|

Town Hall, New York, 1 May 1965

Down Beat (Vol. 32, No. 15, 15 July, 1965, p. 12)

CAUGHT IN THE ACT

Reviews Of In-Person Performances

Bud Powell / Byron Allen /

Albert Ayler / Giuseppi Logan

Town Hall, New York City

Personnel: Powell, piano. Eddie Gales, trumpet; Allen, alto saxophone; Walter Booker, Larry Ridley, basses; Clarence Stroman, drums. Don Ayler, trumpet; Charles Tyler, alto saxophone; Albert Ayler, tenor saxophone; Louis Worrell, bass; Sonny Murray, drums. Logan, bass clarinet, flute; Don Pullen, piano; Reggie Johnson, bass; Milford Graves, drums, percussion.

_____

To the supporters of the jazz avant-garde—musicians, critics, and fans—there seems to be no middle ground. One is either for or against the new music, and any expression of reservations is interpreted, in the manner of political or religious movements, as a species of treason.

Furthermore, the insistence of those supporting the avant-gardists that the music is a socio-political act, and their habit of attacking even sympathetic criticism with such semantic bludgeons as “racial prejudices,” “backwardness,” “white power structure,” and other ideological catch phrases of dubious relevance, hardly has served a climate of reasoned objectivity.

To this reviewer—and let the chips fall where they may from assorted shoulders—the sole relevant issue is the validity of the new music as music, at least within the confines of a review such as this.

To agree that there is room in jazz for radical innovation is not synonymous with the abandonment of all prior esthetic standards, and to be sympathetic to new things in jazz does not mean that all that is new must be received with unqualified approval simply because it is new.

This concert presented, in addition to an honored jazz veteran, three groups of widely varying quality and orientation, having little in common beyond their affiliation with ESP Disks, a newly founded record company that presented (and, in part, recorded) the event.

Alto saxophonist Allen’s group, which opened with a 25-minute set devoted to one piece, is rooted in Ornette Coleman’s approach to jazz. Allen employs some of Coleman’s speechlike phrases and some of his rhythmic and melodic patterns, but he does not as yet have a comparable sense of form and organization. A lyrical, rather gentle player, he still has to learn to edit himself, and his music now makes a rather unformed and tentative impression.

Allen’s rhythm section, despite the presence of two bassists, was fairly conventional; i.e., it swung. Ridley, a fine player not exclusively affiliated with the avant-garde, and Stroman, who also is primarily a modern-mainstream player, took good care of the timekeeping, while Booker played fills.

Powell followed, playing solo piano. Though in considerably better form than at his distressing appearance at the Charlie Parker Memorial Concert at Carnegie Hall in March, Powell was far from his peak. However, his final selection, I Remember Clifford, was extremely moving, and what had seemed to be faltering time on the faster pieces now became a nearly Monkish deliberateness, each phrase ringing out full and strong. What Powell hasn’t lost is his marvelous touch and sound, and everything he played revealed a sense of balance and proportion not much in evidence elsewhere on the program.

Next came Logan, a multi-instrumentalist who restricted himself to a mere two of the nine horns this reviewer has so far heard him play.

Of his two compositions, the first featured him on flute, which he plays with an attractive tone but a technique far from virtuosic.

Percussionist Graves was much in evidence, opening the proceedings on an array of instruments including a large gong, bells, gourds, rattles, and African types of drums. For the second part of the piece, Graves switched to a regular set of drums. Straight time is not his forte; he uses percussion to embellish and punctuate, setting up a continuous barrage of sound, which can be striking when it does not overwhelm the efforts of the other players.

The second piece featured Logan’s bass clarinet. The sounds he produced—shrieks, swoops, and gargles—brought to mind Eric Dolphy at his most extreme but lacked the latter’s technical brilliance, emotional force, and sense of contrast. With this kind of playing, it is sometimes hard to decide which notes are voluntary and which are accidental.

In spite of his occasional wildness, Logan appears to be a musical eclectic with romantic leanings and a flair for melodic invention that he might profitably explore. In addition, his music has a kind of theatricality (both he and Graves are “showmen” of a sort), and he could become the first popularizer of avant-garde music, or rather, its surface characteristics.

