|

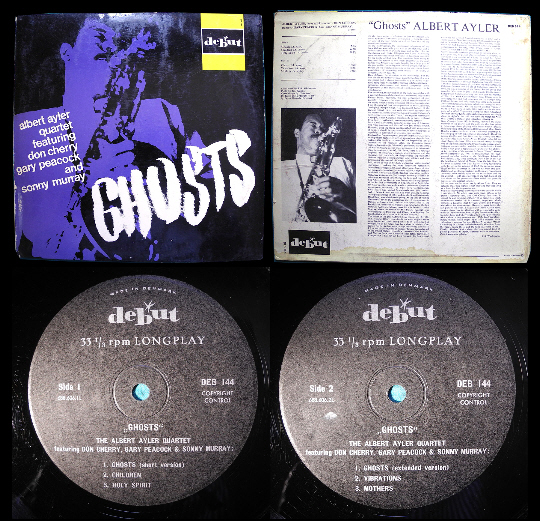

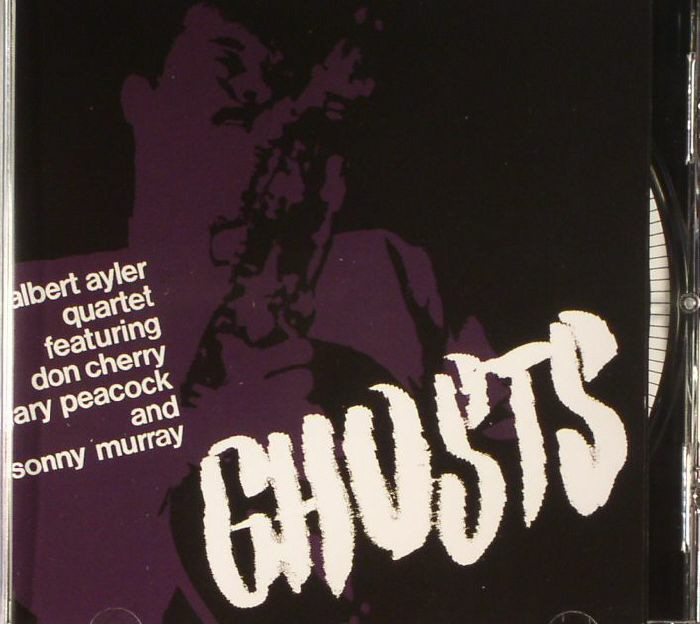

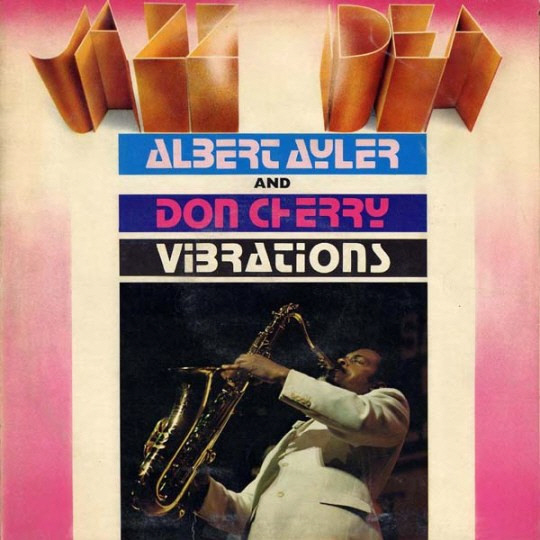

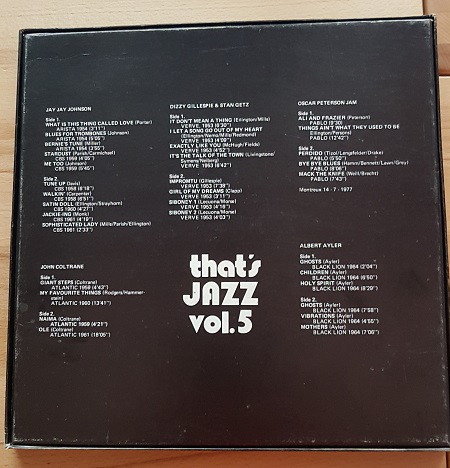

Sleevenotes of DEB144:

Of the three major revolutions in jazz the present one seems to be by far the most demanding—from the point of view of the jazz public as well as from that of the musicians themselves.

