor’s life has been a horrifying series of harassments by club owners, horrible pianos and economic barrel- scraping. “I can’t see for the life of me,” he says, “why the public can’t accept the idea that musicians involved in improvising all their lives can produce music as equally valid as any other.” Jazz, he believes, never really reaches the public. “You can’t have the real Negro image coming in on television when the wife and kiddies are seated at the dinner table. It’s all right to have Negro ballplayers or Sammy Davis, our modern Stepin Fetchit. But,” says Taylor, the “real Negro” with his new music has a message for everyone, “a revolutionary concept of what life is all about—living and enjoying it and enjoying the serious choices to be made.”

Ugly: Shepp and Taylor spend their time tangling with the most visible obstacle to their livelihood, the club owner, demanding high salaries for jobs and cursing the club owners as racists when they refuse. “The ugly thing about these cats is that they think they’re music critics,” says the embittered Taylor, a small, almost feline figure with a mournful mustache. “For them to think of us as artists is out of the question. As far as they’re concerned, we’re products. We’re there to sell drinks for them.” The club owners offer a simple defense. The music does not draw. “I’m not in the philanthropy business,” says Art D’Lugoff, owner of New York’s Village Gate. “It’s just like a restaurant. I can’t afford to serve a losing item. There’s no conspiracy against these guys. Their music just hasn’t caught on. That’s all. They’re paranoiac.”

Many seasoned jazz observers, like the “Jazz Priest,” the Rev. Norman J. O’Connor, who has involved himself with the problems of jazz musicians, believe that Shepp and Taylor and the other new musicians suffer more for their convictions than from their color. “They’re being completely what jazz musicians ought to be,” says the genial, silver-haired Paulist priest, “complete improvisers who pay dues to nobody but themselves. Ellington and Miles Davis have done this in a way, but they always know where their audience is and never put themselves so far out that you can’t reach them. But guys like Coleman and Taylor have stepped over the line and said ‘You follow me’ and, unfortunately, very few have followed.”

It takes sympathy, education and an open mind to follow the new musicians whose shattering sounds offer as little familiar ground to the traditional, foot-tapping jazz fan as the works of Jackson Pollock afford the devotee of impressionism. The music is rich, violent and, at first, hard to listen to.

Hunt: When Don DeMicheal, editor of Downbeat magazine, heard Coltrane’s new group “It repelled me. I hated what they were playing—those drums and maracas and bells and tambourines.” But DeMicheal changed his mind: “I do not pretend to understand this music,” he says now. “I doubt if anyone, including those playing it, really understands it, in the sense that one understands, say, the music of Bach or Billie Holiday. I feel this music . . . it opens up a part of myself that normally is tightly closed, and the seldom-recognized feelings, emotions and thoughts well up from the unconscious and sear my consciousness. Parts of Coltrane’s music are aural reflections of what I believe lies deep within each of us—the chaotic, brutish, wrenching torture chamber of humanness.”

It would be hard to find men more talented and dedicated than Coleman, Coltrane, Taylor and Izenzon in any art. But jazz has always been dismissed by the foundations and cultural philanthropies in their hunt for worthies. “We have nothing under consideration at this time for the new jazz,” says W. McNeil Lowry, Ford Foundation vice president. “We consider it a legitimate part of the arts but nobody has come forward with a proposal about what we might do for this handful of musicians. We’ve always felt that jazz offers a much easier commercial place for an artist than a lot of the other arts.”

Most jazz musicians die poor searching for this easy place. The 75-odd companies that record jazz make up less than 10 per cent of the total record market, according to Billboard magazine. The club situation is even worse, since only a handful—Slugs’, the Village Gate, the Village Vanguard in New York, the Plugged Nickel in Chicago and San Francisco’s Jazz Workshop and Both-And—are open to the avant-garde. “It’s a master-slave relationship,” says Coleman about the club and record situation. “The producer wants a happy slave and thinks he knows how to do it. But all he really wants is the slave’s music.” Sun Ra, whose Solar Arkestra of eleven players split $117 for five hours’ work at Slugs’ last month, draws even less from his records. “One record we made for Savoy,” he says, “has paid me $6 in five years.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

—Benno Schapira

Sun Ra and Arkestra: Beneath the mumbo-jumbo, music

|

|

|

|

Mythology: If Sun Ra is neglected by the impresarios, he is honored by many of the new musicians. “He’s our Basie and our Ellington,” says Marion Brown. “He plays the piano but his real instrument is the orchestra.” A gray, soft, rounded man in a beaten gold shirt and red pants, Sun Ra lives in a broken-down apartment near the Bowery embellished with “cosmic” paintings, plastic spheres and rubber balls suspended by string. He has created an entire universe out of Woolworth leftovers in which he is the sun god. “Ra is the mythical sun god of Egypt,” he explains. “At football games they holler my name—Ra, Ra, Ra—because they want victory.”

