|

Music Is The Healing Force Of The Universe The Inconsistency of |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

October 1 2017

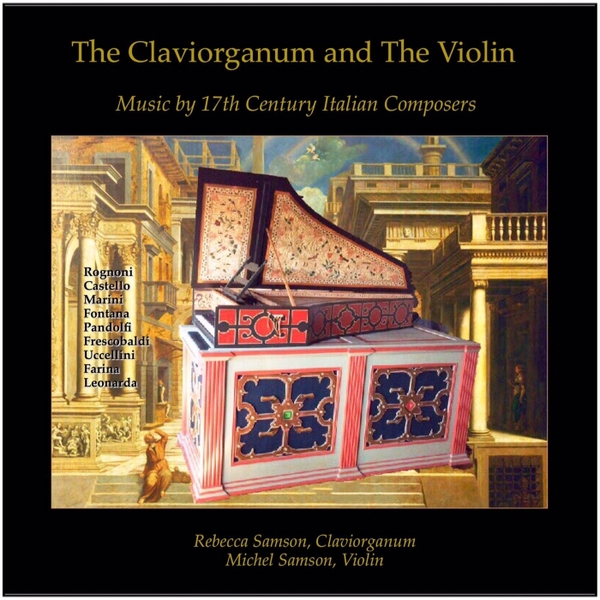

The Claviorganum and the Violin Usually we don’t get much further back than the 1960s, so it makes a nice change to spend some time in the 17th century. |

|

||||||

|

This (as it says on the cover) is a CD of music from 17th century Italian composers, played by Michel Samson on the violin and his wife, Rebecca, on the claviorganum. And I make no excuses for mentioning it here, especially since I’d never even heard of a claviorganum (a cross between a harpsichord and an organ) until Dirk Goedeking sent me this link. And if you want to know what else Michel Samson is getting up to these days there’s his wife’s blog, The Expat Epicure. And here’s the duo in action:

|

||||||

|

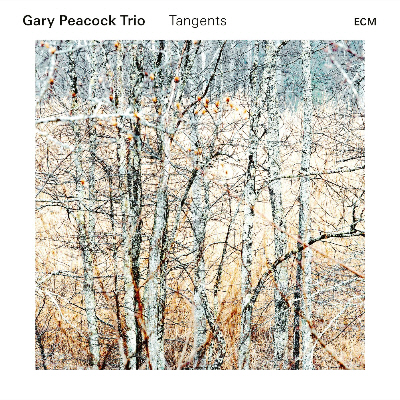

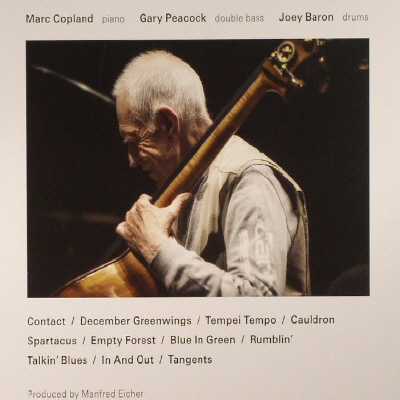

Gary Peacock Dirk also sent me a link to the January 2017 edition of The Online Journal of Bass Research which has an 8 part article about Gary Peacock’s contribution to the first track of Spiritual Unity: ‘Revolution in Action: A Motivic Analysis of “Ghosts: First Variation” As performed by Gary Peacock’ by Robert Sabin, Ph.D. This is a very detailed and serious academic study, which includes transcriptions of the music. Robert Sabin is also a composer and a bass player (he studied with Gary Peacock and the latter was the subject of his Ph.D. thesis) and more information about him and his music is available on his own website. And, on the man himself, there’s a review of his latest trio CD, Tangents, on the popMATTERS site. |

||||||

|

|

|||||

|

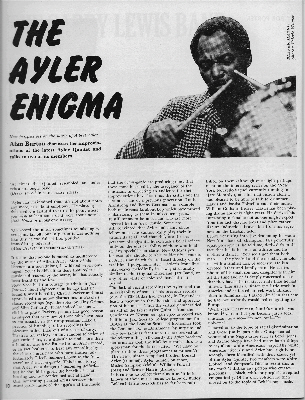

Beaver Harris, Bill Folwell and the L.S.E. again Back in the day, I subscribed to Jazz Monthly so missed this article by Alan Barton in the February, 1967 edition of Jazz Journal, but that’s what ebay’s for. The article includes a brief interview with Beaver Harris (and Bill Folwell gets a walk-on part) and it was written around the time of the L.S.E. concert in the previous November. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