Bassist Johnson was often inaudible (through no fault of his own) but was effective in a duet between arco bass and percussion, during which Graves bent and twisted a cymbal while beating it with a mallet.

Pianist Pullen is a technician with great dexterity, but his improvisations are those of a classically oriented musician—chromatic runs (not unlike a random medley of Scriabin fragments) without a trace of swing or rhythmic definition.

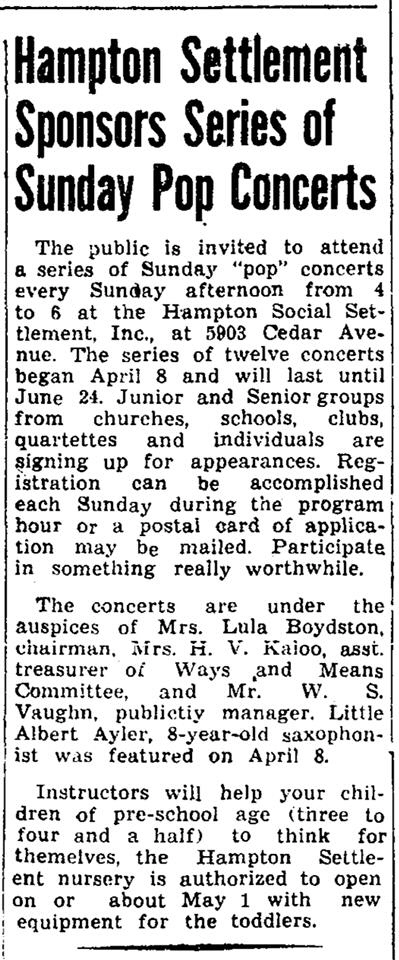

The concert concluded with by far the strongest and most unusual music of the afternoon. Albert Ayler is certainly original. His tenor saxophone sound, on fast tempos, is harsh and guttural, with a pronounced vibrato and a multitude of what used to be called freak effects in King Oliver’s day. He plays with a vehemence that startles the listener, either repelling him or pulling him into the music with almost brute force. The effect can be oddly exhilarating.

On slow tempos, Ayler favors a vibrato so wide that it brings to mind Charlie Barnet’s old take-off on Freddy Martin. It is an archaic sound, and the phrasing that goes with it—drawn-out notes, glissandi, sentimental melodic emphasis—is quite in keeping.

Trumpeter Don Ayler plays like his brother plays fast tenor: loud, staccato, and broadly emphatic. But his fingering technique appears elementary. He did not solo at slow tempo. Altoist Tyler fits the brothers. His sound is not unlike Albert’s but more grating and less controlled—some of his overtones were involuntary, whereas the tenorist meant every note he played to be.

The music that goes with this definitive instrumental approach is no less personal. It resembles at times—in texture as well as voicings and melody—the music of a village brass band or a military drum-and-bugle corps. In spite of its abrasiveness, the music is quite gay and friendly—“country” might be the word for it. The harmonies are stark and almost primitive, with occasional forays into bagpipe effects.

Ayler’s group played two pieces. The first, quite brief, ended with a prolonged bombardment by the full ensemble; a flurry of repeated notes played strictly on the beat. The effect was not unlike a surrealistic parody of those famous Jazz at the Philharmonic finales, replete with screaming trumpet and honking saxophones. Or perhaps the image was of a rhythm-and-blues band gone berserk.

The second piece, though sprawling and too long, was nevertheless filled with exciting passages. A slow tenor solo was followed by a bass interlude and then a call to arms by the horns, a militaristic theme-statement, a fast tenor solo, ensemble interlude, solos by all the horns at very rapid tempo, a return to the theme, another call to arms, and a bansheelike concluding ensemble.

The horns—the leader especially—played with such rhythmic thrust that the role of the rhythm section was merely incidental. Murray seemed forever to be trying to catch up with the horns. Worrell was effective in solo, and his backing of Ayler’s slow improvisations was particularly apt.

