|

|

|

|

|

Concerts 3:

L. S. E.

|

|

|

|

|

|

London School of Economics, 15 November 1966

Melody Maker (14 May, 1966, p. 1)

AYLER HERE IN AUTUMN?

THERE is a strong possibility that the Albert Ayler and John Coltrane groups will share a London concert later this year. Jack Higgins of the Harold Davison Agency told the MM on Monday: “I am negotiating to bring both groups in for one concert date in November. I am also trying to bring Willie The Lion Smith back for one week beginning November 16.”

*

Melody Maker (11 June, 1966, p. 1)

GETZ, COLTRANE, AYLER TV SHOWS

November concerts too?

THE John Coltrane and Albert Ayler quintets and Stan Getz’s quartet are all due in London in November to record programmes for BBC2. Negotiations are in hand to arrange a concert appearance for both quintets while they are here. And the Getz quartet will definitely play one concert. Coltrane (tnr, sop) will lead Pharoah Saunders (tnr), his wife Alice McLeod (pno), Jimmy Garrison (bass) and Rashid Ali (drs). His TV recording takes place on November 6. Tenorist Ayler’s group consists of Donald Ayler (tpt), Michael Samson (violin), Lewis Worrell (bass) and Sonny Murray (drs). They will be recording on November 15.

Astrud

Getz (tnr) leads Gary Burton (vibes), Steve Swallow (bass) and Roy Haynes (drs), and will have with him the quartet vocalist Astrud Gilberto. A concert is being arranged for them in London on November 13, and they will play for BBC2 the following day.

*

Melody Maker (25 June, 1966, p. 1)

COLTRANE TV ONLY

WHEN the John Coltrane and Albert Ayler quintets come here to record for BBC-TV in November they will not appear in any concerts. But the Stan Getz quartet and singer Astrud Gilberto are to give two concerts at London’s New Victoria on November 24. Getz and Gilberto record for BBC2 on November 14. Coltrane’s group records for BBC2 on November 6, and Ayler’s quintet on November 15.

*

Melody Maker (23 July, 1966, p. 6)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

AVANT GARDE:

ARE THERE

ENOUGH FANS FOR

CONCERT DATES?

LONDON MAX JONES

THE Albert Ayler and John Coltrane quintets and Stan Getz quartet with singer Astrud Gilberto are all visiting this country in November to record programmes for BBC TV. But only the Getz-Gilberto combination will make concert appearances (November 24).

Followers of the “new thing” on the jazz front are understandably incensed by this discrimination. Some regard it as plain reactionary prejudice on the part of those responsible for planning and putting on jazz concerts in Britain.

A reader in last week’s MM asked: “Surely there must be enough people around to make one concert a success, even if they only want to walk out from front row seats like at the Jimmy Giuffre concerts?”

He was one of several feeling “very disappointed” that there were to be no Ayler or Coltrane concerts. Are there in fact many like these? And if so, why are they not being catered for?

The simplest way to find out was to go to “those responsible”, which in nine out of ten cases means the Harold Davison Agency of Regent Street, London.

There, Jack Higgins—organiser of the concerts and club tours undertaken by American jazzmen for the agency— agreed that a few people were warm under the collar because Ayler and Coltrane were doing TV only.

“I was tackled the other night by a bloke who wanted to know why I wasn’t presenting a concert with Ayler and Coltrane. I said: ‘Well, why don’t you put them on if you’re so keen? Have you got any money? If you have, and you’re prepared to put it up, I’ll organise the concert for you.’”

But the Davison organisation is in the concert business. Why doesn’t it take the risk? “Because this is a business, not a philanthropic organisation. It is our considered opinion that such a venture would lose money.”

Okay, so what about Ornette Coleman? He toured here just recently, and people went to see him.

“Yes, but not enough. We lost money on Ornette Coleman, and other people lost money too. Let me put it this way: that concert tour was a financial failure—not a great one, a small one, but then everyone in business wants to make money.

“The trouble is, so far as I can see, that the avant-garde thing appeals to a very small minority. It’s in the minds of a few thousand jazz fans, a very few thousand at that, and they don’t make up a concert audience.

“If one specialist jazz shop sells a hundred copies of an Ornette Coleman LP it’s a big deal to them. But it still doesn’t mean there’s a concert audience for avant-garde jazz.

“People like Dave Brubeck and the Modern Jazz Quartet in the modern field, not avant-garde today, number their audiences in tens of thousands up and down the country. And this is what you have to play to every night—two thousand upwards. A man like Duke Ellington has a greater audience, of course, numbered in hundreds of thousands.”

What of Stan Getz, who is doing two concerts the same day at London’s New Victoria? “Believe me, I haven’t any doubts about Getz and Gilberto drawing. We need four thousand or just over to fill Victoria twice, and I think we’ll get them.

“We had letters in this office on the Thursday morning following publication of the news in the MM, which some people get on Wednesday, asking when tickets for Getz would be available. So they wrote to me the same night they read the news.”

What then is the answer to MM reader John Hendry’s “Surely there must be enough people around to make one concert a success?”

Higgins shook his head vehemently. “No. Obviously I’d put one on if I thought so.”

“Not even in London?”