Like Shepp, Sun Ra wants to reach Negroes with his music, but he is a severe taskmaster for his people. “I couldn’t approach black people with the truth because they like lies. They live lies. They say ‘Love thy neighbor as thyself’ but I don’t see them doing that. I don’t think of Negroes as my brothers.” Right now, Sun feels, the Negro wastes himself playing toady for the white man. He wants to change that with his music. “I’m a demon,” he says almost casually. “They respect that. I’m going to beat the superficiality out of them. I’m going to beat them and beat them and beat them. If you see me playing before black folks, you’ll see they’re uncomfortable because I’m playing beauty and they’re ugly. I can cleanse Negroes and whites too with my sounds. A. good brainwash would be lovely for them.”

Gifts: Sun Ra places his itinerant childhood in “Alabama, Virgin-ja and West Virgin-ja,” where he found, as a child, melodies in his head that needed writing down. Later, in Chicago, he grew up on the music of Ellington, Earl (Fatha) Hines and Armstrong. “In Chicago, I played in Fletcher Henderson’s band. I was playing my avant cards but Fletcher still liked what I was doing.” And Sun Ra adds, “I have astro-infinity gifts to offer, solutions for all people and all nations concerned. I’m playing for the whole planet. I’m supposed to do the impossible, demonstrate to the people that there is something beyond the God they have been worshiping. My music is about friendship.”

At his five-hour concert at Slugs’ Saloon last month, the sun god unleashed the full fury of his art and anarchy before a small, spellbound, sober audience of some 100 devotees. Boxed in on a tiny stage, Sun sat kingly at the piano, his head crowned by a cap of gold, his drummer backed against the backdrop curtains, his bassist hunched over his instrument. The rest of the Solar Arkestra—so called because “people pronounce it ‘arkestra’ anyway”—were forced to crouch along the edge of the stage, hardware in hand—trumpets, French horn, trombone. The program included everything from lush pastoral hymns to solid jazz and wildly improvisatory numbers. A motion-picture projector bathed the musicians in rotating orbs of light and they became African astronauts playing to the cosmos. “We need to get off this planet as fast as possible,” says Sun. “We’d better be out there when here blows up.”

Sun Ra writes down most of his music but sometimes “I send out my waves to the soloists and they play a continuation of what I would have played, what I would have written had I had time. They have to read my mind.” He has gathered many of his musicians from HARYOU-ACT. “I look for the incorrigibles,” he explains. “If they don’t fit in with someone else, they’re gonna come back to me. That way I don’t have to worry about keeping a band together.” His counsel to his young musicians is this: “If you’re going to hate, start hating yourself. You can’t move out into areas of infinity with all these emotions. They slow you down. You have to be more pliable than a child. You have to be completely unrebellious.”

A crucial part of the new jazz revolution turns on the search for a new, dignified setting for jazz in which the jazz musician is not exploited to sell drinks. “I would like to play for audiences who aren’t using my music to stimulate their sex organs,” says Ornette Coleman. “I find that concert audiences don’t use my music that way. A nightclub is not where jazz gets its best audience because it’s still based on getting drunk enough to go after the flesh nearest you.” Jazz has been moving into the concert halls and the colleges. Coleman, Cecil Taylor and Sun Ra completed campus tours recently and, in New York, the 2,600-seat Village Theater has become the scene of rousing New Thing concerts. “Musicians,” proposes the young saxophonist Lee Konitz, “have to set up their own place that’s open 24 hours a day and gives every band a chance with the groups splitting the door money. It would be great to know there’s a place to hear jazz anytime.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

—Omar Kharem

Shepp: ‘My music says poverty’

|

|

|

|

Haven: Forty-year-old John Coltrane, the spiritual leader and father figure of the new jazz, may provide the unharassed haven the new jazzmen want. “I’m thinking of opening some kind of place where I could play whenever I felt like it and could invite other groups,” he says. Coltrane’s play-when-you-feel-the-spirit policy fits in nicely with his new musical aims. “My goal,” says the gentle, reflective Coltrane, “is to live the truly religious life and express it in my music. If you live it, when you play there’s no problem because the music is just part of the whole thing. To be a musician is really something. It goes very, very deep. My music is the spiritual expression of what I am—my faith, my knowledge, my being.”

The younger jazzmen revere Coltrane. “I was playing this concert,” recalls Marion Brown, “and when I’d finished a solo, I backed off the stage. There was Coltrane with the lights behind him, beatified. He held out his arms and took me in and I wept like a child. I’d been through so much and held so much in, but I didn’t cry until Coltrane told me I was all right.” The gaunt-faced Brown expresses most simply the cry for legitimacy of the new jazzmen. “When people hear the word ‘jazzman,’ the first thing they think is unemployed, then dope and sex, but the young guys aren’t like that anymore. I’d like a girl to be able to take me home and introduce me to her parents and hear them say, ‘Oh, jazzman, isn’t that fine’.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

—Al Hicks

Cecil Taylor: No place to play

|

|

|

|

|

Ebullient: The prospect of jazz returning to the mainstream of American music is remote. The new musician might want the respect of the establishment but they are not willing to cater to establishment tastes. Coleman, Coltrane, Taylor, Shepp, Brown and Albert Ayler are pushing the revolution further and further away from the accepted landmarks of two- four time, blues harmony, simple melodies and sweet, soothing sounds. “To me,” says the bearded Ayler, whose ebullient “Ghost” has become an unofficial anthem of the new music, “conventional jazz is a joke.” He expresses his amusement in the Southern church-band tunes he works into his whinnying, boiling solos built like collages out of bits of this and that—blues, Dixie, gospel.