To this listener, there seems to be a great deal of wild humor in Ayler’s music. Though often vehement, it is celebration rather than protest; much of it has the sheer “bad boy” joy of making sounds.

Whatever one’s reaction to this music, there can be little doubt that it contained the spirit of jazz. Some may dismiss it as untutored, primitive, or merely grotesque, but it certainly has the courage of its convictions and is anything but boring or pretentious.

If one thing was made clear by this concert, it is that the so-called new thing is really many things: very different approaches to innovation (or novelty?) in jazz, having in common only a predilection for radical means of expression. If there is a jazz revolution, it has already developed its Bolsheviks, Mensheviks, Social Revolutionaries, and Trotskyites (I don’t know of any musical Stalinists) and is definitely not a unilateral phenomenon. At its core, as always in jazz, lies the personal and individual.

Perhaps it is time to get away from the emphasis on categories and get back to the proper perspective—the individual one—which would eliminate the pointless and absurd debates about “modern” and “old-fashioned” music.

—Dan Morgenstern

*

The following edited extract from this review was used as the sleevenotes to Bells:

Albert Ayler is certainly original. His tenor saxophone sound, on fast tempos, is harsh and guttural, with a pronounced vibrato and a multitude of what used to be called freak effects in King Oliver’s day. He plays with a vehemence that startles the listener, either repelling him or pulling him into the music with almost brute force. The effect can be oddly exhilarating.

On slow tempos, Ayler favors a vibrato so wide that it brings to mind Charlie Barnet’s old take-off on Freddy Martin. It is an archaic sound, and the phrasing that goes with it—drawn-out notes, glissandi, sentimental melodic emphasis—is quite in keeping.

Trumpeter Don Ayler plays like his brother plays fast tenor: loud, staccato, and broadly emphatic. .... He did not solo at slow tempo. Altoist Tyler fits the brothers. His sound is not unlike Albert’s but more grating and less controlled—some of his overtones were involuntary, whereas the tenorist meant every note he played to be.

The music that goes with this definitive instrumental approach is no less personal. It resembles at times—in texture as well as voicings and melody—the music of a village brass band or a military drum-and-bugle corps. In spite of its abrasiveness, the music is quite gay and friendly—”country” might be the word for it. The harmonies are stark and almost primitive, with occasional forays into bagpipe effects.

Ayler’s group played two pieces.The first, quite brief, ended with a prolonged bombardment by the full ensemble; a flurry of repeated notes played strictly on the beat. The effect was not unlike a surrealistic parody of those famous Jazz at the Philharmonic finales, replete with screaming trumpet and honking saxophones. Or perhaps the image was of a rhythm-and-blues band gone berserk.

The second piece, though sprawling and too long, was nevertheless filled with exciting passages. A slow tenor solo was followed by a bass interlude and then a call to arms by the horns, a militaristic theme-statement, a fast tenor solo, ensemble interlude, solos by all the horns at very rapid tempo, a return to the theme, another call to arms, and a bansheelike concluding ensemble.

To this listener, there seems to be a great deal of wild humor in Ayler’s music. Though often vehement, it is celebration rather than protest; much of it has the sheer “bad boy” joy of making sounds.

Whatever one’s reaction to this music, there can be little doubt that it contained the spirit of jazz. Some may dismiss it as untutored, primitive, or merely grotesque, but it certainly has the courage of its convictions and is anything but boring or pretentious.

—Dan Morgenstern

*

Astor Place Playhouse, New York, February 1966

The East Village Other (Vol.1, No. 8, March 15-April 1, 1966 - p.5)

THE NEW JAZZ by Rupert Kettle

John Cage recently had a 3 p.m. appointment with Village Voice jazz critic, Micheal Zwerin. According to Mr. Zwerin, he arrived at exactly 3.

“You’re right on time,” said Mr. Zwerin.

“It’s music,” said Mr. Cage.

