|

Music Is The Healing Force Of The Universe The Inconsistency of |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

August 1 2021

Juini Booth (12/2/1948 - 11/7/2021) |

|

|

Arthur Edward Booth, bass player with several notable bands, including the Sun Ra Arkestra and Tony Williams’ Lifetime, has died aged 73. A man of several names, one of which was in these pages for one performance with Albert Ayler, a performance which was filmed by the famous documentarians, D. A. Pennebaker and Richard Leacock, at the Albright-Knox Auditorium in Buffalo, N.Y. on 9th March, 1968. It was filmed for a television documentary, ‘Who’s Afraid of the Avant-Garde?’ which was broadcast on 21st April, 1968, but, unfortunately, the Ayler footage did not make the cut. There’s a brief obituary of ‘Junie’ Booth on the Pitchfork site, and further information on wikipedia. He was born in Buffalo, which perhaps explains why he was part of the Ayler group on that one occasion, and there may be more information at the Buffalo News, which, at the moment, is blocked to European browsers (?). I have to thank Kees Hazevoet for letting me know about Mr. Booth’s passing. * Istanbul not Constantinople Coincidentally it was Kees Hazevoet who kicked off a search for information about Ayler’s Buffalo gig back in February, 2012. A couple of years later, November, 2014, there was a follow-up item about the extensive film archives of D. A. Pennebaker and a possible search for the missing Ayler footage. And the rest is silence. There are items which we know exist, such as the Fondation Maeght documentary, but which we are not allowed to see. And then there are items like the TV programmes from Buffalo and the London School of Economics, which are, effectively, lost. But that does not stop the speculation and I’m sure there are still people out there who can’t believe that the State Broadcaster with ruthless efficiency taped over Ayler’s only performance in Britain with an episode of Terry and June where presumably Terry did something wrong and June found out about it and hilarity ensued. Which brings us to this: Early last month Johann Haidenbauer emailed with a link to the Radio Jazz Copenhagen site which includes a large amount of material (345 hours worth in fact), among which are some programmes about the Copenhagen Jazz Festival, including extracts from the one in November, 1966. Skip down the page and you’ll find ‘Historien om Copenhagen Jazz Festival #1, Ole Matthiessen’, which is described thus (translated by google): “The story of Copenhagen Jazz Festival 1: 2 Around the 1:31:00 mark, to 1:41:45, you’ll find an extract of an Albert Ayler live performance. One assumes from the Copenhagen Festival, recorded at the Tivolis Koncertsal, Copenhagen, Denmark on 11th November, 1966 and broadcast on Danish radio. Except it isn’t. At least it is not part of the ‘Copenhagen Concert’ which is on this site. At which point you start to think, ‘Is this something new? Perhaps a lost tune from Copenhagen?’ At which point I thought I’d better check the Stockholm concert of the day before, and there was the tune, ‘Omega Is The Alpha’, and a similar running time. To my ears (rather, ear) the two tracks sounded the same, but I don’t trust my ear, so I consulted an expert, Dikko Faust in New York. He couldn’t be certain they were the same, but did provide this rundown of the two ‘Omegas’: |

|

|

|

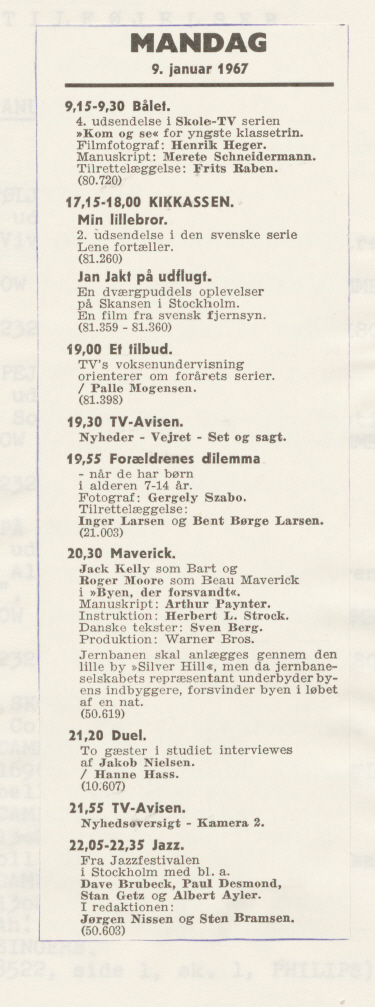

Which I thought was pretty conclusive in itself, given the closeness of the timings, but Dikko wanted a second opinion and so we passed it on to Sean Wilkie in Wales. He replied with this: “Wow! What an amazing performance of Omega Is The Alpha. This may be the gold standard for me going forward. Patrick, you’re correct. It certainly is the same performance – on the Radio Programme - as the Stockholm version I have on the ‘old’ Hat hut Stockholm / Berlin (single) CD. There’s some sonic reproduction difference which a better bluffer than I would describe as higher ends and lower frequencies. I compared them by listening through a few seconds at a time before repeating those seconds on the other version. I’d compare it to finding 32 specific matches on two very similar fingerprints. The hardest bit was Beaver Harris’ spot where the difference between the sound of the two ‘versions’ (Dolby off vs Bias Boost??) made me momentarily doubt the force of the previous 25 matches on the two ‘prints’. But I managed to match Beaver as well, once my ears caught on. (Apologies for all these forensic police work metaphors). There’s also the double-tap? microphone bumping? at 0.51 on the CD version (ca. 1.31.50 on the radio show) and a couple of other anomalous sounds that match up. Marvellous. Sean PS Perhaps the radio broadcast better emphasises Samson, so higher frequencies up (Dolby off)? What a solo by him, what a beautiful handover to Harris …” Right, so I’m happy, but Johann still isn’t. How did an extract from the Stockholm concert end up in a programme about the Copenhagen Festival? Now I’ve seen The Bridge so I’m not surprised at this cross-pollination of jazz recordings in Scandinavia, especially since a programme about the Stockholm concert was shown on Danish TV on two occasions, 9th January and 6th February, 1967. |