Some years ago French composer-critic André Hodeir wrote: “Though today it is appreciated only by the happy few, the most advanced jazz has already launched invisible missiles in the direction of its future audience.” That audience, like the audience for everything that is new in all the arts, is growing, and it is an international audience. Ornette Coleman was a hero in Sweden, John Coltrane was strewn with flowers and paraded about the streets of Tokyo, and in a recent tour Albert Ayler was lionized in Berlin, Holland and France.

What this young audience wants is the perennially young sound of jazz—the sound of America, a young country, and increasingly the sound of young energies everywhere. It is the sound of human possibility. Last week Ayler described what it feels like to be up on the stand in a club, the lights low, the smoke thick, the ice tinkling in glasses, the spotlight searing like a burning glass. “Yeah, yeah, that’s it. Right after that first sound comes, I just give all that’s in my heart to give—just give it all. I’m livin’ it, breathin’ it, drinkin’ it. I’m out in another dimension and I’m hummin’ a tune. I never stop. I’m hummin’ a tune when I’m talkin’ to you.”

Back to Articles main menu

*

International Times (No. 5, 12 - 25 December, 1966, p. 6) - UK

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Back to Articles main menu

*

The New York Times (25 December, 1966, pp.10-11, 36-39) - USA

The New Jazz—

Black, Angry, And Hard To Understand

By NAT HENTOFF

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Back to Articles main menu

*

Jazz Journal (February 1967, pp. 10-11) - UK

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Back to Articles main menu

*

Jazz Hot (No. 228, February 1967) - France

A propos du passage d’Albert Ayler au IIIe Paris Jazz Festival, Yves Buin répond à Jef Gilson et Claude Lenissois après leur prise de position résolument hostile

LA MUSIQUE

CONTRE NOUS

Je n’ai pas eu l’occasion de connaitre — autrefois, on aurait dit l’honneur — Jef Gilson et Claude Lénissois. De Jef Gilson j’ai apprécié — compte tenu des conditions difficiles de la naissance et de l’existence d’un jazz français — les divers albums publiés par le Club de l’Echiquier, j’ai assisté au Concert d’Antibes en 1965. Il a reçu, en outre, ma pleine adhésion, lorsqu’il déclarait — mais peut-être lui a-t-on prêté cette phrase? — à propos du « Glass Enclosure » de Bud Powell, que c’était là le plus bel enregistrement de piano de l’histoire du jazz. Je comprendrais, néanmoins, que l’intérêt que je porte à sa musique ne procure à Jef Gilson ni chaud ni froid. Quant à Claude Lénissois, je ne peux prétendre le connaitre après les quelques phrases de clarinette basse, jouées à l’unisson, que j’ai entendues de lui.

Mais, soit. Nous avons deux musiciens, forts de cette qualité, qui nous parlent de musique. Or, ce qu’eux n’admettraient jamais d’un critique, ils sortent leur revolver. Nous nous attendions à une adhésion ou bien à une contestation argumentée, voire à la détestable prudence du juste milieu, nous ne rencontrons que le mépris. Un mépris total exprimé en termes infâmants. Nous croyions nous entretenir de musique, nous nous trouvons en pleine subjectivité: « Nous, on n’a pas aimé du tout ». Point à la ligne. Alors, subjectivité pour subjectivité, moi, j’ai aimé, bien aimé. A en croire nos auteurs, je suis donc à ranger dans la catégorie « des inconditionnels qui ont peur d’être dépassés et se roulaient avec plaisir dans le caca ambiant ». Vais-je me sentir offensé? Non. Quand on le prend de si bas, il faut s’efforcer de rehausser un peu l’affaire.

Donc, Gilson et Lénissois, je vous admire vraiment beaucoup. Vous avez du courage. Cela dit sans arrière-pensée. Vous étranglez Ayler — devant l’histoire. (Remarque en passant, vous n’aviez personne en face. Erhenbourg, lui, un jour, a trouvé André Breton sur sa route. Il a compris qu’on ne pouvait pas écrire n’importe quoi.) Enfin, vous prenez la responsabilité du fossoyeur. Vous dites tout haut ce que beaucoup pensent tout bas.

Les écrits restent, vous le savez. Aussi, en lisant vos quelques lignes dans « notre » revue, j’ai eu envie de chercher un précédent dans l’histoire de la critique musicale. Mais, vous m’excuserez, je ne suis pas sérieux, bien moins qu’Albert Ayler dont vous trouvez le sérieux effarant. Je n’ai pas eu le courage de consulter le répertoire des 253 582 erreurs de la critique musicale. Mais souvenez-vous par exemple de ce que le plus célèbre critique parisien de l’époque — parait-il — a reproché à Berlioz: d’amener sur scène, ses vaches, sea boeufs, ses chèvres et leurs clochettes. Le critique est tombé dans l’oubli, en poussière. Mais Berlioz? Vous avez aussi en mémoire le ton de ceux qui accueillirent en 1954, à Paris, « Désert » du grand Edgar Varèse. Avouez que vous êtes en terrain familier et que vos termes sont aussi peu appropriés à l’esthétique que convaincants. En effet, nous passons du « caca » — déjà cité — au « borborygme », en passant par « le gâtisme précoce ».