Apparently most of the members of Albert Ayler’s group, who appeared at the Astor Place Playhouse on Monday evening, February 7th, feel such a musical discipline to be expendable, and most of them didn’t show up until at least an hour past starting time. Musical discipline aside, one is prompted to direct a couple of questions toward Messrs. Levin, Hentoff, et al: Do a lot of people miss out on gigs because of the extremely ‘avant’ profundity of their work? Or because of some abstract, racially discriminatory undercurrent? Or simply because of an inability to punctually keep commitments?

The program, however, was well worth waiting for in most respects. Ayler, to me, is the most important member of the contemporary jazz community, both as an individual player and as a leader. In the recent concert his mastery of his instrument was obvious, and his solos were intensely beautiful; his group, which sounded best when playing ‘tutti,’ often had as many things going as there were men on the stage (one could only have wished that its members had been seated in various places around the small theater, rather than all lumped together up front).

Trumpeter Don Ayler and alto saxophonist Charles Tyler were extremely inventive in full ensemble passages but did not come near measuring up to their leader’s soloist ability.

Cellist Joel Freedman, an astounding musician, often couldn’t be heard over the rest of the group. It is hoped that in the future some adjustments can be made to allow his presence to be realized; perhaps electronic amplification; perhaps a seat closer to the front of the stage; I don’t know. But something should be done to insure that his brilliant playing will be audible.

Drummer Charles Moffat - whoops, “Percussionist” Charles Moffat (complete with a set of orchestra bells to prove it) - was, unfortunately, fodder for those who would shoot George Russell’s by now infamous cannon (“The avant garde is the last refuge of the untalented.”). An incredibly poor drummer who is best off hiding behind the “percussionist” moniker, Mr. Moffat evidenced an ability to keep time that was on an even par with his ability to keep appointments. His constantly choppy and very obvious use of two-measure, 4/4 phrases, during passages in which a steady pulse was maintained, made his work seem out of place with that of his cohorts.

However, the concert was enjoyable as a whole, and Albert Ayler’s work is always to be commended. He has said someplace that it’s no longer a matter of scales or chords or even notes, which would seem to indicate that he may be getting very close to something. He has gone on to say, however, that it’s now just a matter of feelings. When Ayler can eliminate that idea and get down to that of which it’s really more a matter than anything else - sound - he’ll really be something. Of course, it will then be said that he’s no longer playing jazz, but Ayler has further said that he has no use for that appellation anyway. Yeah, he just may get into something...

Postscript - Mr. Nat Hentoff was not in attendance.

*

Coda (April / May 1966 - p.25)

. . .

Albert Ayler’s group played four concerts of tremendously exciting music. Ayler’s sound is at its best with his brother Don on trumpet and with Charles Tyler on alto. I have as yet to hear anything more exciting than the sound of these three horns soloing simultaneously. Once one really learns to listen, patterns become apparent and their intricacy in sound and emotion is nothing less than astounding. Charles Moffett, in New York for some weeks in between jobs with Ornette Coleman in Europe, played his heavily rhythmical drums while Joel Freedman’s haunting cello was there instead of a bass. Ronald Jackson, a Moffett pupil, took over the drummer’s chair for the last two concerts and proved himself to be an energetically vibrating addition.

Ayler’s music is becoming rapidly popular in New York. He is a master in bringing about that intensity, that forceful feeling of joy for life that literally stirs his audience to its feet. A very dexterous hornplayer, not in any way slowed up because of technical shortcomings, Ayler extracts from his horn a most wildly varied series of sounds. Playing freely at a height where most tenor players can hardly reach, then again diving deep down into the more husky ranges of his instrument, Ayler is in control of his musical outpourings all the way. When first encountering this free-flowing force one might be slightly taken aback, but it can’t be long until one must be completely engrossed in the happy complexity of Ayler’s extraordinary music.

Ayler took this opportunity to try out quite a number of new tunes of which especially the majestic and moving “Our Prayer” written by brother Don is a new powerhouse which gives Albert the opportunity to immediately plunge into a solo - Don and Tyler playing the melody - so strong and charged with emotions that he had even his staunchest fans gasping for breath.

. . .

