|

|

|

|

|

Articles 7 (1971-1978)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ayler: still unsung in his home town by Bernard Lairet The Cleveland Press, 10 December, 1971 - USA

Albert Ayler by Alain Tercinet, Chris Flicker & Gerard Noel Jazz Hot, 1971, p. 22-25 - France

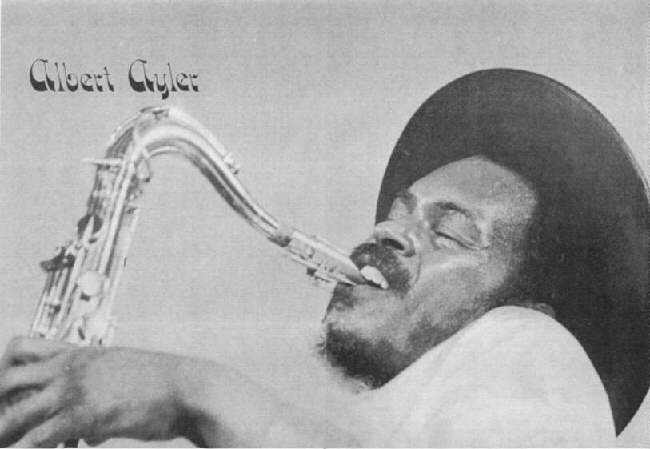

Albert Ayler by Martin Cowlyn The Professional, No. 2, February 1974 - UK

The Holy Ghost by Brian Case New Musical Express, 6 July, 1974, p. 40 - UK

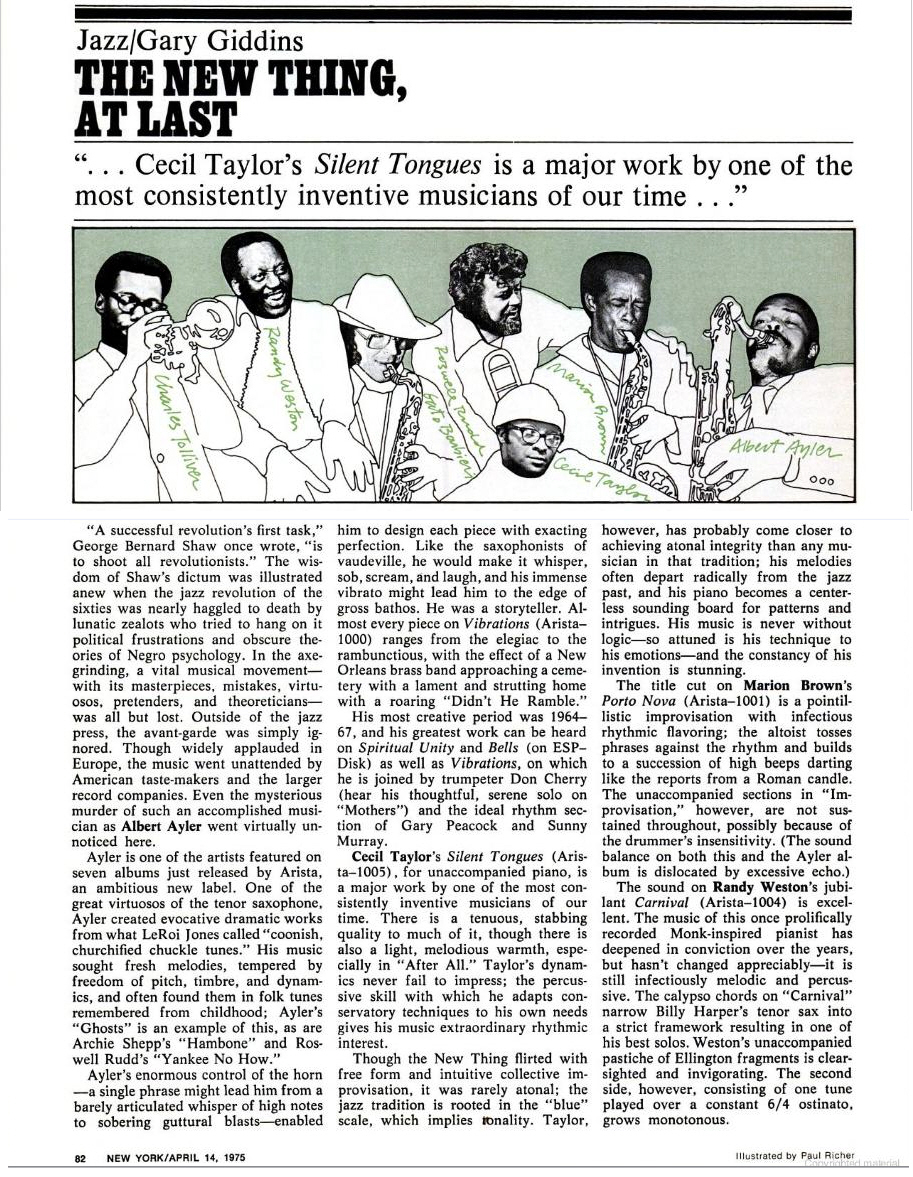

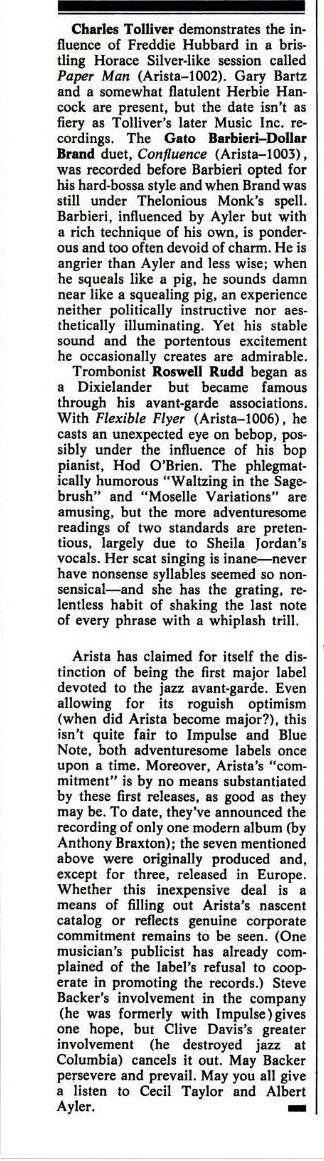

The New Thing, At Last by Gary Giddins New York Magazine, 14 April, 1975, p. 82-83 - USA

Ayler’s Apocalyptic Sound by Duck Baker Berkeley Barb, Vol. 21, No. 24, July 4-10, 1975, p.13 - USA

Albert Ayler Life and Recordings: A Dual Retrospect by Jon Goldman and Martin Davidson Cadence, April 1976, p. 8-13 - USA

*

The Cleveland Press (10 December, 1971) - USA

Ayler: still unsung in his home town

By Bernard Lairet

One year after the death of Albert Ayler, it does not seem that Cleveland, his native town and final resting place, yet has a better appreciation of his genius.

In New York, however, this sad anniversary has not gone unnoticed. besides articles in the New York Times and New Amsterdam News, last Sunday, radio station WKCR ran a 15 hour program completely devoted to his music and his memory.

In Paris, the French Broadcasting System has scheduled two programs of three hours concerning his life, his thinking and his musical contributions.

THE TWO ALBUMS that Albert Ayler recorded in France, on the Shandar label, a few months before his premature death, have received the International Award of the Charles Cros Academy (the equivalent of the American Grammy Award). In addition, the French Jazz Academy gave them the “In Memoriam” Award, and they have just been selected as the best records of the year for young people.

Recently, Count Basie, the old master, paid homage to Ayler in interpreting his exquisite composition, “Love Flower,” in his album “Afrique” (Flying Dutchman 10138).

AYLER WAS ONE of the predominant figures of today’s music, as well as one of the most revolutionary and controversial musicians jazz has ever had.

“If the people don’t like my music now, they will. Appreciation is a matter of time,” he believed.

It seems that each period of jazz history has its martyrs, exceptional soloists whose conceptions marked an entire era. They often died young, like Ayler at 34, frustrated by lack of recognition, never accepted within established American culture.

TODAY, AYLER’S influences become clearer, and his works (15 records), are already classic in contemporary music. But his legacy represents much more than that. All his life was sustained by a deep mysticism. His music transmitted a powerful energy, profound love, a kind of desperate god-seeking.

His untimely and still mysterious death seems a tragic absurdity. He had much more to give than the world could grasp and he suffered Cleveland’s indifference.