Je vous admire donc, de vous engager aussi résolument, de vous en tirer en mettant de votre côté les gens « sensés » et de l’autre les gogos en mal de snobisme. Mais il n’y a pas de grand courage, il n’y a que de petits courages. Vous auriez pu avoir celui d’aller raconter à Ayler ce que vous nous livrez maintenant. Votre ton, votre intransigeance vous y autorisaient. Peut-être l’avez-vous fait? Alors, chapeau bas. Sinon, c’était possible. J’ai été témoin à Antibes d’une telle rencontre. Un amateur après « Love Supreme » est venu voir Coltrane et lui a dit ce qu’il pensait de sa musique. Cela donnait: « Je n’aime pas du tout votre musique. Vous ne faites que gamme sur gamme, etc. ». Coltrane lui a répondu: « Voulez-vous que je vous paie votre place » et de sortir son portefeuille. Puis, ils ont continué. Un peu. Un dialogue, en somme. Je doute qu’Albert Ayler ait répondu à vos « critiques », de même qu’il se fout et ne lira sans doute jamais ces lignes. Peut-être eut-il aimé votre franchise. Cela semble son genre, comme on dit. Il n’attend rien de nous. Vous allez hurler, mais sa musique n’est pas pour nous. Il ne cherche pas à nous convaincre. Il vient, il joue. A prendre ou à laisser. Alors, me direz-vous, pourquoi joue-t-il à Paris, chez nous? Eh bien tout simplement parce que pour certains organisateurs — qu’ils l’aiment ou ne l’aiment pas —Albert Ayler est un des points d’ébullition du jazz contemporain. Détestable à un concert, Ayler, c’est toutefois « My name... », « Ghosts », « Spirits Rejoice », etc. Déplorez-le, vous en avez le droit. Laissez d’autres se réjouir sans les traiter d’ « inconscients ». Ils vous rendront la pareille et, comme vous le aupposez, nous continuerons de voler très haut.

A la réflexion cependant Albert Ayler est en avance sur vous. Comme Rimbaud, il a mis la beauté sur ses genoux et il l’a assassinée. Car — peut-être n’en conviendrez-vous pas? — notre beauté pour certains Noirs d’Amérique dont Ayler, c’est de la foutaise. Ils en ont fini avec la musique ensemble de sons harmonieusement organisés. Ils ne sont pas les seuls, je le concède. Pour Ayler, la musique ne s’apprend plus — (s’y est-elle d’ailleurs apprise un jour?) — au conservatoire. Il sait que la musique dépasse La musique. Rassurez-vous, je ne ferai pas d’Ayler un révolutionnaire. Vous parlez d’avant-garde. L’avant-garde, terme politique, appliqué à une organisation de classe, n’a jamais été valable en terme esthétique. L’employer ne mène qu’à la confusion. Plus simplement, Albert Ayler m’apprend « quelque chose » sur les Noirs américains. Comme Coltrane, Shepp, Cecil Taylor ou Coleman. Quoi? me demanderez-vous. Evidemment, je pourrais vous répondre avec des effets de manchette, citer Lukaks, parler de ce qui lie épanouissement, raffinement et décadence. Mais j’y renonce. Et puis, Comolli a mis tout ça en forme et si bien. Je préfère vous dire qu’Ayler et Cie réveillent « quelque chose » (encore une fois), en moi que je ne trouve nulle part ailleurs. Ni dans notre musique, ni dans notre poésie, ni dans notre littérature. Et ce fluide — peut-être insipide, je vous l’accorde — me porte à croire que Shepp, Taylor ou Ayler, bien sûr, sont plus vrais (1) que la plupart de nos grands contemporains occidentaux, cet avis n’engageant que moi d’ailleurs. Vous voyez, je vous donne de belles armes, à vous maintenant de refuser le marais subjectiviste, du haut de la musique. Mais vous n’éviterez cependant pas les choix que vous imposeront tôt ou tard et dès maintenant, la « New Thing », la « bande » à Coleman et Taylor, aussi hétérogènes soient-elles. Le jazz vous a été repris, il nous a été repris. Rollins l’a repris à Getz le 13 novembre (2).

Oui, quand on compare Getz et Rollins, l’hésitation — hors du bon plaisir — n’est pas possible. L’un, grand musicien arrivé, comédien, maniant son public de ses clins d’oeil démagogiques, l’autre solitaire indifférent, avec sa musique. Rollins, Taylor, Ayler vous disent, vous devriez le comprendre, que vous avez à faire le jazz que nous attendons — pas celui de Getz, mais celui de Bix ou de Charlie Haden: le jazz des blancs. Et n’allez pas me parler de racisme à rebours, c’est un vieux refrain celui-là. Bob Dylan lui, n’a pas chanté à la manière de Big Bill Bronzy. Il a « inventé » un blues des blancs. Au lieu de cela, vous constatez, vous musiciens et non sans plaisir, qu’une partie du public a quitté la salle. A votre place, je me méfierais. Comme le rappelle Michel Delorme, la même mésaventure est arrivée à Bernard Vitet et Barney Wilen très récemment. Comment pouvez-vous approuver ce poujadisme latent d’un certain public qui transforme son incompréhension, l’abime le séparant du créateur, en un médiocre folklore. « A moi, on ne la fait pas. J’ai payé, je dois être servi ».

