|

Music Is The Healing Force Of The Universe The Inconsistency of |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

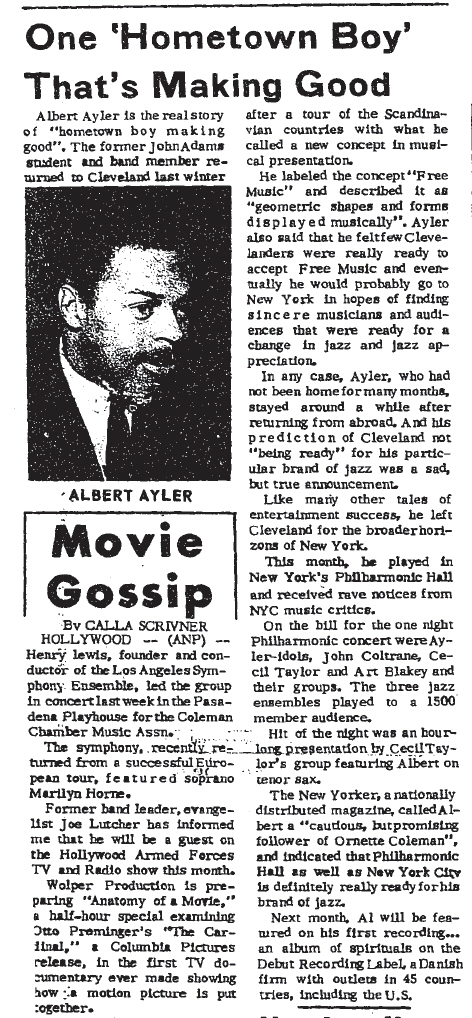

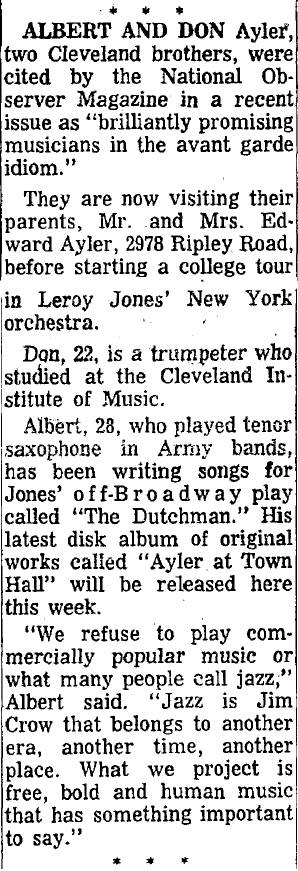

“Free Music” ... Discorded Chaos? Cleveland Call & Post, 9 February, 1963 - USA One ‘Hometown Boy’ That’s Making Good Cleveland Call & Post, 1 February, 1964 - USA Albert Ayler vier dagen hier Het Vrije Volk, 5 November, 1964 - Netherlands A recording session with Albert Ayler and Don Cherry Vrij Nederland, 5 December, 1964 - Netherlands The Moody Men Who Play the New Music by Robert Ostermann National Observer, 7 June, 1965 - USA Albert and Don Ayler by Glenn C. Pullen Cleveland Plain Dealer, 13 July, 1965, p. 19 - USA Albert Ayler Le Magicien by François Postif Jazz Hot, No. 213, October 1965 - France Autumn In New York II (extract) by Guy Kopelowicz Jazz Hot, No. 215, December 1965, p. 40 - France Untitled by Albert Ayler Jazz Magazine, No. 125, December 1965, p. 41 - France Spiritual Unity by Albert Ayler Guerrilla, Vol. 1, No. 1, January 1967, p. 24 - USA (Detroit). An English translation of the item above. *

Cleveland Call & Post (9 February, 1963) - USA “Free Music” ... Discorded Chaos? |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

“People are going to the moon. It’s time for music to change too,” is the introduction and explanation of “Free Music, as interpreted by Albert Ayler, recently returned from a musical tour of the Scandinavian countries, who brought with him a totally new departure in jazz music to the Cleveland area. --!!-- An impressive list of notables who have accepted this new, adventurous departure Christened by Ornette Coleman, largely self-taught alto saxophonist, would include Sonny Rollins, John Coltrane and Cecil Taylor.

*

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

*

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

*

Vrij Nederland (5 December, 1964) - Netherlands [A .pdf of the original article is available here. The following translation was provided by Kees Hazevoet.]