In the mid-twenties, the improvised polyphony of the New Orleans ensemble gave way to an orchestral and a solistic conception of playing jazz, and neither Fletcher Henderson and Duke Ellington nor Louis Armstrong seem to have had much difficulty in becoming accepted by the public of that time. The transition from swing to bop and the return to the small ensemble in the mid-forties was certainly met with hostility by a large part of the jazz public (including most of the critics), but nevertheless all the leading musicians in the movement found possibilities of presenting their music—in clubs, at concerts, and on records.

How different the situation in the mid-sixties. For the first time in the history of jazz, even the leaders of a new movement find it almost impossible to gain public exposure, being faced with a rather massive indifference from American club-owners and record companies alike. Regrettable as this may seem, it is not, in a way, to be wondered at.

For one thing, the revolution of the sixties coincides with a general slump in club attendance and record sale in the United States. Secondly, the new conception of jazz probably represents the most radical transformation of the music which we have witnessed till now. In particular, I am thinking of that decomposition of the traditional, “swinging” tempo which is a prominent feature of the present record. Here, not only the chord sequence and the measure are done away with, as on Ornette Coleman’s later records—even that “beat,” the regular marking of a tempo, which Coleman maintained, is being replaced by a purely rhythmical, non-metronomic texture.

Such a music evidently demands a new way of listening, free from preconceived ideas of how jazz should sound. However, once the music is approached with an openness of mind, it should be apparent that, in several respects, it represents a cultivation of essential jazz qualities.

The freedom from composed, pre-existing material, always an important feature of jazz, is carried one step further, making this music even more of an improvised art, a creation of the moment. Also, the liberation from metrical limitations in favour of a predominantly rhythmical way of playing is even more pronounced in this music than in previous styles of jazz. Then, there is a renewed emphasis on collective creation, which integrates all the musicians into the whole, to a large degree suspending the division between accompaniment and soloists and thus diminishing the role of the single soloist.