“No, I’m afraid not. Listen . . . to put it on in London, to present it the way we do concerts, with the advertising and everything, would cost a thousand pounds before paying the artists.

“Forget about artists’ fees for a moment; it’s a thousand minimum. You need a lot of customers to get that back. And there aren’t that many.”

*

Melody Maker (15 October, 1966, p. 6)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

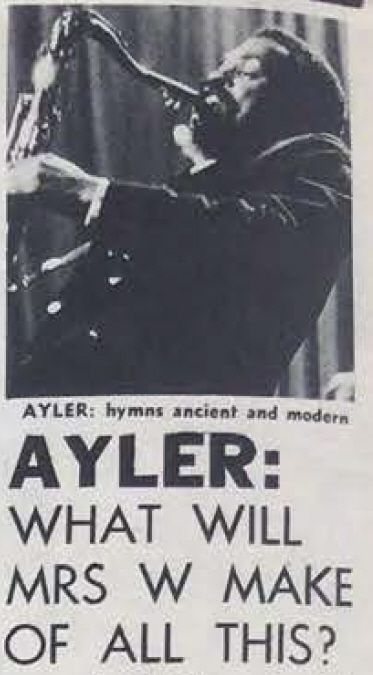

AYLER:

MYSTIC TENOR WITH A

DIRECT HOT LINE TO HEAVEN?

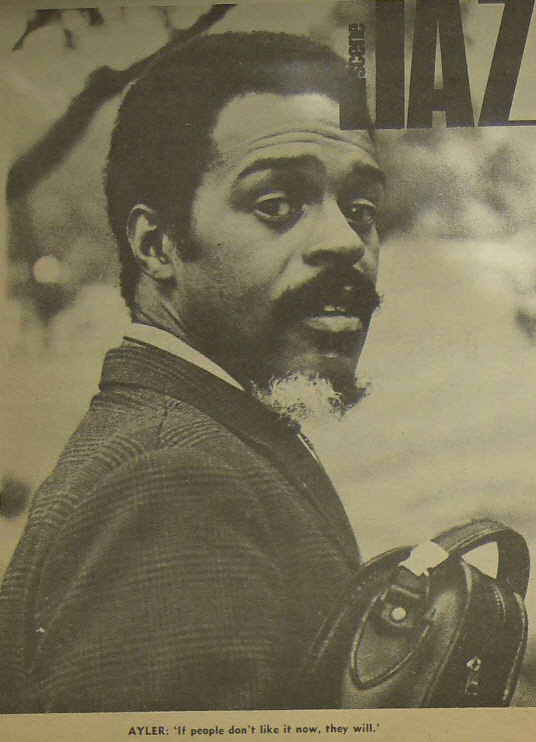

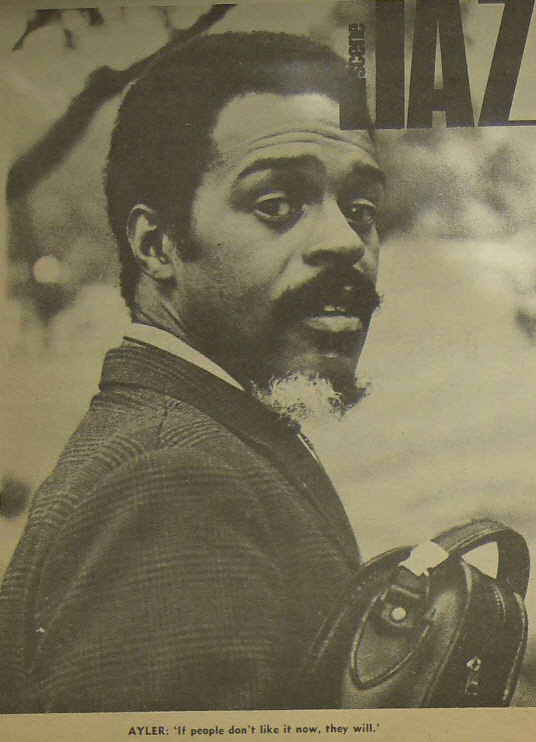

NEW YORK VALERIE WILMER

WHEN his records “Bells”, “Ghosts” and “Spirits” first hit the market with the impact of an erupting Vesuvius, Albert Ayler’s amazing tenor saxophone was variously described as being “like an electric saw buzzing” and “the ugliest sound yet to emerge from the avant garde”. Ayler, an affable 30 year old, doesn’t see it that way.

“The scream I was playing then was peace to me at that time,” he maintains. “That was the way it had to go then. Whatever was inside of me, something was happening and I did not know exactly what it was. America was going through such a big change and I’d been travelling all over, seen it all, and had to play it out of me.

_________________

SILENT SCREAM

_________________

“But now it’s peaceful. It’s more like a silent scream.”

Whether the scream is as silent as its creator claims, British TV audiences will have a chance to judge for themselves when Ayler records a programme for Jazz 625 in November.

“But,” declared the saxophonist, “If the people don’t like it now, they will. People are coming from every direction and appreciation of the truth is just a matter of time. Coltrane said it would be two years before I would be on top of the whole thing and it looks like everything is holding true.”