A recording session with Albert Ayler and Don Cherry by Bert Vuijsje It is Monday, November 9, 8 pm at VARA Studio 5. Tenorist Albert Ayler, trumpeter Don Cherry, bassist Gary Peacock and drummer Sonny Murray are going to record for Jazz Magazine i. The others present – the editorial team of Jazz Magazine, impresario Paul Karting and a handful of Dutch jazz musicians – anxiously await what is to come. Last weekend Peacock suffered three bouts of stomach trouble and on Sunday afternoon Murray demanded an extra 50 guilders for the performance in Alkmaar. Karting refused and the group therefore played without a drummer in ‘Extase’ at the Bergerweg. Tonight the prospects are better: at 7.15 pm the whole group was already present in the studio to install the instruments and do some warming up. The music of this quartet does away radically with a number of traditional conventions that most avantgardists have only reluctantly undermined so far. The intimate relation between theme and improvisation that they maintain is emotional, the mood of the theme influences what is to follow. There still is a tempo, even though it often changes, but there is no division into bars anymore. The drummer divides the time and that is all; the usual partition in more and less accentuated beats has been abandoned. The bassist does not have to play or suggest four to the bar and neither is he restricted to the harmonies associated (either explicit or implicit) with the tune’s theme. Hence, the soloists have a heretofore unknown freedom, which – other than one may think – does not make their task easier. When the theme has been stated they are confronted with a total blank that has to be filled purely with their own ideas. The comfortably and routinely ‘running the changes’ (playing the tune’s harmonies) is not possible anymore and everything has to come from their own inspiration. At 8.10 pm the recording engineer says he is ready to go. A short piece is played to check the balance. Then the group starts off with ‘Angels’, one of the five Ayler originals that will be played. Don Cherry hardly moves, only during high passages he sometimes bends his knees. During his career he has often been the modest and lyrical counterweight of a dominant leader (Ornette Coleman, Sonny Rollins). With this quartet he again seems to take up that role. He alternates between fast and nervous runs of notes and quiet and strongly melodic lines. Ayler’s violent movements are reminiscent of Johnny Griffin. Like Griffin he gives the impression of permanent and complete involvement. He employs an unusually strong and slow vibrato that, paradoxically, reminds one of the first attempts – some forty years ago – to play jazz on a saxophone. Completely contemporary are Ayler’s tonal experiments, in which he is clearly influenced by Coltrane and, especially, Rollins. Peacock’s amazing speed, the effortless way in which he uses double stops and the sheer unbelievable certainty with which he plays even the highest notes, demonstrate that the technical advances in playing the bass in the US during the past few years have proceeded even quicker than was suspected in Europe. He is an exceptionally gifted accompanist; without imposing his ideas on the soloist, Peacock supports him with inventive background figures of great beauty. Sonny Murray constantly makes strong movements with the mouth and accompanies himself with a piercing buzz that becomes irritating after a while. After the second piece, ‘C.A.C.’, the result of this first set is played back and listened to. Don Cherry lights a cigarette and sits down on one of the covered hammond organs. Ayler restlessly walks back and forth. Peacock leans on a piano and stares out of the window. Murray listens attentively with his head bent. The music coming from the loudspeakers is much better balanced than the live performances that we heard during the past days (the term ‘studio quality’, often used in advertisements for cable radio ii, proves to be rather misleading). It now becomes even clearer how sublimely Peacock accompanies; with a much reduced volume, Murray’s obtrusive playing becomes more bearable. The playback ends with a long and resonating bass note. Ayler descends from the control room. Cherry, who appears to be an enthusiastic amateur pianist, plays Thelonious Monk’s ‘Light Blue’ on the piano. Murray walks back to the drums, making some jerky dance steps along the way. Peacock again installs his bass into a custom made little plank with slots. As more music has to be recorded, Cherry swaps the piano for his pocket-trumpet. iii The third number is ‘Ghosts’, a theme that could easily become a nursery rhyme. Murray soon loses one of his sticks, which Ayler patiently returns to him. Herman Schoonderwalt and Ruud Jacobs iv are listening with some amusement to Ayler’s musical force. Bassist Arend Nijenhuis v listens seriously and apparently is completely absorbed. When the number is finished, only Nijenhuis applauds, causing Don Cherry to look over his shoulder quite suspiciously. During the next number, Don Cherry’s ‘Infant Happiness’, Sonny Murray loses a stick four times vi. At 8.55 pm another break is taken. Ayler goes upstairs [to the control room]. Cherry plays some more Monk piano, now with Murray in the upperhand. There is less attention for the recorded music than the first time. Paul Karting tells me that Cherry, after the concert in Rotterdam on Saturday, played piano for two hours, with local musicians on bass and drums. Murray starts packing his borrowed drum set vii, but two more numbers are still to be recorded, so he assembles it once again. Don Cherry plays, accompanied by Peacock, a slow and fluent melody. His technique has improved considerably since he started with Ornette Coleman. The last set is ended with an as yet untitled Ayler original. Cherry’s solo in this number shows to be largely a repeat of what he just played during the intermission. Apparently, even in free jazz an original improvisation slowly becomes a standard solo. At 9.35 pm, the 40 minutes of music that are needed are on tape. Peacock and Murray are really packing now. Cherry puts on his grass-green woolly hat and takes out a little bamboo flute. Ayler wears a light yellow Russian hat. Jazz Magazine editor Kees Schoonenberg tells that during the session Paul Godwin entered the control room and cried out: ‘That bass is so totally in tune!’, and went to call the other members of the Hollands Strijkkwartet [Netherlands’ String Quartet]. The musicians still have to be paid, which gives rise to some confusion as to whether or not Ayler has filled in an allocation sheet. Tomorrow the members of the quartet will each go their own way. Like in the US, there is very little work for these kinds of groups in Europe. Murray is going to make a record in Copenhagen, Cherry travels to London and Peacock is going to visit a doctor in Brussels. Only Ayler does not have definite plans yet. There is extensive farewell saying. Ayler travels back to Amsterdam with us. On the way he tells with some pride that Coltrane played his last LP ‘Spirits’ for the full 40 minutes. Ayler does not seem to like Mingus at all: “Much too commercial. I never understood what made Dolphy play with him. Miles, Rollins, Coltrane, they know who’s playing”. Although two Danes played on his first record, he now could not work with European musicians anymore. He tells that he lived in Harlem for six months (‘do you know the word tension?’), and that most musicians did not have the guts to visit him there. “Only Ornette sometimes passed by; he had a girl there”. His composition ‘Ghosts’ originated during that time. Suddenly he asks what kind of records I have. My answer (a lot of Parker, some Mingus and Coltrane) seems to disappoint him. Apparently, Ayler does not belong to those musicians that have much interest in older (nowadays a rather relative adjective) jazz forms. At 10.45 pm we drop Ayler at his hotel at the Geldersekade. He is going to sleep some and perhaps later visit the Sheherazade viii. Around 11.30 pm it proves to be depressingly empty there and we return home in a somewhat disenchanted mood. _____ i During the 1960s, Jazz Magazine was a weekly program on VARA-radio. [Originally published in Vrij Nederland of December 5, 1964 *

[The following article was included as an insert with the original pressings of Bells - which explains why the ESP catalogue is added at the end. A scan of the original insert is available here.]