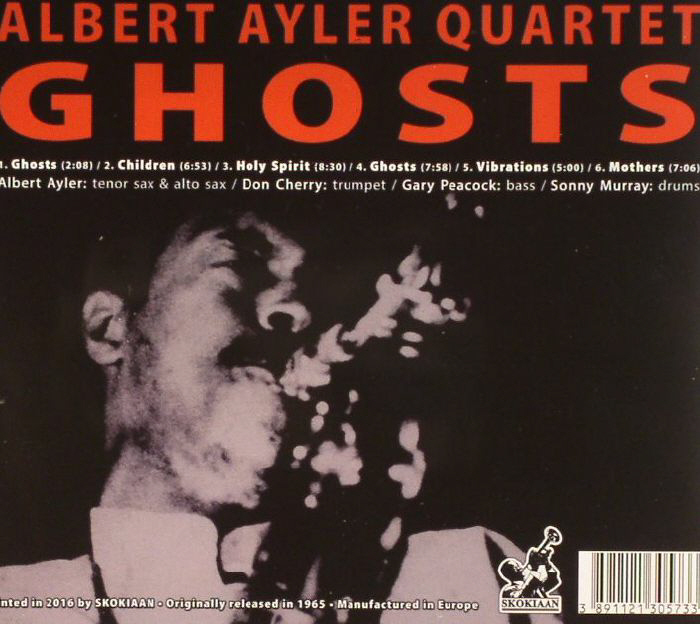

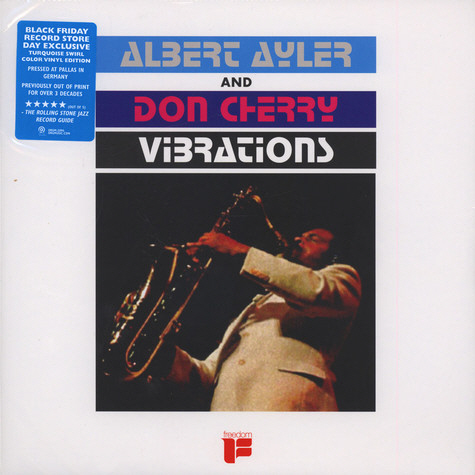

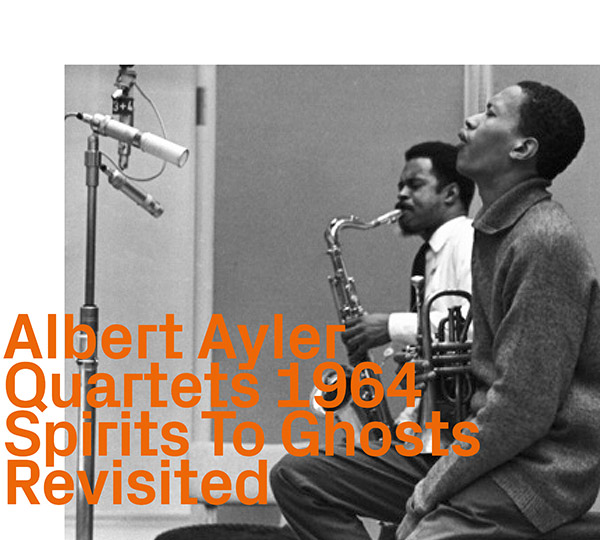

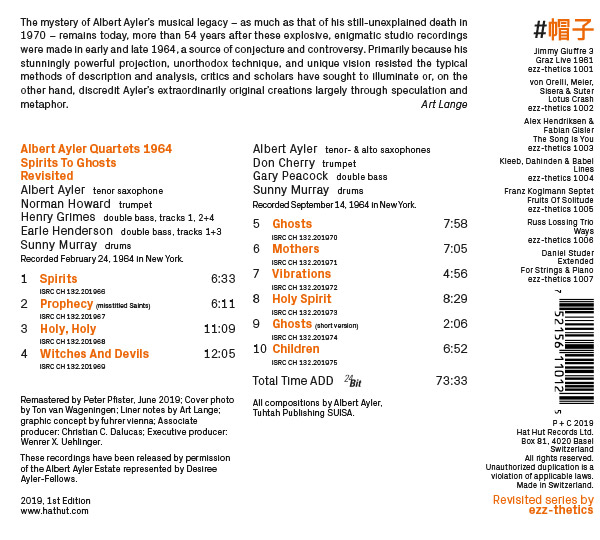

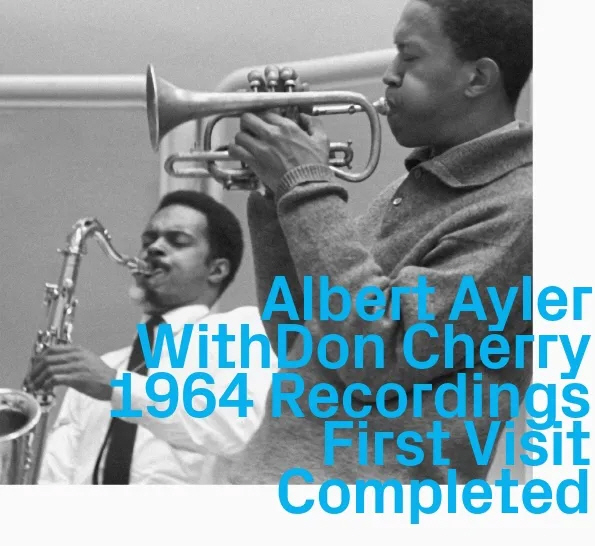

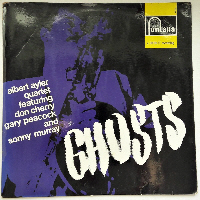

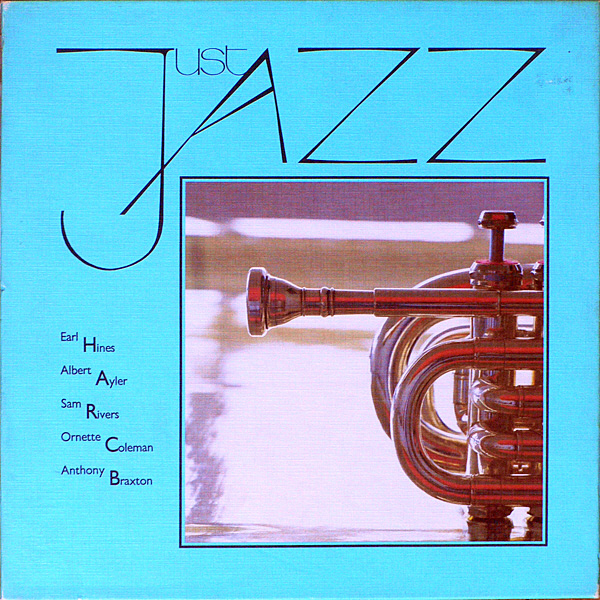

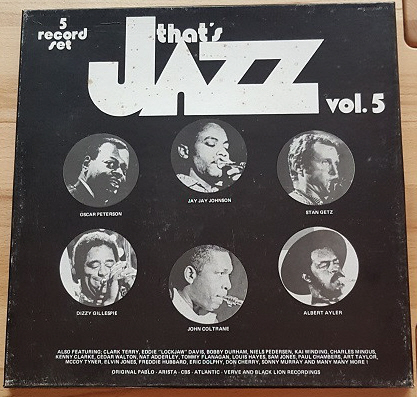

Still, there is the individual, expressive utilisation of instruments, making the more important performers immediately recognisable, as in all previous forms of jazz. All this can be heard on the present record, which features musicians who are among the leading innovators on their respective instruments: the trumpet (actually a cornet in this case), the tenor saxophone, the bass, and the drums. The Albert Ayler Quartet was formed for an engagement at the Jazzhus Montmartre in Copenhagen in September 1964, as was the case with another prominent American avant-garde ensemble, The New York Contemporary Five, which had visited Scandinavia one year earlier. Ayler, Peacock and Murray had been playing together during the summer of 1964, and for the Scandinavian trip Don Cherry was added to the group. At the time of writing (December, 1964), the quartet had played engagements in Denmark, Sweden and Holland (an appearance at the Polish Jazz Jamboree in Warsaw was canceled at the last minute): Ayler and Murray were back in Denmark, with Murray about to return to the States, Peacock was convalescing in Belgium, and Cherry was heading for North Africa after visits to Paris and London.