Ayler is supremely confident that his is the true message, yet he is far from arrogant. In fact, he and his equally easy-going trumpeter brother, Don, are two of the most relaxed and approachable musicians associated with what for want of a more appropriate term is dubbed the avant garde. It is hard to associate their calmness with the highly emotional, frantic music they make.

Little is known of the Ayler brothers who hail from a musical family in Cleveland, Ohio, and are seldom seen for long in New York. But their belief in themselves is so firm that they refuse to be intimidated by the acid waves of criticism that flow around their feet.

As infrequently as Ayler works in America, he has himself had a profound influence on one of the most respected innovators of this decade.

“After I made ‘Ghosts’ and ‘Spiritual Unity’ I sent all the records to Coltrane to help give him the direction,” blithely declared the saxophonist. “He is a spiritual brother and one that can really hear music of all different kinds. After I sent him those records, the next thing I heard was ‘Ascension’, and it was so beautiful, everything was building, everyone was screaming.”

For one so preoccupied with the idea of “screaming”, I asked Ayler to define his concept. What, for instance, are he and his fellow iconoclasts screaming about?

“We’re just screaming about life in its different channels,” was the inconclusive reply. “The true artist feels the vibrations of what he is living around and this has held true all through the past, from Louis Armstrong and Lester Young up to Coltrane. We’re not screaming against the ‘system’. A man who’s creating doesn’t have time to hate.”

Ayler smiled. “Now is the time for the artists’ artist,” he said. “Our music is a long way from entertainment music. I’d say that Archie Shepp was playing entertainment music. Whenever you hear our music you’re hearing something fresh. And that’s pure art.”

Ayler, like Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane, had a solid R&B grounding throughout the South. He spent two summers with Little Walter and his Jukes and did a further stint with Lloyd Price.

“But,” he declares, “That wasn’t for me. I had to think of a way out but it was all part of the development. It was important to my musical career to have been out there among those deep-rooted people.”

Although the saxophonist rejected conventional jazz also in order to discover his own path, he feels that his so-called “silent scream” has plenty in common with R&B.

“It’s a living feeling and most of the kids are looking for a living spirit to get their vibrations. Rock-and-roll or whatever they call it today has an exciting vibration that we have in another form.

“I always had thought of free music, even when I was still small. I’d be playing a ballad and my father would say ‘get back to the melody, stop playing that nonsense.’ But I knew there was something there. I’d be standing in a corner playing and trying to communicate with a spirit that I knew nothing about at that particular age.”

Ayler’s preoccupation with “spirits” has little to do with religion. Although raised as a Baptist he has rejected the Church for the music. “My music is the thing that keeps me alive now. I must play music that is beyond this world.

“If I can just hum my tunes and live like, say, Monk does—live a complete life like that, just humming tunes, writing tunes and being away from everything—if I could do this, it would just carry me back to where I came from.

__________

PEACE

__________

“That’s all I’m asking for in life and I don’t think you can ask for more than just to be alone and create from what God gives you. Because, you know,” he leaned forward confidingly, “I’m getting my lessons from God. I’ve been through all the other things and so I’m trying to find more and more peace all the time.”

And that is the somewhat verbose Albert Ayler. In spite of the fact that it is frequently hard to disentangle his actual meaning from the flow of words—a parallel can be drawn with the incomprehensibility of his music—the saxophonist is certainly more eager to talk than some of his associates.

But is he a mystic with a direct hot-line to heaven? Or a musical charlatan and master of the put-on? Only time, and the music, can decide.

*

The Sunday Times (20 November, 1966, p. 49)

JAZZ/DEREK JEWELL

This way out

ALBERT AYLER, determined to establish that he is without doubt the farthest out, says that Ornette Coleman, father- figure of today’s so-called jazz avant-garde, plays just dance music. Mr Ayler, in fact, plays quite a bit of that himself, sounding like straight Scotch reels. But there seems to be a general acceptance, as Humphrey Lyttelton observed at the London School of Economics last Tuesday, that among the American avant-garde Albert is the avantest.

Since Ayler’s recording for BBC TV on that day will be viewable at your friendly neighbourhood fireside, it is of some interest. Ayler’s quintet—himself on tenor saxophone, with trumpet, violin, bass and drums—would have us believe they offer new musical ideas. They do not. They are presenting old and boring ones, indifferently.

Their meandering, “total” improvisations return constantly to three basic ideas. The first is the march form, in which the quintet suggests an under-rehearsed bugle band. The second is the sentimental song, with schmaltziest vibrato from the horns—a genre akin to the foot-in-the-saloon-bar-door school of buskers. The third is sustained explosions of discord—mirroring, I don’t doubt, since I’ve read that kind of interview before, our mad, mad world.

The sheer poverty of musical ideas is the most depressing aspect of this performance, which would disintegrate utterly without the positive trumpet line of Donald Ayler. Was there then—to anticipate another part of that oft-written avant-garde interview—no pure appeal to the emotions? It moved me not at all, except towards the exit.

Happily for BBC2, another artist recorded, one day earlier, an outstanding programme for the future: Stan Getz. For those at his (untelevised) London concerts last week-end, there was some disappointment. The reasonable assumption that he and Astrud Gilberto would perform bossa nova together was unfulfilled. Miss Gilberto, with her clear, emotionless voice, sang “Corvocado” and the rest of the bossa canon adequately with her own trio. Getz’s counterpoint was much missed.