National Observer (7 June, 1965) - USA They Don’t Call It Jazz The Moody Men Who Play the New Music JAZZ has always occupied the position of a renegade, a maverick, in the U.S. cultural life. It has never won complete acceptance, despite the distinction occasionally brought to it by the rare genius of a Duke Ellington. And its forays beyond the musical barricades into classical fields have been so sporadic as to be almost accidental. The Disturbing Sounds The music they’re playing is uncomfortable to the ears of most jazz buffs, even those who have grown up with jazz from Dixieland, Louis Armstrong, and Lester Young to such innovators of the last 15 years as Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, and John Coltrane. It disturbs them. It doesn’t sound like jazz. To some it doesn’t even sound like music. Improvising the Tune But this contemporary music, currently bearing the atrocious label “The New Thing,” pushes improvisational playing toward its final point. There is no tune; the performer improvises from scratch. More and more group improvisation can be heard taking priority over the solo musician and his performance. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

—Charles H. Stewart Gary Peacock: ‘Learning to listen |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

—Charles H. Stewart Cecil Taylor: ‘I try to imitate on the piano the leaps . . . a dancer makes.’ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Conflict With Teachers Mr. Taylor was born in 1933 and started studying piano at 6. His mother played both piano and violin and was also a dancer. He first studied at the New York College of Music, later switching to the New England Conservatory in Boston. There he found his views were often at odds with those of his mentors. “There were certain Bartok scores,” he recalls, “in which I saw things no teacher told me anything about.” |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

If you attended the recent Town Hall Concert in New York performed by a group under Albert Ayler you might find it difficult to contest that assertion. For 25 minutes no one in the audience moved. One listener reports he had the impression of time stopping, and that everyone seemed to come to at the conclusion of the music. “As if,” he says, “the audience were being pulled up out of the deepest reflective mood.” |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

—Bob Greene Albert Ayler: ‘You have to really play your instrument to escape from notes to sounds.’ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Byron Allen, a 25-year-old alto sax player from Omaha, Neb., is in complete agreement. He protests against putting labels on music. “There’s music and there are human beings,” he says. “That’s all. I’m not playing jazz. My mother didn’t bring a jazzman into the world; she brought a human being. That’s what I’m playing—human music.” |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

At the moment of recording the selections on his Trio record, Mr. Allen was very conscious of the fact that he’d just learned his wife was pregnant. “Her being pregnant, that’s what I was thinking about. I wanted to put happy music on the record. I gave them a sound pattern to spring off of and we worked from there.” |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Mr. Graves is 23 and has four children. He teaches music at the Black Arts Repertory Theater founded and operated in Harlem by the poet and playwright LeRoi Jones. He doesn’t have many working dates as a musician, and his family’s finances flash up and down unexpectedly. “That’s the music, too,” he says, “full of surprises, perhaps a little uneven and rough.” The Message in Music In his view there’s nothing radically new in this music. He points out that all music has a nonrepresentational, non- sensory content, a message. This is in music no matter how familiar and conventional. But music also has a personality, and he says the message doesn’t get through to listeners if they stay at the level of the music’s personality. He guesses most people aren’t hearing all of the music they claim they like and know. “Learning to listen is a basic problem,” he says. “Everyone has it.” —ROBERT OSTERMANN Reprinted from National Observer, June 7, 1965 ______________________________

HERE IS THE ESP CATALOGUE OF NEW MUSIC. ALBERT AYLER TRIO: ESP-1002 (monaural only) (with Gary Peacock & Sunny Murray) PHARAOH SANDERS QUINTET: ESP-1003 (with Jane Getz, Stan Foster, Marvin Pattillo, William Bennett) NEW YORK ART QUARTET: ESP-1004 (with LeRoi Jones, Milford Graves, Lewis Worrell, Roswell Rudd, John Tchicai) BYRON ALLEN TRIO: ESP-1005 (with Maceo Gilchrist, Ted Robinson) GIUSEPPI LOGAN QUARTET: ESP-1007 (with Milford Graves, Don Pullen, Eddie Gomez) PAUL BLEY QUINTET: ESP-1008 (with Marshall Allen, Milford Graves, Dewey Johnson, Eddie Gomez) BOB JAMES TRIO: ESP-1009 (with Barre Phillips, Bob Pozar) ALBERT AYLER AT TOWN HALL (BELLS): ESP-1010 (with Don Ayler, Charles Tyler, Sunny Murray, Lewis Worrell) RAN BLAKE PIANO SOLOS (VANGUARD): ESP-101l (monaural only) LOWELL DAVIDSON TRIO: ESP-1012 (with Milford Graves and Gary Peacock) GIUSEPPI LOGAN AT TOWN HALL: ESP-1013 (with Milford Graves, Don Pullen, Reggie Johnson) SUN RA, THE HELIOCENTRIC WORLDS OF VOL. 1 ESP-1014 LIST PRICE for both monaural and stereo is $4.98 You can get on our mailing list for future release information by sending your name and address to: FORTHCOMING RELEASES: ESP-1015.MILFORD GRAVES PERCUSSION ENSEMBLE ESP-1016.PAUL BLEY TRIO: (with Steve Swallow and Barry Altshul) ESP-1017.THE HELIOCENTRIC WORLDS OF SUN RA Vol. 2 THE GIUSEPPI LOGAN CHAMBER ENSEMBLE IN CONCERT. ESP-1018