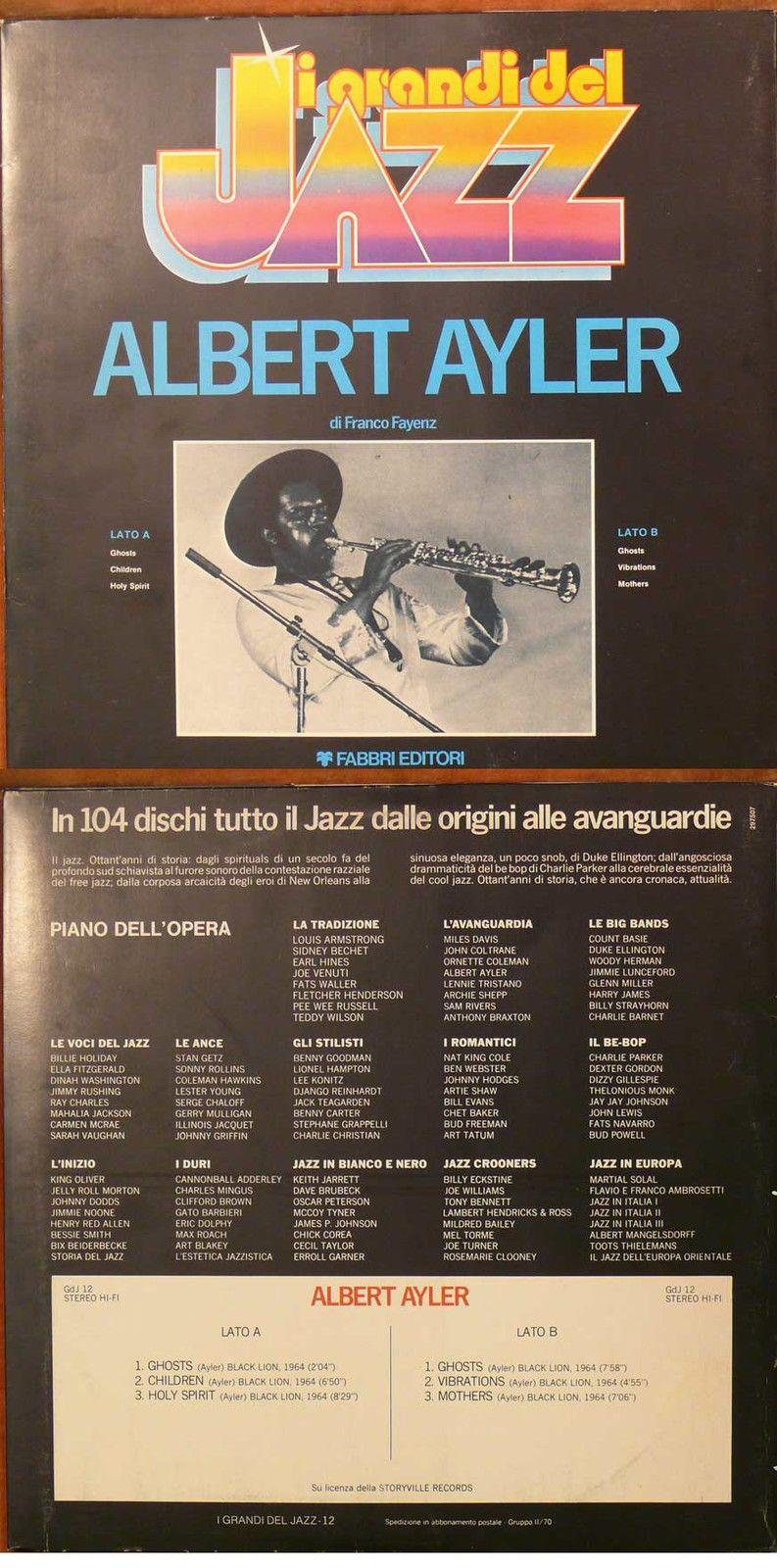

The leader of the group, Albert Ayler (born July 13, 1936, in Cleveland, Ohio), is probably the most original tenor saxophonist to come along since John Coltrane, but recognition of his talent has been slow in coming. One reason for this is that, even though this record is the fifth LP he has recorded, none of his records have been released in the United States. He made a trio record with Peacock and Murray for a new American label before leaving for Europe, but it has not yet been released; his first record was made for a small Swedish company in 1962, and a record made in New York in early 1964 has only been put out in Denmark by Debut Records. Thus, his only record which has had European distribution is the one made in Copenhagen in January, 1963 (“My name is Albert Ayler”, Debut DEB140/Fontana 688603ZL).

Ayler’s musical experience goes back to the time when, as a ten year old, he played alto saxophone at funerals in Cleveland as a member of a band in which his father played the tenor saxophone. Later, he used to perform at a music-hall in his hometown, and when he was sixteen, he was on the road for four months with a rhythm & blues band led by harmonica player Little Walter Jacobs. Around 1956, he switched to tenor and since 1962 he has been associated with Cecil Taylor, appearing with Taylor’s trio in Scandinavia in the autumn of 1962 and at a concert in Philharmonic Hall on New Year’s Eve, 1963.

Of the four musicians on this record, cornetist Don Cherry (born November 18, 1936, in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma) is the best known, having played with the original Ornette Coleman Quartet and on all of Coleman’s records. In 1962, he was a member of the Sonny Rollins group that recorded “Our man in jazz” and in early 1963 he toured Europe with Rollins, returning later that year as a member of The New York Contemporary Five. Cherry may be considered the first real innovator on the trumpet since Clifford Brown, and this record has some quite remarkable contributions from him, which are among his most articulate on record. On the record entitled “Spirits,” made in New York in early 1964, Ayler was in the company of a gifted 22-year-old trumpeter from Cleveland, Norman Howard, whose musical conception is amazingly close to Ayler’s, but still not quite the match for Ayler that Cherry’s mature and individual playing is.

Gary Peacock (born 1935 in Butley, Idaho) is the oldest member of the quartet and the only one that has gained a reputation from playing with better-known groups, including those of Bud Shank, Bill Evans and Miles Davis. Besides working in these rather traditional ensembles he has also played with experimental groups led by Don Ellis, Jimmy Giuffre and Paul Bley, and he actually left Miles Davis to play with Albert Ayler. Peacock, who did not start playing the bass till he was around twenty, is today one of the most accomplished bass players in jazz, a truly virtuoso instrumentalist, and this record is the first I have heard which gives a representative picture of his ability.

A key member of the quartet is James “Sonny” Murray (born September 21, 1937 in Philadelphia). His background includes studies at the Schillinger School in Philadelphia and, since coming to New York in 1955, at the Manhattan School of Music. Since the late fifties, he has been associated with Cecil Taylor, visiting Scandinavia with Taylor in the autumn of 1962. He is, to my knowledge, the first drummer in jazz who has been able completely to discard time-marking, and he is a very economic drummer, who mainly relies on the snare drum and the top cymbal—with spare accents on the high-hat and the bass drum—for percussive effects which are generally kept at a very discreet volume.