|

|||||

|

Ultimately we are in the hands of the Archivists, and sometimes mistakes are made and what is recorded in Stockholm is labelled Copenhagen. To which Johann replies, (I paraphrase), “But what evidence is there that what has been released as the Stockholm concert, was actually recorded in Stockholm.” We are reduced to quoting Yeats: “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold.” * NYEAEC Back on safer ground. Hathut have released their version of New York Eye And Ear Control (New York Eye And Ear Control, Revisited). The Walking Woman is relegated to a cameo and this release is firmly branded as an Albert Ayler album. Chronologically it was the second of the trilogy of great collective improvisations of Free Jazz, preceded by Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz (recorded December, 1960) and followed by John Coltrane’s Ascension (recorded June, 1965), New York Eye And Ear Control was recorded in the home of Paul Haines on 17th July, 1964. Click the picture below for further details of the latest release. |

|||||

|

|||||

|

Michael Snow’s New York Eye And Ear Control is still available on youtube. And there’s a new biography of John Tchicai by Margriet Naber, John Tchicai: A Chaos With Some Kind Of Order, which is previewed in The Wire. * Yusuf Mumin Last December there was a piece about Yusuf Mumin and the Cleveland avant-garde, linked to an article (and playlist) on the Wire site. In his essay Yusuf Mumin mentioned the following: ‘Before I heard Albert Ayler play in person, his dad Edward Ayler, a longtime friend of my family, had brought my mother a copy of Albert’s album Bells. Albert was not around town much, he was in New York or Europe. I in fact only saw him once, in a Cleveland concert he held at WHK Auditorium in February 1967. Pierre Crépon let me know that the recordings referred to above are now available on bandcamp. |

|

|

Pierre has also reviewed the album for the current issue of The New York City Jazz Record, which is available for free download here. Pierre’s review is on page 20. * Spiritual Jazz A couple of articles about Spiritual Jazz mention Albert Ayler. One by Daniel Spicer in The Quietus is prompted by the reissue of an Alice Coltrane album, Kirtan: Turiya Sings. The other is a list by Louis-Julien Nicolaou of ‘From Coltrane to Pharoah Sanders,the Ten Apostles of Spiritual Jazz’. Albert Ayler comes in at No. 2 with In Greenwich Village. There’s also an article at Il Manifesto: ‘Jazz, the miraculous cure of the spiritStories / The link between music, illness and therapy through albums, books and comics. From “Music is the Healing Force of the Universe”, the album by Albert Ayler, to the beneficial virus of “Mumbo Jumbo”, the visionary novel by Ishmael Reed. Watch out for “Abbott”, a graphic novel whose protagonist, an investigative journalist, soothes the pain of her partner's death with the art of John Coltrane.’ And - a tenuous link - Dirk Goedeking sent this: |

|

|

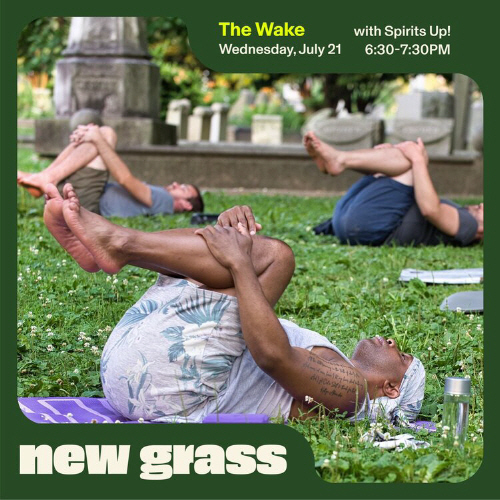

Part of a new initiative at The Woodlands, Philadelphia: “This summer, Ars Nova Workshop, The Woodlands, and Spirits Up! will host a series of free outdoor yoga and mindfulness sessions paired with live music. We will mold mindfulness, meditation, and movement into each of these sessions while paying homage to many of the foundational forces in Black Liberation Music, such as Alice Coltrane, Pharoah Sanders, Albert Ayler, and John Coltrane.” And there’s an article by Peter Crimmins, ‘Meditation for liberation in a West Philly cemetery’, at WHYY. To counter all this healthy mindfulness, Dirk also sent this: |

|

|

Correspondence Steve Tintweiss writes... “All About Jazz” podcast included two tracks from “MarksTown” The Purple Why 1968 at St Mark”s Church Biafra Benefit concert. It features a Mark Whitecage tenor sax solo on Ramona I Love You, and rare trumpet work by James DuBoise. Bassist Steve Tintweiss sings How Sweet? with Judy Stuart backup vocals and Laurence Cook on drums. IDM003 on new INKY DoT MEDIA label also includes a set from Town Hall a month later with baritone saxophonist Trevor Koehler and singer Amy Sheffer added to the ensemble. Meanwhile, Richard Koloda asks “if anyone has a clue as to the age of Mary Parks?” Kees Hazevoet sent a link to a site which then links to My Name Is Albert Ayler on youtube. And Dirk Goedeking sent a link to an illustrated review by Chris Fischer of the Holy Ghost box set, which is rather odd. Here’s a sample: |