Getz himself is a more interesting musician outside the bossa umbrella. His most typical tone is unmatched in jazz tenor today: pure, soft, almost vibratoless. Yet he swings furiously, barks with the horn too, and infallibly commands the right nuance of mood, tone or phrase. His present quartet is superb. Gary Burton on vibraphone is already incredibly good at twenty-three; a touch florid, but the potential Milt Jackson of the new generation. Steve Swallow on bass is of the same class and Roy Haynes would be the perfect drummer without his twelve-minute solo.

*

Melody Maker (26 November, 1966 - p.8)

LONDON BOB HOUSTON

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE Albert Ayler Quintet's short visit to Britain last week to film for BBC2's Jazz Goes To College series was hardly an uneventful trip.

First of all, there was a bit of an altercation with the Customs at London Airport. Then there was another altercation over hotel accommodation which resulted in the five musicians spending the hours before the television show parading the streets of London, incommunicado, while BBC officials hunted high and low to find them.

But they finally made it to the London School Of Economics where small differences of opinion as to the positioning of microphones and sound balance kept the camera crew on their toes through what promises to be one of the television events of the year when Ayler and Co are projected into the lounges of the square-eyed public.

The show attracted a fair number of local musicians, including one, who shall be nameless, who confessed after it was all over: “I came to scoff, and I did.”

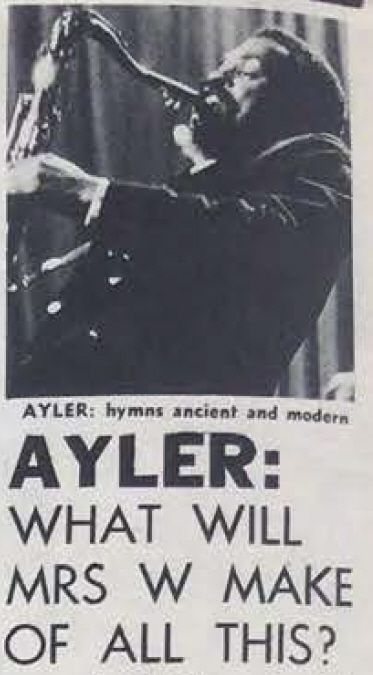

Unfortunately, the format of the two half-hour shows filmed limited the Quintet. Most of the time was taken up with the group’s unique ensemble work, a sort of Eureka Brass band sound which can be very appealing, but tends to lean rather too heavily on the march form.

Solos were cut to a minimum by avant garde standards, and what we were presented with was the Ayler musical philosophy sort of from the waist up.

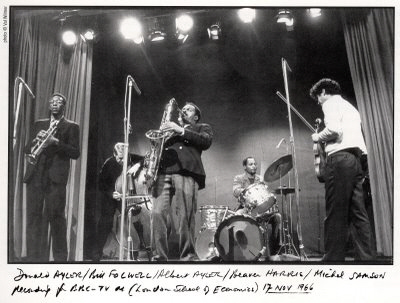

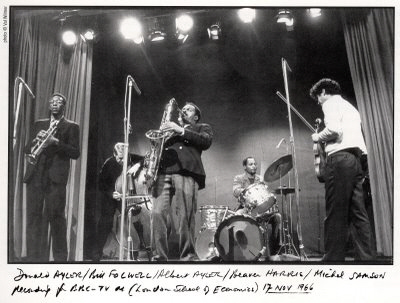

A fascinating aspect of the music played by Ayler, his brother Don (tpt), Michel Samson (vln), William Folwell (bass) and Beaver Harris (drs) Is that its melodies are mostly gleaned from folk tunes with a liberal dash of hymns ancient and modern.

Ayler has maintained that "It's not about notes any more, It's about emotions.” He plays by that credo, is faithful to it to the point where you wish at least some of It were about notes.

But one myth, the old hoary one that he can't really play the Instrument, should be settled for all time.

Nevertheless, whatever you may think, it was most encouraging to have a chance to see the Ayler Quintet in the flesh.

A hearty vote of thanks to producer Terry Henebery for bringing It all about, but I hope he's got his excuses ready when Mrs Whitehouse and her clean-up TV team find this lot blasting into their front parlours one fine evening in the not-too-distant future.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

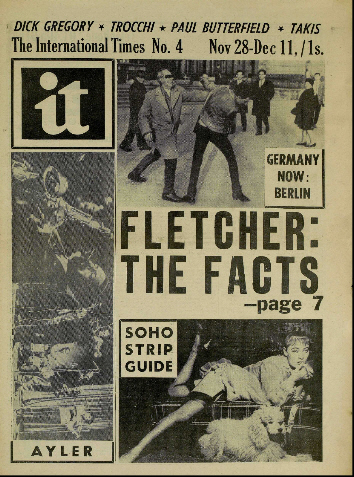

(Cover of International Times No. 4)

International Times (No. 4, Nov. 28 - Dec. 11,1966 - p.10)

AYLER AT LSE

Albert Ayler, tenor; Donald Ayler, trumpet, Michel Sampson, violin; bass: Beaver Harris, drums —

London School of Economics.