*

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

*

Jazz Hot (No. 213, October 1965, pp. 20-22) - France albert ayler le magicien |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

La poursuite d’une nouvelle esthétique dans le jazz depuis la disparition de Parker a été le fait des saxophonistes. Il suffira de citer les noms d’Ornette Coleman, de John Coltrane, d’Eric Dolphy et d’Archie Shepp. Le saxophone est, de tous les instruments, le plus malléable, le moins « carré », celui qui permet les fantaisies que nous résumerons sous le nom de « recherches ». C’est, avec le violon, un instrument très proche de la voix humaine, donc, selon les musiciens de la nouvelle vague, le plus « humain »: d’une part par le côté plaintif, souvent geignard, qui fait grincer les dents des détracteurs, et, d’autre part, par la volubilité. Albert Ayler, comme on le verra par la suite, est passé maitre dans l’art de malaxer le son. C’est l’un des musiciens les plus connus (ou les moins méconnus) de cette école post-coltranienne désignée sous le vocable de « new thing ». Comme Archie Shepp, un certain nombre de disques lui ont valu une gloire fragile. C’est, lui aussi, un saxophoniste ténor. Il est né le 13 juillet 1936 à Cleveland, dans l’Ohio. Bien des musiciens de la « new thing » abordent aujourd’hui la trentaine. A dix ans, Albert joue de l’alto aux enterrements locaux, dans l’orchestre où son père tient le ténor. En 1952, après quelques formations de Cleveland, il se joint pour quatre mois à l’orchestre de rhythm and blues de l’harmoniciste Little Walter Jacobs. En 1956, il passe définitivement au saxophone ténor, et, depuis son arrivée à New York, en 1962, se présente soit avec sa formation, soit avec celle de Cecil Taylor (comme Archie Shepp; et Archie ajoute: « Bien obligé. D’ailleurs qui d’autre que Cecil voudrait m’engager? »). A l’automne 1962, Albert Ayler arrive en Scandinavie avec Cecil, enregistre un disque à Stockholm pour une marque confidentielle (avec des musiciens suédois) puis passe au Café Montmartre de Copenhague. Coltrane, poursuivant une tournée européenne par le Danemark, vient l’écouter et déclare qu’il a toujours souhaité jouer comme lui, ce qui est un beau compliment. Albert retourne à New York et se produit avec Cecil Taylor dans un concert fort attendu, au Philharmonic Hall, Lincoln Center de New York, le 31 décembre 1963. A la suite de ce concert, LeRoi Jones s’enthousiasme et n’hésite pas à écrire que tout saxophoniste ténor ferait bien de sa méfier, « car Albert Ayler swingue comme ça n’est pas permis ». Et, dans son compte rendu pour Down Beat, il compare la sonorité d’Albert Ayler à celle d’une corne de brume. D’ailleurs, à Cleveland, les camarades musiciens d’Albert Ayler, bien avant sa venue à New York, l’avaient déjà surnommé « Bicycle horn » (corne de bicyclette). Pour en terminer rapidement avec ce que nous savons de la vie d’Albert Ayler, disons brièvement qu’en juin 1964, il se produit de nouveau à New York sous son propre nom, avec le bassiste Gary Peacock et le batteur Sonny Murray. Il s’adjoint Don Cherry pour une tournée européenne, à la suite d’un engagement au Café Montmartre pour septembre 1964: le quartette visitera ensuite la Suède et la Hollande (Amsterdam, Rotterdam et Alkamar, où Sonny Murray refusa de jouer). Puis, éparpillement général: Ayler et Murray retournent aux Etats-Unis, Gary Peacock se remet de maladie en Belgique, tandis que Don Cherry reste en Europe pour plusieurs mois. Passons maintenant aux disques. Nous n’avons pu nous procurer le premier disque d’Albert Ayler, enregistré en octobre 1962 avec des musiciens suédois. Dans le second disque paru sous son nom (My name is Albert Ayler, Debut 140), il est entouré de musiciens danois, si l’on excepte le batteur qui, lui, est américain: le très jeune bassiste Niels- Henning Orsted Pedersen, auquel on est en droit de préférer l’un de nos bassistes parisiens, et Niels Bronsted, au toucher très powellien. Après une introduction parlée qui ne présente pas grand intérêt, Albert Ayler, avec une sonorité très proche de celle du biniou, attaque au saxophone soprano « Bye bye blackbirds » en longues phrases artistement ciselées. Malheureusement, la rythmique, trop « conventionnelle », trop « pulsative », loin d’aider à l’épanouissement des plaisantes arabesques d’Albert Ayler, semble le retenir sur terre. Ayler, dans ce morceau, joue tout en douceur: pas d’attaques nerveuses, pas de rauques envolées. On a au contraire l’impression qu’il s’installe dans la mélodie et laisse glisser au fil des idées les volutes de sa sensibilité. Son phrasé est très fluide et contraste étrangement avec sa sonorité légèrement acide; la ligne mélodique est hardie, certes, mais pas heurtée. A la fin du morceau, ses interrogations sont suffisamment parlantes pour exiger une réponse que ses interlocuteurs sont bien incapables de lui fournir. Puis, il interprète le blues, un blues de Charlie Parker, « Billie’s Blues ». Pendant tout l’exposé, il reste collé à la mélodie, puis, sans forcer, s’anime et découpe avec son ténor de fragiles dentelures. C’est du travail bien fait, mais, là encore, nous restons