|

|

National Anthems With the Olympics in full swing we are reminded yet again of how exceptionally turgid and downright depressing is the national anthem of ‘Great’ Britain. I think that all sportspeople fortunate enough to win a gold medal should be allowed to nominate La Marseillaise as their anthem of choice to be played while they stand on the podium. There’s a celebration of La Marseillaise here, which has Albert Ayler’s version at No. 2. And here’s a particularly rousing version:

|

|

And finally . . . Another one from Dirk: |

|||

|

|||

|

What’s New April to July 2021 is now in the Archives. *** September 1 2021

A Tale of Two Cities It’s the 1966 European Tour again. 1. Munich Dirk Goedeking spotted this on the facebook Ayler Group page. Christer Fredriksson asked the question, ‘Which is your favourite version of Truth Is Marching In?’ and hidden among the replies was the following from Jerry Bauer: “The very best version I will ever be able to hear was when Albert with his group walked in at ‘Domicile’, Munich, 1967, by surprise and intoned the piece. To have heard Albert live, Beaver Harris and brother Don right behind him, was a huge adventure without comparison.” He then added: “When we first met I took Albert to my place and we were listening to Oum Kaltsoum and Arabic music all night long. The next evening we had a party at my late brother Khalil Sabir’s pad, who by chance a schoolfriend of Albert’s from Cleveland, Ohio, with the entire band. We listened to his record ‘Bells’ (Opaque Red Vinyl) but did not really know what to make of it. That’s why we all finally marched to the local Jazz club and just took over.” Then I came in with: “There's a gap in the 1966 European Tour when it has always been rumoured that the Ayler group recorded a TV programme in Munich. That's a session without an audience and not part of the Tour. This is the first time I've had any other indication that Ayler was in Munich (I think you mean 66 and not 67) and I wondered if you could expand on the story and maybe you can remember if the TV recording was mentioned.” And Jerry replied: “I doubt any TV-recording in Munich very much. I met Albert at the ‘Domicile’ - you`re right it was in 1966 - and the local house band was on: Don Menza (ts) and my late close friend Hartwig Bartz was the drummer. At the next break Albert took to him right away. Don [Menza] wanted to sell Albert a mouthpiece he himself had designed but Albert told him that he was quite satisfied with his own equipment. We got acquainted and stayed together at our pad listening to Oum Kaltsoum on my new tape recorder. Since the club owner Ernst Knauf who did not like Free Jazz had not been ready to give Albert and his group a sudden chance for a sudden appearance we had a private party the next night. That lead to the startling take-over. All dammed aggression let loose. I was sitting only about five meters away from Don and he nailed me with his sound right through the wall behind me. Albert played some sounds never heard on saxophone - never before and never after. My friend Hartwig was afraid that Beaver would wreck his drum set. The ghost was loose, some drunkards at the bar fell down, glasses broke, Don [M] was running back and forth all over the club. With all his mouthpieces he could never have produced a similar sound. After this musical invasion nobody had dared to get on stage to continue. And so I went to have a beer with Albert and Beaver to the only club still open in Schwabing. In our conversation Albert expressed a yearning for death that Beaver severely disagreed with. The next thing I heard of Albert was that he was drowned in the Hudson river. RIP, dear friend!” And Dirk added a couple of grace notes to the proceedings. The wikipedia page for the Domicile club, and ‘a record by by the aforementioned Oum Kaltsoum from 1964’ and concluded with the following: “Unbelievable, 55 years later someone just answers a simple question: What is your favourite version ...?” The Munich TV recording session has been one of those constant mysteries in the Ayler saga. We’re no further forward really, but at least now we have a sighting of Albert Ayler’s band in Munich in November, 1966. There is a gap in the European Tour - 3rd November - Berlin. Presumably the 12th was a day off, but the 4th to the 6th is the most likely spot for the trip to the SWF Television Studio in Munich (and the Domicile club). Zurich and Baden Baden have also been suggested as possible venues for other concerts, but no evidence has turned up. And there is nothing from the Munich TV recording - which Bill Folwell had a clear memory of, whereas he swore blind he’d never been to Bordeaux, despite the video evidence. Personally I think the TV recording took place and, now we have confirmation of the Ayler group in Munich, there’s no reason to question that it happened there. Why else would the band have been in Munich? But then, why are there no stories attached, no faint memories of seeing Ayler in a studio setting, no rubbish recordings from microphones held up to television speakers and captured on reel-to-reel tape machines. The non-existent and never-seen video from the London School of Economics has generated an immense amount of material, articles in newspapers and magazines, personal memories of members of that lucky, lucky audience. But from Munich, nothing. Which brings us to the second city. 2. London How many times have we cursed the name of Billy Cotton Jr. in our nightly prayers? The BBC executive who has been accused of walking down his corridors of power, hearing the sublime sounds of the Albert Ayler Quintet in full flow at the London School of Economics on 15th November 1966, and demanding that the music be stopped and the tapes wiped, never to be allowed on the airwaves of the State Broadcaster. Turns out, owd Billy Jr. might be innocent. Dave Jackson put me onto this, pointing me in the direction of the Matchless Recordings site, where there are two supplementary chapters to Eddie Prévost’s book, An Uncommon Music For The Common Man. Both are available as free pdf downloads and both are well worth reading, but it is the shorter of the two which concerns us here: ‘Unholy Ghosts - conspiracy theories and Albert Ayler’. According to this, there is a very good case to be made for the Ayler concert at the L.S.E. not being recorded at all. That, in fact, the plug was pulled mid-performance and there was, ultimately, nothing to be broadcast and not a lot to be wiped. Looking at the other accounts of the concert, one can believe such a hasty decision. But, although Humphrey Lyttelton obviously had no time for the music (oddly his greatest opprobium is reserved for the classically-trained Michel Samson) he does not mention the recording being stopped and repeats the well-loved tale: “The men upstairs at the BBC took one look at the programme which we recorded at the L.S.E. and decided that it was not suitable for transmission. A year or two later, in an act of criminal negligence, almost all the irreplaceable stock of BBC 2 jazz recordings—perhaps the most comprehensive collection of ‘in action’ jazz recordings in the world—were wiped off in a routine exercise to conserve video-tape.” I remember in the early days of this site, writing to the BBC to ask them to nip down and have a look in their basement to see if they had the Ayler L.S.E. videotape, and I received a nice reply saying, ‘sorry, no, nothing’. I wonder how many other people have done that over the years and now we all have to adjust our thinking, no longer ‘wiped’ or’ lost’ but now just, ‘stupidly abandoned’. When I root in my memory of Jazz 625 and Jazz Goes To College programmes, they all seem rather staid and conventional. I think the only time it ever got raucous was when Alex Welsh’s drummer, Lennie Hastings, shouted “Ooyah ooyah” or some such at the end of his drum solos. So, to be confronted by the Albert Ayler Quintet - at the fag end of their European tour, which hadn’t gone that smoothly, compounded by the trouble getting into the country and their consequently late arrival at the gig - and that glorious noise that they’d probably never encountered before, it seems quite feasible that the engineers and the man in charge of the recording would have thought “No, I don’t think so,” and would have pulled the plug. Read the Eddie Prévost ‘chapter’ and make your own mind up (and also be prepared to have your opinion of Evan Parker altered). * Fire Music There’s a trailer for Tom Surgal’s documentary about Free Jazz, which was premiered in September 2018, on youtube which ends with: “In Theaters Sept 2021”. So, there’s something going on there - we shall wait and see what. In the meantime, there’s a recent review of the film by Steve Provizer on the arts fuse and here’s the trailer with the briefest of clips of Albert (I think from Berlin, 1966).