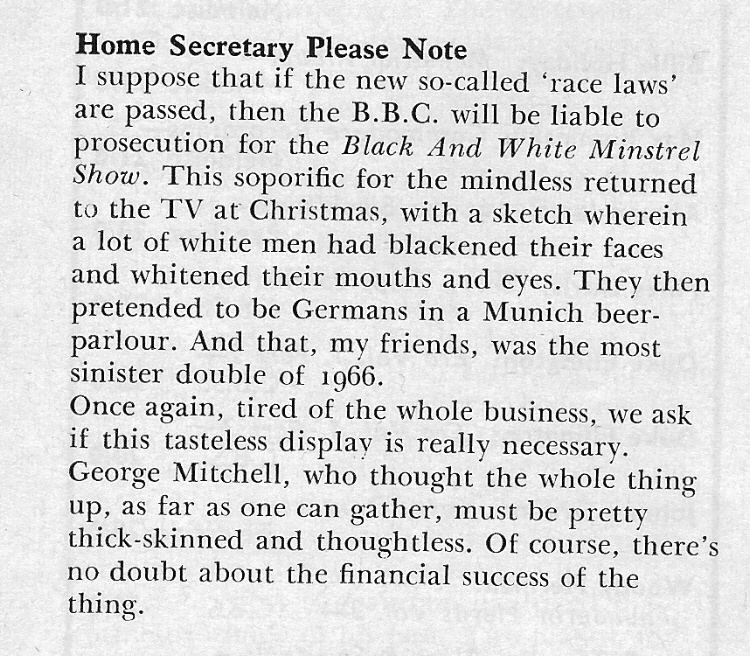

I also came across this on Steve Voce’s ‘It Don’t Mean A Thing’ page, which I thought I’d share: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Unfortunately the Home Secretary was a Jazz Monthly subscriber and the BBC continued to broadcast the Black and White Minstrel Show until 1978. And finally, one of the delights of old British jazz magazines is the Letters Page. * Creative Healing I came across an advert for an old concert in Washington DC, by a Boston group called Creative Healing, which had the following blurb: ‘The spiritual and avant-garde jazz pioneer Albert Ayler liked to say “Music is the healing force of the universe.” He liked it so much, in fact, that he used the phrase to title one of his last albums. Ayler, a tenor saxophonist and band leader, wrote creative pieces of deceptive complexity and cacophony. While his band created quite a sound when it played, the melodies he wrote were crafted in the spirit of front-porch folk songs, inviting every listener in to hum along and feel the force of the music in the room. Creative Healing, a five-piece made up of rising voices in Boston’s creative music scene, tries to fulfill Ayler’s vision. In a mix of free form jazz improvisation, noise rock force, and spoken prose, Creative Healing aims to create music that unites audiences in heart and mind. The music may sound discordant and harsh, but just breathe and let it in. You can find the harmony and beauty if you just listen.’ And here they are on youtube:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

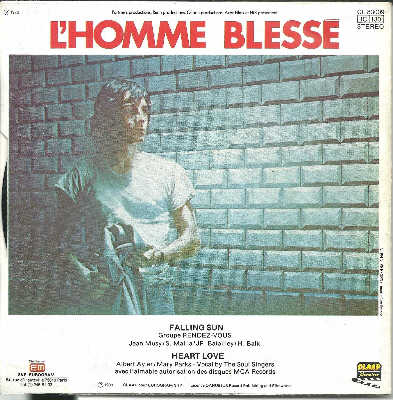

And another thing I came across This is from Point of Departure No. 25, from way back in October, 2009. No idea why it’s not popped up before (although maybe it has) but, yet again the L.S.E. concert gets another mention. This is an extract from a round table discussion between Chris Kelsey, Bill Smith (of the Canadian Coda magazine) and Dan Warburton, moderated by Bill Shoemaker. This is a bit of Bill Smith’s contribution: ‘Shoemaker: Journalism idealizes objectivity; yet so much journalism and criticism about jazz and other forms of experimental is agenda-ridden; the writer has a cause he or she wants to advance through their writing. Bill’s desire to “make the music go forward” encapsulates this well. The problem is that the way ahead shifts over the years. Certainly, the horizon in front of me when I first started writing about music in the late ‘70s is now but a dot in the rear-view mirror. How have your agendas changed over the years, and how are they reflected in both your music and your writing? Smith: In the latter half of the sixties when I initially imagined a future in music, my living was made firstly in engineering as a draughtsman and then as a photographer for a city magazine, so jazz music was little more than a delightful hobby. Although I had already formed serious opinions regarding the “new” music of Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor – my two favorite pioneers, I was never altogether enamored by John Coltrane, who had already achieved fame with Miles Davis and his own quartets; his music not seeming to be a radical departure. Once again it’s because of Coda Magazine that I progress to the next stage of American history. Physically assembling the magazine was a social gathering of friends around a table with piles of pages and staple guns. John Norris had an enormous record collection covering two walls of his apartment, and one of the compensations for our work was to choose a recording from his vast selection. Stuart Broomer, at that time a rather precocious young man, chose one of Albert Ayler’s ESP recordings. Two weeks later I headed for New York City to investigate this amazing music. Fortunately he was appearing everywhere: The Astor Playhouse, Slugs, The Dom, and the Lincoln Center as a guest of John Coltrane at the “The Titans of the Tenor” concert. He would become my standard bearer. There was obviously no looking back. By the end of that decade I had returned to England on an engineering contract and while there again came in contact with Albert’s music; a BBC-TV recording (that was erased and never shown) – which I reviewed in the Melody Maker. On the same journey I hung out with Chris McGregor and the expatriated South Africans in London, and Jeanne Lee, Ran Blake and Don Cherry in Paris. The very same Beuscher tenor saxophone accompanied me on this journey and I was very fortunate to receive casual lessons from Ronnie Beer. A most auspicious entry into the world of the “avant garde”. Here, forty-odd years on, Albert Ayler is still my guiding light, a joyous ritual in which to regularly luxuriate, my constant connection with the unfolding history that I’ve been privileged to witness. Of course along the way there have been numerous discoveries and musical influences, the likes of Anthony Braxton, Leo Smith, Roscoe Mitchell, Joe McPhee, Evan Parker, Paul Rutherford, the Spontaneous Music Ensemble… the list go on.’ * L’Homme Blessé Last month I put the trailer from L’Homme Blessé on this page, courtesy of Dirk Goedeking. What I forgot to do was add the covers of the soundtrack single, featuring Ayler’s ‘Heart Love’ which Dirk also sent, with the following note: ‘“Heart Love” is coupled with “Falling Sun” by Rendez-Vous, a 1979 disco number. ... This is Albert’s 6th 7 inch (besides 1. Holy Family/Sadness, 2. Ghosts/Love Flower/Zion Hill, 3. Free At Last/New Ghosts, 4. New Generation /Heart Love and the single sided 5. The Lie). So if you own a jukebox, ...’ |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

And on youtube . . . If you want to know what ‘avant-garde’ means, there’s a cartoon lady explaining it and mispronouncing Albert Ayler. If you want a good example, there’s a 2014 concert from Joe McPhee’s Universal Indians. And then there are a couple of versions: 1. ‘Truth Is Marching In’ by the Ensemble of Irreproducible Outcomes.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

2. Inevitably, ‘Ghosts’, but since we began in 17th century Italy, it seems fitting to end this month in 16th century England with John Dowland - both performed by Four Letter Words.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