Back to Articles main menu

*

Jazz Hot (1971, p. 22-25) - France

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

UNE VIE

Albert Ayler nait le 13 juillet 1936 à Cleveland, Ohio (Donald, son frère et partenaire, voit le jour dans la même ville le 5 octobre 1942). Albert, qui a appris l’alto à age de dix ans, fait ses débuts dans diverses formations de rhythm and blues, dont celle de Little Walter Jacobs en 1952. En 1956, il adopte le ténor. Son service militaire, en 1960/61, s’effectue en grande partie à Orléans, caserne Coligny, en compagnie, entre autres, de Lewis Worrell. Albert, fait rare pour un musicien free, descendra en jouant les Champs-Elysées... un quatorze juillet (il avouera garder un excellent souvenir du chef d’orchestre français, qui l’aurait beaucoup influencé). Il vient à Paris les samedi et dimanche et essaye de faire le boeuf au « Chat qui Pêche », où il est fort peu estimé par les musiciens locaux. Libéré, Albert Ayler part pour la Scandinavie. C’est à cette époque qu’il se met au soprano. Il séjourne à Copenhague où les mêmes déboires qu’à Paris l’attendent. Cecil Taylor l’entend et veut l’engager dans son groupe qui passe au Café Montmartre. Malheureusement, le cabaret n’a pas les moyens et Ayler n’y jouera qu’occasionnellement. Le 25 octobre, il enregistre son premier disque pour la radio au Main Hall Academy of Music de Stockholm et le 14 janvier son second à Copenhague, pour la marque Debut, connu sous le nom de « My name is Albert Ayler ». Il passe à la télévision avec le même groupe.

De retour aux U.S.A., il partage son temps entre Cleveland et New York. Là, il joue avec le groupe de Cecil Taylor (Jimmy Lyons, Henri Grimes, Sonny Murray) au Philarmonic Hall le 31 décembre et au Five Spot en janvier 1964 pour un concert au profit du « Core ». (Il aurait également joué à la même époque, avec Ornette Coleman plus un bassiste et un banjoïste inconnus.) La marque Debut l’enregistre encore deux fois, puis le 10 juillet, c’est « Spiritual Unity » avec Gary Peacock (b) et Sunny Murray (dm) pour ESP. Le trio part en Europe au mois de septembre et récupère au passage Don Cherry. Ils jouent à Stockholm au Montmartre et, en décembre, à Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Alkmaar et Hilversum.

Albert Ayler, de retour à New York, donne différents concerts au cours de l’année 1965: Cooper Square (fév.), Village Gate (28 mars), Town Hall (1ier mai), Haryou Act, Harlem (oct.), Black Arts Theatre (déc.). En janvier 1966, il passe au Slug’s avec son propre groupe, puis avec Burton Greene. Le 19 février, Ayler joue au Philarmonic Hall avec John Coltrane (My favorite things, Om). Il est à Cleveland, en avril avec, pour la première fois comme partenaire, le violoniste hollandais Michel Sampson, ancien élève de Nadia Boulanger. Le groupe d’Albert Ayler fait également partie du dernier des trois concerts organisés par « Lovebeast Enterprises » sous le titre « The Avant Garde : A perspective in Revolution » (26 août).

Albert Ayler, Don Ayler, Michel Sampson, Bill Folwell, Beaver Harris partent en Europe avec les « Newport Jazz All Stars » : Berlin (3 nov.). Paris (13 nov.), Londres (15 nov.). Dans cette ville, ils enregistreront deux programmes pour la TV, au cours d’un concert au Conway Hall, organisé par « The London Free Schools », programmes qui ne seront jamais diffusés.

A.N.Y., Ayler passe au Village Vanguard (18 décembre) et au « Village Theatre » (26 février et avril 1967). Avec Don Ayler, Michel Sampson, Alan Silva, Milford Graves, il joue au Festival de Newport le 1ier juillet 1967. Trois morceaux seront interprétés: « Universal Indians », « Our Prayer » et « Truth is marching in ». Ce même thème, Albert, Don, Richard Davis, Milford Graves l’interprêtent le 21 juillet aux funérailles de Coltrane (St Peter’s Lutherian church). En septembre, il passe au Slug’s et au Café à Gogo pendant l’été 1968.

Il enregistre les 5 et 6 septembre, le disque « New Grass » qui, pour certains, marque un tournant dans sa carrière. Il récidive dans cette voie les 26, 27, 28, 29 août 1969, avec l’album « Music is the healing force of the Universe ». (9) en compagnie de sa femme Mary Maria. Il joue de la cornemuse dans un morceau et, dans un autre, adresse un salut amical au rhythm and blues de ses débuts en compagnie d’Henri Vestine, le guitariste des « Canned Heat ».

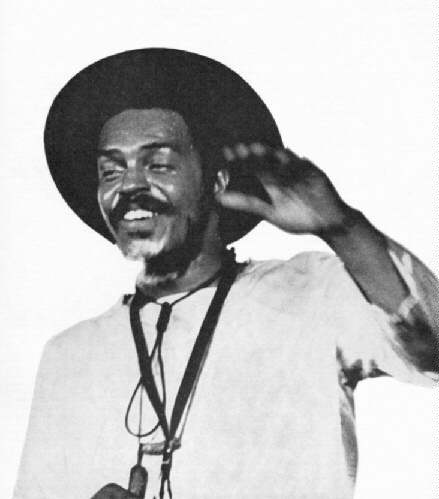

Albert Ayler joue les 25 et 27 juillet 1970 aux « Nuits de la Fondation Maeght », à St Paul de Vence. Son orchestre se compose de Mary Maria (ss, voc.), Steve Tintweiss (b.), Allen Blairman (dm.). Call Cobbs (p.) les rejoindra pour le second concert seulement. Le succès remporté est immense.

Albert Ayler avait disparu de son domicile depuis le 5 novembre, son corps fut repêché dans l’East River à New York le 25 novembre 1970. Ses obsèques se sont déroulées très discrètement le 4 décembre, au cimetière d’Highland Park de Cleveland.

Alain Tercinet.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Scandinavie: 1964: Sunny Murray (dm), Gary Peacock (b), Albert Ayler (ts), Don Cherry (tp).

A LA RECHERCHE DU TEMPS PERDU

Once upon a time... Rien ne commence jamais ainsi dans les colonnes du « New York Herald Tribune ». Non. Tout y finit par quelques mots très secs, très durs, précis comme le scalpel du médecin légiste:

« Cleveland, dec. 4. A funeral service was scheduled today for Albert Ayler, 36, who emerged in the 1960s as one of the most prominent saxophonists in the avant-garde jazz movement. Mr Ayler’s body was found in New York City’s East River on the morning of Nov. 25. »

Once upon a time... Quelque part dans les rues de Cleveland il était un petit bonhomme de dix ans semblable à beaucoup d’autres, sauf qu’il avait la chance de jouer sur un bel alto bruyant et brillant, en compagnie de son père, dans les orchestres qui accompagnent là-bas les enterrements. Ceci lui donnait un grand prestige auprès des autres gamins. Car tous les enfants ont le sens du Sacré, du Merveilleux, de l’Angoissant. Ils sont tous fascinés par les histoires de fantômes, d’esprits, de revenants; ils connaissent les délices douloureux de la peur et des ombres. Mais aussi ils adorent les fanfares, les cuivres, les marches, les défilés.

Les adultes aussi retrouvent parfois cette jubilation désordonnée que procure le son glorieux du clairon, des cymbales, de la grosse caisse, pour ces bacchanales contemporaines que sont le carnaval de Rio, a fête de la bière à Munich ou la Feria de Pampelune. Il n’est que de voir les ravages qu’ont causés les gros flon-flons de la fanfare des beaux-arts pendant le Musicircus de John Cage pour s’en rendre compte. Qui niera le rôle des sonneries dans ces profonds mouvements qui empoignent la foule au ventre et la soulève, à Séville dans la Semaine Sainte, ou à 5 h du soir sur les gradins des arènes? Et ce n’est pas hasard si de telles musiques préludent aux grandes orgies collectives et sanglantes, aux déchainements ténébreux de l’instinct de destruction sur la terre rouge des champs de bataille.

Tout un chacun a peu ou prou été cet enfant de dix ens réceptif aux échos du monde, perméable aux « minorités » musicales, attentif aux rengaines, aux chants rituels: les fanfares du cirque, les marches militaires, les chants de Noël, les cors de chasse, les berceuses, les choeurs de l’Armée du Salut, les comptines et les rondes, les orgues de barbarie et les binious bretons.

Si l’on remonte aux premiers âges du jazz, aux fanfares de la Nouvelle-Orléans, n’est-ce pas ce vaste fond de culture populaire que l’on retrouve? (assimilé par les Noirs coupés de leurs racines).

Tout un chacun a oublié cet enfant aux goûts primaires qu’il était pour devenir un être de culture. Oubliées les voix de fausset, criardes et enthousiastes, oubliés les « Jésus que ma joie demeure » aux harmonies approximatives. Albert Ayler lui n’avait rien oublié de son enfance, de l’enfance.