|

|

Dance Balerina Dance I know, I shouldn’t encourage these people, but the picture (and the spelling) caught my eye. On closer examination it turned out to be a teapot, but not one to grace the extensive crockery collection of Hanley Museum. But check this out for a tracklist: 1. All The Things You Are by Tommy Dorsey Now that’s eclectic! |

|||

|

|||

|

More weirdness from youtube YOUR LIFE BLUEPRINT SOUND VIBRATIONS FOR REBEL SATURDAY - ALBERT AYLER Made weirder because the bloke looks a bit like Laurence Fox.

LIST OF FAMOUS BANDLEADERS Described thusly: ‘List of famous bandleaders, with photos, bios, and other information when available. Who are the top bandleaders in the world? This includes the most prominent bandleaders, living and dead, both in America and abroad. This list of notable bandleaders is ordered by their level of prominence, and can be sorted for various bits of information, such as where these historic bandleaders were born and what their nationality is. The people on this list are from different countries, but what they all have in common is that they're all renowned bandleaders. These people, like James Brown and Ray Charles include images when available. From reputable, prominent, and well known bandleaders to the lesser known bandleaders of today, these are some of the best professionals in the bandleader field. If you want to answer the questions, "Who are the most famous bandleaders ever?" and "What are the names of famous bandleaders?" then you're in the right place.’ Albert Ayler makes the list as Famous Bandleader No. 49, not far behind Brian Jones as Famous Bandleader No. 47 and Chico Marx as Famous Bandleader No. 46. * This month’s Ghosts The Lester Bowie Quintet at the Detroit Institute of Arts from 4th September, 1982. And this:

|

|

October 1 2021

George Wein (3/10/1925 - 13/9/2021) Admittedly a peripheral figure in the story of Albert Ayler but I felt I should acknowledge the passing of George Wein, the jazz impresario who started the Newport Jazz Festival (among others) and was responsible for the ‘Newport Jazz Festival In Europe 1966’ tour which included the Albert Ayler Quintet. That, of course, resulted in a number of live recordings of the band, and at least one performance (Berlin) which was captured on film in its entirety. So, thanks George. There are obituaries everywhere, here’s the Down Beat one, and this is Richard Williams in The Guardian. * Munich again Just a quick follow-up to last month’s speculation about whether the Ayler Quintet recorded a session in a TV studio (without an audience) in Munich during that 1966 European Tour. Jerry Bauer’s story placed Albert and his band in Munich (where they didn’t play a scheduled concert as part of the tour) but the TV studio date was still unconfirmed. Dirk Goedeking has now come back with this: ‘I contacted all three public broadcasters: BR in Bavaria, SWR in Baden-Württemberg and SRG in Switzerland. All of them replied, but none of them could help. All I got was a list of what is where in the archives. Only two broadcasts from the Berlin concert in the archives of WDR in Cologne: Proszenium (whole concert) and Jazz zur Nacht (Our Prayer). That's it. One thing for sure: There is and was no SWF television studio in Munich. The reason is simple. Public broadcasters in Germany are operating regionally. BR only in Bavaria, SWR (former SWF) in Baden-Württemberg, etc. (e.g. Radio Scotland may broadcast a program produced by Radio Wales, but they won't have a studio in Cardiff). So either the SWF studio in Baden-Baden or the BR studio in Munich or a Swiss studio in Zürich are possible.’ Maybe we should leave it there. For now. * Fire Music There are more reviews of Tom Surgal’s documentary about Free Jazz, Fire Music, at The Guardian, Stereogum (following the George Wein obituary), and Filmmaker. The latter is headed: “The Parts That Were Left out of the Ken Burns Documentary” - which is nice. The film is only being shown in the U.S. at the moment - full details on the Fire Music website. * Another Archie Shepp title ‘The Way Ahead’ are a Scandinavian band influenced by Albert Ayler, mentioned in these pages a couple of years ago for their album, Bells, Ghosts and other Saints. A concert which they gave in Austria last month is now available on youtube. And, on the same subject (bands influenced by Ayler rather than bands with names taken from Shepp albums), Jeff Lederer’s ‘Sunwatcher’ group has reunited for a new album, Eightfold Path. And a bit different (though Buddhism gets another mention) is a three album project by Stefen Robinson, subject of this article on the WGLT site, which includes the following: “Each of these albums is named after an album by a saxophone player who’s deeply influential to me. The first one is Ornette Coleman. The second one is Albert Ayler. Then the third one is Coltrane.” * And speaking of Coltrane ... A new, live version of A Love Supreme has been discovered and is due for release this month. It’s entitled A Love Supreme: Live in Seattle and here’s one of the tracks:

|

|

|

Belated Birthdays Albert Ayler would have been 85 on 13th July this year and, as usual, I missed it. I also failed to notice this on the Ayler facebook group, posted by the aforementioned Jeff Lederer: ‘Early Ayler birthday celebration today Sat July 10 at the “Peninsula” in Prospect Park Bklyn 3-4pm. Bring your instrument, and a flower.’ |

|

|

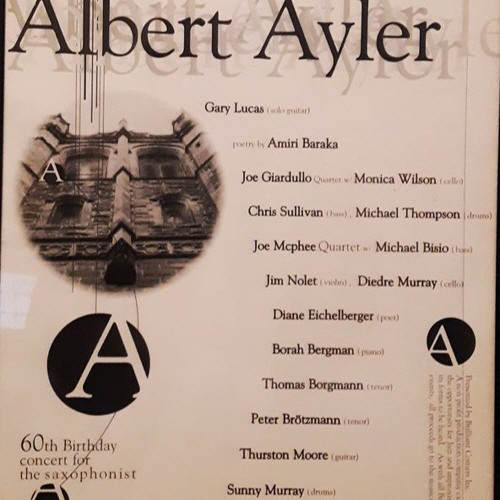

Dirk Goedeking let me know about that one and also this recording of the opening piece (by the Joe Giardullo Quartet) of The Albert Ayler Festival, held to commemorate his 60th birthday in the Washington Square Church in New York on 20th September, 1996. |

|

|

And then there’s this: The City ***

November 1 2021

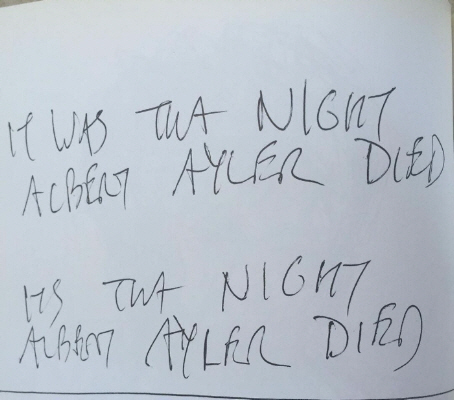

Hat Hut La Cave Tentative news this but if Mr. Uehlinger can pull it off it will be great. This is the current notice of upcoming releases for the Hat Hut label: ‘Forthcoming 2021/2022 releases: Morton Feldman : For John Cage by Judith Wegman & Andreas Kunz; Cat Hope, Decibel; New York Contemporary Five, Copenhagen 1963 „Revisited“; Calato-John Cage, Variations+Four; Ellery Eskelin, Trio New York „Revisited“; François Houle-Marco von Orelli, Make That Flight; François Houle-Joe Sorbara, Hush; Albert Ayler Quintet, La Cave Live Cleveland 1966 „Revisited“; Christopher Fox, Strings.’ Our particular reason to be cheerful is the inclusion of the La Cave sessions previously included in the Holy Ghost box set, which, because of legal shenanigans has ended up in an odd state of limbo. The La Cave sessions took up two CDs in the box and comprised two nights of the Ayler group at the La Cave club in Ayler’s home town of Cleveland, on the 16th and 17th April, 1966. What makes the sessions more significant is that it reveals the group in a state of transition, leaving behind the alto sax of Charles Tyler which had enlivened the line-ups of Bells and Spirits Rejoice, replacing it with the violin of Michel Samson (literally a day or two before the recordings). This became the front line of the band which went on to record the live sessions at Slugs’ Saloon, the European concerts of November, 1966, the various dates in Greenwich Village, and Ayler’s only appearance at the Newport Jazz Festival in June, 1967. Hopefully this music will be back in the world again, soon. * On the other hand It was Dirk Goedeking who spotted the above, while he was wondering what had happened to Hat Hut’s release of Ayler’s final concert at the Fondation Maeght, which had been eagerly-awaited for a while, but which had disappeared from its ‘Upcoming’ list. Hopefully. whatever the problem is, it will be solved. But it sent Dirk into a slough of despond and he sent the following items (perhaps befitting the Ghostly season): “Death By Jukebox - Strange Rock Star Deaths #3” (From 2012, but the jukebox tale never gets old.) A poem by Alan Vega: |

