|

Music Is The Healing Force Of The Universe The Inconsistency of |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

News from 2016 - April to June

April 1 2016

Ted Joans I have to thank Jochen Behring and Pierre Crépon for sending the following article from Coda (August 1971, pp. 2-4): ‘Spiritual Unity—Albert Ayler—Mister AA of Grade Double A Sounds - by Ted Joans. |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Michel Samson Michel Samson (who played violin with the Ayler band from April 1966 to July 1967) receives short shrift from Ted Joans above (as does Bill Folwell - funny that) but gave his side of the story in an article, ‘Avonturen in de New Thing’ in the Dutch magazine, Jazz Bulletin in June 2012. The original article (with photos) is available here, but I have to thank Kees Hazevoet for taking the time and trouble to translate it into English. The section on his time with Albert Ayler is particularly interesting.

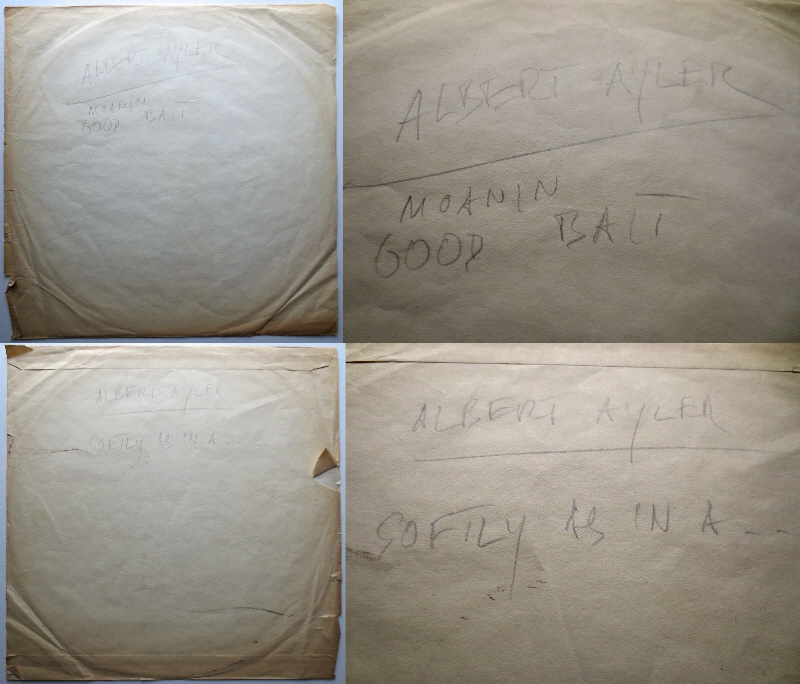

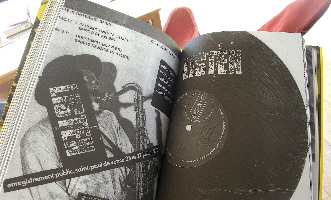

Adventures in the New Thing By Rudie Kagie In 1965 he played with Ornette Coleman and from April 1966 with Albert Ayler for a year and a half. But the Dutch violinist became interested in other things and said goodbye to Ayler and his music. To capture his memories, Rudie Kagie visited him in his present hometown of Louisville, Kentucky. ‘The violin’, says Michel Samson (1945). ‘Everything I know about politics, history, art – about everything, I know because of the violin. From age five onwards that instrument has completely dominated my life.’ On American record sleeves of Impulse and ESP his surname is consistently spelled wrong. Sampson really has to be without p (although correction would by now only create confusion, because the error has been repeated on almost all cd reissues). The invitation from Samson to come and look him up in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky, dates back from a previous meeting in Amsterdam twelve years ago. It took a while to materialize. Diehard fans of the New Thing of the 1960s will perhaps remember Michel Samson as the white, clean cut, always dressed in black suit, Dutch young man who – outwardly unmoved – accompanied the free tenor improvisations of Albert Ayler (1936-1970) on violin. As a pioneer, Samson deserves more than just the footnote in the history of the avant-garde that he has been allotted – just take the reproach in [Dutch newspaper] Het Vrije Volk, which, after the concert in the Doelen, Rotterdam, accused him of ‘lust-murdering the violin’ – even though he considers the year-and-a-half during which he handled the bow at Albert Ayler’s side as a musical aside. He has done more important things in his life, he says. He talks passionately about his painting, in which he now invests a lot of time. In the car, during the drive from the airport to his home on the Fairhill Drive in Louisville, it already becomes clear that past fame barely occupies him. Gee, is Donald Ayler, the mentally unstable younger brother who played trumpet in Albert Ayler’s band, already dead for five years? The obituary had escaped Samson’s notice. What he does remember: ‘Let’s practice soundwise’, the strange Donald used to say. Nerves of steel It took half a life before Michel Samson understood why his father insisted that his son had to become a concert violinist. The violin was the instrument that would change everything for the better. His father – painter and draftsman of portraits for court records in [Dutch newspaper] De Telegraaf – was Jewish, his mother catholic. ‘That I had to take violin lessons was a post-war revanche, an attempt by my father to salvage the honour of family members that had been deported’, reconstructs Michel Samson. ‘No instrument more Jewish than the violin. Almost literally a weapon. Comparable with bow and arrow. When you hold a violin for the first time, you feel the great tension of the strings. To play the violin well, you got to have nerves of steel. An uncontrolled movement can be heard around widely. The violin is a time bomb.’ Ever since his childhood, Samson says, he has been driven by ‘a great appetite for all kinds of music’. He didn’t want anything but to please his father, his father who thought practising to be more important than regular teaching. He withdrew his three children from school in order to teach them himself – until the school inspector rang the bell and return to the classroom was inevitable. Love for jazz was fed by jazz records from the collection of the American embassy. Besides, young Michel Samson had noted that, during the 1950s, the winners of important classical competitions for violin and piano always originated from either America or Russia. If he really wanted to accomplish something in music, he had to travel the world, away from The Hague. Perplexed In those years, musical masters of world fame weren’t as unapproachable as today. In 1961, Michel Samson (who was 16 at the time) called up his big example, Yehudi Menuhin, at the Amstel Hotel in Amsterdam. ‘Come along tomorrow morning when I’m rehearsing Brahms with the Concertgebouw Orchestra’, the maestro told him. The invitation resulted in an unforgettable experience. Samson: ‘I waited for Menuhin at the artists’ entrance of the Concertgebouw, went upstairs with him and had to wait until the rehearsal was over. When he came back, he made me play Bach’s Chaconne in front of the people who were with him. After that he made everybody leave the room and told me what I was doing wrong in his view. That was on a Wednesday. The next Saturday he was going to perform at the Kurhaus in Scheveningen [near The Hague]. If I’d pass by before the concert, we could talk some more and I could demonstrate the progress I had made. While we were sitting together in a room, all of a sudden the door flew open. Menuhin’s impresario looked at me furiously and yelled: “Out you! This man here is like a child, he doesn’t realize that he has to play Brahms in a few moments!”. The great Menuhin was perplexed, with a face asking ‘what’s going on here?’. Sometimes there was a strange inconsistency in his playing. If he hadn’t prepared himself well enough, he had difficulty handling his bow. Shortly after, Michel Samson went to Baden-Baden with the Lorelei Expresse to take part in a summer course for young violinists, where he received tutorage from his Polish-Mexican role model Henryk Szeryng. One year later he obtained a Dutch scholarship and went to Rome to study at the Academia di Musica da Camera to study with the Argentinian violinist Alberto Lysy and, through him, with many other great names. ‘In Rome I met with the Living Theatre, who were performing their play Mysteries and Smaller Pieces. Towards the end, Piet Kuiters strolled on stage with a saxophone and improvised until the audience left when they understood the play was over. Kuiters wasn’t really a saxophonist, but a pianist. I loved that free jazz. If you enjoyed hanging around there, you automatically became a member of the Living Theatre. What Piet Kuiters had been doing on saxophone, I was doing with the violin – I filled up the part at the end of the performance. ‘In Trieste an interesting incident happened during an episode called The Plague. The actors spread through the hall and acted as if dropping dead. They were carried away on stretchers and piled on top of each other. That growing pile of people offered such a horrifying sight that someone called the police: this couldn’t be, this shouldn’t be. The police indeed arrived, but when the actors were summoned to get on their feet, they just kept lying. The officers started to beat and club them. Typically 1960s’. A boy’s dream While being away from Rome for a short holiday, Samson seized the opportunity to attend the first concert by Ornette Coleman in the Netherlands during the nightly hours of October 29, 1965 at the Amsterdam Concertgebouw. Just like he previously had approached Menuhin, he now contacted Coleman. And successfully so, witness the (anonymous) review in the [Dutch newspaper] Algemeen Handelsblad: ‘The atmosphere of the finale was one of a happening. Ornette Coleman grabbed his violin, another violinist joined the trio, together with bassist Izenzon they executed a serious remodelling as well as a fascinating background for Dutch trumpeter Nedly Elstak, who joined the group at Coleman’s request’. A boy’s dream came true, Samson says while looking back at this historical concert. In a phone call to impresario Lou van Rees’ office that afternoon, he learned that Coleman was staying at the Krasnapolsky Hotel. He admired the musician that improvised on a plastic saxophone, but was even more intrigued by rumours that the great Coleman had also taken up the violin. ‘I thought it would be fantastic to play free jazz with him on the violin. During the late afternoon I went to the Krasnapolsky Hotel. At the bar I wrote a note for him, explaining that I was a violinist and would like to meet him. Ornette was sitting in the restaurant, read the note that the waiter gave him and waved to me to come over. Later, in his room, he asked “Would you like to play something?”. I played some Bach, solo, which he liked a lot. Then he asked me the most important question someone ever asked me: “Can you play something that is in your head?”. I had never thought about that before. ‘He invited me to come to the concert that night. There would be an entrance ticket for me at the counter. I had a balcony seat. After the first set Coleman took the microphone and asked : “Michel are you there? Why don’t you come down, man, and play with us?”