Tuesday 15th. November, BBC2’s Jazz Goes To College series.

THE music was like Ayler’s recent ESP releases — archetypal “traditional” elements (marches, dirges, hymns, reels, etc.) contrasted with “avant-garde” elements (high harmonics, other noise, non-metrical rhythms, collective playing, etc.) On record, it sometimes sounds angry, arrogant, far-off, but in person it was nothing like this, it was full of life, positive, immediately relevant. Ayler and his colleagues are trying to present an original musical experience, using “original” in its literal sense, on which antedates the institutionalisation of music, which is non-exclusive and available to everyone.

Humphrey Lyttleton’s introduction presupposed all the critical reifications the music cut through; in general, the BBC seemed to patronise the group and treat them like strange animals. It was unfortunate that this was Ayler’s only appearance, and that the group could not play before a more open audience. Some people present seemed determined not to let the music go any further into the world.—ALAN BECKETT

*

Jazz Monthly (Vol. 12, No. 11, January 1967)

Albert Ayler at L.S.E.

ON November 15th, the Albert Ayler quintet—tenor-saxophone, trumpet, violin, bass and drums—appeared before a rather baffled audience at the London School of Economics. The occasion was one of BBC-2’s “Jazz goes to college” series, and the event should presumably hit the TV screen in the near future. The BBC are showing commendable initiative in this series (only recently, Sonny Rollins and Max Roach taped a similar concert), so one must cross fingers and hope that Ayler’s group has not scared them off.

Each item performed followed a basic pattern. The front-line played a succession of themes, each introduced by Albert Ayler; then, perhaps, a round of brief solos and finally a partial recapitulation. The nature of the themes and their interpretation can only be compared to a New Orleans band, in particular to the marches and dirges of a brass band of the Eureka type.

In his lead work (to use the traditional terminology), Donald Ayler asserted himself more convincingly than on record. His tone—not so coarse as expected but still closer to that of a parade trumpeter than to anyone else—completely lacks the declamatory brilliance and rich vibrato of the post-Armstrong era. Likewise his brother’s sound, even down to the quavering vibrato, resembles that of the Eureka’s Manuel Paul. The violin took on the clarinet’s role, weaving around and above the other two. These ensemble passages were generally kept within the New Orleans harmonic idiom, though with dissonant moments which naturally reflected the sophisticated musicianship of the 1960s. Against this strict counterpoint, the rhythm section ignored metric considerations entirely. William Folwell retained his bow for the whole evening, sawing furiously away to provide a background of swirling colours. Drummer Beaver Harris added the rhythmic colouring, skimming over his kit in the manner of Elvin Jones and following the shifting dynamics with minute precision—but without Jones’s overall allegiance to a regular beat.

Who could have foretold this New Orleans revival, nearly twenty-five years after Bunk Johnson acquired his new teeth? That it has not occurred accidentally is proved by an interview with the brothers published in the Down Beat of November 17th. So far this concept is confined to one group, though the idea of building a composition around several themes on a cue from the leader is also adopted by Don Cherry (cf. Blue Note BLP 4226). In their latest work, both Cherry and Tyler relegate the solo statement to a minor position in favour of collective interplay—the familiar New Orleans’ allocation of priorities.

The solos of the Ayler brothers cannot possibly be judged by the standards of Armstrong, Ornette Coleman or even of the Albert Ayler of earlier LPs. Now there is absolutely no attempt at the merest kind of structure; what they play is unmitigated, relentless noise. Compared with the function of the bass and drums, the solos provide the emotional colouring—violent and often hysterical—to contrast with the sobriety of the thematic material.

Certainly the reception was mixed. Some hated the music; some thought it limited. Those who reject anything faintly different dismissed the group out of hand. In a complementary gesture, some who respond exclusively to the latest sounds (until later ones come along) were disappointed: after all, they had not gone to the L.S.E. just to hear a Trad. band. Myself, I loved it; but then I always have had a weakness for such bands as the Eureka. And make no mistake, the ensemble playing is everything one could wish for: clean, well-integrated and with untold imaginative touches. The relationship between melody and rhythm fascinates and, of course, is quite revolutionary. Here I must mention the violinist, Michael Sampson. Those who have heard Coleman will recognise the astringent approach, but Sampson has a stronger orthodox technique. In addition, he took the one solo of the evening that developed a theme used by the ensemble.

Limitations are obvious: the lack of melodic variety and, surprisingly, the lack of adventure, of reaching into the unknown. The truth is that here is an instance of musical innovators suddenly stumbling upon a self-contained form. Nothing however can mask the present validity of their music. Ayler now needs to expand, and there is every reason to suppose that he will. Prophecy is usually pointless, but in time perhaps the ensembles will become freer—more like one of the old Albert Ayler solos—and the dichotomy between style and solo will dissolve into a total sound where melody, solo, rhythm, noise all interact.