|

|

A one hour broadcast by TSF Jazz radio in Paris from 25th November, 2020, “Albert Ayler, 50 Years Later” (‘Poor Albert, they were never ready for him ... and they still are not.’)

And this postcard of the Staten Island Ferry circa 1970: |

|

|

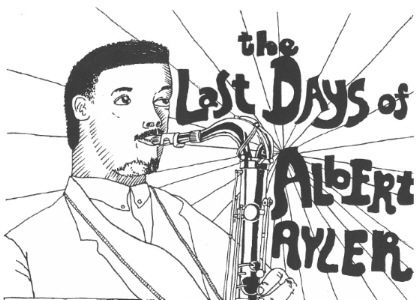

And finally, I will add this from the Internet Archive, Issue No. 24 of Roctober (which I’ve had listed in the Bibliography for a while but whatever it was linked to has died) containing the following in comic (not funny) form: |

|

|

(While you’re at the Internet Archive you might like to check out the article, ‘Albert Ayler in a kilt: The Assassination Weapon, Edinburgh, 1966/7’ by Robin Ramsay, from the Summer 2000 edition of Variant magazine. It brought back memories and not really in a good way.) * Back in Cleveland Good news (at last)! If you go back through the old What’s New pages of this site you’ll come across many mentions of the name ‘Richard Koloda’, usually attached to the phrase ‘who’s writing a book about the Ayler brothers’. Finally, the book is finished (bar a final edit) and Richard has signed up with a publisher and the book should be in the shops in the autumn of next year. Amazingly this will be the first full-length biography of the Ayler brothers to be published in English. At the moment the most useful book about Albert Ayler is the one which accompanied the Holy Ghost box set, which contains essays by Val Wilmer and Marc Chaloin, and a detailed timeline, but (as noted above) this also remains in limbo. Richard began the book as a collaboration with Don Ayler, and the sections on the early life of the brothers in Cleveland, and the later life of Don, after his brother’s death, are particularly revealing. From time to time Richard would send me photos and newspaper clippings and copies of official documents (with a polite notice not to post them on the site) so I hope some of these will make it into the final version. At one time he was also considering including a DVD with the book of an interview he’d filmed with Don and his father, but I don’t think that’s still on the cards. Although it does give me an excuse to include this extract here:

|

|

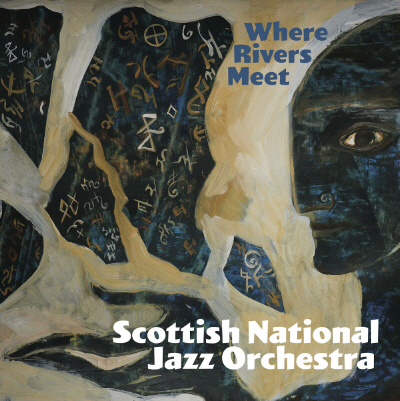

So, many congratulations to Richard, and I’m sure we’ll have more snippets of information and previews in the months to come. In the meantime he is interested in any previously unpublished photos of the Ayler brothers which may be out there. * Albert Ayler: 10 Essential Albums One could ask, why only 10? Or one could question why The Last Album is in there and not Spirits Rejoice and don’t get me started on Music Is The Healing Force Of The Universe (“Along with the equally outstanding and misunderstood New Grass album, Ayler here is taking jazz into a new dimension.”) No, I will just thank Alex Van Looy for pointing me in the direction of this list from the Jazzwise site. And ‘Ghosts: first variation’ from Spiritual Unity also just makes it in at No. 10 on this Classical/Jazz Halloween Top Ten on the WRTI site. * New Love Supreme After I mentioned the recently released rediscovered live version of A Love Supreme last month, I thought I should just list some of the reviews: Artforum, The Nation, and the one in The New Yorker by Richard Brody has the following bit about the influence of Ayler on Coltrane: “Coltrane had lately been turning his attention toward what is called, for short, free jazz. He was especially taken with the music of Albert Ayler, a tenor saxophonist who played with an unprecedented, shrieking, roaring fervor. Ayler relied on no harmonic structures, eschewed the foot-tapping beat of most jazz, joined other soloists in raucous collective improvisations, and tapped into the deep roots of Black music—marching bands and gospel sounds—as a springboard for mysterious furies and spiritual explorations. By early 1965, Coltrane’s performances had begun to reveal his affinity for that musical manner.” * Where Rivers Meet Back in May I mentioned an event at St. Giles’ Cathedral in Edinburgh entitled Where Rivers Meet: The Music of Dewey Redman and Albert Ayler, which mixed music and painting, featuring the Scottish National Jazz Orchestra and the artist, Maria Rud. The SNJO have now released an album, via bandcamp, featuring four Suites, devoted to Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler, Dewey Redman and Anthony Braxton. The Ayler Suite includes ‘Ghosts’ (obviously) then ‘Goin’ Home’ and ‘When The Saints Go Marching In’. It’s true Ayler did record the last two on Swing Low Sweet Spiritual, but Albert did like his tunes so it would be nice to rest ‘Ghosts’ for a while and maybe give some of the others a try. There’s a review of the album by Mark McKergow on the London Jazz News site. |