. While the audience applauded I came down the stairs of the Concertgebouw to play with him. An amazing experience. Of course Coleman wasn’t a great violinist. He just scratched away, but I thought it was great that he did it. Much later I found out that it had already been done long before. The way the composer Count Gesualdo da Venosa applied Greek musical theory to his madrigals was more way out than Ornette Coleman – and that was during the Renaissance!’. Warm and sweet ‘I wanted to go to America, because that’s where it was happening. At the time, the most important training institute was the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. All violinists winning at international competitions were from Curtis, not from Juilliard. If you were admitted to Curtis, training, food and shelter was paid for. Late in 1965, I went to New York by ship of the Holland-America Line. I paid for the trip by playing four times aboard the Nieuw Amsterdam. Twice first class and twice second class. ‘I arrived in New York, December 18. Right away, I could stay with the theatre critic Michael Smith of the Village Voice. The Living Theatre had given me a list of people I could contact once I was in New York. It was like one large family. At the time, everybody was very warm and sweet. The fact that I looked good may have helped, as many of these contacts were gay’. (Michael Smith published parts of his diary, full of sex and drugs, from the hectic 1960s on the internet. On December 19, 1965 he noted: “Two young Dutchmen, Oliver Boelen and Michel Samson, friends of Rufus’s, were in the living room when I woke up. [....] I invited them all to come to Judson for the matinee. [....] Joyce held up her cup to ask if a wanted more wine. I said not. She is talking to Gordon. The Dutch boys want to stay at Joe’s but he doesn’t want them to. Gordon drove Joe, Lee and me to the Village in his Porsche. He went home and they came up. Charles took Oliver and Michel to his house to sleep.”) Michel Samson continues: ‘Max Tak – a violin freak, who could fix things for Dutch artists – worked at the Dutch consulate in New York. Through him I could audition with Ivan Galamain, a big name who had produced well-nigh all big stars of the second half of the 20th century. Galamain also taught at Curtis and arranged for me to be admitted there. Meanwhile and thanks to Max Tak, I regularly had gigs. ‘The writer, Peter Bergman, who I had met through the Living Theatre in New York, called me at the Windermere at 92nd Street where I was living. His father was about to open a men’s fashion shop in Cleveland, Ohio. Peter thought it to be a good idea for me to play some at the opening. I could use the money and at the same time I could choose a new wardrobe at that shop. ‘That’s why I was in Cleveland on Saturday April 16, 1966 where, as I had read in the newspaper, Albert Ayler’s quartet would perform at the La Cave jazz club. During the afternoon I went there and found Albert rehearsing with local musicians and, of course, his brother Donald on trumpet. I introduced myself and said that I had played with Ornette Coleman in Amsterdam. “Do you have your violin with you?”, Albert asked. From that moment on we hit it right away. That night I played in his band and the following night again, at the same club. Obviously, I was wearing my new suit that I had been allowed to choose at the fashion shop the other day’. ‘After the concert Albert said: “We’ll play at Slugs in New York on May 1st, will you be there with us?”. Of course I was! I haven’t kept a count, but I think we performed together some 30 to 50 times in total’. (In the liner notes of the Impulse album Albert Ayler in Greenwich Village, Nat Hentoff quoted Albert Ayler: “From the beginning, we hit it off musically. Michel, too, is a man who spent a long time searching for peace’.) An endless number of joints An exciting time, you may perhaps think. But according to Samson it wasn’t that exciting at all. Of the legendary jazz club Slugs, he mainly remembers the ‘pretzels and peanut shells on the floor’. For the rest, time mainly passed with smoking an endless number of joints. Before morning rehearsals at the aunt’s home in Harlem (where Albert and Don usually spent the night dozing in a chair), Samson was picked up at the nearby subway station, as it was too dangerous for him to walk in the neighbourhood with a violin case all alone. The rest of the day they strolled the streets of Manhattan, ‘hoping that a crumb would fall their way’. ‘We brainstormed endlessly about commercial success. Albert didn’t intend to cause confusion. He wanted to make it and be part of the establishment. This came with a certain degree of opportunism. I think that me being part of the band was because having a white violinist from Europe made it easier to gain a foothold with record companies and jazz clubs. Becoming famous was part of the 1960’s. The Beatles and The Rolling Stones were the great examples. ‘Albert wanted to tour in Japan and was considering to incorporate Japan-like themes that the Japanese would like. At the time, Art Blakey and all those boppers were beginning to make real money in Japan, not in Europe. Albert relentlessly tried to get access to the mighty producer and impresario John Hammond, the man who could arrange a contract with CBS. At long last we got an interview, but Hammond thought nothing of what Albert was doing. Instead, Hammond gave me a contract. ‘I think it had to do with him being the brother-in-law of Benny Goodman, who had been a good friend of Béla Bartók and the famous Hungarian violinist Joseph Szigeti, a Bach specialist. Somehow it clicked between us. John Hammond has helped me a lot getting studio gigs. As long as it earned me money, I didn’t mind. ‘Through Hammond I came in touch with John Handy, an alto saxophonist who was selling quite well at that time. Miles Davis came over to listen when we played at The Dome. After the concert, Miles came to me and almost wanted to punch me in the mouth. He thought I was disloyal to Albert. “Why are you playing that boogaloo fuckin’ music man?”. Miles thought John Handy was a complete zero. The opportunist side ‘A removal began to arise between Albert and me. I shouldn’t be allowed to play with John Handy. He was jealous. As for myself, I got increasingly fed up with the pseudo-religious and would-be philosophical bullshit that Albert came up with. The rhythm section was constantly changing. The dialogue would go: “Well, man, Sunny [Murray].... he doesn’t have that energy, man...”. One month later it was: “Well, Beaver [Harris], he is a funny cat, but he doesn’t have that energy”. The musical judgment had nothing to do with knowledge or rationality. Or it was expected that the sidemen would take a very humble stance. ‘I didn’t suffer from that. I didn’t need to be humble, I could as well have come from another planet. It was just approaching the end, at all fronts. Albert Ayler’s music woke up something in me that didn’t need to be woken up anymore. I thought it was leading nowhere’. That Samson always felt like an outsider in Ayler’s bands, also shows between the lines in the only interview with Samson from that time which has been preserved. (Even the very detailed archive of newspaper clippings of the Public Library in New York doesn’t have any references). After a concert with Ayler at the Berliner Jazztage 1966, Bert Vuijsje interviewed the violinist for an hour for [Dutch magazine] Jazzwereld (No. 11, March 1967). Significantly, the headline read: “I don’t really try to play jazz”. The interviewee spoke passionately about the great classical composers, but he hardly mentioned jazz at all. It was clear how he felt about the direction his future should take. Michel Samson now: ‘The last time I played with Albert was at the Newport Jazz Festival 1967. When, in 1968, that R&B album New Grass came out, I already couldn’t care less. After John Handy, I quitted jazz completely. This also had to do with a growing aversion against the opportunistic side of myself. I had other interests. I wanted to paint, perhaps a career as conductor’. ‘I indeed began doing these things. I was assistant-conductor with several American orchestras and also conducted Dutch orchestras. I never became an American citizen. From 1981 to 1985, I lived in the Netherlands, where I was deputy leader of the violas with the Omroeporkest (Radio Orchestra). However, the woman with whom I was married at the time and the children couldn’t settle in the Netherlands and we went back to the USA. For 15 years, I taught at the University of Louisville. In 1997, I became a violin dealer, that is to say: European representative and partner of Bein & Fushi in Chicago. I always did the visual arts as a side line. Every now and then the past knocks at his door: is he perhaps the Michel Sampson who played violin with Albert Ayler in the 1960s? Sometimes he gives an interview for a documentary or a book about that period. Many times he has been asked to revive the musical revolution of Albert Ayler on stage at a festival or in a recording studio. ‘I never responded to those requests’, he says. ‘It is gone. It is meaningless to try and repeat something that is so much connected with a certain time period’. [Originally published in Jazz Bulletin No. 83, June 2012 * Birdnotes BNLP2 First, I have to thank Jochen Behring for letting me know about this. Bird Notes 2 - otherwise known as The First Recordings Volume 2 - received its first release on a Japanese label. But prior to that there were the test pressings, which existed in two forms, one with three tracks the other with four. Only a handful of these were made and two (one of each version) recently turned up on ebay. The asking price for each was $6000. The auctions have now ended, but the ebay pages may still be available for a while: 3 track version, 4 track version. I’ve added the photos and descriptions to the Something Different!!!!! covers page and here’s the picture of the inner sleeve of the 4 track version: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