All the tunes on the record are by Albert Ayler. They are actually more like signals which may and may not serve as a basis for the improvisation.

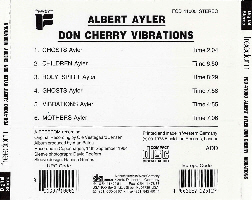

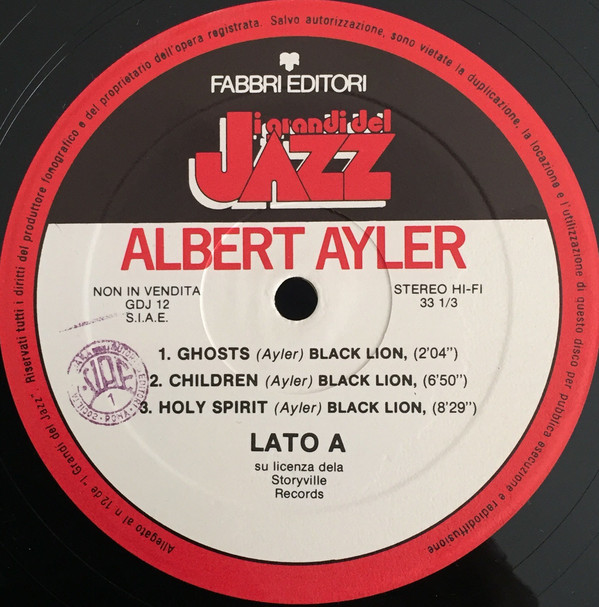

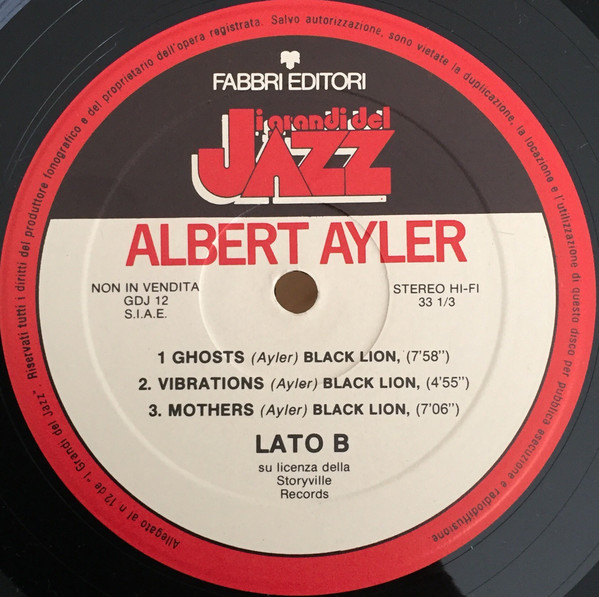

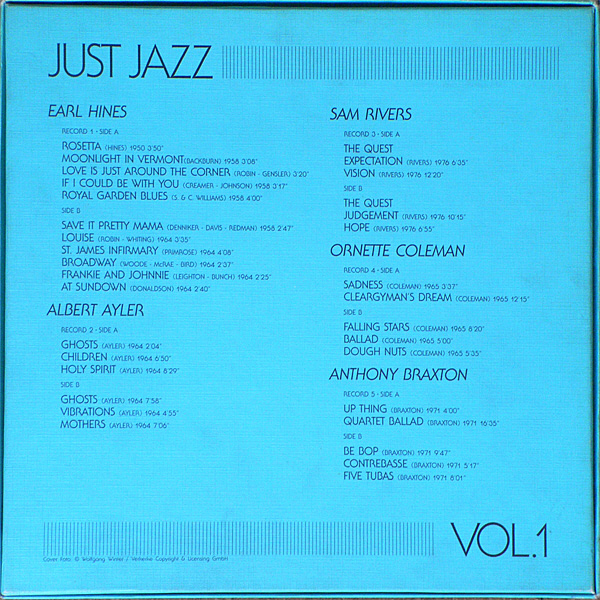

The music is presented on the record in the order in which it was played. No other takes were made. Ghosts is the group’s signature tune, and Don Cherry feels that “it should be our national anthem.” It is heard in a short, introductory version and in a second, longer one, which contains a beautiful duet between Cherry and Peacock and where, for some reason, Murray lays out during the last part of the track. Children also shows Ayler’s tenor ranging from roar to whistling with a remarkable command of the instrument, Peacock gets flamenço-like effects from his bass, and Cherry puts a stop to the performance with a clear, strong punctuation. Holy Spirit is a slow, stately theme, which might be fit for a funeral, while Vibrations is another fast one. Of this, Ayler says: “When I was living in Harlem, I felt the beautiful vibrations from the people living there, and the tune just came to me.” Finally, Mothers, which shows the very special kind of pathos particular to Ayler, expressed with an enormous, almost grotesque vibrato.