En 66 le revoilà avec sa cohorte de thèmes significatifs: children, ghost, spirits rejoice; holy ghost, mother, angels, bells et autres witches and devil.

On lui a donné un titre: Albert Ayler ou la dérision de la culture occidentale. La dérision... Sacré Ayler! Qu’est-ce qu’il a rigolé en 66 à Pleyel. Très fort, il fallait bien montrer que l’on avait compris la plaisanterie. Child, you work to hard; every time I see you diggin’ and diggin... ou les dangers du deuxième, troisième ou nième degré.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

En haut: Pleyel 1966: Don, Albert Ayler, Bill Folwell (b), Michel Sampson (v), Beaver Harris (dm).

En bas: Maeght 1970: Mary Maria et Albert Ayler.

C’était bien plus simple; à la portée d’un enfant de dix ens (eux ne s’y trompaient pas d’ailleurs). Essayez sur vos gosses, le résultat est garanti.

A-t-on jamais soupçonné Paul Klee de faire de la peinture par dérision? Et cette culture occidentale, cette sous-culture plutôt, mais c’était celle d’Ayler (Le retour à la mère afrique n’est qu’un fait social second, le résultat d’une prise de conscience, un mouvement volontaire, engagé). Nulle dérision dans sa démarche; ou, au pire, la dérision de la dérision.

L’accélération de l’histoire fait que les styles, les écoles ne se succèdent plus chronologiquement en amples mouvements dichotomiques comme dans les pages de Lagarde et Michard. Ils foisonnent, se superposent, coexistent: New Orleans, bop, gospels, cool, swing, free jazz, rhythm and blues, pop music, toutes les tendances existent en même temps. Et cela simplement dans la musique dite de jazz.

Mais approchez un peu votre oreille du transistor, tripotez les boutons de la machine folle, écoutez les voix disparates de l’univers qui est le nôtre...

Albert Ayler s’est trouvé au point où l’accélération du mouvement devient tel qu’on atteint l’immobilité, où l’on cesse d’être poussé à la pointe d’une actualité linéaire qui devient folle, où l’on sort du carcan des modes cycliques. On a beaucoup parlé du pop art, d’un art populaire utilisant les éléments vulgaires de notre vie quotidienne. En ce sens Albert Ayler était une sorte de précurseur du pop art, et même du dirty art (il faut bien parfois utiliser ces terminologies barbares) puisqu’il a utilisé les plus méprisées, les plus « triviaux » des genres musicaux. Un précurseur sans le savoir, un précurseur sans le vouloir. A la différence de tant de musiciens qui « font » dans la pop music pour des motifs divers et pas toujours honorables, il a vécu la musique pop comme un phénomène qui fait partie de notre environnement (publicités à la radio, fond sonore dans les supermarchés, etc.).

Il portait sur ce tintamare discordant, sur cet amas hétéroclite un regard non pas nouveau (qui de se vouloir opposé à l’ancien en demeure entaché) mais un regard innocent, pur et rendait ce matériau beau et joyeux. Il prouvait que par la vertu d’un regard naïf, celui de l’enfant du roi nu, le conte d’Andersen, tout peut être changé. He men, open your eyes and dig it!

Et voilà que quatre mois après les concerts de la fondation Maeght, quatre mois après le triomphe que lui fit une salle bouleversée, dépouillée de ses idées reçues, lavée de ses arrière-pensées d’esthétisme, oublieuse des exigences de l’analyse et des barèmes du bon goût, l’Alchimiste n’est plus qui changeait les métaux vils en or pur, leur rendait leur éclat d’origine.

« A man is like a tree », chante Mary Maria, « comes the change of the seasons, he dies and HE’S BORN AGAIN... ». Sonnez haut-bois, résonnez musettes.

Dolphy, Coltrane, Ayler... Malgré Sun Ra, la ville est ce soir un peu plus sombre.

Chris Flicker.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

L’ART ADMIRABLE D’ALBERT LE TEMERAIRE

« Je joue pour la beauté qui surgira après tous les conflits et toutes les anxiétés. Cette musique parle de cris d’après guerre; je veux dire de cris d’amour que l’on peut déjà entendre chez les jeunes et qui apparaîtront quand les hommes qui recherchent la paix atteindront la paix spirituelle. »

Albert AYLER.

Albert Ayler. Deux images restent gravées dans notre mémoire: Paris, Salle Pleyel, 13 novembre 1966; il se fait tard, le concert s’est déjà longuement étendu; un public étonné, partagé, ne sachant pas trop quelle attitude adopter, doit subir les assauts d’un petit homme rigolard qui, sous sa barbiche noire et blanche, tenant bien haut son instrument devant lui, fait mine de marcher vers la salle en exécutant une incroyable « Marseillaise ». Saint-Paul-de-Vence Fondation Maeght, fin juillet 1970; il est tard encore une fois, Albert Ayler, chapeau aux larges bords, longue aube candide, tente de ranger ses saxes dans leurs étuis; un petit groupe l’entoure, il a l’air exténué; « je suis tellement heureux, mes amis, je veux que vous sachiez... ma musique est une musique d’amour... merci... merci... » Et puis le 7 décembre, l’incroyable nouvelle, brute, sans explication, sans rien d’autre que le coup porté au coeur de ceux qu’avait touchés l’art poignant et déroutant de cet homme tout simple: le corps d’Albert Ayler a été retrouvé dans l’East River, on ignore tout des causes de sa mort.

Albert Ayler aura sans doute été le musicien le plus controversé de ces dernières années. C’est qu’il n’était réductible qu’à lui-même, que sa musique n’évoquait en nos imaginations rien d’autre qu’elle-même, absolue dans son éruption. A Cecil Taylor, l’on reconnaissait une technique instrumentale hors du commun; Shepp, par son amour de la tradition et sa capacité de la revivifier quelles qu’en soient les formes, pouvait convaincre les plus rétifs des amateurs; Sanders avait été appelé par Coltrane et de son instrument sourdait de temps à autre une joliesse aisément assimilable. Ayler, lui, avait assigné à sa musique un but unique auquel tout était subordonné; il lui fallait toucher, émouvoir; de là vient que seuls ceux qui acceptaient de se libérer d’eux-mêmes, de faire le vide dans leur esprit classificatoire pour s’étonner du monde pouvaient ne pas s’étonner de sa musique.

Celle-ci, autre signe qui la distingue de la plus grande partie du reste de la production « free », était une musique de joie. Seul, il avait imposé d’emblèe un lyrisme qu’on pensait devoir disparaître; le premier il avait compris que, dans la double démarche qui caractérise la « new thing », destruction de l’ancien langage, reconstruction d’un art nouveau — image de désaliénation culturelle, les deux phases pouvaient et devaient être conduites dans le même temps.

Albert Ayler, très rapidement avait su se donner les moyens de cette fin, éléments de discours qu’il lui fallait forger à partir d’une collecte de segments épars, là où rien d’organisé ne correspondait encore à la matérialisation de ses idées. Ses deux premiers disques suggèrent ce qu’a pu être cette quête: enregistrés en Scandinavie avec le concours de musiciens traditionnels quelque peu distants, ou plutôt « distancés » (sans pour cela que leur travail fût aussi excécrable qu’on a bien voulu le dire), elle y prend pour prétexte les canevas classiques qu’offrent des standards rabachés: Moanin’, On green dolphin street, Softy as in a morning sunrise, etc. Dès le départ pourtant, Ayler réussit à graver un chef-d’oeuvre: Summertime. Le contour selon lequel il aborde ce thème n’est pas encore spécifiquement « free », à vrai dire, l’on songerait plutôt au Lover Man de Parker (de même que dans Rollin’s tune (3), c’est bien évidemment Sonny Rollins qu’évoque Albert Ayler), mais les modalités expressives de cette oeuvre contiennent déjà en puissance tout ce qui sera développé par la suite. Le saxophoniste y suit de très près la mélodie tout en pratiquant d’étranges coupures de façon à faire exploser des noyaux qui, à notre sens, sont plus émotionnels que purement musicaux. Un an après, nous disposons de témoignages prouvant que la musique d’Ayler est très rapidement arrivée à maturité. Il y met en oeuvre une conception du phrasè absolument « révolutionnaire »; après quelques essais empruntant à Dolphy et à Rollins où le concept de note a encore quelque signification, Ayler en arrive à la construction d’un flux mâchonné qui s’écoule sans que rien ne le rattache aux constructions habituelles des improvisations, où les notes sont fondues les unes dans les autres, superposées, rendues en fait indistinctes pour que seules soient sensibles à l’auditeur les notions d’intensité et, surtout, de hauteur de son. La sonorité est éraillée au possible, criante, grinçante, construite dans le foisonnement des harmoniques, des sifflements et autres sons «impurs» (Ayler, paraît-il, employait une anche en plastique, les anches en bambous ne résistant pas au travail qu’il leur imposait). La thématique est fixée également avec ses connotations ésotériques ou religieuses: Ghost, Wizzard, Spirits, Witches and devils, etc., avec son alternance de mélodies très simples jouées avec grandeur voire grandiloquence et de marches militaires ou de sonneries de Saint Hubert traitées avec un humour corrosif. D’autres traits sont d’ores et déjà sensibles: le refus du rythme scandé, celui-ci s’évanouissant dans un bruissement de cymbales et dans un martèlement assymétrique des caisses qui dessinent simplement un « entourage agissant » autour du jeu du saxophonisté; toujours (sauf dans ses interprétations de Rhythm and Blues) Ayler s’en tiendra à cette non directivité de la rythmique, le swing étant obtenu par la conjonction des jeux de tous les instruments. L’attrait d’Ayler pour les cordes est également marquant (attirance pour des sons facilement grinçants et désarticulés?); il s’entourera toujours d’excellents bassistes, en utilisera deux quand il le pourra et choisira des musiciens qui savent faire jouer toutes les capacités vibratoires des cordes de leur instrument (Peacock en particulier); il se plaira à jouer en compagnie de violoniste (Michael Sampson) ou de violoncellistes (Joel Friedman); enfin, plutôt qu’un piano, c’est un clavecin (Call Cobbs) qu’il placera à ses côtés. De même, dès cette époque, le seul instrument que l’on puisse rapprocher de son saxophone est la voix humaine, mais une voix brute, « primitive », jamais travaillée dont le registre s’étendrait pourtant des basses aux plus aigus des sopranos. Ayler d’ailleurs ne tardera pas à doubler de la voix son chant instrumental, son discours plus exactement, et à partir de Love Cry vocalisera selon un phrasé semblable à celui qu’il emploie instrumentalement; par la suite Mary Maria le relaiera.