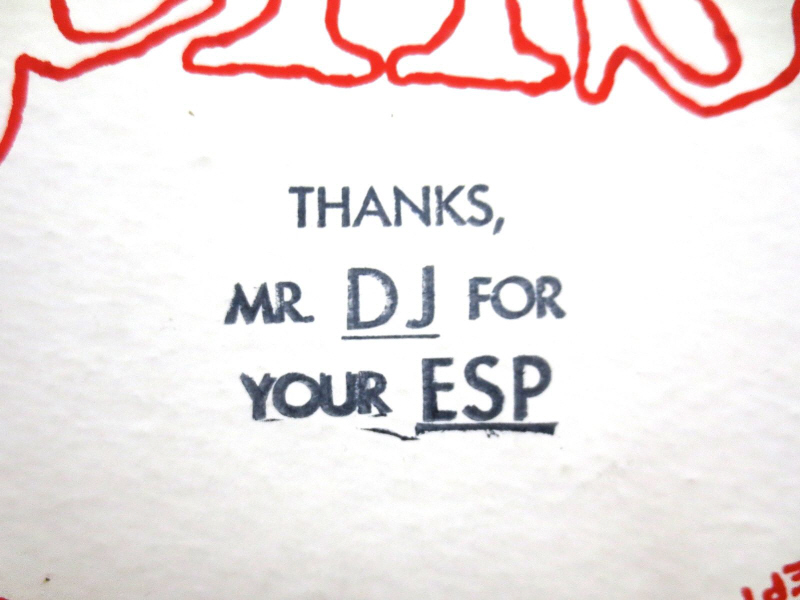

The ebay merchant also had another interesting item in his collection, an original promo copy of Bells (only $650). Again, the details may still be on ebay, but I’ve added the photos and description to the Bells covers page. The front cover (it’s blank on the back) bears this stamp: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

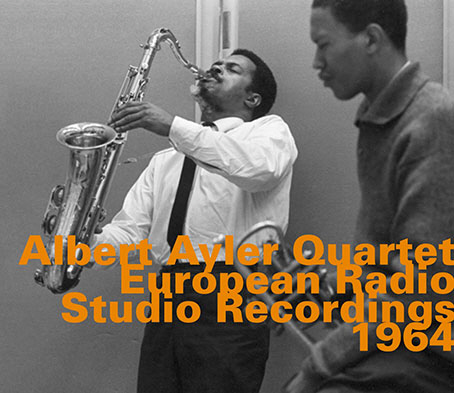

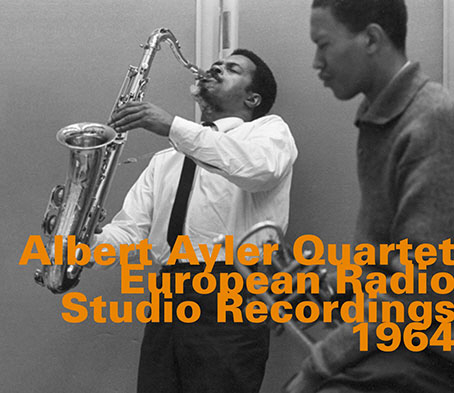

‘New’ releases This may be a bit premature since I don’t have the full details but Pierre Crépon let me know that HatHut are preparing two more Ayler products. The first is announced on their Upcoming Releases page as hatOLOGY 678: ‘Albert Ayler Quartet with Don Cherry - European Radio Station Recordings 1964’, but there are no further details so we’ll have to wait awhile to find out whether this is ‘new’ material, or a rerelease of the recordings previously issued on The Copenhagen Tapes and The Hilversum Session. Meanwhile Pierre did come across this picture on the merzbo-derek site which seems to be the upcoming CD’s cover: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