persuadés que ses accompagnateurs ne lui ont pas permis de s’envoler. Eric Wiedeman dit, sans doute par euphémisme, que le blues ne semble pas être le matériau idéal pour Albert Ayler, ce qui semble étonnant. Le meilleur moment de ce microsillon tient dans le traitement qu’Albert Ayler donne au célèbre thème de Gershwin, « Summertime ». C’est une longue supplication interprétée dans un soupir, d’une très grande beauté, toujours très proche du thème et cependant plein d’abandon. C’est là le côté lyrique d’Albert Ayler qui, par moments, devient peut-être un peu geignard, mais qui reste tout le temps extrêmement émouvant. La sonorité n’en est plus une, tant elle se plait aux confins de l’immatériel. Cette interprétation rend ce disque important: Albert Ayler y place toute sa tendresse, caresse amoureusement la mélodie et lui donne progressivement vie, tel un potier façonnant l’argile. La morceau suivant, « On Green Dolphin street », est nettement moins bon, mais permet d’entrevoir les possibilités d’Ayler dans ses improvisations « free form ». Il adopte là une sonorité que nous qualifierons de « multiple » (1). En effet, il laisse percer de temps à autres plusieurs notes ébauchées sur son ténor, et cette note qui en résulte, parfois double, parfois triple, provoque chez l’auditeur une certaine gêne voluptueuse. Cette façon de faire sonner plusieurs notes en même temps, par son aspect sauvage, donne au phrasé d’Albert Ayler une couleur très crue, personnelle, qui n’est pas pour déplaire. Puis vient « C.T. » (ces initiales sont certainement celles de Cecil Taylor), paradoxalement joué sans piano. Albert Ayler commence étrangement par quelques sons rauquas bien sentis, aboiements pour certains (nous aurions volontiers parlé de miaulements de jeunes chats dans « Bye bye blackbirds ») puis se lance dans un solo rageur très expéditif. L’absence de piano semble lui permettre beaucoup plus d’audace et ses partenaires restants se montrent sous un jour meilleur. Nous n’avons pas écouté le premier disque d’Albert Ayler avec des musiciens suédois. Dans ce second enregistrement avec des musiciens danois, Albert Ayler s’est senti freiné par la section rythmique qui lui apportait une pulsation trop métronomique. Dans ce genre de musique qui s’apparente à la « free form », il faut au contraire des accompagnateurs très souples qui s’adaptent immédiatement au phrasé du soliste au lieu de le conditionner. Trois autres disques d’Albert Ayler bénéficient heureusement de la participation de Sonny Murray à la batterie; celui-ci propose un exemple de ce qu’il convient de faire avec des musiciens comme Ayler. De retour aux Etats-Unis, et à partir de son troisième disque, Albert donne à sa musique une signification très particulière; il plonge dans le spiritisme et la magie. On voit alors apparaitre dans les titres des diables, des sorcières, des magiciens, des esprits et des fantômes. Inutile d’ajouter que sa sonorité deviendra encore plus diaphane, plus spectrale, plus immatérielle. Ce troisième disque (Spirits, Debut 146) est entièrement l’oeuvre d’Albert Ayler. Il a choisi les thèmes — les siens — et les musiciens qui l’entourent: un de ses amis de Cleveland, le trompettiste Norman Howard, très jeune (c’était sa première séance d’enregistrement), et deux amis de l’ensemble de Cecil Taylor, Henry Grimes et Sonny Murray. Enfin, un second bassiste, Earle Henderson. La premier morceau, intitulé « Spirits » (ce qui n’est pas pour nous étonner), est littéralement arraché par Norman Howard et Albert Ayler, tour à tour mordants et frétillants sur un tempo casse-cou. Norman Howard tire admirablement son épingle du jeu, grâce à ce phrasé-mitraillette si cher à Cecil Taylor. lnutile de faire tourner les tables pour prédire à ce brillant trompette un avenir à la hauteur de ses possibilités. Quant à Henry Grimes, par petites touches bien senties, par une sorte de crépitement joyeux et par ses volubiles ponctuations, il ajoute, si besoin était, à la complexité du morceau. Nous sommes fort loin, ici, des hésitations maladroites du disque précédent. Le morceau commence et se termine par une lointaine évocation de ce qui deviendra le thème de bataille de la « new thing », « Ghosts ». « Witches and devils » débute par une longue incantation maladive que Norman Howard distille comme s’il allait rendre son dernier soupir; et c’est peut-être cela qui nous attire dans l’exposé de ce thème. Morceau lent s’il en est, joué encore plus lentement, et rendu encore plus ralenti par cette façon unique qu’a Norman Howard de souffler presque en s’excusant. Rien de grandiose dans cette face, rien de grandiloquent, simplement du pathétique. Albert Ayler, un peu plus « coriace », prend la suite de cette mélopée, dont le déroulement thématique est poussé au paroxysme. Musique crépusculaire, bien située par son titre, pleine de bruits étranges que poursuivent sur leurs instruments respectifs les deux bassistes de la session. Musique obessionnelle, affolantes recherches qui évoquent, par certains côtés, celles de Sun Ra (2). « Holy holy » est un long solo d’Albert Ayler, avec sa sonorité grinçante et son air bon enfant, irritant, mais tellement