Au fil des disques suivants, ces caractéristiques de la musique Aylérienne resteront présentes avec sans doute une tendance à laisser plus de place aux mélodies, au lyrisme, à la joie pure (1) alors qu’auparavant, il était possible de déceler dans son art des traces de colère.

Cette sérénité, cette joie de jouer et de créer une musique joyeuse était, nous l’avons déjà dit, l’une des originalités de l’art Aylérien. Cette joie n’a rien de superficiel, cependant, rien de mystificateur; elle ne provient pas d’un refus de voir la vie telle qu’elle est, la réalité avec tout son cortège de brutalités, d’exploitation, de tristesses. Au contraire. Ayler ne veut pas être autre chose que ce qu’il est: « un paysan de l’Ohio qui s’est enthousiasmé pour la musique en écoutant Lionel Hampton » ainsi que le définissait, avec sa pertinence coutumière, Jean Wagner (2). Ayler est du peuple et veut faire « une musique du peuple pour le peuple » (3). De ses origines campagnardes et populaires, de Lionel Hampton, ce qu’il a retenu, c’est la Fête: ce rassemblement de la communauté où s’affirme la cohésion sociale, où, quelles que soient les sombres réalités du monde alentours, éclate la joie d’être ensemble, de partager ensemble ce qui est commun à tous (ainsi en est-il des concerts d’Hampton où toujours, plus ou moins heureusement, sont restitués les mêmes airs). Ayler aussi a été musicien de blues et a tenu à se réaffirmer comme tel à plusieurs reprises (New Grass (4), Drudgery et ce Holy Family en forme de twist!); il enregistra également un disque de Negro Spirituals jamais publié jusqu’à maintenant. Tout ceci fait de lui un musicien afro-américain au plein sens du terme, un musicien de sa communauté qui joue pour sa communauté: de là vient l’aspect prêché de son discours (avec, aisément décelable, un accent campagnard qui écorche les mots, mêle les syllabes), la volonté de jouer des mélodies simples (qu’il est aisé de siffloter après les avoir entendues), entrainantes et souvent jolies, la volonté d’utiliser des formes dont le caractère populaire — lié à la Fête — soit indéniable: le blues et peut-être plus encore le biguine Island harvest (5) et Ghost (6), qui, fait significatif, était en quelque sorte son indicatif), la volonté enfin d’en revenir aux sources: à l’improvisation collective néo-orléanaise (7), à la voix humaine dans toute son âpreté (field hollers).

Si, comme le remarquait Jean Wagner dans l’article déjà cité, ce caractère délibérément populaire de la musique d’Ayler n’entraine « aucune implication politique dans son propos », cela « n’empêche pas, par ailleurs, sa musique d’avoir une signification politique précise ». Ayler, en effet, n’entrecoupe pas sa musique de grands discours, d’ « Uhuru » (8) criés sur tous les tons, mais il sait la réalité du monde dans lequel il vit, il témoigne pour ce monde et crie la nécessité de le changer: « Il semble qu’aujourd’hui le monde cherche à se détruire. Et pourtant, beaucoup de gens parviennent à juger le monde avec un regard objectif. Ils voient la méchanceté, l’hypocrisie, l’injustice et le dur travail que doit fournir l’être humain pour gagner très peu de chose. Si seulement nous voulions bien penser à ces choses, en pénétrer notre CONSCIENCE INTERIEURE — spirituelle — nous comprendrions qu’il nous faut livrer une bataille sans fin (avec nous mêmes) avant de triompher de tous les obstacles, avant d’avoir acquis le désir véritable de changer » (9) et, un peu plus loin, « quand la MUSIQUE change, les gens changent aussi » (10).

Ce texte est extrêmement intéressant dans la mesure où il montre le niveau de conscience atteint par un musicien engagé dans un mouvement (donc un collectif) esthétique dont la portée, la signification le dépassent en tant qu’individu. Albert Ayler y parle d’injustice, de dur travail pour gagner peu de chose, il parle de changement et de la nécessité d’une bataille pour le provoquer. Par contre, Ayler situe ce changement dans la conscience intérieure, il présente la bataille comme devant être livrée avec nous-mêmes. A aucun moment il n’évoque la nature du pouvoir aux Etats-Unis et dans le monde capitaliste, le racisme et l’exploitation qui le sous-tend. Pourtant, il invoque finalement (comme Cecil Taylor et Archie Shepp, musiciens sans doute beaucoup plus « conscients », l’ont fait par ailleurs) la nécessité d’une « révolution culturelle » ou tout au moins la possibilité de modifier les mentalités à l’aide d’une production esthétique: notre musique « essaye d’aider chaque être humain à susciter en lui de nouvelles attitudes face à la vie » (11). La conscience d’Ayler est donc enserrée dans une gangue idéologique qui se résume schématiquement en une ritournelle connue: « aimons-nous les uns les autres » (12).

Sa musique, encore une fois cette production esthétique qui témoigne de façon plus ou moins distante, avec plus ou moins d’autonomie, mais qui témoigne cependant, des structures de la société englobante, possède, elle, une portée beaucoup plus révolutionnaire que ce type de réflexion et cela, par-delà même ses cadres formels: le contenu du signifié latent dépasse largement celui du signifié explicité par les commentaires du producteur et rejoint en fait la révolutionnarisation des formes apportée par le signifiant. Il faudrait une analyse beaucoup plus détaillée et portant sur l’ensemble du mouvement — le « free jazz » — pour illustrer clairement ce qui vient d’être dit ici.

En bref, la nécessité profondément ressentie de se couper des sources d’inspiration occidentales (blanches), de tous les concepts du « beau », du « mélodieux », de l’ « harmonieux » imposés jusqu’alors à la musique afro-américaine (Benoit Quersin disait il y a bien longtemps déjà qu’Albert Ayler produisait « un déconditionnement total absolu, au point qu’on le soupçonnerait presque de n’avoir jamais entendu de musique occidentale » (13); le procédé de « dérision » infligé à la musique occidentale dans ce qu’elle a de moins convaincant; la libération totale entreprise du point de vue de la technique instrumentale; tous ces éléments opposés à la volonté de créer une musique populaire authentiquement afro-américaine, qui se situe dans l’esprit des fêtes traditionnelles; à un processus de retour aux sources symbolique, ne tracent-ils pas un parallèle frappant avec l’idéologie en formation des mouvements révolutionnaires afro-américains?

En fait, Ayler était encore une fois à l’avant-garde, un peu comme Sun Ra, il créait une musique pour demain, pour la société nouvelle qui sortira de la lutte en cours et le ressentait confusément sans pouvoir l’exprimer clairement. Sa musique était une musique de lutte et de victoire alors qu’il tentait de se cacher à lui-même la nature véritable de cette lutte. Qu’importe au fond puisqu’avant toute autre chose demeure son message — sa musique — dont la simplicité et la pureté ne manqueront jamais d’émouvoir ceux qui acceptent que leurs creilles entendent et que leurs yeux voient, en même temps.