What’s New June - September 2017 is now in the Archives. *** November 1 2017

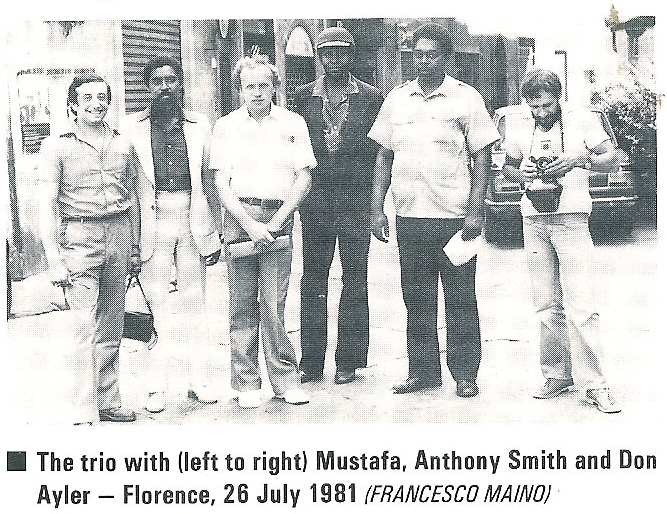

Mustafa Abdul Rahim Roy Morris informed me of the recent death of Mustafa Abdul Rahim, a childhood friend of the Ayler brothers. I’ve not been able to find anything online about his death, and very little about his career, so I apologise for the paucity of this obituary. He started out as Donald Strickland, went to school with Don Ayler in Cleveland, and is mentioned by Val Wilmer as being inspired by Albert Ayler (after his return from Scandinavia) to imitate his style. He played bass clarinet as well as saxophones and there’s a mention of him on the organissimo jazz forum: “I spent an afternoon with [Charles] Tyler while in New York back in 1967 when he was rehearsing a group that included Majid Chabazz on drums and an incredibly talented bass clarinet player by the name of Donald Strickland. I’ll come back to that later. There’s another mention of Strickland in a Coda review by Elisabeth van der Mei from November 1968, following the split between Albert and Don: “Don is forming his own group at the moment, which includes Noah Howard, alto; and Donald Strickland, bass clarinet. Haven’t heard them yet, but hope to soon.” So much for Donald Strickland. As Mustafa Abdul Rahim, he joined the Master Brotherhood, which also featured Joe Rigby: “The Master Brotherhood was a fantastic group of young musicians. We played a lot of Brooklyn gigs. We all got along very well with no ego trips. One of the group that didn’t record with us, but was an important member was bass clarinetist Mustafa Abdul Rahim.” After the split with Albert, Don Ayler returned to Cleveland and, as we know, found it hard to deal with what had happened in New York and the subsequent death of his brother. Mustafa Abdul Rahim was one of the people (along with Al Rollins) who helped Don start playing again and in 1981 he was part of the group that went to Italy and recorded the 3 LP set, Don Ayler In Florence 1981. Here’s a photo of three members of that group with the Ganelin Trio: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

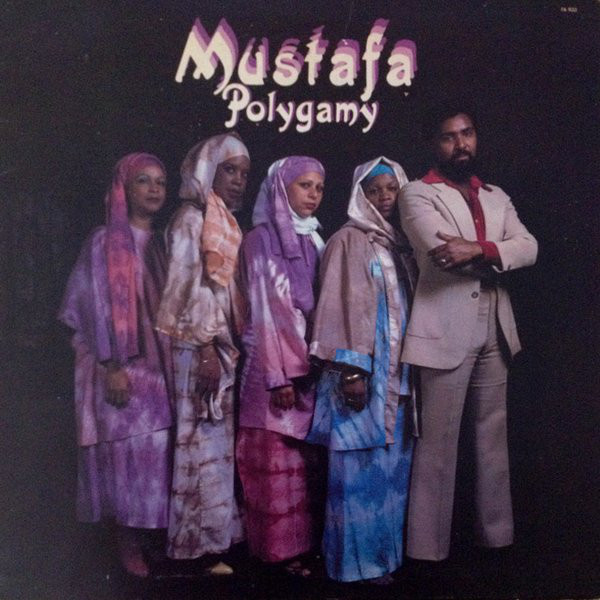

So that was one recording, although he was credited as Abdul Rahim Mustafa. However, two years before the trip to Florence, there was another LP released on the Fatimah Records label, this time under the name Mustafa Abdul Rahman, with the title Polygamy. The name-changes are confusing, but I think I’ve got this right, and the presence of two musicians from the subsequent Florence LPs - Tony Smith, piano and Richard ‘Radu’ Williams, bass - does seem to confirm it. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There are a couple of tracks on youtube, the title track:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

And ‘Silent World’ written by Tony Smith and Ayisha Khalil:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

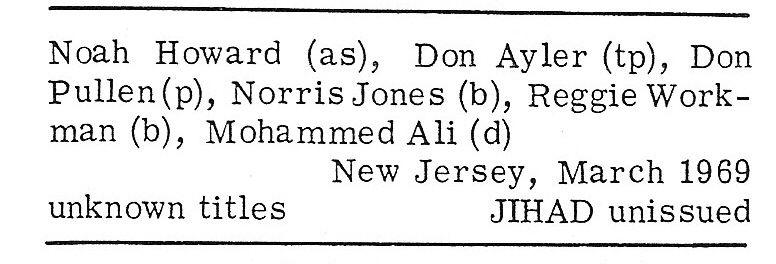

And the whole album is available to download here. * Noah Howard Roy also sent me an interview with Noah Howard from the April, 1976 edition of Coda. It’s available below in full, but here’s the section relating to Albert Ayler: “Roberto Terlizzi: What kind of relationship did you have with Albert Ayler? Noah Howard: Albert and I were very close as men as well as artists. He understood me as a person, as a young artist moving ahead to do something; he recognized this in me. I greatly appreciated his gift to music, he was a very great artist. It was a very strange thing between me, Albert and Coltrane. Albert was as close to me as John was to him, there would be days he’d talk to Coltrane on the telephone and, say, three hours later he’d talk to me. R. T.: Did he ever talk to you about the irony in his music, if there was any? N. H.: I would say no, of course I may give you my interpretation, you can have yours, but we are not in the mind of the artist, so he knew what he was doing, the only thing I can do is being a receiver and enjoy it, enjoy the gifts he gave to the world. I’ve heard of other artists that have done the same kind of thing, like the American composer Charles Ives, who took contemporary folk themes and built a whole improvisational structure on them. The same we may say of Trane playing My Favourite Things or Chim Chim Cheree. Only the artist knows what he is trying to do.” The other item of specific Ayler-interest is in the attached Noah Howard discography, which contains this item: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This confirms the personnel details of the infamous unreleased Don Ayler LP on Amiri Baraka’s Jihad label (unsurprisingly since they came from the same source - a Noah Howard interview in the April 1976 edition of the French magazine, Jazz Hot), but it adds a tentative recording venue and date, which places it only two months after that coruscating Town Hall concert in January, thankfully preserved in the Holy Ghost box. Anyway, here’s the Noah Howard interview: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