RONALD ATKINS

*

International Times (No. 6, Jan 16 - Jan. 29, 1967 - p.15)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

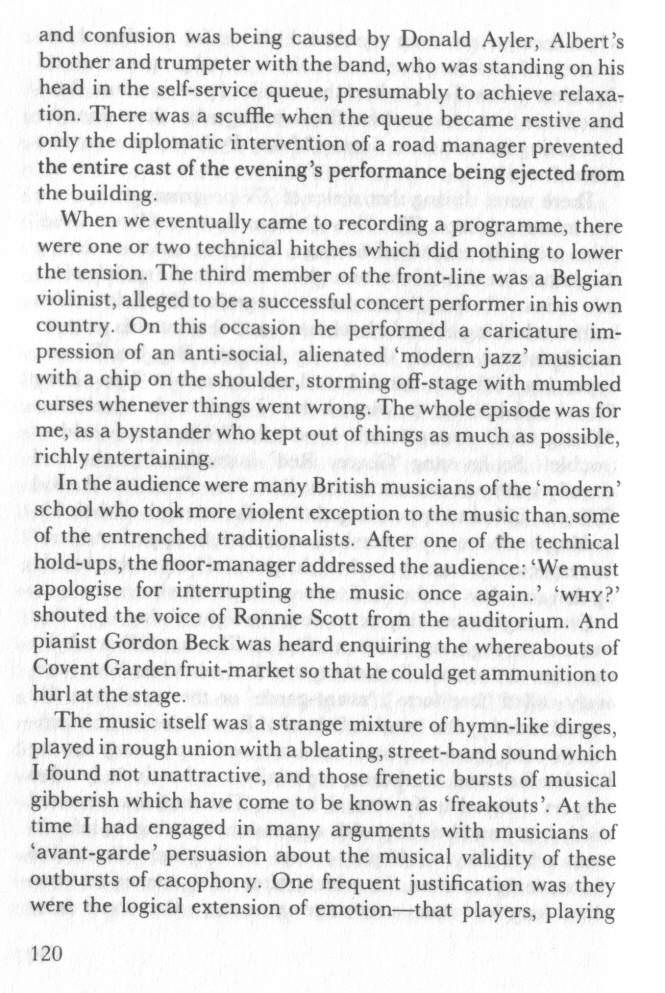

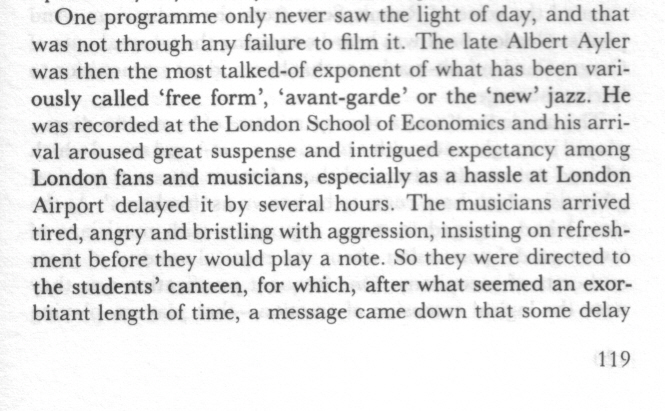

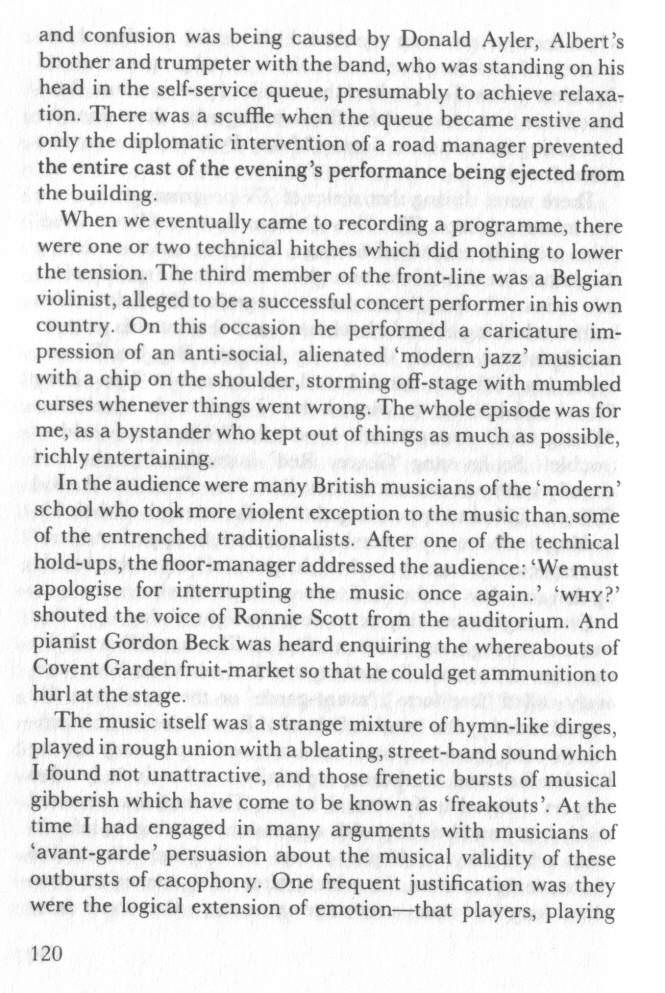

The BBC were scared off by Albert Ayler, refused to broadcast the concert and later destroyed the tape. Humphrey Lyttelton, who introduced the programmes in the Jazz Goes to College series, later recalled the Ayler concert at the L.S.E. in his book, Take It From The Top (London: Robson Books, 1975):