- Elizabeth van der Mei

*

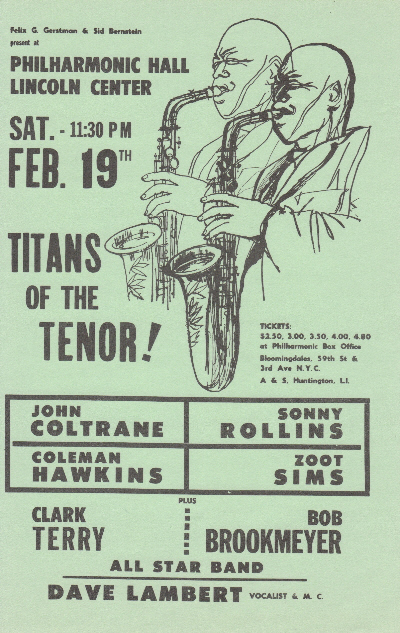

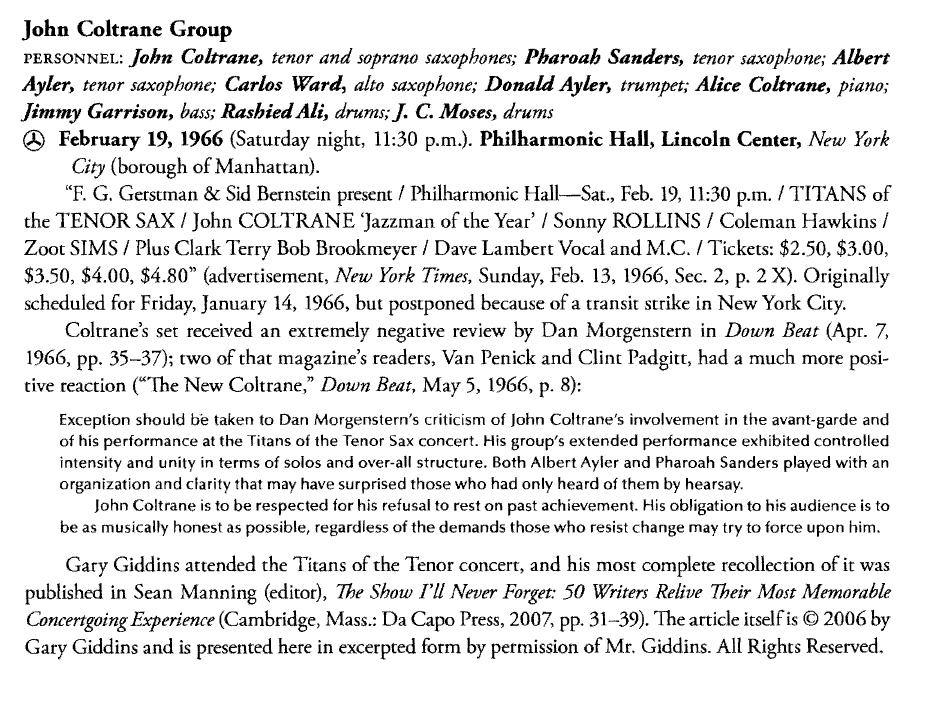

‘Titans of the Tenor!’ Philharmonic Hall, Lincoln Center, 19 February 1966

|

|

|

From Three Notes with Albert Ayler: Impressions of the New York Scene by John Norris - Coda (April./May 1966, pp. 9-11)