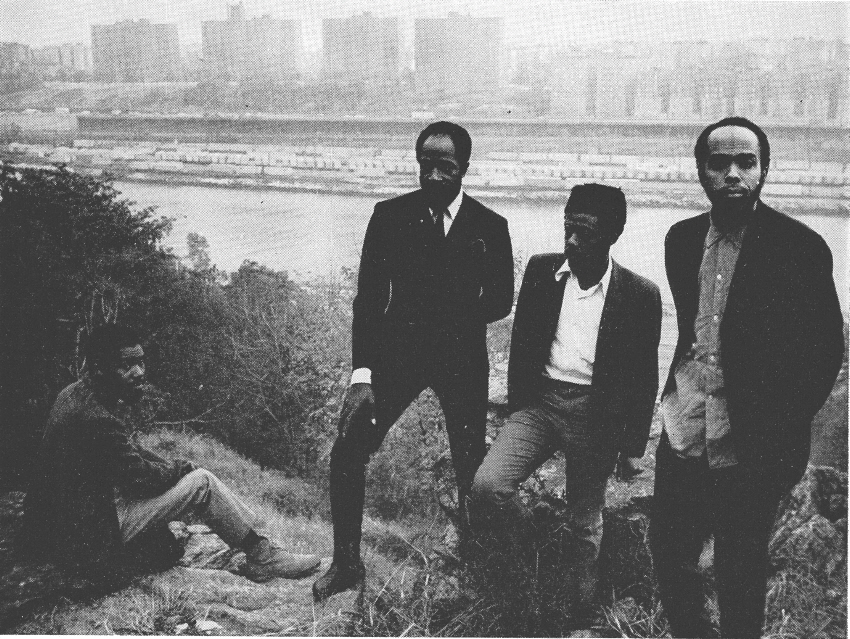

Roy also sent me an interview with Amiri Baraka (conducted by David Keenan) from the January 2001 issue of The Wire which begins: ‘November 1965: In the wake of the withdrawal of funding from poet, publisher and black activist LeRoi Jones’s Black Arts Repertory Theatre in New York’s Harlem district, militant freedom drummer Sunny Murray calls a machine-gun studio summit, boldly proclaiming it Sonny’s Time Now. All the young bloods heed the call — saxophonist Albert Ayler, trumpeter Don Cherry, bassists Henry Grimes and Louis Worrell, and Jones himself regroup for a magical war council, a séance where they seek to bring down upon themselves mastery of the Blackest Arts and so raise the skies of America with the stream of their music. As Murray dynamites his snare drum, and Ayler and Cherry fire off rounds of weeping bullets, Jones sets the charges. “We want poems that kill,” he trumpets. “Poems that shoot guns. Poems that wrestle cops into alleys and take their weapons leaving them dead with tongues pulled out and sent to Ireland!”’ Which contrasts rather with the account in the March 1969 issue of Jazz Monthly of an anonymous friend of Don Cherry’s: “As you said in your review, there is some fine jazz on the album. This is a great pity in some ways, for reasons that will become clear below. I’ve had the Jihad disc for what seems like a long time and my feelings about the LeRoi Jones ‘poem’ are similar to yours. One day when Don Cherry was at my place I asked him about the session because I couldn’t understand how in hell he or Albert Ayler got to be associated with that stuff. Don’s only positive remark was, ‘Wow, Sonny’s got a record out!’ The rest was obviously hurting him. It seems there was a wild party—probably Xmas or New Year—at which pretty well everyone got drunk. LeRoi Jones took advantage of the situation, got a cab and shuffled horn men over the east side to the Black Arts Theatre or some place like that. The rhythm men were, I gather, awaiting their arrival, much to Don’s and Albert’s surprise. They were assured that this was a private session, but couldn’t help noticing the set-up of recording gear. . . . it was some kind of dunky studio. All this appears to have been strictly LeRoi Jones’s deal for the Black Arts Rep. Don Cherry has no clear recollection of what, if anything was played at the session, by which I mean he didn’t recognise the material when the disc was played. About all he could say was that it sounded pretty definitely that he was on that session, and he didn’t dig the idea one little bit.” You pays your money ... etc. Later in the interview there’s this: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