Gerard NOEL.

(1) Cf. Omega in Love Cry.

(2) Jazzmag no. 182.

(3) ibid.

(4) in Music is the healing force of the universe Impulse A 9191.

(5) ibid.

(6) ESP 1002 et divers autres.

(7) Cf. Truth is marching in in Live at the village vanguard.

(8) Liberté, indépendance en Kiswahili, langue de l’est africain.

(9) Jazzmag no. 125.

(10) ibid.

(11) notes pour Live at the village...

(12) Cf. Message from Albert in New Grass.

(13) Jazzmag no. 115.

Back to Articles main menu

*

The Professional (No. 2, February 1974) - UK

Albert Ayler by Martin Cowlyn

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Back to Articles main menu

*

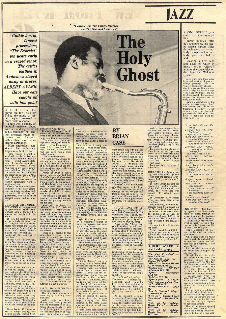

New Musical Express (6 July, 1974)

The Holy Ghost by Brian Case

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Back to Articles main menu

*

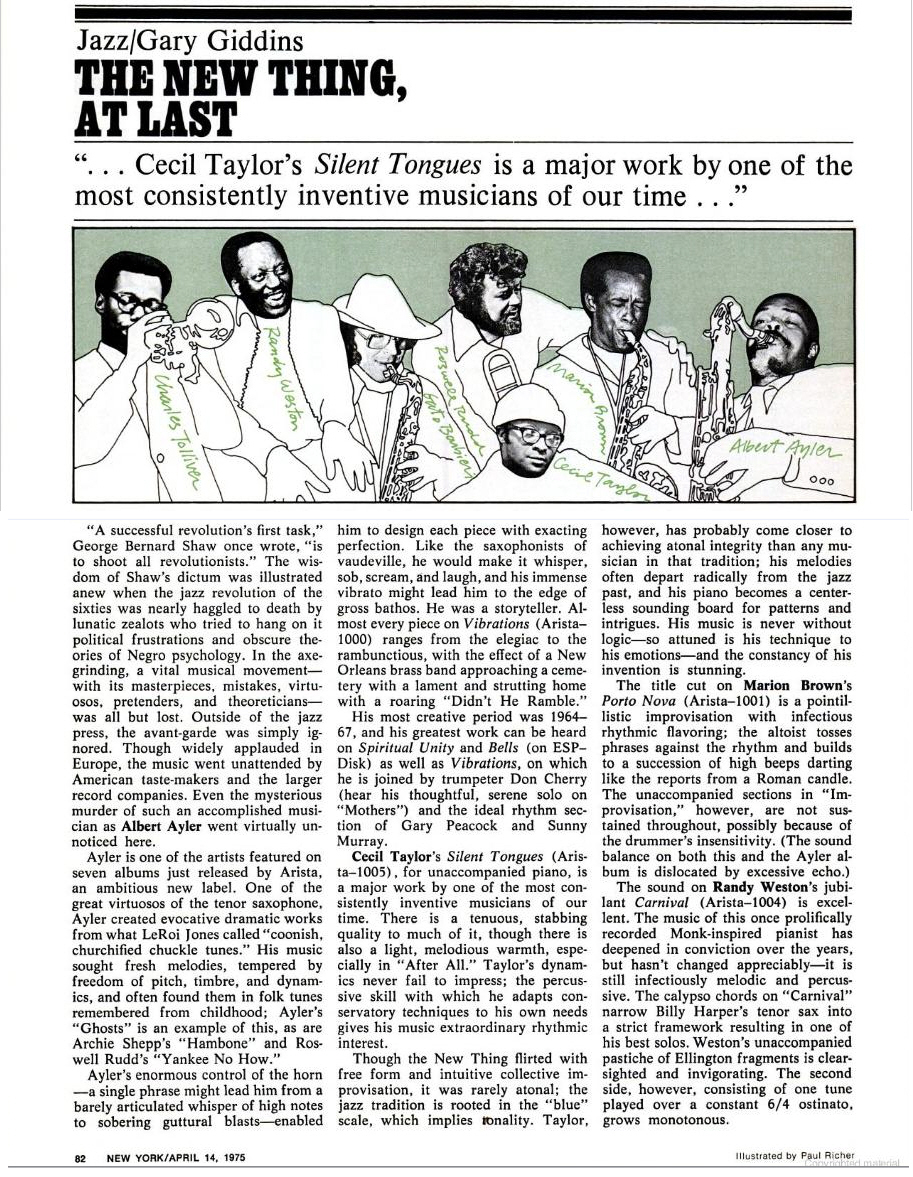

New York Magazine (14 April, 1975, p. 82-83) - USA

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Back to Articles main menu

*

Berkeley Barb (Vol. 21, No. 24, July 4-10, 1975, p.13) - USA

Ayler’s Apocalyptic Sound

by Duck Baker

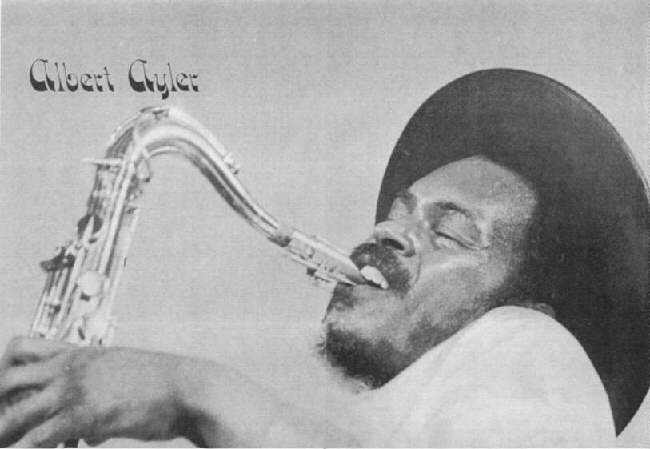

Albert Ayler is one of the pivotal figures of twentieth century music. His music represents the final stage in the development of “jazz” into an all-inclusive, universal folk music. As of 1975, for all the expansions of contemporary music achieved by The Art Ensemble, Anthony Braxton, and the British school, nothing has come forth to compare in intensity to the apocalyptic outpourings of Ayler during his peak period ten years ago. VIBRATIONS, formerly GHOSTS on the hard-to-find Dutch Fontana label, is one of Ayler’s greatest records, and the most important release on the newly-formed Arista-Freedom label.

A listen to VIBRATIONS will give an idea why discussion of Ayler’s contributions so often read like exercises in hyperbole. It is not an easy record to listen to, a fact which may make it sound a little dated in light of the current search for the ultimate in superficiality, à la Corea, Hancock or Jarrett. But for anyone still interested in the deepest and most catalytic expressions of the human condition, it is a vital and life-giving creation.

Ayler’s first two records are strange, abortive dates owing to attempts by record companies to fit his music into pre-existing categories. On Albert Ayler, on First Recordings, on GNP, the results of this meddling are somewhat comical, and his playing is often very good, despite the total incongruity of the straight rhythm sections. Later, when Impulse Records was calling the shots, the results were much worse. On the currently hard-to-find Witches and Devils (Polydor), Ayler was able, for the first time, to record his own music. His colleagues on this 1964 date were trumpeter Norman Howard, bassists Henry Grimes and Earle Henderson and drummer Sunny Murray. Although not as overwhelmingly convincing as the two records to follow it, WITCHES AND DEVILS is a fully-realized creation, demonstrating dramatically what a strong and unique conception Ayler possessed.

In many ways, Ayler’s music was the most extreme to come out of the revolution fostered primarily by the work of Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor in the late fifties (Sun Ra’s unsubstantiated claims regardless). Ayler took the folk-like “primitive” approach of Ornette to its ultimate conclusion; even Ornette makes some use of chords in his improvising—although it is the most basic kind of use. Ayler abandons chords and even note-values altogether. His heads are the simplest possible folk melodies, things a child might hum. Yet in Ayler’s music they serve as condensed kernels of energy, which explode into space in a way which is really indescribable; you have to hear it.

The effect of Ayler on other musicians was immediate and profound. Cecil Taylor, with whom Ayler worked during 1962-64, recently described Ayler, in Bells newsletter, as “the greatest virtuoso of the tenor saxophone. He influenced many players, including Coltrane.” Coltrane himself said that he once had a dream in which he played like Ayler, but had never been able to do it. (Coltrane’s last recordings, Expression and Intersteller Space, on Impulse, show that Trane was in the process of wedding his own unmatched harmonic sophistication with Ayler’s wild energy at the time of his death.) And Paul Bley, in a Downbeat interview last year, expressed his belief that Ayler was the last great acoustic virtuoso, and that only by going into electronics could the music go beyond the plateau to which Ayler had taken it.