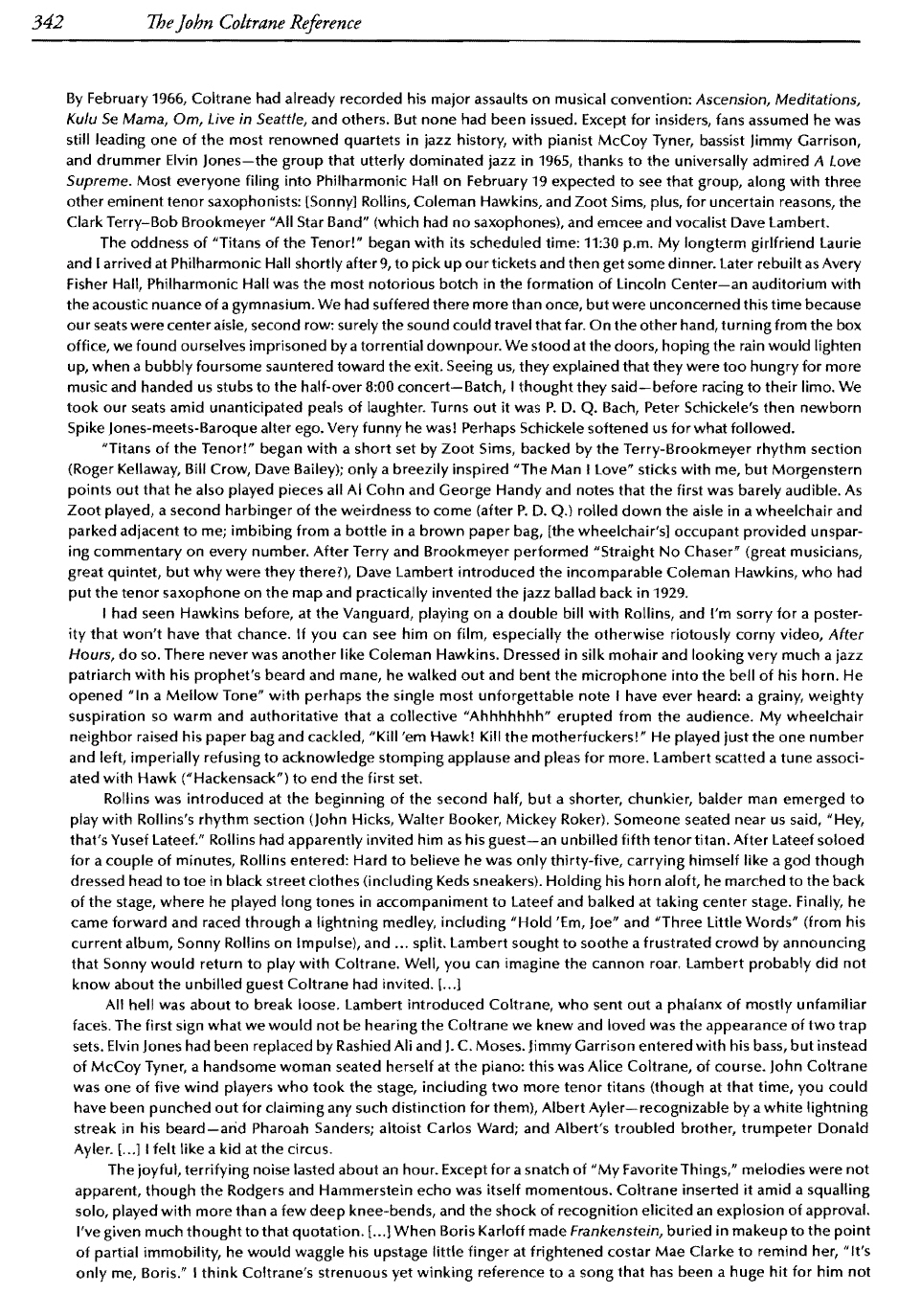

The “Titans Of The Tenor” concert at the Lincoln Center’s Philharmonic Hall on February 19 demonstrated very clearly the wide gap between what is happening musically and what the jazz audience is prepared to accept. The culmination of this concert was the 40 minute set by John Coltrane’s band - that included Don and Albert Ayler and Pharoah Saunders. The music played was unbelievable. The intensity emitted from the other musicians’ horns made Coltrane’s offerings sound sedate in comparison. The music began with a long, Spanish tinged bass solo from Jimmy Garrison before the music exploded with Coltrane’s familiar “My Favorite Things”. And yet what he played was not exactly the same. He has added a new dimension to his soprano work. It is fuller, more highly vocalised and the impact of his music was helped by the backing, which exploded all around him. Rashied Ali, his new drummer, has to be seen to be believed. His left hand provides an incessant flurry of accents delivered so fast his hands are a blur and the continuous explosive barrage of percussion was unrelenting. J. C. Moses, in comparison, was able to contribute but little and yet he blended well with Rashied’s more complex playing. In addition to this battery of sound, further rhythmic excitement was projected by the other hornmen using tambourines, shakers, maracas etc. It was an insistent and propelling rhythm that sustained itself throughout the solos of all the musicians. Pharoah Saunders’ tenor work was astonishing. His whole solo was in such a high register it sounded like a violin. Following on from Coltrane’s soprano statement it was fascinating to hear.