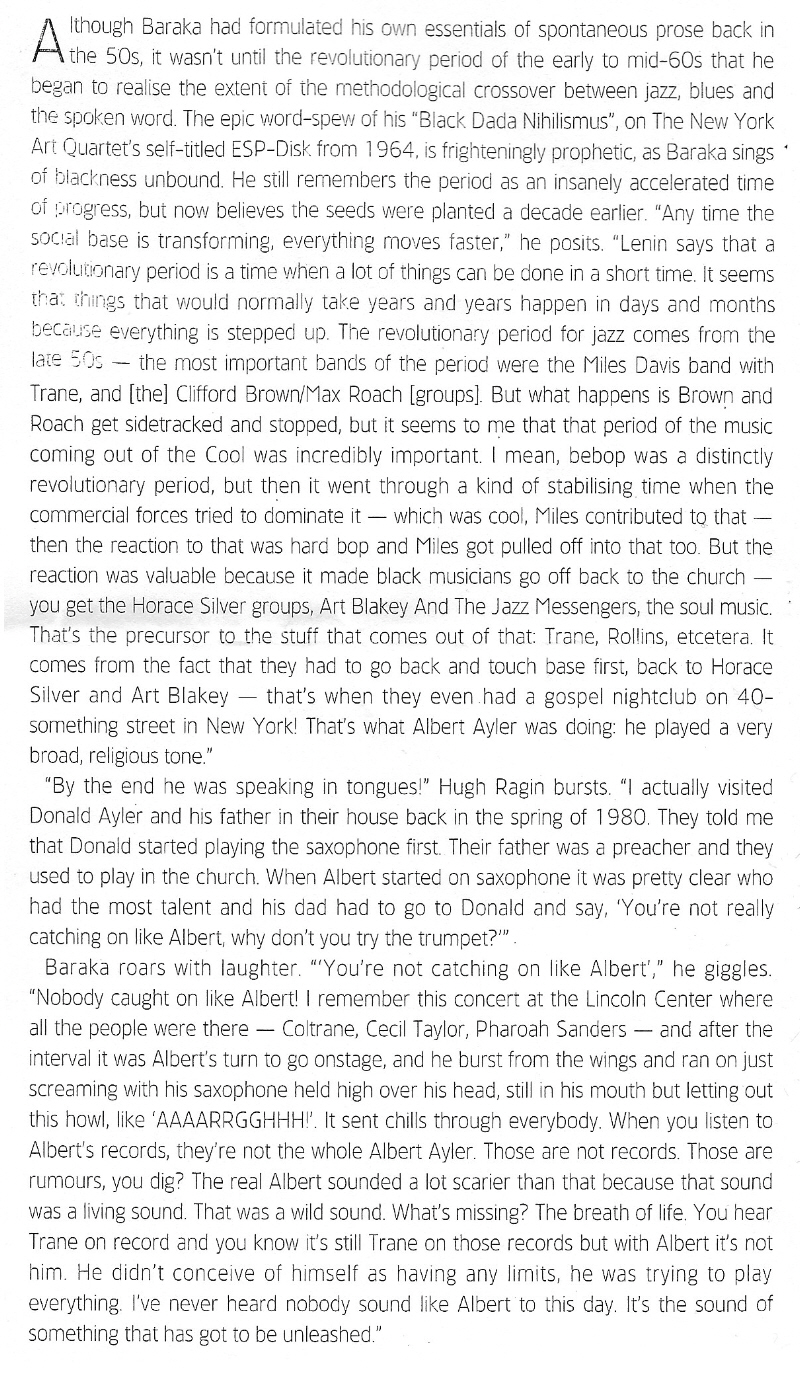

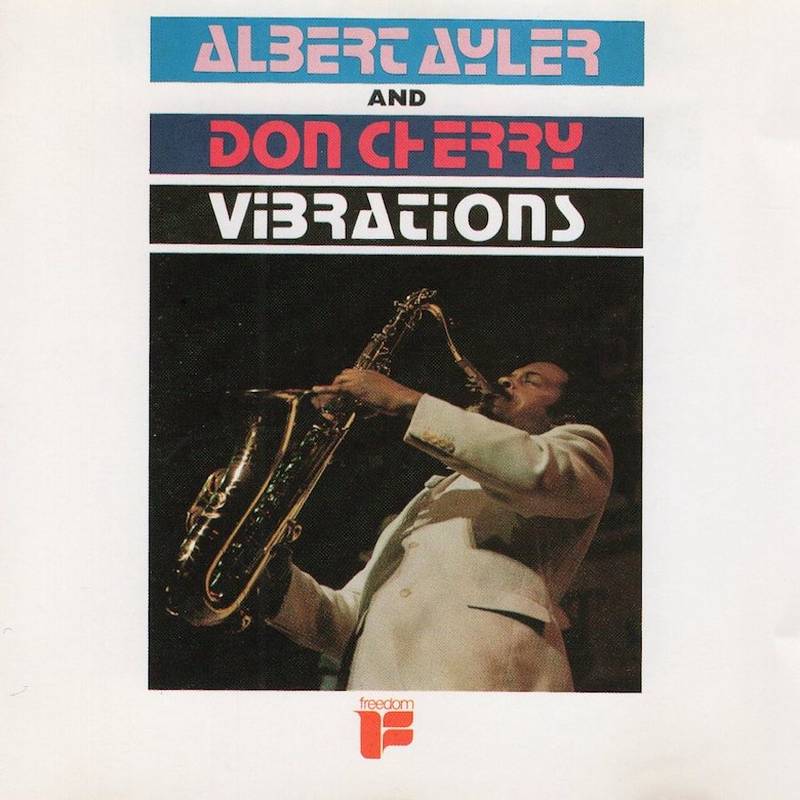

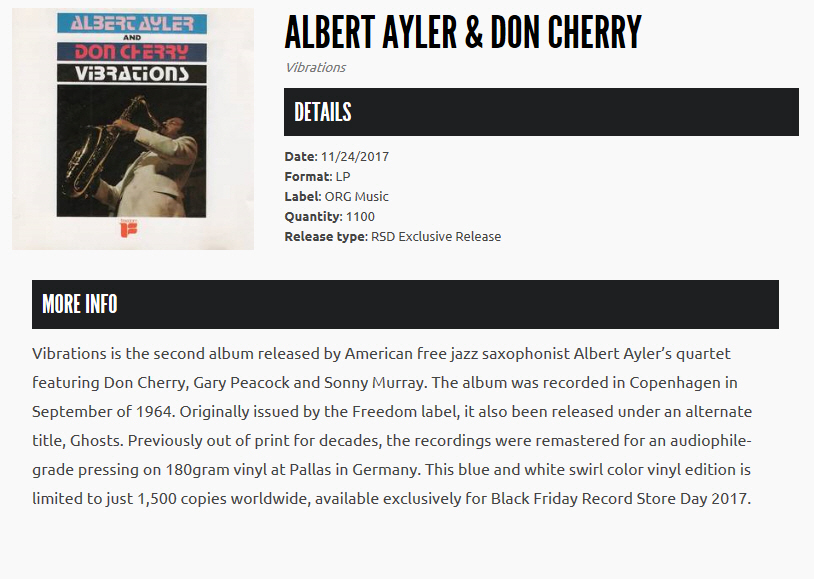

So, many thanks to Roy Morris, and if you want more information about Noah Howard, there’s another interview (this one from 2006) on the website of The Wire. * Creative Marketing or Sacrilege? ESP are issuing a new vinyl edition of Bells, but Bells with a difference - this time the B-side is not going to be blank - instead it will have the ‘alternate take’ of ‘Spirits’ which appeared on the early pressings of Spiritual Unity. I don’t think it matters really, and there’ll be another vinyl version for Mats Gustaffson to add to his collection. * Record Store Day As part of Record Store Day on Black Friday, 24th November, 2017, there will be an exclusive vinyl release of Vibrations (aka Ghosts). ORG Music is producing 1100 copies of the LP which is described as follows: “Vibrations is the second album released by American free jazz saxophonist Albert Ayler's quartet featuring Don Cherry, Gary Peacock and Sonny Murray recorded in Copenhagen in 1964. Having been out of press for decades, the recording will be remastered for an audiophile-grade pressing on 180gram color vinyl at Pallas in Germany.” |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

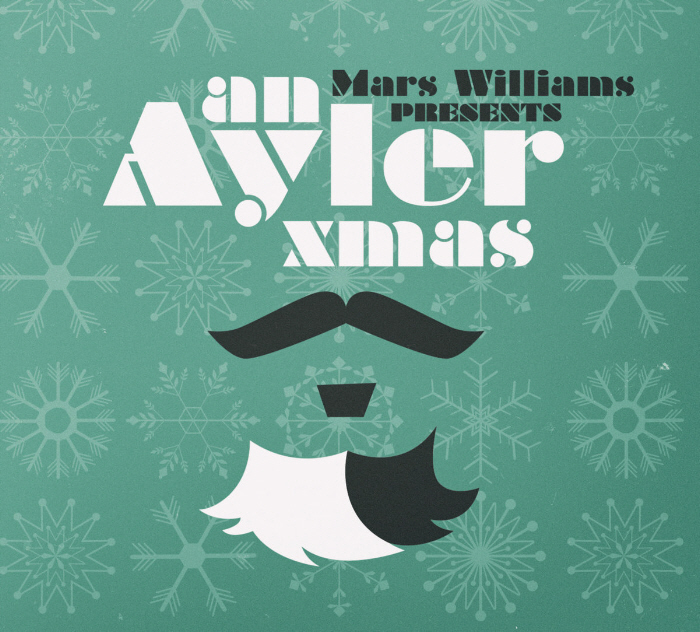

An Ayler Xmas I’m usually late with this news, but Richard Rees-Jones let me know that the Mars Williams version of Christmas carols with an Aylerish bent will be peformed at the Bimhuis in Amsterdam on Saturday 23rd December, 2017. There’s also a possibility that the concert will be broadcast on the Bimhuis website’s radio station. * Life-changing jazz albums: 'Spiritual Unity' by the Albert Ayler Trio This is an article on the jazzwise magazine site by saxophonist Shabaka Hutchings about the effect Spiritual Unity had on his own approach to music. * Youtube roundup First, one that I missed earlier but Dirk Goedeking spotted, ‘Omega is the Alpha’ played by the Spoilers of Utopia from 2012:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Then three fairly hefty items: Marc Ribot’s Spiritual Unity (Live in France and Austria, 2005) Ensemble of Irreproducible Outcomes at Bop Shop Records Rashied Ali & Henry Grimes interviewed by Monk Rowe - 31st January, 2009 And finally ... Because Who Doesn't Like Free Jazz?