Erik Wiedemann

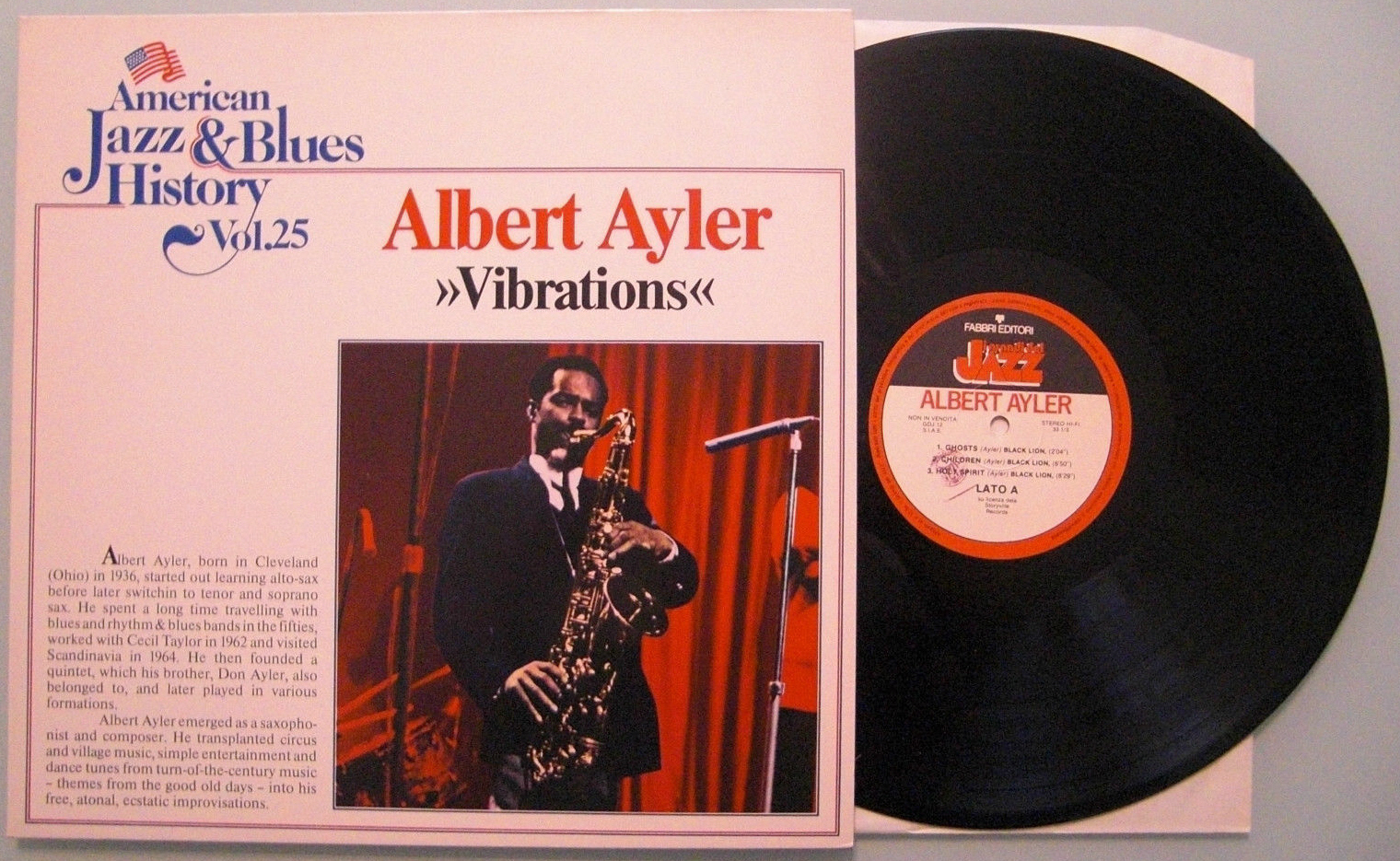

Fontana (Netherlands) 688.606ZL

|