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Humphrey Lyttelton was interviewed by Richard Cook in the May, 2001 issue of Jazz Review (No. 20, pp.24-27) and touched on Ayler’s L.S.E. concert. I have to thank Sean Wilkie for letting me know about this and for transcribing the relevant section (with an introductory note):

[Richard Cook is interviewing Humphrey Lyttelton and after talking about his first recordings, his move to Parlophone, his accidental hit with Bad Penny Blues and its ‘influence’ on The Beatles, they muse about the split between traditional jazz and popular music. Humph thinks that jazz is unique in western culture for appealing simultaneously to the brain as well as to the heart and feet. In response to Lester Young, he imagines, some will dance, some will go ‘ohhh, did you hear that?’ and some will be thinking about his linear improvisation: “All at the same time”. (pp.26-27)

The (immediately) following is all from p.27.]

[RC]: Having been witness to so much of it, is he optimistic that jazz will carry on?

HL: “I’m encouraged to be optimistic about it, because from observing it through the years … it’s like a worm. If you put a spade through a worm, the two halves continue in their own way. Jazz has a capacity to appear, at the sharp end, to appear to be heading for the rocks. If you take the avant-garde of the 60s, the freak-out end, it occurred to me at the time that the other quality of jazz, of everyone having their own voice – once you get to extended screaming at the upper end of the harmonic range, how can you tell one person screaming from another? And after you’ve screamed, where do you go from there? In the modern music now, one of the most dated elements today is the freak-out. I was listening to Tubby Hayes’ 100 Per Cent Proof album, a roaring big band thing – and for no apparent reason there’s a huge section where the big band is just freaking out, as if it was something you had to do then. When I was introducing BBC Jazz Club, if there was a band like, dare I say, Tony Oxley’s or John Stevens’, I’d sneak round and look at the music, and it was all things like electrical circuits and drawn symbols, but quite often you’d see a little section in the circuit which said “freak out”.

“I introduced Albert Ayler’s band at the LSE for a BBC recording. An odd occasion altogether, very strange, but it’s a pity the BBC didn’t show it. There was a thing about his band then which I sometimes thought was assumed … a sort of aggression and anger. The violin player, a Belgian classical violinist, he was the nearest to a complete caricature. He walked on stage swearing and he walked off stage swearing. It created an atmosphere where the producer, Terry Henebery, appeared to be going into the jaws of death if he asked them for anything. He wanted them to do two minutes fore and aft for the credits to run under, and when Albert finished his set – Ronnie Scott and Roland Kirk were there watching and their comments were interesting - Terry asked them to do another two minutes, and Albert went on objecting to it, and eventually he turned to the band, and said, OK, for two minutes we go crazy. And they did two minutes of madness. I thought then, well … emotion didn’t have much to do with it. But a lot of that stuff I’ve taken on board, or at least I don’t reject it out of hand. It’s difficult for someone with my background in music to get drawn into it, but I listen to a lot of contemporary things.”

[Then the discussion moves back to Humph’s own playing and music.]