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

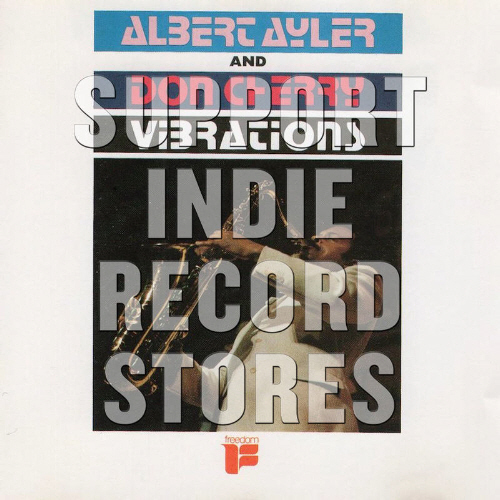

December 1 2017

Mustafa Abdul Rahim - continued Following last month’s piece about the death of Mustafa Abdul Rahim (fka Donald Strickland), I was contacted by Guy Kopelowicz, saying that he was the contributor to the organissimo forum who’d mentioned meeting a “talented bass clarinet player by the name of Donald Strickland” in New York in 1967. Guy kindly sent me a copy of the article he subsequently wrote about Charles Tyler’s group for the French magazine, Jazz Hot. In the group photo which introduces the piece, Donald Strickland/Mustafa Abdul Rahim is seated on the left. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The article is available below: Jazz Hot (January, 1968 - pp.19-22): |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Vinyl News Steve Holtje of ESP sent me a photo of his kitchen table on which were the new repressings of New York Eye And Ear Control on white vinyl and Bells with a B-side (of the alternate take of ‘Spirits’ from the original copies of Spiritual Unity - mentioned last month). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

And here’s the cover, and the blurb accompanying the release of Albert Ayler’s Vibrations (aka Ghosts) for Record Store Day: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Film News 1 - Bobby Few Pierre Crépon emailed to say he’d seen the new French documentary film devoted to Bobby Few, who played piano on Albert Ayler’s last two Impulse albums. Bobby Few: Musical Hurricane was directed by Nicolas Barachin and although Pierre says it adds nothing new about Ayler, there is a sequence where Bobby Few sings ‘A Man Is Like A Tree’ while standing next to a tree:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