With Saunders and Albert Ayler, the new music has two musicians of diverse but powerful voices. Ayler’s intensely vocal music was beautiful to hear - his tone is virile but sad, and he often moves into voluminous mutterings before returning to relative calm. His brother, Don, is a trumpeter the like of which is rarely heard. His solo work is a violent cleansing of his soul. He practically fights over the instrument as a continuous stream of notes pour forth. Despite the speed of his playing, he manages to emit notes rather than noise. Effective once, as was heard at this concert, his solo work does seem limited, however. He sounded better when he returned with his brother for a remarkable duet.

Their music is hard to describe - in much the same way that it is hard to listen to at first. The thematic material is often naively simple but Albert Ayler plays with facility beyond the legitimate range of the instrument and what he produces are not just freak effects.

Carlos Ward is Coltrane’s new alto saxophonist - a musician who may well make his mark on jazz. He suffered a little in comparison with the other musicians but soloed effectively.

This piece of music by Coltrane’s augmented band, was all solo music. There was no attempt made to produce any real group music. Probably there wasn’t time, for the Ayler’s were only invited to appear a couple of days before the concert. Apparently Coltrane had been trying to persuade the promoters to book Ayler’s own group, but when this failed he solved the situation by inviting them to play with him. It was a fitting climax to a concert that had proved noteworthy in many respects.

Zoot Sims had opened the proceedings with a rhythm section of Roger Kellaway (pno), Bill Crow (bs) and Dave Bailey (dms). Sims seemed slightly below par on this occasion and his sound failed to project into the vastness of this auditorium too clearly. It was pianist Kellaway who took the honours with his solo on The Man I Love.

After three tunes Sims was replaced by Clark Terry and Bob Brookmeyer, who delivered a succinct version of “Straight No Chaser”, in the course of which both hornmen trotted out their favorite licks in their best manner.

It was the first appearance of Coleman Hawkins that produced the first really worthy music of the evening. Stately in appearance, with long grey beard in the manner of an ancient prophet, Coleman Hawkins blew one exclamatory note of In A Mellotone and demolished all that had preceded him. He then dug in and built a long authoritative solo that was noteworthy for its deliberate and forceful direction. Very few of the characteristic Hawkins arpeggios were present and he really produced some beautiful music. This was a jazz master clearly demonstrating that he had no intention of giving way to anyone.

Following intermission, Sonny Rollins came on stage with Yusef Lateef as an additional guest. Lateef opened up with a good solo and then Rollins took over. He proceeded to play a variety of tunes for some fifteen minutes while he walked around the stage, used the wall to alter the tone of his notes, ducked and avoided the spotlight, played behind the accompanying musicians and only occasionally utilised the microphone. It was a good performance and obviously Rollins feels that the visual aspects of his presentation are an asset to his presentation. The music he played seemed somewhat static however. He never once built up to anything that remained in one’s mind. What he played could be summed up as a brief sample of a shuffled together Sonny Rollins Songbook. John Hicks (pno), Walter Booker (bs) and Mickey Roker (dms) were the supporting musicians and they never emerged into the spotlight with the exception of Walter Booker.

It was Coltrane’s music that captured the heart and mind. It left the audience in a state of shock. Few seemed prepared for the barrage of music that soared over them and they remained seated, unable to applaud, even after the musicians had left the stage and the lights had come up.