Ayler’s two greatest records by most counts are VIBRATIONS, which is finally easily available in the U.S., and SPIRITUAL UNITY, the first record he made for ESP-Disc. UNITY was made in the company of Murray and bassist Gary Peacock, and the same group plus trumpeter Don Cherry made VIBRATIONS a few months later. The music on these particular records are beyond criticism, in my mind. There is no way in the world anyone can add to the perfectly articulate sounds on these records; they are comparable to whatever summit of musical expression you might refer—Parker’s Dials, Oliver’s Gennets, Sun Ra’s Heliocentric Worlds, Boulez’s Marteau Sans Maitre, Beethoven’s last quartets, whatever.

The other two ESP records under Ayler’s name, SPIRITS REJOICE and BELLS, are nearly as great. On these records, Ayler shares a free front line with his brother, Donald, a wild blower on trumpet who lacked the great subtlety of Don Cherry but fit into the fiery ensembles well; and altoist Charles Tyler, who plays beautifully with Ayler, especially on BELLS. Another record of ESP, NEW YORK EYE AND EAR CONTROL, was a film sound track which brought together Ayler, Cherry, Murray, and Peacock with trombonist Rudd and altoist John Tchicai. Ayler is the dominating force on the record, and he (and everyone else) plays beautifully, but it is not as cohesive as the other Ayler ESPs, principally because of the clash between Ayler’s extroverted style and the introspective playing of Tchicai. Rudd, and especially Cherry, react to both sides, but Ayler and Tchicai remain inflexible. Nevertheless, NEW YORK EYE AND EAR CONTROL is a fascinating record with many beautiful moments, and is very underrated. I personally think it’s much better than either Coltrane’s Ascension or Ornette’s Free Jazz.

The last record which is indicative of Ayler’s greatness is LIVE IN THE GREENWICH VILLAGE, his first Impulse date and one fully as jubilantly beautiful as BELLS and SPIRITS REJOICE. The next Impulse, LOVE CRY, is a disaster but not nearly as grotesque as what followed—NEW GRASS, MUSIC IS THE HEALING FORCE OF THE UNIVERSE, and LAST ALBUM. 1 still remember my shock (shared by others) when I first saw LOVE CRY in a record store, grabbed it, took it home and put it on. I think that that record, along with Pharoah Saunder’s anemic Karma, made me aware of the change in the jazz world following Coltrane’s death in 1967.

Whether, as has been alleged, Impulse’s determination to make pop stars out of their artists was responsible for the change in the output of Ayler, Shepp and Saunders, or the absence of Coltrane as a guiding influence, or the sincere desire of these men to reach more people was responsible, virtually nothing that these three, once considered the obvious keepers of the flame, have done since Trane’s demise has been worth hearing. Exceptions to this gloomy truism are Shepp’s spectacular Life at the Dohaushingen on Saba, his The Way Ahead, on Impulse, and the two records of Ayler live on Shandar, a French label with unlimited distribution.

These records, recorded in 1970 (after THE LAST ALBUM) show that Ayler was still capable of playing beautifully, but the supporting band, to my mind, is much weaker than those of the earlier days. Like the first two records, the last two provide only a glimmer of the brilliance of Ayler’s genius.

In November 1970, Ayler’s body was found floating in New York City’s East River, a bullet in his head. This shocking end for one of the great creators of our times has never been explained to anyone’s remote satisfaction. Some say his death was suicide, motivated by depression over various personal problems, among them his inability to reconcile the beautiful world his music spoke of so vividly with the “realities” of the Great Society. Others, who cannot reconcile the idea of suicide by such an incredibly vital purveyor of the life force as Albert Ayler, have been inclined to accept the possibility that Ayler was murdered.

As a Washington D.C. musician, Bishop Brock, told me, “Man, you know who killed Albert Ayler. He was a revolutionary force, and the people on the other side knew it.” Maybe they did. One way or the other, the circumstances of his death froze the blood of a lot of people in 1970 when it was obvious that his death had a symbolic implication even beyond the fact that another of America’s great artists had, like Bessie Smith, Fats Waller, Charlie Parker, Clifford Brown, and Eric Dolphy (all of them happen to have been black) died a tragic, premature death. That implication, of course, was that the “new thing,” as it was called, the beautifully free and liberating music of the sixties, died with Ayler.

Nowadays, unless you catch Cecil Taylor or Ornette or Sam Rivers at their best, you won’t hear music anymore. True, the Art Ensemble, Braxton and the English players are taking the music in beautiful new directions, but compared to BELLS, it’s all as “cool” as Al and Zoot.

Back to Articles main menu

*

Cadence (April 1976, p. 8-13) - USA

Albert Ayler Life and Recordings

A Dual Retrospect by Jon Goldman and Martin Davidson

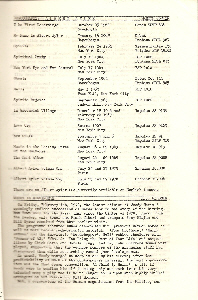

The numbers in parenthesis in the following two articles (#1-17), refer to Ayler recordings. The album titles and numbers are listed at the end of the articles on page 13.

One of the great tragedies about Cleveland is that while it may nurture talent up to a point, it does not provide an expansive base sufficient to allow an avant-garde to develop. If an individual artist shows any promise of growing into a major stylist or innovator, he or she has to get out because often we are not ready to give the necessary recognition and opportunity for expression of new ideas. In the thirties Art Tatum presided at “Val’s In The Alley”; in the forties Tadd Dameron played along with brother Caesar (who remains here) and in the fifties, Jim Hall lived here and studied at the Institute of Music. In the sixties, Albert Ayler tried to expose us to his music and he lost the battle more than once. We simply were not ready.

Ayler, who died in New York in 1970, was possibly the most original tenor saxophonist to come along since John Coltrane, but recognition of his talent was slow in coming. His musical experience went back to the time when, as a ten year old, he played alto saxophone at funerals in Cleveland as a member of a band in which his father played tenor saxophone. After performing in concerts and church musical gatherings, at sixteen he went on the road for four months with Little Walter Jacobs’ Rhythm and Blues band. Around 1956 he switched to tenor, his main instrument, until his death. When Albert went into the Army, he found his way into the Army Band which took him to Europe where he first made his mark on musical history. In fact, he was not only forced to leave Cleveland, but the United States altogether, in order to get someone to listen. I was told years ago that when Albert attempted to sit-in in Cleveland bars, such as the now-defunct Esquire on Euclid at E. 105th, he was forcibly ejected from the stand (even by such a luminary as once local musician Rahsaan Roland Kirk). Why was Cleveland not ready for a musician who was in a short time able to record four albums in Europe and three in New York, even before his name was mentioned in the U.S. press? That’s a question that America will have to answer, because Cleveland is only a little less guilty of squelching a major innovator in the only form of music native to America. (Ayler was also later to appear along with his brother Don in “Who’s Who”).

Albert Ayler made his first impact in Europe. While in the Army, he visited Sweden in 1962 and played a concert with two Swedish musicians who evidently had no idea what he was doing. This was released on a small private label and stood as the only recording extant until Debut Records in Copenhagen attempted to arrange a meeting between Ayler and Cecil Taylor who was appearing there with his trio. This did not happen and so Ayler was recorded with a trio of Danish musicians who, though competent, also did not understand his music. Albert was playing free and these musicians were still on a conventional track. (14) opens with Ayler’s spoken introduction (which is missing on the American release for some reason). The rhythm section plays standards but Ayler soars into another sphere.

After returning to the states he appeared sporadically in 1964 with Cecil Taylor in New York and recorded with Gary Peacock and Sonny Murray for ESP (3) and with them and Don Cherry and John Tchicai (4). All of them were playing with Cecil Taylor at the time and the latter recording was to be a soundtrack for a film which I have never seen. Earlier that year Albert had managed to record (1) with a Cleveland compatriot trumpeter, Norman Howard for Debut in a New York City studio using Henry Grimes and Earle Henderson on bass and Sonny Murray on percussion. Grimes and Henderson have an interesting duet on “Witches and Devils” (the title track) which is Howard’s composition. Leroi Jones wrote in “Downbeat” at the time that “Albert Ayler...is (getting) together...the most exciting - - even frightening - - music I have ever heard. He uses, I am told, a thick plastic reed and blows with a great deal of pressure. The sound is fantastic. It leaps at you, and actually assails you...The timbre of his horn is so broad and gritty it sometimes sounds like an electronic foghorn. But he swings and swings...”