La « bande » à Taylor et Coleman possède encore une qualité que voue méconnaissez ou ne comprenez pas ou bien encore dont vous ne voulez pas parler. La violence nue. Elle vous manque. Je ne vous le reproche pas. Je suis comme vous. M’avez-vous vu participer à une bataille d’Hernani ce dimanche 13 novembre? Vous ai-je provoqué en duel? Non. Il y a fort peu de chances que je meure pour la musique. Mais Shepp, Coltrane... Ayler sont pétris de la meilleure violence qui soit: celle du tout ou rien (blanc c’est blanc, noir c’est noir), celle de la dérision (Dada mènera au surréalisme, l’anti-musique à la musique), celle de la désillusion, de l’incommunicabilité, gouffres creusés par d’autres mains blanches que les nôtres. Cette violence, tout comme Trotsky le notait à propos de la morale, fait que « leur musique n’est pas la nôtre ». Allons-nous empêcher ces jazzmen si déconcertants de faire de leur musique le chant des partisans ou bien de décréter la mort du blues? Le fluide dont je parlais plus haut, c’était cela la violence. Une violence — je vous l’accorde — qui côtoie le chaos. Toujours est-il que le Free Jazz en France est né de cela aussi: notre violence, aussi informulée et informulable soit-elle. Nous avons Chautemps, Wilen, Vitet, Thollot, Tusques, Portal, etc. De quoi va-t-il se nourrir, ce Free Jazz? Je ne le sais pas plus que vous ne le savez pour Ayler, d’un scandale aussi fort que le racisme sans doute. Lequel? La crise du marché des frigidaires, Brigitte Bardot présidant un meeting de Tixier-Vignancour, la grève de la régie des tabacs. Qu’en sais-je?

Quoi qu’il en soit, Ayler nous a pris au piège. Vous écrivez, je vous réponds. Que vous le vouliez ou non, il est exemplaire. Il ose ce que Shepp et Taylor (Cecil) n’osent pas encore: l’émotion dans la dérision totale. Vous touchez juste une seule fois, lorsque vous en faites un adepte du néant. Mais vous êtes péjoratifs. Oui, Ayler prend la forme d’un phénomène négatif, peut-être suit-il une impasse encore inexplorée que l’avenir comblera. AYLER nie. Nous sommes d’accord. Pour vous, il n’en restera — et encore — qu’un peu de sable que le vent balaiera. Pour beaucoup — et Ayler n’est pas le seul — c’est une négociation fondamentale qui appelle une affirmation non moins fondamentale. La fin d’un monde et la naissance d’un autre. Quand allons-nous perdre pied avec tout ce qui se prépare, se fera ou ne se fera pas? J’aurais aimé que vous vous posiez la question, pour nous tous, devant ce premier météore. Mais vraiment, à vous lire, on songe que la musique est une chose trop sérieuse pour n’être confiée qu’aux musiciens.

Yves BUIN.

__________

(1) Si vous me demandez ce que signifie cette « unité », je vous renvoie à Luigi Nono qui, en tant que musicien, s’est interrogé sur la Finalité Sociale de sa musique. Cf. « Nouvel Observateur » no 99 et « La Sinistra » no 1.

(2) Et à ce propos, je m’étonne que vous n’ayez oui que « quelques rares interventions » de Sonny alors qu’il a improvisé longuement, trop brièvement, certes, à notre goût commun.

Back to Articles main menu

*

International Times (No. 10, 13-26 March, 1967, p. 9) - UK

ALBERT AYLER

When music changes, people change too. The revolution in jazz took place a long time ago. But, just this year, something happened. Everywhere people are asking, “What’s happening, what’s happening?”

Today it seems that the world is trying to destroy itself. And nevertheless many people succeed in judging the world with an objective view. They see unkindness, hypocrisy, injustice and hard labor that enables a human being to earn very little. If only we really wanted to think of these things, to go into our inner-spiritual-consciences with them, we would understand that we have to fight an endless battle (with ourselves), before winning over all the obstacles, before having acquired the true desire to change.

The music we are playing today will help people to know themselves better and to find inner peace more easily. Inspiration is necessary to all of us. It can come from a word, a paragraph in a book, a painting, from a poem, a song, from numerous things, in short. But actually, nothing can really happen if you’re not ready.

The music we play is a prayer, a message coming from God. We all share the same emotion, but this emotion manifests itself differently according to the personality of each of us.

Unfortunately for us, decor can provoke vulgar emotions in us, such as envy, covetousness, resentment and contempt.

A good many people are not touched by the Holy Ghost. The Holy Ghost will lead all of us through the world someday. Look at the history of jazz; Bolden, Armstrong, Bird, Monk, Coltrane, Taylor, Ornette, etc. all had their own way of seeing things, all had new ideas, the hope of a new aesthetic which wouldn’t know destruction, which neither power nor the established structure would be able to kill.

The soul of each of us–the ideas of God are everywhere and His Spirit is always present–must achieve harmony and supreme goodness through His grace.