|

|||

|

Bits and Pieces (A phrase inevitably accompanied by the subtle drum patterns of Dave Clark and his Five. I apologise.) Albert Ayler makes an appearance in Rashaad Thomas’s essay, ‘Where I Go: Afropalonia’ on the Zócalo site. He’s also there at the start of this tribute from a Chicago jam session in 1979. Marc Ribot has a book out, Unstrung: Rants and Stories of a Noise Guitarist, which I would guess includes an appearance by Albert Ayler. There’s also a reading from the book and an interview with Marc Ribot on youtube. And the Village Vanguard, where Albert Ayler definitely made an appearance, has reopened after an 18 month closure due to Covid. * And finally ... I was in two minds about this since it has nothing to do with Albert Ayler (no, it’s not the Dave Clark Five) but I came across it on youtube and I thought, I don’t think I’ve ever seen any video of legendary bassist, Scott La Faro. It was posted a couple of years ago, so it’s probably common knowledge, but for those who share my ignorance, here it is:

|

|||

|

December 1 2021

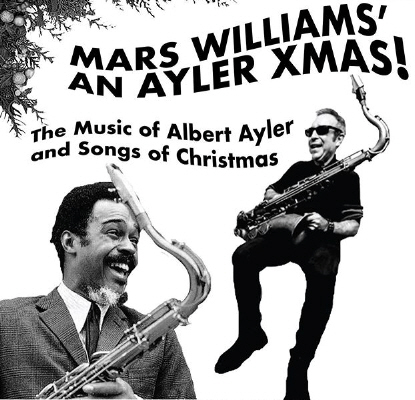

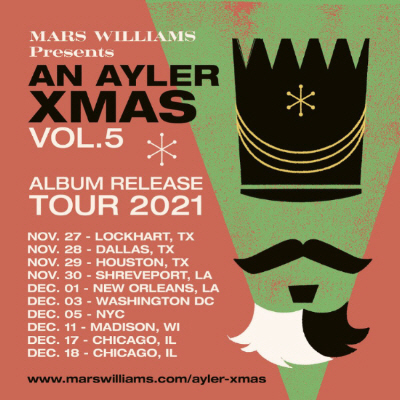

If it’s December it must be time for ... |

|

|

Volume 5 of Mars Williams’ annual mash-up of Ayler tunes with Christmas carols is now available on bandcamp, along with a sample track, ‘The Divine Peacemaker Plays Dreidel In Frightful Weather’ (very appropriate at the moment since we’re in the middle of a cold snap and the scene through the window is very festive, or annoying since I’ve got to go out in a minute). The details are as follows: Mars Williams (Sax, Suona, Toy Instruments), Josh Berman (Cornet), Jim Baker (Piano, Viola, Arp Synth), Brian Sandstrom (Bass, Guitar, Trumpet), Steve Hunt (Drums) Peter Maunu (Violin) Kent Kessler (Bass - Track 1&2) Krzysztof Pabian (Bass - Track 3) Tracks: 1. The Divine Peacemaker Plays Dreidel In Frightful Weather (‘Divine Peacemaker’ and ‘Let It Snow, let It Snow, Let It Snow’). |

|

|

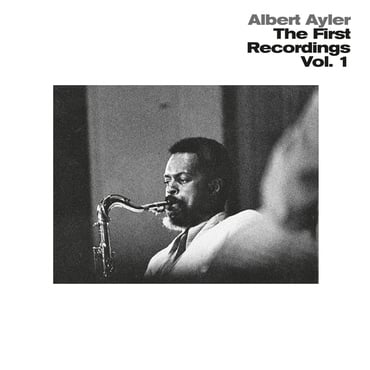

The First Recordings - another one |

|

|

A limited edition (300) vinyl version of The First Recordings Vol. 1. Available from Rough Trade. * I’ve been wondering lately if anyone listens to Albert Ayler anymore. Is the opening line of an article by Richard Cook, published in The Wire in January 1989. I came across it at the Internet Archive where they have a lot of back issues of The Wire. This one also has an interview with Ronald Shannon Jackson. The I. A. also has copies of Coda to borrow (you sign up and then you can access them for a bit but you can’t download them) several of which also contain material about Albert Ayler. Presumably this has been the case for a while now, but I’ve only just discovered if you search for Ayler on the I. A. and click the box marked ‘search text contents’ rather than leaving the default (‘search metadata’) then it brings up a lot of additional material to borrow, including several of the books listed in the Ayler Bibliography. Back to the Richard Cook article. I’ve put it in the Articles section but I thought, since news is short and I’ve already been reduced to talking about the weather, I’d repeat it here:

my name is albert ayler I’VE BEEN wondering lately if anyone listens to Albert Ayler any more. Eighteen years after his death, the man who, more than anyone else, shocked and dishevelled the jazz of his time has become antique. If Ayler came along today, his currency would be, if not exactly commonplace, no more sonically disturbing than many of today’s extremists. AYLER WAS already 27 when his first New York recordings were made. He was born in Cleveland, Ohio in 1936, and like so many of his generation of musicians he served a rhythm and blues apprenticeship. His crucial association in the 50s was with Little Walter’s band: Walter Jacobs played harmonica in a brutal, cleaving style that was not so different from Ayler’s saxophone multiphonics (Albert played alto then, and switched to tenor while in the army in 1958). He built his early reputation in Europe, following his discharge, having found little appreciation in the US for his gathering conception. My Name Is Albert Ayler was recorded in Denmark, a chaotic assemblage of standards and one free piece, culminating in an unholy rendition of “Summertime”. The song becomes an extravagant, blaring music, the saxophone humping up and down over the uncomprehending rhythm players. AYLER’S MUSIC receives its most striking portrayal here, and in the companion records Witches And Devils, Vibrations (alias Ghosts), and The Hilversum Session, the latter two involving Don Cherry as a foil who stands slightly apart from Ayler, offering his own, raised-eyebrow improvisations to the strident sounds around him. “Mothers”, from Vibrations, is a stark dirge which none of Ayler’s critics could take seriously: played remorselessly straight, the saxophonist using a vibrato that shivers like a fevered body, it points towards his next direction. IT’S A long time ago now. Albert Ayler’s death in February 1970 seems to have been at his own hand, his body found floating in the Hudson River. As swiftly as his career ran its course, so did his philosophy move towards the end. “It’s not about notes any more, it’s about feelings,” he said at the beginning. “All my music is purely music of love.” “I really meditate on the universal thoughts, I can’t be restricted to an earthly plane.” “I must communicate with their spirit that comes within the soul and the heart.” “I saw in a vision the new Earth built by God coming out of heaven.” * Lörrach/Paris 1966 Related to the above item (and even more text to read), friend Clive sent me some scans of the 1985 box set of Lörrach/Paris 1966, which included the sleeve notes by Joachim-Ernst Berendt (which were also used in the earlier, 1982 version). I thought I’d transcribe these and have added them to the relevant page in the Discography, but, again, I thought I’d reprint them here: ‘It’s good they are still talking about Coltrane. But there is one tenor player who is just as great as Trane, and he is the other great tenor voice of the sixties, completely independent of Coltrane: Albert Ayler. Joachim-Ernst Berendt There is a similar tone of almost apologetic crusading on behalf of Albert Ayler in both these pieces and I wondered if we’ve gone beyond that now. Perhaps one indication is the appearance of his name among the influences of Celeste, in Variety’s 10 Brits to Watch for 2021. * Two (or three) from youtube First, a brief lecture (in French but subtitles are available) on Marc-Edouard Nabe’s 1989 book, La Marseillaise.

|

|

Next, no ‘Ghosts’ this month, but instead a version of my favourite Ayler tune, ‘Change Has Come’ by El Mantis.

|

|

And finally, evoking the happy family spirit of Christmas, Richard Koloda found this clip of Albert’s grandson, Melvin Fellows, playing American football (sorry Clive).

|

|

I find it impossible to watch American football now without recalling Giles’ line in Buffy: “I just think it's rather odd that a nation that prides itself on its virility should feel compelled to strap on forty pounds of protective gear just in order to play rugby.” * And finally, another Christmas tradition ... Dirk Goedeking’s list of this year’s festive gifts for the Ayler fan. Click the pictures to see them in their full glory, or the links below to go to the sites selling them. |

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Or, as Dirk concludes: |

|

|

|

I reckon that’s Dirk’s house. Merry Christmas, and Omicron willing, see you in 2022. *** December 18 2021 Just a quick update (thanks to Dirk Goedeking): There’s a live stream of Mars Williams’ ‘An Ayler Xmas’ concert from Chicago on youtube tonight, Saturday 18th December at 8.30 pm (which, fo those over here in the UK, is tomorrow, 19th December, 2.30 am), |

|

*** News from 2004 (January - June) 2004 (July - December) 2005 (January - May) 2005 (June - December) 2010 (January - June) 2010 (July - December) 2011 (January - May) 2011 (June - September) 2011 (October - December) 2012 (January - May) 2012 (June - December) 2013 (January - June) 2013 (July - September) 2013 (October - December) 2014 (January - June) 2014 (July - December) 2015 (January - May) 2015 (June - August) 2015 (September - December) 2016 (January - March) 2016 (April - June) 2016 (July - August) 2016 (September - December) 2017 (January - May) 2017 (June - September) 2017 (October - December) 2018 (January - May) 2018 (June - September) 2018 (October - December) 2019 (January - May) 2019 (June - September) 2019 (October - December) 2020 (January - April) 2020 (May - August) 2020 (September - December) 2021 (January - March) 2021 (April - July) 2022 (January - April) 2022 (May - August) 2022 (September - December) 2023 (January - March) 2023 (April - June) 2023 (July - September) 2023 (October - December) 2024 (January - March) 2024 (April - June) 2024 (July - September) 2024 (October - December)

|

|

Home Biography Discography The Music Archives Links What’s New Site Search

|