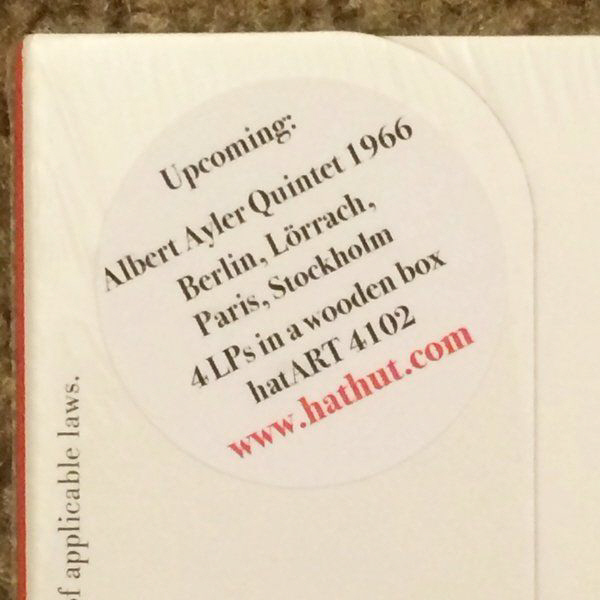

And David Mittleman came across this sticker attached to the recent rerelease on vinyl of Sun Ra’s double LP set, Sunrise In Different Dimensions (hatART 2101). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

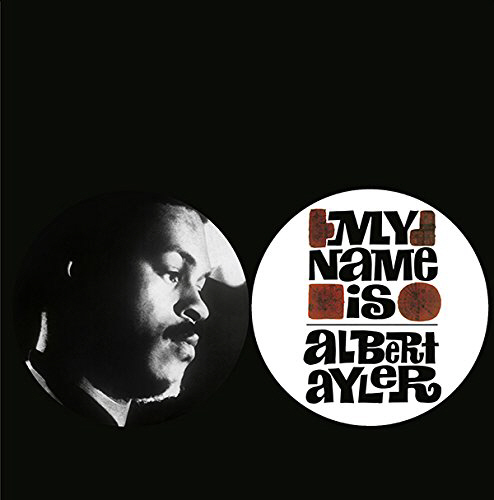

On the subject of reissues, My Name Is Albert Ayler has just been released on vinyl (rather than the mp3 versions with their jolly titles we’ve grown to know and love). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

According to CDUniverse and amazon it’s on the Goodfellas label (a name designed to instil confidence), however, Goodfellas seem to be a distributor and on their site it’s listed as being on the Jeanne Dielman label, which is confirmed by Forced Exposure. Jeanne Dielman also seems to have released The First Recordings Volume 1 on vinyl, and this seems to be its rather minimalist cover: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

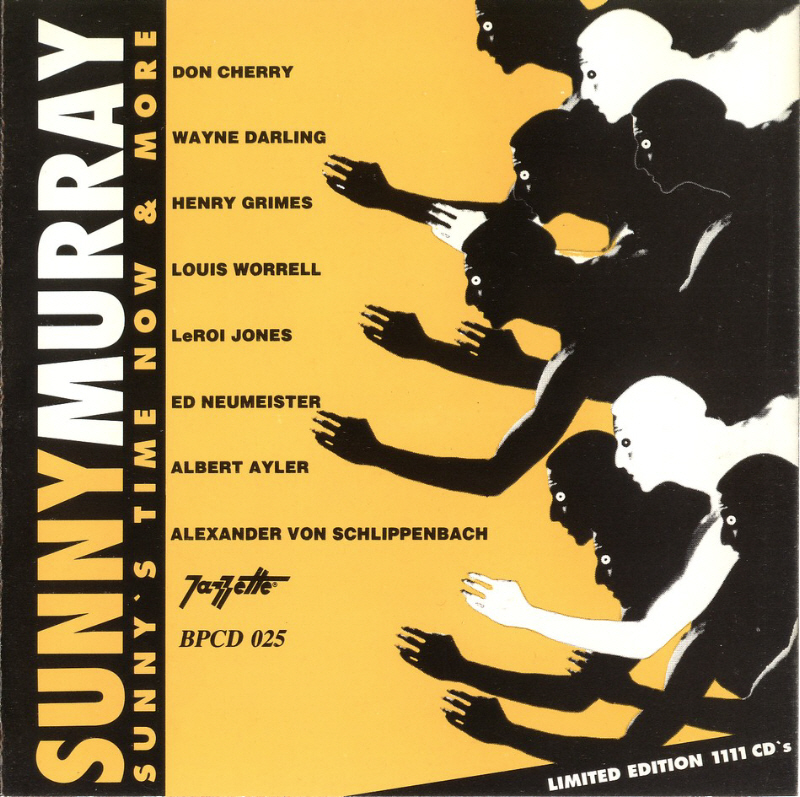

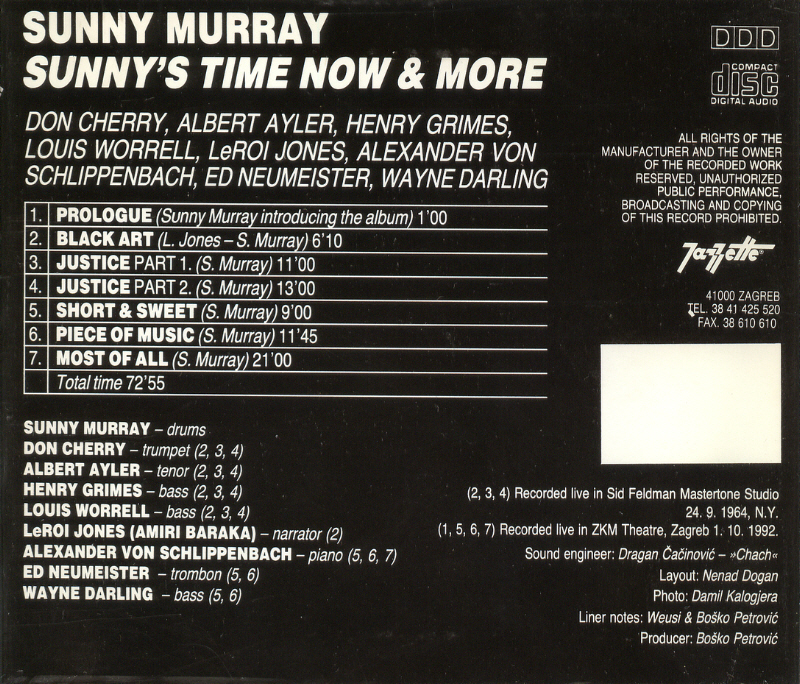

And you’d think that would bring us back to the beginning and we could leave discographical matters for this month. But no. I started this site to sort out the Ayler discography but it doesn’t seem to get any easier. * Sonny’s Time Now ... again I started this site to sort out the Ayler discography but it doesn’t seem to get any easier. Pierre, with the help of Ernst Nebhuth and Igor Popović, came up with this weird addition to the Ayler discography. It’s a Sunny Murray compilation, emanating from Croatia, and containing the original three tracks from Sonny’s Time Now alongside later live recordings made in Zagreb in 1992. More information on the Sonny’s Time Now covers page but here are the front and back covers: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