The sublime ideas of God are everywhere (I should sooner say that a certain idea of perfection makes a way for itself). The Holy Ghost has been favorable to me. Music is one of the gifts God has given to us. It should be used for good works. We should always thank the Lord; then, we will understand how rich His blessings are in spiritual value and in truth. We must let the sacred spirit of God enter our bodies and keep it there preciously.

That’s why a creator (or perfect man) is a being in spiritual communion, whose ideas are in total harmony with God. For me, the only way I can thank God for His ever-present creation, is to offer Him a new music imprinted with beauty that no one, before, had heard.

This is the only thought that will make me a free man, beyond the limits of the material.

Freedom isn’t the privilege of a single generation; it’s a conquest which must each time be undertaken over again. Freedom is victory.

Those who have found Truth are able to communicate Love, to help those who suffer, people of the Earth as I call them. That the will of God be done, not that of men and women. The will of God is always loving and truthful; it includes harmony and generosity; it permits freedom and is always constructive.

When we let the will of God produce itself in us, we will work with Him, and will be blessed in all of our actions. He will also help us to think justly and kindly.

When all the people understand what links them spiritually to one another, Peace will reign on Earth.

All men will be of good will.

Spiritual Unity will reign then.

Pages 8 and 9 of International Times, No. 10

This article was originally published in the French Jazz Magazine (No. 125, December, 1965), which is available here.

Back to Articles main menu

*

Coda (May 1967, p. 2-5) - Canada

[also available as a .pdf download]

albert ayler on record

Free Spiritual Music - Part 1

by Stu Broomer

Let us begin with a few statements that will suggest and clarify the possibilities, usefulness and existence of what has been called by Albert Ayler “free spiritual music”, or, as I would have it, freely spiritual music, that is, a music that does nothing to prohibit its entry into the realm of the spirit, for want of a more appropriate term within the confines of the English language.

If one blows into a saxophone, he may at first find it difficult to produce a sound. When this is achieved, a combining of primary technique (that is, producing a sound, arbitrarily altered) with physical energy will produce sounds of wide timbral and pitch variety, dizziness, and headaches. If this form of practice is continued for a long period of time, without imposing consciousness on the gradual cataloging of mechanical properties, a music will eventually form that incorporates only infinitely variable essentials, humanity, which is indeterminate, and musical instruments, all rich in unexplored possibilities.

The inadequacy of modern bio-chemistry, the nature of world religions, the total originality of the musics of Albert Ayler’s “imitators” suggest that we may all be within the range of the infinite. The continuing efforts of the U. S. government within the vague confines of the known universe suggest that man’s capacity for self-expression is expanding daily, and that this may conflict with basic energizing sources.

The natural order of any improvised music diminishes as structural material increases. The revolution that took place in jazz around 1960 has given music a possibility for a state of permanent change, a possibility of becoming simply god- inhabited.

The musics of Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, Sunny Murray, and Albert Ayler, taken together, sufficiently alter the traditions and conventions of black American music that a post-jazz expression becomes available to us. Through a rapid elimination of the historical and geographical aspects of style, Ayler has evolved from the working methods of Taylor and Coleman a music of universal implications that appears to be the last link in the transition from jazz, a music of closed cultural references, to a freely spiritual music that is of equal relevance to all who are exposed to it.

Ayler’s first recording to receive distribution (an earlier record made in Sweden in 1962 with Swedish musicians is evidently impossible to find) was recorded in Denmark in 1963 with accompaniment provided by a trio of conventional jazz musicians. The choice of compositions, so unimaginative that it could have been used ten years ago by Miles Davis, include Summertime, On Green Dolphin Street, Bye Bye Blackbird, and Billie’s Bounce, surely reflecting more on the repertoire of European musicians of an extremely dated hipness than on Ayler’s. Albert Ayler has said of bop: “For me, it was like humming along with Mitch Miller. It was too simple. I’m an artist. I’ve lived more than I can express in bop terms. Why should I hold back the feeling of my life, of being raised in the Ghetto of America?” On Billie’s Bounce, a blues written by Charlie Parker, Ayler’s music is completely removed from the conventional sense of continuity that one would expect. He plays a moving commentary on the senseless nature of the rhythm section; his mood is one of amused tenderness, that of a father whose knowledge is greater. On Summertime Ayler’s expressive powers are fully evident, and his statement about boys is illuminated. It is obvious here that musics of artifice have little relevance to musics of content, Ayler’s music having nothing of essential value in common with what bebop had become by 1963. This is the only recording that indicates Ayler’s years of apprenticeship in jazz, an education of increasing irrelevance as his music grew. The only attempt here at a freely collective music is C. T., presumably named for Cecil Taylor, with whom Ayler had been playing in Scandinavia, and it is a failure because of the accompanist’s failure to comprehend liberated motion. Ayler successfully parodies the bassist’s approximation of Spanish music, mocking such artificial considerations and manages to incorporate scraps of folk melodies that later assumed an essential role in his organizational procedures.