passionnant aussi. Ce genre de musique doit être abordé avec des oreilles neuves. Dans ce morceau plus que dans les précédents. Albert Ayler surprend par ce côté « crin-crin » qui reste sa marque de fabrique et qui n’est pas nécessairement du goût de tout le monde. Au milieu de son solo, un rappel de « Ghosts » d’une fort bonne venue, juste avant Norman Howard qui fait défiler une impressionnante théorie de notes avec une sonorité d’une surprenante qualité. Le jeu de ce trompette cadre parfaitement avec les idées d’Albert Ayler dont il donne un habile prolongement. Le dernier morceau, « Saints », est de la même veine que « Witches and Devils »: il se déroule sur un tempo ralenti à l’extrême, avec Albert Ayler trendre et lyrique, Norman Howard, souffreteux, et Sonny Murray rare. Disque important, car il nous montre Albert Ayler chez lui, dans son univers, jouant pour la première fois ses propres thèmes avec sa propre formation. Si, comme tout le laisse supposer, cette révolution formelle impose aux batteurs une révision complète de leurs conceptions pour permettre aux solistes de s’exprimer comme ils l’entendent, alors Sonny Murray fait partie des nouveaux venus les plus intéressants. Le sens de la mesure dont il fait preuve tout au long de ce disque donne à Albert Ayler et à Norman Howard l’occasion de jouer comme ils l’entendent. Avec le disque suivant (Spiritual Unity, ESP 1002), enregistré quelques jours avant son départ pour l’Europe, l’année dernière, nous retrouvons avec plaisir Sonny Murray, auquel s’est joint le bassiste Gary Peacock. Le premier thème, « Ghosts », est, comme nous l’avons déjà dit, l’indicatif d’Albert Ayler, et selon un mot de Don Cherry, devrait devenir l’hymne national américain. Cet air aux harmonies un peu simplistes n’est pas sans beauté, sans majesté même. Albert Ayler l’interprète d’une façon délibérément acide, tandis que Gary Peacock assimile parfaitement le langage du groupe en donnant une réplique très détachée: Sonny Murray accompagne pendant tout le solo, très discrètement, sur ses cymbales. Puis, après un solo crépitant de Gary Peacock, très « parlant » dans le sens où l’entend Mingus, Ayler reprend le thème d’une façon tellement mélodique que l’on a peine à croire que c’est le même saxophoniste qui improvisait tout à l’heure. Second morceau, « The Wizard », qui, à mon sens, ne comporte pas de thème. On entre directement dans le vif du sujet, avec de courtes phrases maladivement jouées par Albert Ayler. Peu de beauté formelle dans cette face, simplement une progression rageuse que sert une sonorité rugueuse. Un peu « coeur mis à nu », et nous « marchons ». Normalement, cette série de notes rébarbatives, jouées sur un instrument qui semble pourri, devraient faire fuir; malgré tout, elles possèdent une attirance irrésistible — un peu comme une femme laide mais pleine de charme. Dans le morceau suivant, « Spirits » qu’Albert Ayler joue avec une aisance de bon aloi, on retrouve ce côté « chat écorché » et une virtuosité dans l’acide jamais atteinte. Albert Ayler interprète ce morceau avec beaucoup de vigueur et d’autorité, toujours accompagné par un Sonny Murray cymbalisant sans relâche et contrastant de façon saisissante avec Gary Peacock, égrenant sporadiquement des lignes chromatiques. Il règne dans ce morceau une atmospère de folie qui va crescendo, dominée par les notes ailées d’Albert Ayler. Au fur et à mesure du développement de son solo, Albert Ayler devient de plus en plus énervé, de plus en plus fiévreux, mais il reste toujours maitre de son phrasé et, surtout, de sa sonorité. Ayler, de son propre aveu, a longtemps limité ses improvisations aux changements d’harmonies pour se concentrer sur sa sonorité. Il utilise actuellement une anche en matière plastique dure, car, dit-il, il cassait trop souvent les anches en bois qu’on trouve dans le commerce. C’est peut-être cette anche qui donne à son instrument ce timbre difficile, à la fois grêle et ample, à la fois caressant et acide. Lorsqu’il joue en douceur, comme dans l’introduction de cette nouvelle version de « Ghosts », il flatte des lèvres la mélodie et devient extrêmement délicat. Nous avons déjà dit que le thème « Ghosts », presque spiritualisant, est construit sur des harmonies simples qui en font la beauté. Brodant sur cette mélodie, Albert Ayler devient presque « classique », puis soudain va frétiller dans les eaux troubles de sa sonorité « multiple ». Ce long solo, bourré d’idées propulsées d’une seule venue, contient les exemples les plus frappants de son jeu: courtes phrases intenses, rageuses, volubiles, vivaces et généreuses, Gary Peacock chatouille sa basse en un court solo, puis Albert Ayler repart, avec la même fougue, pour revenir, apaisé, au thème initial. Il est difficile de ne pas aimer ce disque qui présente de façon fort complète Albert Ayler sous son meilleur jour, tour à tour sensible, enjoué, pathétique, véhément, triste ou grandiose, toujours original. Sa facilité déconcertante à se séparer d’un thème et à improviser trouve dans ce recueil matière à développements, simplement parce qu’il joue seul, sans seconde voix, avec des musiciens qu’il connait bien. Il