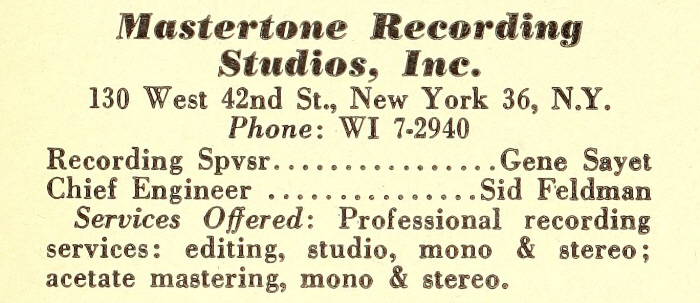

Tracks 2 - 4 are the three tracks from the original version of Sonny’s Time Now, but in a different order and with different titles. On the Jihad LP there were 3 tracks: ‘Virtue’, ‘Justice’ and ‘Black Art’. ‘Justice’ was split in two, so ‘Justice Part 1’ appeared on the first side and continued as ‘Justice Part 2’ on the second. A subsequent Japanese LP version included a fourth track, ‘The Lie’ as a 45” single, and the Japanese CD version (DIW-355) included all four tracks. On this Croatian CD, ‘Black Art’ comes first, then ‘Justice Part 1’ (which is ‘Virtue’) and ‘Justice Part 2’ (which is the complete ‘Justice’). The remaining three tracks (and the Prologue) were recorded in Zagreb in 1992. The other interesting thing about the back cover is the recording information given for Sonny’s Time Now. According to this it was recorded at the Sid Feldman Mastertone Studio, New York, on 24th September, 1964. On the face of it this is obviously wrong since the Ayler/Cherry Quartet were in Europe at the time. However, the date and place of the session has never been pinned down - it’s usually just given as November, 1965 in an unknown studio. Of course, once you start down the rabbit hole and consider that just the year is wrong, then you discover that 24th September 1965 was the day after the Judson Hall recording of Spirits Rejoice, and then you start to wonder why Don Ayler wasn’t invited to the session rather than Don Cherry, who hadn’t been a member of Ayler’s group since December 1964. At which point you think maybe, for sanity’s sake, we leave the recording information on this Croatian version of Sonny’s Time Now as a mistake. But, just in case, here’s the listing for the Mastertone Studio from The Radio Annual and Television Year Book of 1964. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Books You know where you are with books. Again, this comes courtesy of Pierre who let me know that there are several books by Philippe Robert which touch on Albert Ayler and are not mentioned in the Bibliography. I’ve remedied that now but I thought I’d mention them here too. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Musiques expérimentales: Une anthologie transversale d'enregistrements emblématiques |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Great Black Music: Un parcours en 110 albums essentiels by Philippe Robert. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

And two books featuring material by Philippe Robert on Albert Ayler and the Fondation Maeght: L'Art contemporain et la Côte d'Azur, un territoire pour l'expérimentation, 1951-2011 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Le Temps de l'écoute, pratiques sonores et musicales sur la Côte d'Azur des années 1950 à nos jours |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Brooklyn Blowhards The band which takes Ayler out to sea on the whaling boats, and which has been mentioned a couple of times in these pages, have a new CD out. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

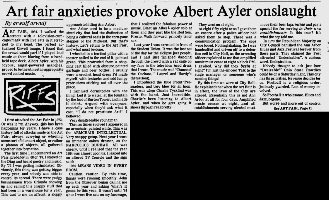

It features four Ayler tunes, ‘Bells’, ‘Dancing Flower’, ‘Heavenly Home’ and ‘Omega’ alongside traditional sea shanties and is due for release on 6th April, with a party at Joe’s Pub, New York. Further information on Jeff Lederer’s little(i)music site and samples are available on soundcloud. * Spring cleaning I’ve been trying to clean out my computer and came across a couple of items which I don’t think I’ve mentioned before. One is a version of ‘Truth Is Marching In’ played by Bert van Erk on the double bass. The other is this newspaper clipping from The Michigan Daily of 24th July, 1985. Hardly news, I know, but I hate to throw anything away. Besides, ‘Art fair anxieties provoke Albert Ayler onslaught’ is a great headline. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

And finally ... Thanks to Dirk Goedeking.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The news from January to March, 2016 is now at peace in the Archives. ***

May 1 2016

New Hat Hut CD |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I mentioned this last month and Hat Hut Records kindly sent me the full details of their new release, including the track list: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

So what we have here is The Hilversum Session with three tracks from The Copenhagen Tapes. The history of The Hilversum Session is interesting: originally released in November, 1980 by George Coppens on the Dutch label, Osmosis, there was then a subsequent CD release on the Coppens label before it was transferred in 2007 to ESP. The ESP version is still available, but presumably this Hat Hut release (approved by the Ayler estate) will eventually supplant it. The inclusion of the three tracks from The Copenhagen Tapes is also of interest. As far as I know these have only ever appeared on The Copenhagen Tapes, which is, of course, no longer available. So, Hat Hut should be congratulated for returning these to the catalogue. The other tracks on The Copenhagen Tapes came from a session at the Café Montmartre recorded on 3rd September, 1964 and were also included in the Holy Ghost box set (which now resides in some kind of legal limbo). European Radio Studio Recordings 1964 by the Albert Ayler Quartet should be released later this month and I now just have to decide where to place it in the Discography. * New York Is Killing Me: Albert Ayler’s Life and Death in the Jazz Capital The current print issue of The Pitchfork Review includes this article, ‘New York Is Killing Me: Albert Ayler’s Life and Death in the Jazz Capital’ by Mark Richardson, which is also available online. As well as giving a useful overview of Ayler’s career and his connection with New York, it also includes some photos of places in the city, relevant to the Ayler story, showing how they look today. Thanks to Kees Hazevoet, and the facebook Ayler group for the link. * Baltimore Requiem A collaboration between alto saxophonist Jarrett Gilgore and MC Eze Jackson, Baltimore Requiem was premiered at the Redlining Baltimore event at the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of African American History and Culture on 13th April, 2016. There’s an article by Bret McCabe which gives the background to the work, including the information that it incorporates “a few field recordings he made from local anti-police brutality protests last April and a sample of poet Amiri Baraka reciting ‘Black Art’ with saxophonist Albert Ayler, trumpeter Don Cherry, and drummer Sonny Murray, from Murray’s 1965 album, Sonny's Time Now.” Which is why it gets a mention here. I have to admit I had a struggle identifying the Ayler clip (which comes in around the 2:30 mark) but I think that’s just me being half-deaf and old. The video of the performance and Eze Jackson’s lyrics are available here, and it’s also on youtube.

|

||||||||

|

Concert Reviews I have to thank Roy Morris for sending me a batch of Ayler-related press cuttings. Most of these were reviews of Spirits (aka Witches & Devils) but there were a couple of pieces by Elisabeth van der Mei from Coda which mentioned Ayler concerts. Rather than just linking to these, I thought I’d add them here, since the first is a reminder that despite the sterling work done by all the record companies unearthing Ayler tapes, there were some intriguing Ayler line-ups that were never recorded. And the second review adds a little more information to the troubled history of Don Ayler.