Ayler’s next opportunity to record came a year later in New York for the same European label and circumstances were much more favourable. With musicians experienced in the new idiom, the directions of Ayler’s music are much more apparent; the accompanists were capable of providing the wide frame of reference that the music demanded. Though a second horn is present it is not used in pre-determined ensembles, permitting the fluidly ornamental thematic statements to be made with complete ease. With a proper sense of motion established, the fast music makes its superiority evident in its ability to lead us to other planes, as heard here on “Holy Holy”, a composition that uses a single very fast figure to build momentum. “Witches And Devils” is in the mold of the funeral dirges played by New Orleans marching bands. Ayler says, “that the truth is marching in, as it once marched back in New Orleans.” This performance specifically recalls the Eureka Brass Band’s recording of “Eternity”.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

On this recording Ayler is still involved in relatively traditional methods of improvisation, playing solos of conservative structure, logically evolving from thematic variation methods common in jazz since its inception. Though the materials are more unusual, indicating a fundamental disregard for the value of any specified pitches of European convention, the uses Ayler makes of them are actually more conservative than those of Eric Dolphy.

Already it is evident that Ayler’s music has two fundamental tempos, extremely fast and extremely slow, though occasionally the senses of them overlap at this point. The slow performances, particularly the most successful one that Ayler has recorded, Witches And Devils, have an internal, “sensed”, pace that is very fast. While about the fast material, there is ultimately a sense of increasing coolness. Zen Buddhist priests explain a similar contrast in their chanting by pointing out that the faster you chant the more you forget what you are not supposed to have on your mind, while the slower you chant the more you must concentrate on what you are doing, or you will forget the next word.

At this point Ayler had become a voice of sufficient strength in the New York underground to have played a concert with Cecil Taylor and established members of the jazz avant-garde were being drawn to his music. When I first heard Ayler’s recordings with Gary Peacock and Don Cherry, I was favourably impressed by their collective work, but having heard earlier and later recordings of Ayler with musicians from his own Cleveland milieu I now regard the record with Cherry as the lowest point in Ayler’s recording career, excepting of course the initial album of bebop material. Ayler’s first recording to be issued in America, Spiritual Unity, with bassist Peacock and percussionist Sunny Murray, is still Ayler’s greatest achievement on record as an improvisational musician, his greatest contribution to new saxophone music. On it he displays brilliantly, the expressive reservoir of the instrument, easily surpassing the earlier music of John Coltrane, and demonstrating the spiritual energies required of a new musician. He extends the basic ideals of the traditional jazz improvisational mode as far as they can be stretched, in an effort to reach new planes of consciousness.

His recordings from this period in the company of other horn players are much less successful, having abandoned the comparatively delicate interplay of “Spirits”. Rather than destroying the self, “New York Eye And Ear Control”, and “Ghosts” serve to rebuild it. At both sessions, Ayler’s music was confronted by players lacking a conception of the fundamental necessity of energy, an element that gained in importance through the work of Cecil Taylor, then took precedence over European thought in the evolving musics of Murray and Ayler. “New York” included Ayler, Murray, Peacock, alto saxophonist John Tchicai, trombonist Roswell Rudd, and cornetist Don Cherry, and, apart from Murray and Ayler, all had considerable experience in a music that depended for its effectiveness on a cautious responsiveness to individual nuances, a method of collective improvisation employed by the New York Art Quartet, the Jimmy Giuffre Three, and the Sonny Rollins band with Don Cherry. The band’s power is diminished by a variety of conflicts in which the musicians individually or collectively attempt to impose their wills on the group music. Cherry, Rudd, Tchicai, and Peacock are all decidedly note-oriented which conflicts with Ayler’s sound-orientation, that is, his fostering of a pure organic music. (Ayler has said that you have to really play your instrument to escape from notes to sounds, and I would add that once a musician has involved himself in sound, thinking in terms of notes, “thinking” becomes absurd.)

“Ghosts” was recorded during a brief tour of Europe with Cherry, Peacock and Murray and here the clarity of the sound quality and the comparative simplicity make this an even more disasterous occasion. Cherry and Peacock play almost totally artificial music, their effect being melodramatic as they attempt to emphasize Ayler’s grace, simplifying at every opportunity the natural complexity of the music. It is also the only recording of an Ayler band in which unisons have been attempted on his more ornate compositions, the sense of which is destroyed in the process. The method of improvising employed here by Cherry is characterized by an innate “cuteness” while Peacock’s is highly manneristic.

The band that Ayler presented at Town Hall in May 1965 shows great progress in terms of a unified conception of group music. With Ayler at this concert were trumpeter Don Ayler, alto saxophonist Charles Tyler, bassist Lewis Worrell, and Murray, and unlike earlier co-workers their musics are energy-based, of an organic nature, moving towards a complete freedom from artificial considerations. Ayler’s structuring materials are more distinctly useful than those of the earlier records, less baroquely ornamental, and closer to the essential grace of song tradition available in the diatonic scale. With “Spiritual Bells” Ayler’s music enters more fully into the realm of the ritual. Individual statements emerge from intense repeated figures, the sense of which recalls mantras rather than riffs, which utilize the strongest intervals of Western music, natural overtones, the fourth, fifth, and octave, to get in touch with an hereditary unconscious, not to refresh the memory but to open the mind to the new stimuli being offered. Ayler’s own performance here seems less important than that of “Spiritual Unity”, but the music here is ultimately larger for its collectivity, its vision of a universe we must inevitably realize together. In the improvisations, particularly those of Tyler and Donald Ayler, there is a sense of a “musically” fragmented organic unity. The context of a phrase is no longer dependent upon the melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic values spontaneously established by any preceding unit of expression but rather achieves a sense of cohesion from the union of psyche, physiology and musical instrument.