After the film was shown, Pierre says there was a Q & A session with Bobby Few in which he revealed he was also featured in a Heineken advert shot in Hong Kong. Pierre liked the incongruity of an Ayler sideman appearing in such a context, although I don’t think it beats Bill Folwell appearing in a Charles Bronson film. * Film News 2 - Lee Morgan, John Coltrane and Oscar Isaac The second series of Stranger Things appeared on Netflix at the end of October, so I signed up again and also took the time to watch Kasper Collin’s I Called Him Morgan. It’s very similar to My Name Is Albert Ayler, although there is probably more of a narrative hook revolving around Lee Morgan’s eventual fate. The style - photos, short performance film clips, interviews with survivors, linking shots of atmospheric cityscapes - is the same, and it is a very fine piece of work. Netflix also has the John Coltrane documentary, Chasing Trane, directed by John Scheinfeld. This is similar to the work of Kasper Collin, although, given the subject, there’s more of a, well let’s say, polished, feel to the piece. Coltrane’s words are spoken by Denzel Washington and President Bill Clinton is one of the talking heads. Coltrane’s story, of course, lacks the mystery surrounding Ayler’s death and the pulp fiction plot of Lee Morgan’s, so it is more of a straightforward documentary. Ayler, of course, is not mentioned, but he does appear in one of the photos taken outside St Paul’s Lutheran Church on the occasion of John Coltrane’s funeral. And, I’ll stick this in here. I came across a short film starring Oscar Isaac on vimeo. It’s called Lightningface and was directed by Brian Petsos, and I mention it here because it uses Don Ayler’s ‘Our Prayer’ at the film’s conclusion and over the end credits. * Albert Ayler in The Tatler Apologies for the rather random collection of items this month, but it is the last update of the year. These are a couple of things I found on the British Library Newspaper Archive site. The first is an odd article from London Life (formerly The Tatler) from 4th June, 1966, about the current state of jazz. It seems to have prompted by the release of some ESP albums, but the writer of the article, Hugh Blackwell, does not seem that happy with the way jazz is going, and sees Ravi Shankar as a better bet for the future. As well as the description of the ‘psychedelic anti-music’ of Sun Ra and his Solar Arkestra (“10 bald Negroes who dress in luminous ceremonial robes for personal appearances, sit in a circle in total darkness except for the glow off their clothes”) there is this critique of Albert Ayler: “Albert Ayler, a tenor saxophonist, is best known of the New Thing noisemakers. Melody Maker has been busy controverting about him for months. Musically he is way out on a limb, neither protesting, dissenting, prophesying nor even really contributing creatively.” The article is accompanied, for no apparent reason, by a photograph of popular beat combo, The Move. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

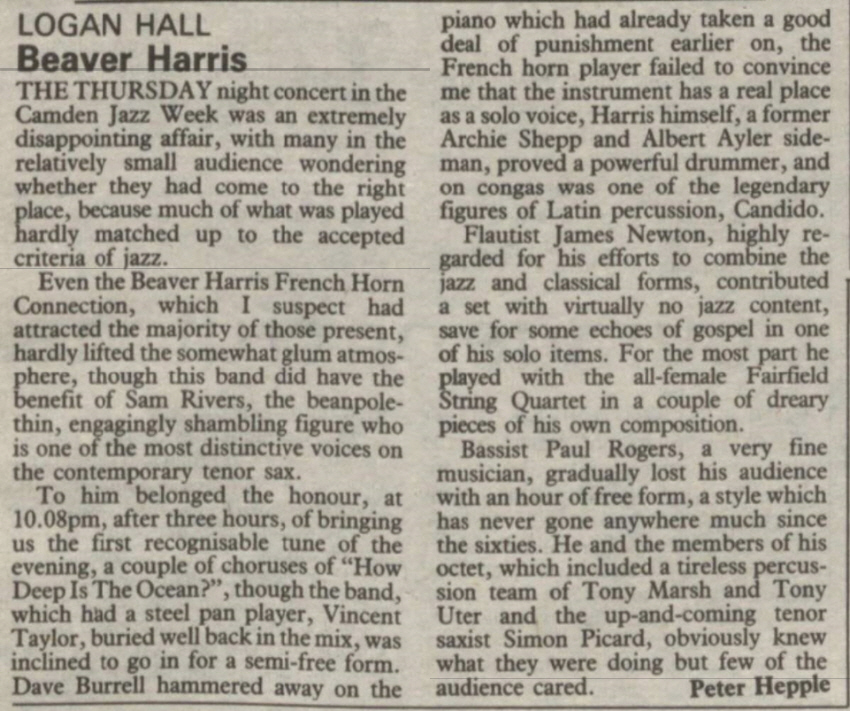

The second item is a review of a Beaver Harris concert from The Stage of 28th March 1985, showing, if nothing else, that the intervening 20 years had done nothing to cheer up British jazz journalists. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Enlightened Parenting ... ... or a case of child cruelty, or perhaps we are witness to the birth of a future British jazz journalist; although this is France. Franck Médioni, editor of Albert Ayler: témoignages sur un Holy Ghost published in 2012, has a series of videos - La Jazzbox - on vimeo, filmed at the bookshop, La Manœuvre, in Paris. This is the one about Albert Ayler.

Franck Médioni - La Jazzbox : Albert Ayler from remue.net on Vimeo. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Christmas First off, following the mention of Mars Williams’ Ayler Christmas concert on Saturday 23rd December at the Bimhuis in Amsterdam (and by the way, Kees Hazevoet emailed to say there’s also one in Holyoke, Massachusetts on December 1st - full tour details here), Dirk Goedeking let me know that there’s a Mars Williams Ayler Christmas CD, which can be sampled on the bandcamp site. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

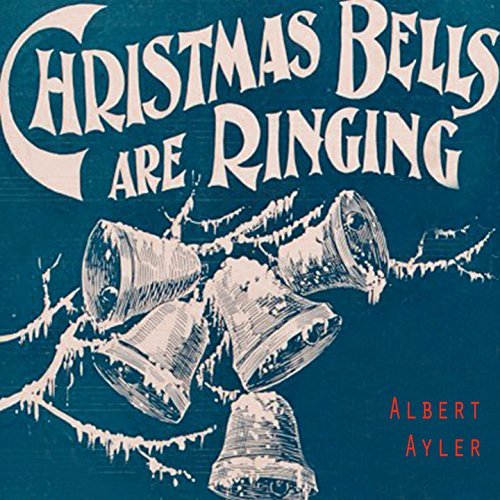

So, click the link and listen to the mingling of Albert Ayler with the Red Flag, while we run through Dirk’s list of Christmas gifts for the Ayler fan who has everything: 1. Another Lost Ayler Christmas Album: This is available from the Japanese amazon and seems to share its track list with My Name Is Albert Ayler. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