les emmènera pour sa tournée européenne de 1964, en y adjoignant le trompettiste Don Cherry, bien connu pour ses travaux avec Ornette Coleman. Nous retrouvons donc ces quatre musiciens dans un nouveau disque (Ghosts, Debut 144) (3) enregistré à Copenhague l’année dernière. Naturellement, les thèmes possèdent tous cette ambiance mystique un peu surnaturelle, mais la présence de Don Cherry, trompette qui complète les idées d’Albert Ayler, leur donne plus de variété et plus de poids. Tout d’abord, une fort courte (deux minutes) version de « Ghosts », sans solo. Simplement l’exposé du thème repris deux fois, très amplement, très majestueusement, comme s’il s’agissait d’un morceau d’église. « Ghosts » est un thème plaisant, qui se retient aisément. Le second morceau de ce recueil, « Children », est une suite de solos très calmes, avec ce côté lyrique et passionné si cher à Albert Ayler. Après un enchevêtrement de lignes mélodiques, Don Cherry dégage un solo tout en nuances et joliment venu, composé de notes très rapides, mais pas saccadées. Il convient d’admirer ici l’aisance d’un batteur comme Sonny Murray, qui s’ajuste au jeu de Don Cherry sans jamais le devancer; dans cette nouvelle façon de jouer, la rythmique n’est qu’une indication, sans plus, mais par son travail en douceur, elle maintient la cohésion de tout l’édifice. On ne « sent » jamais Sonny Murray, on le pressent, on sait qu’il est là, et il faut tendre l’oreille et prêter attention pour se rendre compte du magnifique support qu’il procure aux protagonistes de ces faces. Puis vient « Holy Spirit », un morceau lent qui contient sur la fin un très beau solo de contrebasse qui fait irrésistiblement penser à un Mingus moins ventru. Peacock fait « parler » sa contrebasse, doucement, avec tendresse, juste avant la reprise du thème à l’unisson. La seconde version de « Ghosts » est beaucoup plus longue que la précédente (sept minutes et demie). Outre des solos d’une facture très plaisante par Albert Ayler et Don, elle nous offre un curieux passage de contrebasse à l’archet; Gary Peacock effleure les cordes avec une sonorité exceptionnellement primitive pour se mettre dans l’esprit du morceau. Il nous rappelle ces fameuses « notes multiples » chères à Albert Ayler, dont nous parlions plus haut. « Vibrations » veut, selon Albert Ayler, évoquer la vitalité du peuple des rues de Harlem: morceau rapide, toute en notes arrachées, tout en violence. Puis, dans « Mothers » un étrange retour au calme lyrique: Albert Ayler met littéralement son coeur palpitant dans le creux de sa main et le regarde battre. Il y a dans cette face une beauté tragique, rappelant (surtout pendant le solo de Don Cherry) ces mélodies d’arène espagnole, jouées pendant la mise à mort, cependant que chacun retient son souffle. C’est très émouvant. Ces quatre disques, mis à la suite les uns des autres, ne donnent certes qu’un aperçu des possibilités d’Albert Ayler, mais nous pensons que cette analyse d’une partie de son oeuvre le présente sous un jour très favorable, très encourageant. Albert Ayler ne donne pas dans l’hermétisme, sa musique est sans prétention et possède tous les éléments qui peuvent la faire admettre par tous les amateurs de jazz. En effet, on trouvera difficilement trace de cahot ou de désordre dans ses lignes mélodiques, parfois très pures; aucun cabotinage, aucune manifestation ésotérique: ses conceptions sont saines, jamais ennuyeuses, et sa façon de les exprimer, bien que souvent tumultueuse, reste toujours dans le domaine de l’audible (4). Seule différence avec le jazz auquel notre oreille s’est habituée, il nous faut accepter l’étranger, le surnaturel, la fiction et abandonner toute idée préconçue. Albert Ayler le magicien, d’un coup de sa baguette, nous ouvre le rideau de ce théâtre enchanté où se poursuivent esprits et chimères. C’est cet univers ténébreux et sauvage qu’il s’efforce de restituer, ce domaine inconnu dont il semble revenir à regret. François POSTIF. __________ (1) Roland Kirk obtient un effet similaire en jouant sans anche. (2) Le musique du pianiste Sun Ra et de son « Arkestra », sur lequel nous préparons une étude, se réclame elle-aussi du supra-terrestre. Mais alors qu’Albert Ayler évolue dans les sphères de la magie noire, Sun Ra prétend recevoir des messages des autres planètes qu’il transpose en musique. La différence, c’est celle qui existe entre le « spectral » et le « spatial », et, musicalement parlant, le résultat est — il faut bien le dire — assez similaire, à celà près que Sun Ra utilise tout un orchestre. (3) «Ghosts » va être publié en France sous le label Fontana 688-606. (4) Contrairement à certains critiques, nous ne voyons pas l’avenir du jazz dans la difficulté. Pour redevenir populaire, donc pour survivre, le jazz doit atteindre un vaste public et en revenir aux saines conceptions de l’improvisation. Dans le cas d’Albert Ayler, cette improvisation est très libre. Les arrangements, s’ils existent, ne sont même plus un cadre, une limite à l’inspiration: au contraire, ils constituent un tremplin. Une improvisation complètement libre et par moment un peu foile, une improvisation qui va la bride sur le cou.