1. The Albert Ayler Quintet (Don Ayler (t), Charles Tyler (as), Albert Ayler (ts), Joel Freedman (cello), Charles Moffett (later replaced by Ronald Shannon Jackson) (d) at the Astor Place Playhouse, New York, February 1966. From Coda (April / May 1966 - p.25) . . . 2. The Albert Ayler Quartet (Albert Ayler (ts), Call Cobbs (p), Bill Folwell (bass guitar) Beaver Harris (d) at the Café au Go Go, New York, July, 1968. From Coda (November/December 1968, p. 39) . . .

(There's a rather sad postscript to this. I'd already added one article by Elisabeth van der Mei to the site (‘The New Music Scene’ from the May 1967 issue of Coda, and you can also read the rest of her article from the May 1966 issue from which the Astor Place Playhouse review above is taken) but I was checking the spelling of her first name since it's sometimes printed with an 's' sometimes a 'z', when I came across this obituary on a Grateful Dead site. Elisabeth van der Mei died last year at the age of 79.) * Joe Rigby and more about Don Ayler Roy Morris also alerted me to this performance by Joe Rigby with Andrew Bemkey from 7th July, 2014 on youtube.

|

||||||||

|

And I make no apologies for posting this again. It’s the clip of Don Ayler singing, taken from one of Richard Koloda’s interviews with Don. It’s had several views on youtube (far less than if Richard had placed a comical cat on the table) but few comments. However, the following appeared a few days ago, which prompted this repeat. It’s from ‘jltrem’ and reads: “I worked for the Ohio Department of Mental Health for nearly 32 years and had Don as a patient for a number of years. He was a gentle soul. Sadly, his musical abilities had all but faded away. He passed away at the hospital in 2007.”

|

||||||||

|

And a final note about Don. Dirk Goedeking sent me a review of the Fondation Maeght concerts from the French magazine, Jazz 70. The list of musicians playing at the two concerts concludes with the following note: "Donald Ayler (tp) ill, couldn't come to France". Which must have been the official story. However, I remember Richard Koloda telling me that Don had said Albert had actually invited him to make the trip but Don had turned him down because he had no interest in playing “rock’n’roll”. * Gato Barbieri (28/11/1932 - 2/4/2016) |

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

And still in unapologetic mood, I break the self-imposed rule regarding mentioning the deaths of jazz musicians on this site unless they have some tangible connection to Albert Ayler. If ever I’m asked who my favourite saxophone player is (which, I admit, does not happen that often), if I’m in a perverse mood I will say Adrian Rollini or Fess Williams or Al Doctor. But, if I’m serious, I won’t say Albert Ayler, or Ornette Coleman or John Coltrane, I’ll say Gato Barbieri. There was something about his sound that I just loved. Of course, one has to add the rider (and perhaps this is an Ayler connection) that he sold out. I remember buying a 12” single from a record fair of Barbieri playing ‘Poinciana’, taken from some album he’d made under the aegis of Herb Alpert, and it was so bloody awful that I ignored him from then on. But, his early work, especially with the JCOA, and the four ‘Chapter’ albums he made for Impulse, remain among my favourites. As does this duet with Dollar Brand, recorded in 1968.

|

||||||||

|

Among the obituaries, there’s one in The New York Times and Richard Williams has posted his assessment of Gato Barbieri on his ‘The Blue Moment’ blog. * And back to Albert Here’s the Lewis Jordan Trio at Bird & Beckett Books, San Francisco, with an Albert Ayler tribute from 13th March, 2016:

|

||||||||

|

June 1 2016

Albert Ayler Award Steve Tintweiss posted the following on the facebook Ayler group: ‘Albert Ayler 80th birthday coming up very soon. July 13 marks the date. Announcing here the first “Albert Ayler Award” given to a Masters of Music graduate in Jazz Performance or Composition at Aaron Copland School of Music at Queens College. It will be the first for the next 18 years to be presented at the June 2, 2016 Graduation Ceremony. I'm pleased to be able to sponsor this annual recognition.’ So, congratulations to Steve for sponsoring the award, and congratulations to tomorrow’s winner. Steve’s post did prompt the following comment from Peter Selover, which I thought worth repeating here: ‘I am delighted to hear about the establishment of this award, but in my heart I wish that a Cleveland based award could also be developed. If it is to be linked to a specific school, it may need to be Cleveland State as opposed to a place like the Cleveland Institute of Music which is almost exclusively involved in Classical music. I am certain that you have put a considerable amount of effort into getting this off the ground, and I am in no way critiquing your efforts . . . . . this is a Clevelander thinking out loud. Albert is not that well known in his own home, and a version of the Queens College award here could help rectify that tragic oversight. Albert belongs to the world, but Cleveland and New York have the primary responsibility for tending to his legacy, and sadly . . . . . I must admit that we have not done enough here. I have neither the clout or the financial resources to become a player in creating such an award here . . . . . but my devotion to Albert is manifested in quiet and intimate routines . . . . such as my weekly visits to his grave, and my tenacious efforts to personally cultivate new fans for his music . . . . . . . . . . but my confession about Cleveland’s somewhat anemic relationship with Albert’s memory is not rooted in pessimism. We have handled our reverence for the years that Langston Hughes lived here quite well, but the mainstream awareness of that was the result of decades of sustained education about Cleveland’s impact on the evolution of Langston’s greatness. So, I think the key here is more information about Albert’s greatness finding its way into our schools and appearing more often in the words of our living musicians . . . . Joe Lovano is a hero on that count, he often speaks with great affection about his own father’s relationship with Albert. I guess what I am trying to say is that if the people that you worked with in developing this new award have any interest in lighting a fire under our ass here, those efforts would be greeted with profound appreciation by a small . . . . but fiercely loyal fan base for Albert, here in his hometown !!!’ * The Hilversum Session Following on last month’s news of the rerelease of The Hilversum Session by Hat Hut (under the title, European Radio Studio Recordings 1964) comes this fascinating article by Bert Vuijsje (who was present at the session) originally published in the Dutch weekly newspaper Vrij Nederland on 5th December, 1964. Mr. Vuijsje sent a copy of this article to his friend, Kees Hazevoet, and Kees took the time and trouble to translate it into English, before sending it on to me. So, many thanks to them both. A recording session with Albert Ayler and Don Cherry by Bert Vuijsje It is Monday, November 9, 8 pm at VARA Studio 5. Tenorist Albert Ayler, trumpeter Don Cherry, bassist Gary Peacock and drummer Sonny Murray are going to record for Jazz Magazine i. The others present – the editorial team of Jazz Magazine, impresario Paul Karting and a handful of Dutch jazz musicians – anxiously await what is to come. Last weekend Peacock suffered three bouts of stomach trouble and on Sunday afternoon Murray demanded an extra 50 guilders for the performance in Alkmaar. Karting refused and the group therefore played without a drummer in ‘Extase’ at the Bergerweg. Tonight the prospects are better: at 7.15 pm the whole group was already present in the studio to install the instruments and do some warming up. The music of this quartet does away radically with a number of traditional conventions that most avantgardists have only reluctantly undermined so far. The intimate relation between theme and improvisation that they maintain is emotional, the mood of the theme influences what is to follow. There still is a tempo, even though it often changes, but there is no division into bars anymore. The drummer divides the time and that is all; the usual partition in more and less accentuated beats has been abandoned. The bassist does not have to play or suggest four to the bar and neither is he restricted to the harmonies associated (either explicit or implicit) with the tune’s theme. Hence, the soloists have a heretofore unknown freedom, which – other than one may think – does not make their task easier. When the theme has been stated they are confronted with a total blank that has to be filled purely with their own ideas. The comfortably and routinely ‘running the changes’ (playing the tune’s harmonies) is not possible anymore and everything has to come from their own inspiration. At 8.10 pm the recording engineer says he is ready to go. A short piece is played to check the balance. Then the group starts off with ‘Angels’, one of the five Ayler originals that will be played. Don Cherry hardly moves, only during high passages he sometimes bends his knees. During his career he has often been the modest and lyrical counterweight of a dominant leader (Ornette Coleman, Sonny Rollins). With this quartet he again seems to take up that role. He alternates between fast and nervous runs of notes and quiet and strongly melodic lines. Ayler’s violent movements are reminiscent of Johnny Griffin. Like Griffin he gives the impression of permanent and complete involvement. He employs an unusually strong and slow vibrato that, paradoxically, reminds one of the first attempts – some forty years ago – to play jazz on a saxophone. Completely contemporary are Ayler’s tonal experiments, in which he is clearly influenced by Coltrane and, especially, Rollins. Peacock’s amazing speed, the effortless way in which he uses double stops and the sheer unbelievable certainty with which he plays even the highest notes, demonstrate that the technical advances in playing the bass in the US during the past few years have proceeded even quicker than was suspected in Europe. He is an exceptionally gifted accompanist; without imposing his ideas on the soloist, Peacock supports him with inventive background figures of great beauty. Sonny Murray constantly makes strong movements with the mouth and accompanies himself with a piercing buzz that becomes irritating after a while. After the second piece, ‘C.A.C.’, the result of this first set is played back and listened to. Don Cherry lights a cigarette and sits down on one of the covered hammond organs. Ayler restlessly walks back and forth. Peacock leans on a piano and stares out of the window. Murray listens attentively with his head bent. The music coming from the loudspeakers is much better balanced than the live performances that we heard during the past days (the term ‘studio quality’, often used in advertisements for cable radio ii, proves to be rather misleading). It now becomes even clearer how sublimely Peacock accompanies; with a much reduced volume, Murray’s obtrusive playing becomes more bearable. The playback ends with a long and resonating bass note. Ayler descends from the control room. Cherry, who appears to be an enthusiastic amateur pianist, plays Thelonious Monk’s ‘Light Blue’ on the piano. Murray walks back to the drums, making some jerky dance steps along the way. Peacock again installs his bass into a custom made little plank with slots. As more music has to be recorded, Cherry swaps the piano for his pocket-trumpet. iii The third number is ‘Ghosts’, a theme that could easily become a nursery rhyme. Murray soon loses one of his sticks, which Ayler patiently returns to him. Herman Schoonderwalt and Ruud Jacobs iv are listening with some amusement to Ayler’s musical force. Bassist Arend Nijenhuis v listens seriously and apparently is completely absorbed. When the number is finished, only Nijenhuis applauds, causing Don Cherry to look over his shoulder quite suspiciously. During the next number, Don Cherry’s ‘Infant Happiness’, Sonny Murray loses a stick four times vi. At 8.55 pm another break is taken. Ayler goes upstairs [to the control room]. Cherry plays some more Monk piano, now with Murray in the upperhand. There is less attention for the recorded music than the first time. Paul Karting tells me that Cherry, after the concert in Rotterdam on Saturday, played piano for two hours, with local musicians on bass and drums. Murray starts packing his borrowed drum set vii, but two more numbers are still to be recorded, so he assembles it once again. Don Cherry plays, accompanied by Peacock, a slow and fluent melody. His technique has improved considerably since he started with Ornette Coleman. The last set is ended with an as yet untitled Ayler original. Cherry’s solo in this number shows to be largely a repeat of what he just played during the intermission. Apparently, even in free jazz an original improvisation slowly becomes a standard solo. At 9.35 pm, the 40 minutes of music that are needed are on tape. Peacock and Murray are really packing now. Cherry puts on his grass-green woolly hat and takes out a little bamboo flute. Ayler wears a light yellow Russian hat. Jazz Magazine editor Kees Schoonenberg tells that during the session Paul Godwin entered the control room and cried out: ‘That bass is so totally in tune!’, and went to call the other members of the Hollands Strijkkwartet [Netherlands’ String Quartet]. The musicians still have to be paid, which gives rise to some confusion as to whether or not Ayler has filled in an allocation sheet. Tomorrow the members of the quartet will each go their own way. Like in the US, there is very little work for these kinds of groups in Europe. Murray is going to make a record in Copenhagen, Cherry travels to London and Peacock is going to visit a doctor in Brussels. Only Ayler does not have definite plans yet. There is extensive farewell saying. Ayler travels back to Amsterdam with us. On the way he tells with some pride that Coltrane played his last LP ‘Spirits’ for the full 40 minutes. Ayler does not seem to like Mingus at all: “Much too commercial. I never understood what made Dolphy play with him. Miles, Rollins, Coltrane, they know who’s playing”. Although two Danes played on his first record, he now could not work with European musicians anymore. He tells that he lived in Harlem for six months (‘do you know the word tension?’), and that most musicians did not have the guts to visit him there. “Only Ornette sometimes passed by; he had a girl there”. His composition ‘Ghosts’ originated during that time. Suddenly he asks what kind of records I have. My answer (a lot of Parker, some Mingus and Coltrane) seems to disappoint him. Apparently, Ayler does not belong to those musicians that have much interest in older (nowadays a rather relative adjective) jazz forms. At 10.45 pm we drop Ayler at his hotel at the Geldersekade. He is going to sleep some and perhaps later visit the Sheherazade viii. Around 11.30 pm it proves to be depressingly empty there and we return home in a somewhat disenchanted mood. _____ i During the 1960s, Jazz Magazine was a weekly program on VARA-radio. (return to text) [Originally published in Vrij Nederland of December 5, 1964 * New Reissues Thanks to Dirk Goedeking for letting me know that The First Recordings Vol. 2 is due for release on vinyl this month on the Jeanne Dielman label. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