2. Albert Ayler Trio - Spiritual Unity 1964 Free Jazz - acrylic block (2 sizes): |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

3. Duvet Cover: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

4. T-shirts with randomly selected saxophonists names on them: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

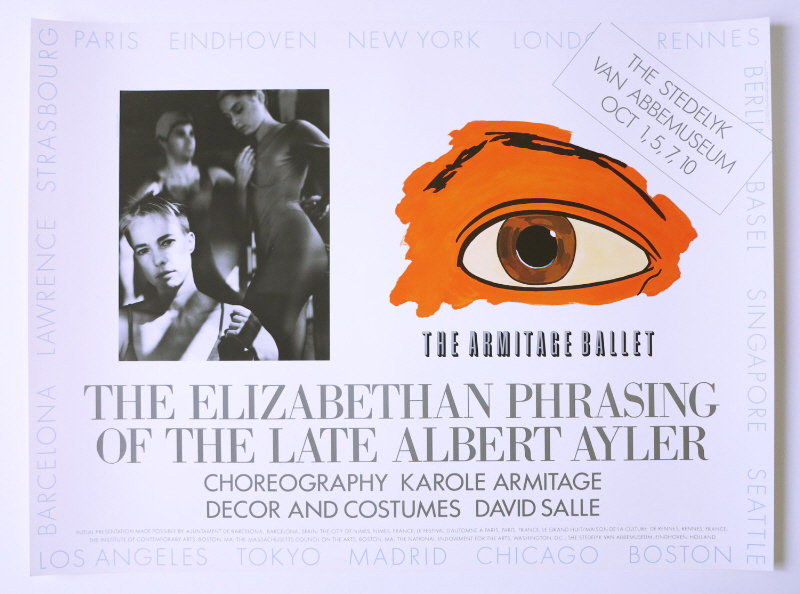

Although that site did turn up an old favourite, an original poster for ‘The Elizabethan Phrasing Of The Late Albert Ayler’: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

5. A Mug: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

6. Cards: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

7. A Yoga Mat: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In fact, pretty much anything. Although I think Dirk was stretching it a bit with this bottle of beer. Still there is one quality item on the list (apart from the poster for ‘The Elizabethan Phrasing Of The Late Albert Ayler’) a sculpture by Arman (Armand Fernandez, 1928-2005) - ‘Albert Ayler Memorial 1974’ - consisting of a sliced saxophone in concrete (auction estimate 60,000 - 80,000 euros): |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

So, that’s about it for another year. Still, what the hell, it’s nearly Christmas, so here’s yet another version of ‘Ghosts’, this time by Phillip Johnston & the Coolerators:

Ghosts (Ayler) - Phillip Johnston & the Coolerators from Phillip Johnston on Vimeo. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

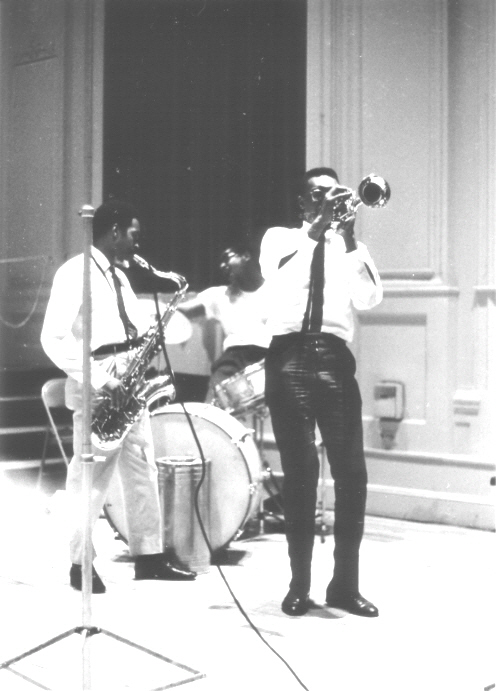

Sunny Murray (21/9/1936 - 8/12/2017) Sad to report the death of Sunny Murray at the age of 81. He played drums on several iconic Ayler albums, from Spirits (recorded in February, 1964), through Spiritual Unity, New York Eye and Ear Control, Ghosts, The Hilversum Session, Bells, Spirits Rejoice to Sonny’s Time Now (recorded in November, 1965). Of course, he was more than just a sideman, he was undoubtedly the premier drummer of the free jazz movement in the 1960s and he leaves an impressive body of recorded work. It’s early yet for the full obituaries, but there are mentions on Pitchfork, Liberation and Spin. Thanks to Pierre Crépon and Kees Hazevoet for letting me know, and here’s one of Guy Kopelowicz’s photos of Sunny Murray with the Ayler brothers at the Spirits Rejoice session: |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

*** News from 2004 (January - June) 2004 (July - December) 2005 (January - May) 2005 (June - December) 2010 (January - June) 2010 (July - December) 2011 (January - May) 2011 (June - September) 2011 (October - December) 2012 (January - May) 2012 (June - December) 2013 (January - June) 2013 (July - September) 2013 (October - December) 2014 (January - June) 2014 (July - December) 2015 (January - May) 2015 (June - August) 2015 (September - December) 2016 (January - March) 2016 (April - June) 2016 (July - August) 2016 (September - December) 2017 (January - May) 2017 (June - September) 2018 (January - May) 2018 (June - September) 2018 (October - December) 2019 (January - May) 2019 (June - September) 2019 (October - December) 2020 (January - April) 2020 (May - August) 2020 (September - December) 2021 (January - March) 2021 (April - July) 2021 (August - December) 2022 (January - April) 2022 (May - August) 2022 (September - December) 2023 (January - March) 2023 (April - June) 2023 (July - September) 2023 (October - December) 2024 (January - March) 2024 (April - June) 2024 (July - September) 2024 (October - December)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Home Biography Discography The Music Archives Links What’s New Site Search

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||