“Holy Ghost”, from the same period, has cellist Joel Freedman in place of Charles Tyler, and though Freedman’s music is of considerably less significance than Tyler’s, the vastly superior recording quality gives the listener a better sense of the spiritual unity of the players. No amount of mere rehearsing enables musicians to play this kind of unison.

The only example of Ayler’s music released since “Bells” is “Spirits Rejoice” which similarly suffers from a very bad recording job. Spirits Rejoice was recorded in an empty concert hall and the element of ritual present in “Bells” and “Holy Ghost” is slightly diminished. The personnel is almost the same as that of “Bells” for most of the recording with Peacock and Henry Grimes replacing Lewis Worrell and providing a combination of energy and musical detail that was formerly impossible. “Spirits Rejoice” is music of an expanding love, like “Spiritual Bells” a carefully structured composition incorporating contrasting levels of expression. Much of it is pre-determined, incorporating folk-like melodies and the scope of it gradually expands to a series of intense solos.

While Ayler’s music has evolved from an approach to form and group organization that can be seen as a natural amplification of properties apparent in the early music of Ornette Coleman (that is, Coleman’s music up to and including 1961) to an expression of unique formal values, certain tendencies have remained. Ayler’s slow music, when not an aspect of a larger structural unit, has a tendency to degenerate into posturing self-indulgence (“Saints” on the “Spirits” album, “Mothers” on “Ghosts”, “Angels” on “Spirits Rejoice”) that is I think a result of its source. Ayler is evidently striving in his slow music to invest with substance the diatonic American ballad tradition without altering its essential qualities, and to transform sentimentality into reality, thus encountering problems not confronting his significant contemporaries who borrow freely from other cultural sources in their slow music.

Generally, Ayler's formal materials contrast sharply with those of his contemporaries. He seldom relinquishes the major scale, using it to communicate levels of joy supposedly of another time. His approach to rhythm too, is unusual, and perhaps a reflection of Sunny Murray’s drumming. Many of Ayler’s thematic statements are played in a relaxed rubato manner that, however, in no way detracts from the ultimate expressive precision of his music but that further contributes to the impression of a multi-faceted peace that he is trying to convey.

When Ayler’s compositions deviate from their diatonic roots, they do not move towards chromaticism but towards modality. “Holy Spirits”, a highly evocative dirge is written in the phrygean mode. “Spirits” employs the two whole tone scales which would normally have the potential to destroy diatonic references, establishing a uniformity of reference to each of the twelve tones of the European tonal system but in his ordering of the two scales Ayler chooses to relate the second scale to the first by beginning its statement on the dominant tone of the diatonic scale based on the immediately preceding emphasized tone, thereby arresting the potential harmonic breadth of the whole tone scale’s natural implication and leaving as reference the familiar diatonic scale.

Apart from the rare instances in which pre-determined materials clarify and amplify realization (“Spiritual Bells”, “Spirits Rejoice”) Ayler’s music is most successful when the compositional nature is purely energizing, without imposing specific materials on the music (“Holy, Holy”, “Holy Ghost”, “The Prophet” on “Spirits Rejoice”, “The Wizard” on “Spiritual Unity”).

Notes On Recordings

My Name Is Albert Ayler, the least essential recording of his music, is also the only one to have been released on a major American label, omitting a spoken introduction that is heard on European releases. It was originally issued as Debut 140 in Denmark, is available in Europe as Fontana 688 603 ZL, and in America on Fantasy 6014. It’s value is primarily historical, if that is any value at all, but, if necessary, it can instruct.

“Spirits” is the album title of a recording made in New York in February 1964 for the European market. It has been released in Denmark as Debut 148, in England as Transatlantic 130 and as Fontana 688 608 ZL. It includes “Witches And Devils” and “Holy, Holy” and has, in addition to the best recorded sound of any Ayler recording, trumpeter Norman Howard’s sole appearance on record with Ayler.

“Ghosts” was the last recording made by Ayler for a European label and was made during a visit to Denmark with Cherry, Peacock, and Murray in 1964 after the initial recordings for ESP. Performances of note are “Holy Spirit” and “Children”. It has been released as Danish Debut 144 and as Fontana 688 606 ZL.

None of the European recordings of importance are readily available in North America, nor have they been released in stereo. The ESP releases, Spiritual Unity 1002 with Peacock and Murray; Bells 1010, from the Town Hall concert; Spirits Rejoice 1020, suffer from poor distribution, short duration, and terrible recording quality. The failure of major recording companies to show any interest in new music has resulted in numerous unrepresentative recordings being released. The best single Ayler performance on record is “Holy Ghost” on an Impulse sampler A-90 aided by comparatively excellent recording that allows the listener to appreciate the important roles played by the accompanying musicians.

“New York Eye And Ear Control”, ESP 1016, is made up from material recorded for Michael Snow’s film of the same name. It was recorded a week after Spiritual Unity and was intended as an all star unit composed of musicians from the new wave. At the time of selection Snow did not know that Peacock and Murray were Ayler’s regular accompanists.