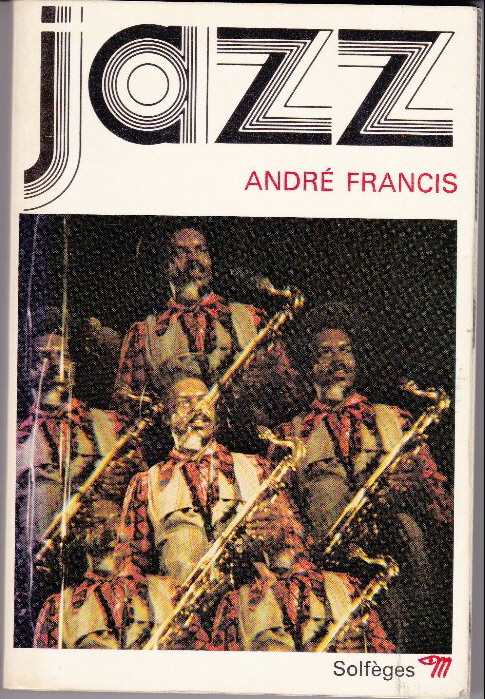

Dirk also came across a couple of other reissues on the Skokiaan label - Ghosts (CD) and Sonny’s Time Now (CD and vinyl). These don’t seem to have filtered down to the regular online shops, but they are listed on the Clear Spot site as due for release on 25th of this month. * Some other stuff Dirk also sent me this cover from an edition of Jazz by André Francis. This was originally published in 1958 and has gone through numerous editions, some translated into English, so I’m not sure when this one appeared, but presumably after 1970. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

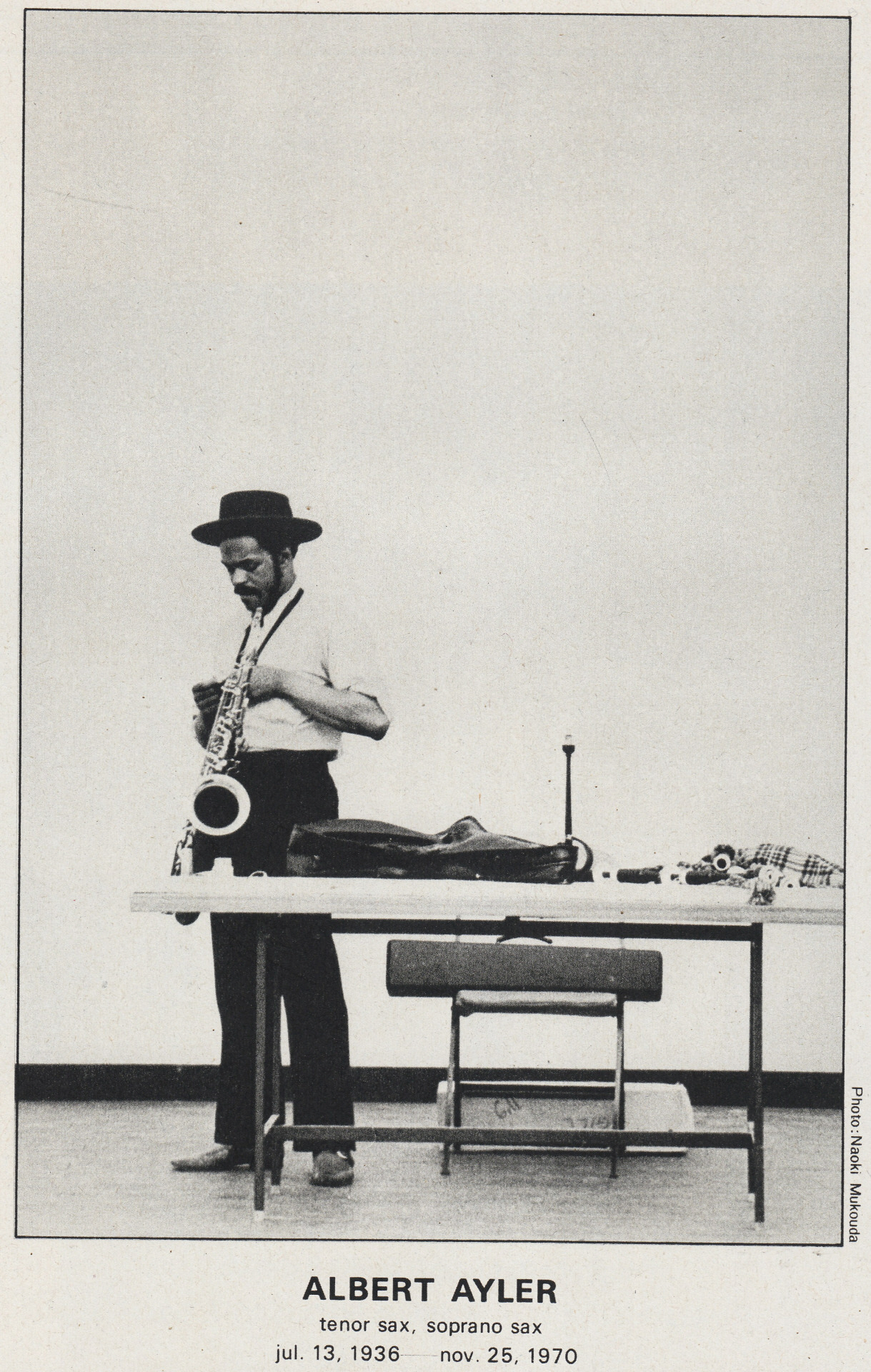

And, staying with photos from the Fondation Maeght, here’s one taken by Naoki Mukouda, which Pierre Crépon came across: |

||||||||

|

|

And links to a couple of items I found: A review of a concert by Diamanda Galás from The New York Times of 12th May in which she “turned a wordless Albert Ayler melody, ‘Angels,’ into soaring phrases that merged Ayler’s saxophone vibrato with operatic style.” And an article about graphic artist, Nate Kitch, which includes the following about how he developed his distinctive style: ‘It was through experimenting during his degree that Kitch developed his digital collage style and gained himself a prestigious Association of Illustration (AoI) Award for New Talent after submitting work from his final year project. He recalls working on a piece about jazz musicians, specifically on a favourite musician of his named Albert Ayler. “As I was tracing him I thought ‘what would it look like if I just cut him out and stuck him on the image?’” Kitch remembers. “So I just cut him out and stuck him on the image and thought, oh that’s pretty good, and from then on, I thought this is definitely the way I should work.”’ * And finally ... This began with a post on the facebook Ayler group from David Bohn saying that Albert Ayler was mentioned in an episode of the TV series, Scorpion. Turned out it was in the second season finale, but since we’re a bit behind over here in the UK I had to wait till last Saturday to record it. Anyway, here’s the clip. Mispronounced as ever, but I think it ranks up there with Shadow Wilson’s namecheck in the latest Mission Impossible film. |

||||

|

*** News from 2004 (January - June) 2004 (July - December) 2005 (January - May) 2005 (June - December) 2010 (January - June) 2010 (July - December) 2011 (January - May) 2011 (June - September) 2011 (October - December) 2012 (January - May) 2012 (June - December) 2013 (January - June) 2013 (July - September) 2013 (October - December) 2014 (January - June) 2014 (July - December) 2015 (January - May) 2015 (June - August) 2015 (September - December) 2016 (January - March) 2016 (July - August) 2016 (September - December) 2017 (January - May) 2017 (June - September) 2017 (October - December) 2018 (January - May) 2018 (June - September) 2018 (October - December) 2019 (January - May) 2019 (June - September) 2019 (October - December) 2020 (January - April) 2020 (May - August) 2020 (September - December) 2021 (January - March) 2021 (April - July) 2021 (August - December) 2022 (January - April) 2022 (May - August) 2022 (September - December) 2023 (January - March) 2023 (April - June) 2023 (July - September) 2023 (October - December) 2024 (January - March) 2024 (April - June) 2024 (July - September) 2024 (October - December)

|

||||

|

Home Biography Discography The Music Archives Links What’s New Site Search

|

||||