Albert Ayler’s music produced the most startling and satisfying music of the visit and what he has accomplished is comparable to Ornette Coleman’s breakthrough in the late 1950’s. This man’s music is so completely individual, and yet so strong, it can completely engulf the listener. It can also offend mightily because a casual listen might give the impression of absolute nonsense. Ayler has been playing Monday night concerts at the Astor Playhouse, a small intimate theatre in the Village, not far from the Five Spot. The concerts are presented by ESP-Disk, a record company that has helped considerably in the documentation of the new music.

Ayler’s music is, essentially, group music. The combination of his tenor sax, his brother’s trumpet and altoist Charles Tyler produced a sonorous sound combination of great richness. It is strange that musicians who have such fantastic command of their instruments produce music of extreme simplicity. The themes that Ayler uses are nearly all drawn from the “folk” repertoire of children’s songs, familiar in part to nearly everyone. It is what they do with them that is so astonishing. The music that they play is sometimes startlingly like New Orleans jazz. There is more than a trace of parade style music and the interaction of the three horns produces music similar in approach. An even more startling comparison of this can be heard in Ayler’s recording of Witches and Devils (Danish Debut - English Transatlantic TRA130).

*

From The John Coltrane Reference by Lewis Porter, Chris DeVito, Yasuhiro Fujioka, Wolf Schmaler and David Wild (Routledge, 2008).

|

|

|

Village Vanguard, New York, May 1966

Down Beat (Vol. 33, No. 14, 14 July, 1966, p. 30-31)

Albert Ayler

Village Vanguard, New York City

Personnel: Don Ayler, trumpet; Albert Ayler, tenor saxophone; Michel Sampson, violin; Lewis Worrell, bass; Ronald Jackson, drums.

For one Sunday in May the Village Vanguard was engulfed by the Ayler sound. Again Albert Ayler managed to have his music sound different from the last time I heard him, which was only recently.

The addition of a young Dutch violin player, Sampson, gave a different dimension to the music. Sampson joined Ayler when in Cleveland, Ohio, recently, where the violinist was a soloist with the Cleveland Symphony Orchestra.

The group started with Ghosts, one of those hauntingly simple compositions, designed, however, to show all the leader’s virtuosity. A dexterous player, in no way slowed by technical shortcoming, Ayler extracted from his tenor saxophone a wildly varied series of sounds, making “ghosts” travel through an abundance of emotions, playing freely at a height most tenor players can hardly reach and then diving deep into the huskiest ranges of his instrument, coming back to the theme, from which a sparkling trumpet solo grew into a crashing wildfire of sound. Tenor then joined trumpet, surging into a splashing waterfall of music.

Once one learns to listen, patterns become apparent, and their intricacy can be astounding.

Technically brilliant, Sampson was remarkable in showing how two different worlds of music blended into a new sound so exciting and with such a forceful feeling of joy for life that it literally stirred a cheering audience to its feet.

Spirits Rejoice and Bells were marchlike tunes with a lot of collective improvisation, quick-moving and kept interesting by keeping the solos on the brief side, bringing a curious resemblance to the marches of the grand days of New Orleans jazz.

Albert Ayler took the opportunity to try out quite a number of new tunes.

There was a tune, untitled as yet, with changing tempos, that builds into a near symphonic pattern; there was what could have been an East European folk song, full of nostalgia, during which sometimes the sound of the tenor and of the violin could hardly be distinguished, together creating a delicate musical weave of exquisite beauty; and Our Prayer, written by Don Ayler, a majestic tune and a real powerhouse, permitting Albert to plunge into a devastatingly forceful solo, with the rest of the group repeating the melody line.

Worrell’s inventive bass playing added greatly to the excitement, and Jackson, although with Ayler only a few months, created an illusion of rhythm rather than a beat. He and Worrell gave that particular brand of strong vibrations indispensable behind the strong Ayler horns.

Albert’s sound has changed again. Some of the harsher aspects of his music have been abandoned, leaving more room for lyrical moments and getting closer to a direct translation of emotion into sound.

When first encountering this free-flowing force, one might be slightly taken aback, but in the end one walks away overwhelmed by the force, joy, and excitement of the Ayler sound.

—Elisabeth van der Mei

Next: The 1966 European Tour

|

|