*

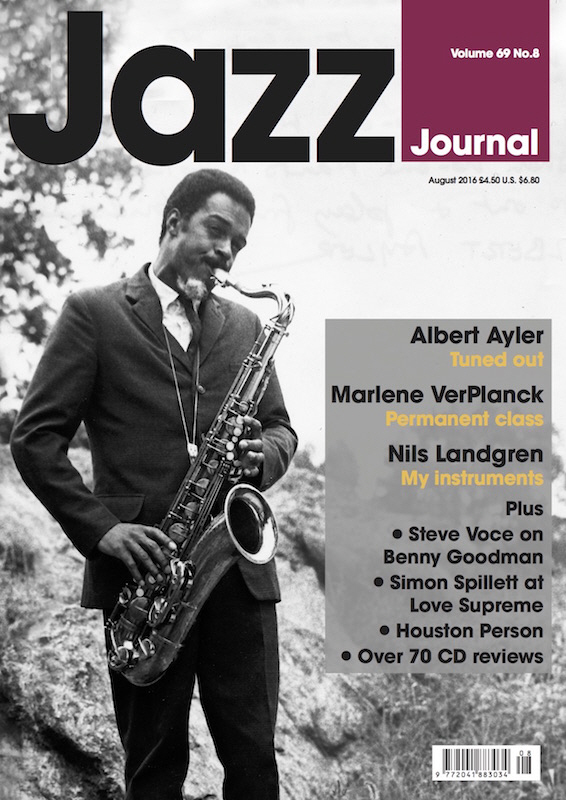

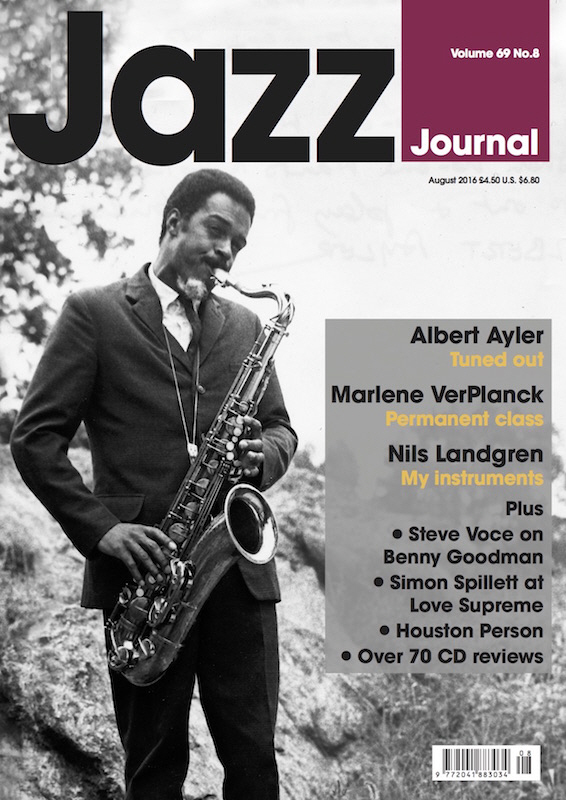

Fifty years later Ronald Atkins returned to the subject in the August, 2016 edition of Jazz Journal, which had Albert Ayler on its cover.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Also from 2016 is an interesting article by Robin Kidson on the Sandy Brown Jazz site.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

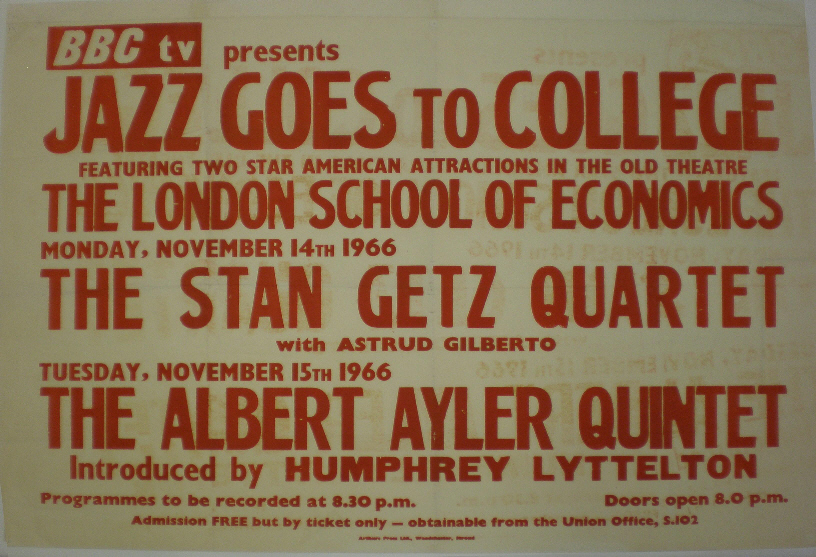

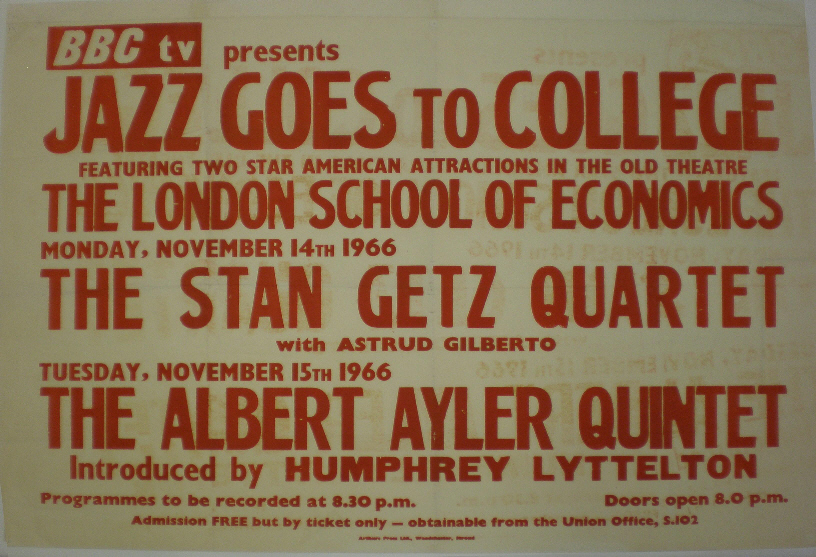

[Poster for the L.S.E. concert.]

[See also the Ayler Remembered section.]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

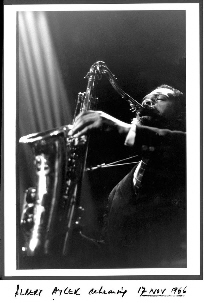

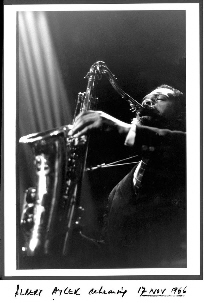

© Val Wilmer

In August, 2021, Dave Jackson pointed me in the direction of ‘Unholy Ghosts - conspiracy theories and Albert Ayler’ by Eddie Prévost, an additional chapter to his book, An Uncommon Music For The Common Man, which suggests that the L.S.E. concert was never recorded at all, the cameras were turned off during the performance. The chapter is available as a free pdf download from Matchless Recordings.

Next: Cleveland, 4 February 1967

|

|