In the fall of 1964 Ayler was able to form a quartet which included Cherry, Peacock, and Murray. They played a tour of Denmark, Sweden and Holland with a great deal of attention paid in the European press and were able to record a superb album (5) “Ghosts” for Debut. This was Ayler’s dream group utilizing three other masters of the new music besides himself. There are two versions of what came to be his theme song for the tour, “Ghosts”, and each is distinct. Cherry was quoted as feeling that “it should be our national anthem”.

A year later, Albert was able to get his own thing together in New York, and performed in two concerts in addition to sitting in with Coltrane who had taken him under his wing. “Bells” (7) was recorded at Town Hall, May Day and announced his revolutionary message to the New York musical world. His new group contained brother Don Ayler, another Clevelander Charles Tyler on alto and Lewis Worrell on bass. Sonny Murray continued to hold down the percussion chair. (Though I once saw Murray fall off his seat while furiously attacking his instruments!) This was released on an unusual one-sided, transparent disc. The next month, “The National Observer” printed a full page discussion of the New Music which contained some quotes by the Ayler brothers. Albert said: “We’re not just sitting down and trying to create beauty. We’re making more than pretty melodic forms...We’re musicians and we’re asking the whole world to listen - - and understand. We’re all together, everybody, and there has to be peace. That’s what we’re saying”. The writer (Robert Ostermann) went on to add that the Ayler brothers were “convinced that music - - their music - - can demolish the barriers and divisions between human beings. They refuse to see in their playing a simple expression of their own personal problems or those of the American Negro. ‘We aren’t selfish enough to limit it to that’ says Don.”

The Ayler Brothers, Tyler, Grimes, Peacock, and Murray again recorded for ESP (8) in September 1965 and then the first three of them returned to Cleveland where I met them in a downtown record store for the first time. In the months following I watched Albert and Don make a concerted effort to spread their musical message to their hometown. It met with modest success but the great expenditure of energy did not produce a proportional result. Ayler managed to negotiate a weekend engagement at the now-defunct “La Cave” folk club on Euclid and got the “Plain Dealer” interested enough to do a Sunday Magazine story on him. The date at the club attracted the entire Jazz community of the city, Black and White, all of whom came to get their first taste of the new sounds that had only been something to read about before this momentous occasion. Tyler rehearsed with the Aylers but left when Albert decided to add a young French violinist to the group. Michel Samson was in town to play with the Cleveland Philharmonic and was a houseguest of Peter Bergman who later became the mainstay of the “Firesign Theater”. The group also included Clyde Shy, a boyhood friend of Don on bass and Ron Jackson, a young New York percussionist. Half of (10) will give you an idea of what the group sounded like.

Several months later Ayler tried again. He organized his own concert at WHK auditorium. This time Beaver Harris joined them along with Call Cobbs on an unamplified (and nearly inaudible) harpsichord. Cobbs had once accompanied Billie Holiday in her declining days. (11) with Alan Silva (bass) and Mllford Graves (percussion) will give some indication of the sound and repertoire of this performance. Albert and Don continued to play free, but already some of the notions beginning to find favor in the avant-garde flavored their music as they began to call attention in interviews to the influence of their Black heritage. Critics exploited this kind of thinking because it lent support to the widely expressed search for Black identity.

The Aylers were pleased that they had been able to present their music to a hometown audience but were not under any illusions about being able to support themselves here by playing free. Most regularly employed musicians continued to play in the late 1950’s style of hard-bop and funk. After returning to New York Albert signed with Impulse records and completed the sides mentioned above. He then made another trip to Europe where a film was made which resulted in a couple of soundtrack recordings never released in this country. In New York, Albert continued to seek work playing his instrument and released a couple of more commercial items: two records (15 & 16), which utilized Rhythm and Blues rhythm sections beneath Albert’s unique saxophone creations. Albert had resisted this sort of thing for a long time and it was perhaps at the insistence of Bob Thiele the producer that these things were done, though it should be noted that even purist Sonny Rollins has finally succumbed to the disco beat recently. Ayler had spawned a number of imitators such as Frank Wright (also a native Cleveland musician) but whether over free rhythm or an R & B beat, Albert’s sound and ideas were unmistakable. That is why I found it both curious and shameful that the compositions on Ayler’s posthumous album (17) were credited to a woman who had been associated musically with him in his last days. The songs were clearly his. No one really knows under what circumstances Ayler died but it was probably a violent death and that was the antithesis of the man’s life which was devoted to peace and the expression of his music. Brother Don still lives in Cleveland and attempts to carry on the Ayler message, but Albert might be blowing his axe somewhere yet. It just depends on how well you listen.

Jon Goldman

It is very noticeable in these days of unlikely innovators and fleeting fashions that the two most important innovators of the last decade and a half, Ornette Coleman and Albert Ayler, are not receiving the attention they deserve. This state of affairs is abetted by both of them being woefully under-recorded, in Ornette’s case due somewhat to his expectation to be paid according to the value of his music rather than its market, while Albert was not fully appreciated by many people during his lifetime (and still is not) so that he never received the full documentation of, say, John Coltrane (let alone the maniacal overexposure of the non-underexposable Oscar Peterson). The recent ESP Disk release, “Prophecy” (2), of superb ‘new’ Albert Ayler material is therefore particularly welcome especially as it features the definitive trio of the summer of ’64 with Gary Peacock and Sonny Murray. Recorded reasonably well by the musically alert Paul Haines just four weeks before Albert’s masterpiece, “Spiritual Unity” (3), it is a timely reminder of just how superlative, how unique and how advanced this particular trio was at that particular time.

As individuals, all three contributed an incredible amount to the music. Ayler himself is once again revealed to be a master of melodic fluency, of tonal and rhythmic variety, and (unlike many others) of overall form and consistency. It is these abilities that stand out now, though at the time one tended to notice his complete break with stated time and his extensive use of properties of the saxophone that were probably not envisaged by Adolphe Sax; areas that had previously been explored in more limited fashions by Illinois Jacquet (notoriously at JATP) and John Coltrane (notably on his last great recording session before he plunged into his gargantuan cul-de-sac - the Village Vanguard date late in 1961), and which have since been extended by Peter Brotzmann and Evan Parker among others. There was also that enormous vibrato used primarily on ballads that had not been heard in any serious context for thirty or forty years, something that nobody had expected to return. Complimenting all this were the fast fragmented movements and the darting lines, involving wide jumps, of Gary Peacock, perhaps the best of the post-Mingus bassists, then at the top of his form. (He is also in such form on an exceptional unissued session that Paul Bley made for Savoy with John Gilmore and Paul Motian a few months earlier; some equally fine out takes of which have just been issued on IAI). And underneath and above and around these two was the floating percussion work of the master of implied time, Sonny Murray, whose daring approach to rhythm makes him the Thelonious Monk of the drums. Even today, Murray still imparts that unique floating feeling to his fine Untouchable Factor (while Peacock seems to be restricting himself to playing piano with a local band in Seattle).

Amazing as these three individuals are, it is the way they act together as a group that is the most outstanding feature of this trio. Ostensibly, each piece begins and ends with a theme statement (a much overused showbiz ritual) which frames a tenor saxophone improvisation (with bass and drums) and a bass improvisation (with drums). However, if one isolates each of these improvisational sections, one is left with magnificent examples of free group improvisation in which all (or both) of the musicians play an equal role with little or no hint of the conventional Jazz hierarchy of a soloist over a rhythm section. The superiority of this trio over any of Ayler’s other groups must surely be due to this aspect, which has since been explored most fully by such improvising groups as AMM and the Spontaneous Music Ensemble, both celebrating their tenth anniversaries, and the shorter lived Music Improvisation Company and Iskra 1903. (To digress slightly, it is true that Ornette Coleman defined his music as free group improvisation in his sleeve note to his “Change of the Century” Atlantic 1327, although his music usually has the format of solos over rhythm section with theme statements fore and aft, with a few notable exceptions such as towards the end of “Free” (on the s0ame record). All of which is not, of course, to put down Ornette’s remarkable achievement of creating a viable and beautiful music freed from recurring harmonic patterns, just as it would be absurd to criticise Charlie Parker for always playing over chord changes or Louis Armstrong for not playing bebop).

With one exception, Albert’s music away from these two trio records (2 & 3) seems to fall much more obviously into the solo-over-rhythm-section-with-theme-statement-frames format with occasional bursts of free group improvisation. The exception, “New York Eye and Ear Control” (4) recorded a week after “Spiritual Unity” with the addition of Don Cherry, Roswell Rudd and John Tchicai, is definitely a group improvisation but it is also a general failure (apart from some moments of joy) due to a tendency to ramble and also because each musician does not leave enough room for the others - common faults usually due to insufficient group rehearsing. Much of the time the end result is everyone soloing simultaneously instead of creating together.