*

[The following extract from Guy Kopelowicz’s series of articles about New York’s avant-garde jazz scene in 1965 gives an eyewitness account of the Spirits Rejoice recording session. Guy’s photos of the session at Judson Hall are available on this site.]

Jazz Hot (No. 215, December 1965, p. 40) - France Le 23 septembre, Albert Ayler enregistrait un nouveau disque pour la marque ESP aux studios Bell qui sont situés à l’intérieur de la salle de concert du Judson Hall, dans la 56e rue, face au Carnegie Hall. Au moment où j’arrivai, Sonny Murray m’accueillit très cordialement et me présenta aux musiciens. Il y avait là Albert Ayler, plutôt petit, un sourire éternellement fixé sur son visage dont le menton se termine curieusement par un bouc, blanc d’un côté, noir de l’autre; le trompettiste Don Ayler, plus effacé que son frère, plus grand également, et le saxophoniste-alto Charles Tyler, placide et peu loquace. Il y avait encore Henry Grimes, qui accordait sa contrebasse dans un coin du studio. Dans un autre coin, Call Cobbs, qui fut l’un des accompagnateurs de Billie Holliday, s’exerçait sur une sorte de clavecin en réalité une harpe électrique et qui ne fut utilisé que pour un morceau. Albert Ayler, qui avait voulu la présence de deux bassistes, attendait l’arrivée de Gary Peacock par le train venant de Boston où Peacock vivait depuis plusieurs mois. Volubile, charmant, Albert Ayler fut ravi d’apprendre que ses disques commençaient à se vendre en France. Le technicien installa ses micros; les frères Ayler et Tyler répétèrent à trois le premier morceau. En choeur, ils jouèrent les premières mesures — à quelques variations près — de « La Marseillaise ». J’hésitai à me mettre au garde-à-vous, je n’en demandais pas tant... Tout en jouant, Albert Ayler arpentait le studio. Le technicien lui demanda de ne pas dépasser un certain périmètre lors de l’enregistrement. Gary Peacock arriva peu après avec sa contrebasse. Je ne l’imaginais pas aussi mince. Il alla dire bonjour aux musiciens qui l’accueillirent avec le sourire et installa son instrument qu’il se mit immédiatement à accorder. Je devais apprendre par la suite qu’il n’y avait eu aucune répétition avant l’enregistrement. Je fus encore plus surpris de voir les musiciens se lancer dans chaque nouveau morceau uniquement après qu’Albert Ayler ait donné quelques indications. Tous les musiciens étaient prêts. Bernard Stollman, le directeur de la marque ESP, leur demanda simplement si tout allait bien et monta dans la cabine de prise de son. Le photographe W. Eugène Smith, que beaucoup considèrent — et non sans raison — comme le plus grand des grands photographes, était également présent. Armé de mon modeste Pentax, je le vis, non sans une envie doublée d’admiration, déployer quatre appareils et se mettre à opérer silencieusement. Les musiciens enregistrèrent quelques mesures du premier morceau afin que l’ingénieur du son contrôlât la balance des micros et la séance commença véritablement. Pour les discrographes de l’an 2000, je signale qu’il était alors Albert Ayler semble mieux contrôler ses idées et son phrasé y a gagné en logique. Sa sonorité est telle que ses disques pouvaient la laisser supposer: explorant une gamme de tonalités dont peu de musiciens avant lui connaissaient l’existence, il emporte l’auditeur dans un flot de notes où la violence harmonique dispute l’attention à une tonalité désarticulée et belle dans son excès. Avec le support que lui fournissent Grimes, Peacock et Murray, il peut tout se permettre et se lance dans les idées les plus folles. Sonny Murray ne suit pas le soliste: il l’enveloppe littéralement, le recouvrant d’un déluge sonore sans comparaison dans l’histoire de la percussion. La tête le plus souvent penchée en arrière, il semble invoquer des dieux inconnus et lance au ciel une plainte où se mêlent douleur et plaisir. Il n’y a dans son jeu aucun des effets utilisés par les batteurs pour se faire applaudir invariablement en public. Sonny Murray utilisait pour cette séance un matériel restreint: une grosse caisse, une caisse claire, une « charleston » et une cymbale. Des baguettes creuses en aluminium lui permettaient d’obtenir une sonorité très sèche. Tout au long de la séance, Stollman a laissé une entière liberté à Albert Ayler et à ses musiciens. Ceux-ci avaient sélectionné les morceaux qu’ils jouèrent aussi longtemps que bon leur semblait. Ils éditeront eux-mêmes les bandes de l’enregistrement (il en va de même pour tous les autres disques ESP). La séance était terminée. Gary Peacock rangea son instrument; il repartait le soir même par le train de Boston. Entre deux morceaux, j’avais un peu bavardé avec lui. Il m’apprit qu’il s’était retiré à Boston où il ne jouait que très rarement et vivait un peu en solitaire. Converti à la religion « zen », Gary compte s’installer pendant une année ou deux sur une montagne pour y méditer. Le pianiste Burton Greene, qui assistait à la séance, devait me dire qu’il pensait que Gary vivait dans un monastère. Selon Albert Ayler, il loge chez ses parents qui possèdent une fortune personnelle. Lors d’une soirée au cours de laquelle nous nous rencontrâmes, il évoqua cette période de 1964 ou Gary Peacock, très malade alors qu’il se trouvait en Europe avec Ayler, Don Cherry et Sonny Murray n’avait réussi à retrouver la santé qu’en suivant un régime plus que strict: il ne mangeait rien. « C’est la méthode zen », précisa Albert Ayler. Guy KOPELOWICZ *

Jazz Magazine (No. 125, December 1965, p. 41) - France [This untitled article by Albert Ayler was his response to a questionnaire which had been sent to various avant-garde jazz musicians by Jazz Magazine. According to Alain Chauvat (who kindly sent me the relevant page of the magazine): ‘JM sent a questionnaire to many jazzmen/women from the “new thing”; the exception was Albert Ayler, who did not answer question by question (out of 10) but instead sent a written text. This issue of Jazz Mag #125 also had interviews with Cecil Taylor, Sun Ra, Ornette, Archie Shepp, Karl Berger, Carla Bley, Paul Bley, Jean-Louis Chautemps, Bill Dixon, Don Ellis, Don Friedman, Jimmy Giuffre, Eddie Gomez, Milford Graves, Don Eckman, David Izenzon, Bob James, Steve Lacy, Giuseppi Logan, Jimmy Lyons, Mike Mantler, Steve Marcus, Sunny Murray, Gary Peacock, Barre Phillips, Roswell Rudd, John Tchicai, Charles Tyler, Bernard Vitet, Lewis Worrell.’ Click the picture below to get a pdf of the original French version.] |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

An English translation of Ayler’s article was subsequently published in the International Times (London) in March, 1967, and Guerrilla (Detroit) January 1967: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

The rest of John B. Litweiler’s review of Spirits Rejoice is available here. ***

Next: Articles 2 (1966 - 1967) or back to Articles main menu

|

|||

|

Home Biography Discography The Music Archives Links What’s New Site Search

|

|||