Later in 1964, the trio was augmented by just Don Cherry and the resultant record, “Vibrations” (alias “Ghosts”) (5), sounds more traditional in that one is constantly aware of featured soloists and the (implied) rhythm section. This date is also more tentative due to Cherry apparently not having come completely to terms with Ayler’s area of music, a hesitancy that had been completely overcome by the time they next met on record on a generally excellent Sonny Murray date (9). Likewise, earlier on in that year, Ayler’s “Witches and Devils” (alias “Spirits”) (1) also sounds tentative due to the leader’s tendency to wander at times and to Murray not having quite found his floating feel - both of which result in occasional losses in momentum which simply do not happen on virtually all of the later records. Special attention should be paid to Norman Howard, the trumpeter on this session who has not been heard of before or since (outside of Cleveland), as he appears to have been on the verge of becoming the ideal partner for Albert. (Incidentally, I seem to remember reading somewhere that the theme “Witches and Devils” was written by Howard, which may explain why it is the only one of the four themes that he actually plays and why it does not quite sound like an Ayler theme). Having criticised these two quartet sessions (1&5), it should be pointed out that they are both superb by almost anyone else’s standards - it is just that they are not quite as good as Ayler’s own trio records. (The same cannot be said of his earlier recordings, however, which just goes to prove that his genius did not fit into earlier Jazz restrictions).

One recording that does not stand up with the trio sides is the first 1965 version of “Holy Ghost” on the otherwise dispensable “New Wave in Jazz” anthology (6). By this time Albert had found the ideal front line partner, his younger brother Don Ayler, and also a fine cellist, Joel Freedman, who occupied an ambiguous position between the front and back lines. It is these three who solo brilliantly over Lewis Worrell’s continually rumbling bass and Sonny Murray’s masterly understated drumming and eerie moaning. The second recording of “Holy Ghost” made a month later on “Bells” (7), with alto saxophonist Charles Tyler in place of Freedman, is nowhere near as good. In general, this whole half LP (7) is somewhat disappointing due to Albert being somewhat off form - the best solos being those of brother Don. Much the same can be said about the following record, “Spirits Rejoice” (8), though two of the tracks, “DC” and “Prophet”, do contain fine work by both of the brothers and by the two bassists, Henry Grimes and Gary Peacock. It is somewhat disturbing to hear Charles Tyler on these two sessions (7&8) as he then sounded very much like Albert without some of the finer attributes mentioned previously. He thus does not add anything although he plays reasonably well. It would probably be the same as hearing Sonny Stitt playing with Charlie Parker, or one of the two million (rough estimate) Coltrane imitators playing with their man himself. (As a completely irrelevant/irreverant thought, imagine all of these two million imitators playing simultaneously with, or even without, Coltrane!)

These two records (7&8) also announce the evolution into the Ayler brothers’ ‘marching’ phase wherein they devised a strangely naive yet hauntingly beautiful mixture of New Orleans marching and Hungarian Gypsy rubato with interludes of highly charged free improvisations (either solo or group). The two best examples of these are “Truth is Marching In” and “Change Has Come” both on Albert’s first Impulse LP (10). The Gypsy flavour is particularly blatant on these and on the short “Our Prayer” (on the same album) due to the presence of violinist Michel Sampson. These three performances have a beautiful feel to them alternating moments of ecstatic serenity with sections of spirited extroversion - a dangerous mixture that others have attempted without much success. The only drawback is the drumming of Beaver Harris which is somewhat too heavy and direct in contrast to that of Sonny Murray (on 7&8) and Milford Graves (on 11) which was too light and oblique for these ‘marches’. The fourth piece on the “Greenwich Village” collection (10), “For John Coltrane”, is very different, emphasizing serenity as Albert’s alto sax ecstatically intones the theme over the superb backdrop of just Joel Freeman’s cello and the basses of Alan Silva and Bill Folwell.

The next album, “Love Cry” (11), contains a somewhat similar performance in “Zion Hill” with Albert stating the theme (on tenor) over the harpsichord, bass and drums of Call Cobbs, Alan Silva and Milford Graves, resulting in some magnificent and intricate four-way interplay. This LP is also notable for “Universal Indians” which features such superlative solo and group improvisations by the two Ayler's, Silva and Graves that it must be considered one of Albert’s very best performances (even though he has some problems with a reed squeak). The remainder of the album is made up of six exquisite miniature versions of ‘marches’ and ballads whose short playing time suggests that they were tailored for disc jockeys rather than for the listening public. Incidentally, two of the tracks show, not surprisingly, that Albert’s singing reflects his playing, in the tradition of Louis Armstrong, Henry Allen and Dizzy Gillespie among others.

About Albert Ayler’s last three Impulse records and his flirtation with Rock, little need be said, except that there are precedents such as most of Louis Armstrong’s recordings after 1928, and Charlie Parker with strings (not to mention the even more bizarre Bird with voices date). But then Albert had spent his apprenticeship in R&B0 bands, so this music could not have been completely alien. (It is worth noting that similar things seemed to happen around this time to other Impulse stars such as Pharoah Sanders and Archie Shepp!). Ayler did go on to make two more albums (12 & 13) while on tour in France with a rhythm section that had nothing to do with Rock, but also had nothing to do with his music. If one can filter out the other musicians, one is left with Albert playing well by most people’s standards, but without half the invention of his earlier recordings - though it must be said that he still hovered serenely over his ballads.

These last recordings are definitely not a suitable epitaph for a remarkable but brief career whose greatest recorded achievement remains “Spiritual Unity” (3) - if only all five tracks were included in one (by no means long) album - with the ‘new’ “Prophecy” (2) and a few pieces on Freedom and Impulse as close runners up. In particular, the two trio albums capture the major stepping stone between the initial breakthrough of Ornette Coleman and the now ten years old world of free group improvisation. And these two albums should soon be augmented by another one and a half culled from the “Prophecy” session - our wildest dreams do come true sometimes.

Notes on tune titles:

The new release (2) adds to the confusion surrounding some of Ayler’s tune titles. Thus “Wizard” on (2) is the same tune as “Children” on (5), unlike the “Wizard” on (3) which is similar to “Holy, Holy” on (1) which also appears at the start of “ITT” on (4). However, “Spirits” on (2) is the same tune as that on (1) and (12), unlike “Spirits” on (3). There are actually two versions of (3) which differ only in the track called “Spirits”. The only visual clue to this difference seems to be the matrix number engraved on the second side of the record itself. If this is “ESP 1002B”, then “Spirits” is the same tune as “Vibrations” on (5), while matrix “ESPM1002 B” indicates that “Spirits” is the same tune as “Saints” on (l). It should also be noted that (7) which alleges to contain just “Bells” actually contains three pieces: “Holy Ghost”, the ballad “No Name” (which also appears on an unissued Dutch broadcast), and “Bells” itself. Finally, “Zion Hill” on (11) and “Universal Message” on (13) seem to be the same tune. Ayler often quoted from one or more of his tunes during the improvisation inspired by another, but any analysis of this would only serve to confuse matters.

Martin Davidson

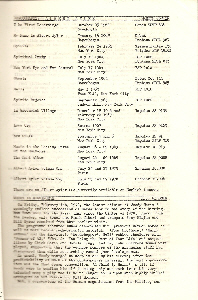

DISCOGRAPHY: This includes all of Albert Ayler’s records referred to. All sessions are under the leadership of Albert Ayler unless otherwise indicated.

(1) WITCHES AND DEVILS. Arista/Freedom 1018 (originally SPIRITS. Debut DEB146).

(2) PROPHECY. ESP Disk 3030.

(3) SPIRITUAL UNITY. ESP Disk 1002 (two versions).

(4) NEW YORK EYE AND EAR CONTROL (collective leadership). ESP Disk 1016.

(5) VIBRATIONS. Arista/Freedom 1000 (originally GHOSTS. Debut DEB144).

(6) HOLY GHOST on THE NEW WAVE IN JAZZ anthology. Impulse 90.

(7) BELLS. ESP Disk 1010.

(8) SPIRITS REJOICE. ESP Disk 1020.

(9) SONNY’S TINE NOW (SONNY MURRAY). Jihad 663.

(10) IN GREENWICH VILLAGE. Impulse 9155.

(11) LOVE CRY. Impulse 9165.

(12) NUITS DE LA FONDATION MAEGHT, Vol. 1. Shandar 10000.

(13) NUITS DE LA FONDATIO0N MAEGHT, Vol. 2. Shandar 10004.

(14) MY NAME IS ALBERT AYLER. Fantasy 86016.

(15) NEW GRASS. Impulse 9175.

(16) MUSIC IS A HEALING FORCE. Impulse 9196.

(17) LAST ALBUM. Impulse 9208.

Back to Articles main menu

*

Next: Articles 8 - De Schreeuw Van Albert Ayler

or back to Articles main menu

|

|

|

|

Home Biography Discography The Music Archives Links What’s New Site Search

|

|